What’s dragging down Illinois’ economy?

Illinois would have seen above-average growth if the state’s workforce had simply grown on par with the rest of the U.S. economy. Instead, poor policy choices have made the state an economic laggard. Illinois’ slow expansion is likely a product of investment-killing tax hikes.

Illinois is home to a well-documented people problem. The state’s population has been shrinking for four consecutive years, and its labor force is declining as well. At the same time, Illinois’ economy is lagging the nation in terms of growth.

Analyzing the component parts of economic growth shows how these two unfortunate realities are connected. And how state and local tax hikes in Illinois are making things worse.

Illinois’ slow growth

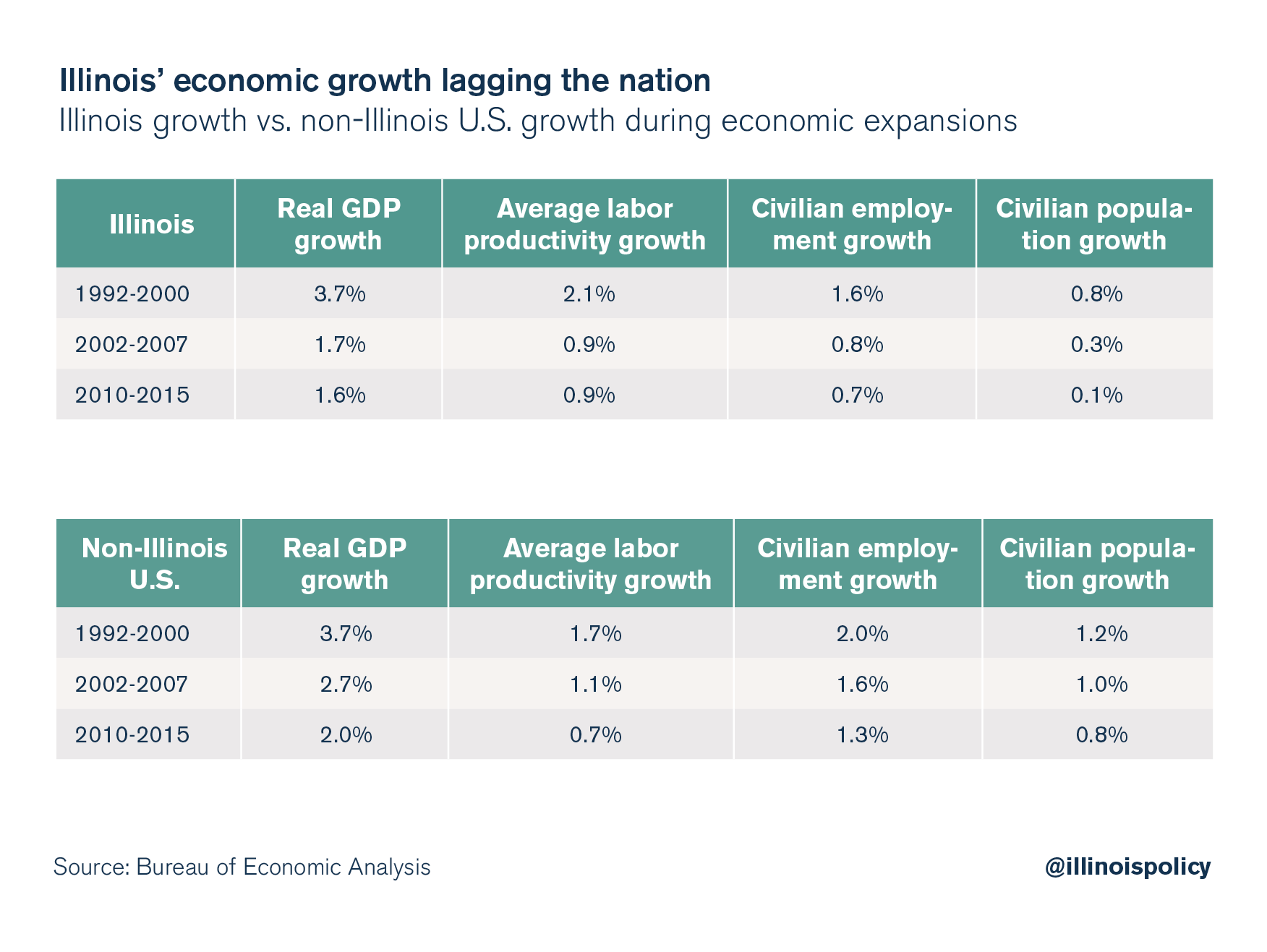

Analyzing economic growth in Illinois requires deconstructing the state’s growth in real gross domestic product into its primary contributions: labor inputs and labor productivity. The production process transforms labor, capital and technology into output (real GDP). That means if Illinoisans work fewer hours, or more Illinoisans leave the state or retire earlier over time, labor input in the production process will grow more slowly or even shrink. Declining labor input can easily cancel out any improvement in productivity growth, leaving real GDP growth unchanged or even lower than before.

Labor productivity growth and employment growth declined in Illinois relative to other U.S. states. These results highlight that Illinois’ low population growth (including negative population growth since 2014) and declining labor force are mostly responsible for the decline in the growth rate of civilian employment. It is also obvious that Illinois would have grown faster than the rest of the U.S. economy if the state’s workforce had grown on par with the rest of the U.S. economy.

These results highlight that Illinois’ low population growth (including negative population growth since 2014) and declining labor force are mostly responsible for the decline in the growth rate of civilian employment. It is also obvious that Illinois would have grown faster than the rest of the U.S. economy if the state’s workforce had grown on par with the rest of the U.S. economy.

What’s behind sluggish employment growth?

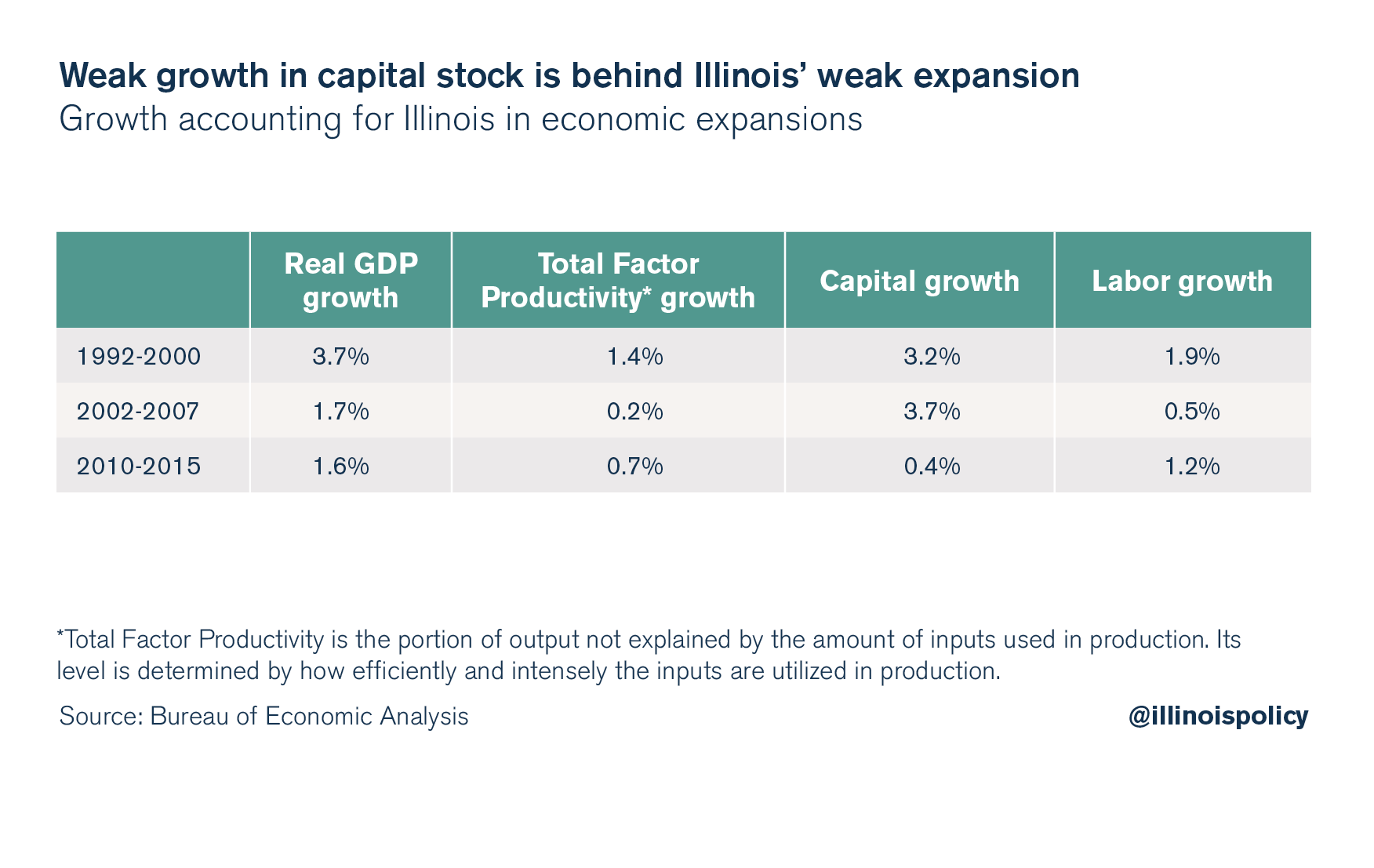

Growth accounting deconstructs the growth rate of an economy’s total output into that which is due to increases in the contributing amount of the factors used in production – capital and labor – and that which cannot be accounted for by observable changes in factor utilization.

An analysis of Illinois’ expansions suggests that the growth rate of the capital stock (the crucial ingredient that makes labor more productive) has declined much more than the decline in labor. The state has experienced a serious decline in investment, and that is causing weaker wage growth. As a result, fewer people want to live and work in Illinois, fueling a decline in the growth rate of employment.

From 2010-2015, private nondurable goods consumption and government spending in Illinois increased to 70 percent of the real economy, compared with only 67 percent during the 1992-2000 economic expansion. Although the growth in all factors declined relative to the 1992-2000 expansion, declining growth in the capital stock was the main culprit. The slowdown in the growth rate of the capital stock is consistent with a decline in investment.

The large decline in the growth rate of Total Factor Productivity is common to most U.S. states. However, a larger decline in investment expenditures is the chief culprit in explaining why Illinois is experiencing its weakest economic expansion in the post-World War II era.

The large decline in the growth rate of Total Factor Productivity is common to most U.S. states. However, a larger decline in investment expenditures is the chief culprit in explaining why Illinois is experiencing its weakest economic expansion in the post-World War II era.

Tax hikes likely reduced investment in Illinois

In 2011, then-Gov. Pat Quinn praised the decision of state lawmakers to raise the individual income tax rate by 66 percent as necessary to address the state’s “fiscal emergency.” The plan raised the individual income tax rate to 5 percent from 3 percent, and raised the corporate tax rate to 7 percent from 4.8 percent. The tax hikes placed Illinois among the top four states in the United States for highest state corporate income taxes, and among the top four in the industrialized world for the highest combined national-local corporate income taxes.

In 2017, two years after the partial sunset of the 2011 tax hikes, the Democratic majority in the Illinois General Assembly, along with a group of Republican state representatives and one Republican state senator, broke the state’s two-year budget deadlock by overriding Gov. Bruce Rauner’s veto of a hike of individual and corporate income taxes. The Illinois income tax rate for individuals went up to 4.95 percent from 3.75 percent, which, added to an increase in the corporate rate, resulted in a $5 billion hike.

Income tax revenues are expected to increase, but at what cost? Although economists are divided as to whether tax cuts always stimulate economic activity, they agree unanimously that tax hikes lead to significant reductions in income and employment. Experts also agree that tax cuts enacted in periods of low or negative economic growth boost real GDP.

Not surprisingly, the share of income attributed to capital in Illinois – investment income – declined, according to Bureau of Economic Analysis data. Lower after-tax returns to investment reduce investment flows, thus slowing the growth of the capital stock and ultimately reducing real wage growth. A real wage decline has negative implications for employment growth and real GDP growth. Even with a highly educated workforce – as Illinois enjoys in the Chicago metro area, for example – a sharp reduction in the after-tax value of employment opportunities and Illinoisans’ purchasing power will fuel Illinois’ outmigration crisis.

The economic impact of tax and spending policy is not trivial. On one hand, higher income taxes penalize labor and capital income, therefore discouraging investments in productive capital. This reduction in productive capital causes labor to become less productive, thus causing the real wage to decrease. Declining real wages have a negative effect on labor supply. On the other hand, a lower after-tax income raises the need to work, save and invest in order to maintain the same living standard.

The first effect lowers economic activity – economists refer to it as the substitution effect – while the second effect raises activity through the income effect. The impact of the tax hike depends on which of these effects dominates the other in magnitude. Essentially, good tax policy implies a tax change that minimizes any reduction in the size of the tax base.

As evidenced by a decline in investment and employment growth, the 2011 income tax hikes were not good tax policy. And there’s little reason to think the 2017 tax hikes won’t have the same effect as Illinoisans look ahead to 2018.

The right policy prescriptions in Illinois should aim to stimulate investment. Policies that lower the cost of doing business and lower barriers to entry into the marketplace would result in higher demand for capital, thus making investment in Illinois more attractive. Illinois will not diverge from its path of poor growth until lawmakers realize the failures of recent tax hikes, and opt for more economic growth instead.

This is part one of a two-part series on Illinois’ struggling state economy. Click here to view part two: “Why the 2017 tax hikes will harm Illinois’ economy.”