What Illinoisans need to know about the progressive income tax

Gov. J.B. Pritzker calls his $3.7 billion income tax hike a “fair tax.” But opponents have criticized the constitutional amendment as a blank check for House Speaker Mike Madigan and other state lawmakers, courtesy of Illinois taxpayers.

Voters will be asked Nov. 3 to trust Illinois state lawmakers with greater power to decide who gets taxed how much and how often.

The Illinois Constitution currently treats all taxpayers the same under a flat tax. The “fair tax” amendment pushed by Gov. J.B. Pritzker would remove that protection and give state lawmakers the power to impose tax rates by simple majority vote on different groups at different rates. It would allow them to add “surcharges,” essentially double or triple taxing the same $1 earned for special spending, such as pensions. It would also open the door for lawmakers to start taxing retirees.

But potentially the most devastating would be the impact of new taxation on jobs and an economy beginning to recover from COVID-19 restrictions. Illinois’ jobs outlook was already failing, but then COVID-19 restrictions hit women and minorities especially hard. The “fair tax” proposal would hurt the pandemic recovery of Illinois’ most dynamic jobs creators, imposing new taxes up to 47% higher on over 100,000 small businesses – drying up funds that could create jobs or allow businesses to return to normal.

Pritzker and lawmakers already set income tax rates projected to yield $3.7 billion in case the amendment passes, and are pushing the message that 97% of taxpayers would see some relief. But that relief amounts to $6 for low-income Illinoisans out of a nearly $1,800 state and local tax burden.

Claims that the middle class will not see an increase might be true at first, but middle class taxes have gone up 13% in Connecticut since they switched to a progressive tax from a flat rate – the only state to do so in the past 30 years. The middle class is where the bulk of taxable income exists, and Pritzker already made $10 billion worth of spending promises from a $3.7 billion tax before COVID-19 put a $4.6 billion hole in state revenues. Moreover, only $200 million of the new tax is expected to go toward the state’s No. 1 fiscal threat – increasing pension costs.

Ultimately, the Nov. 3 referendum is about trust. Trust is a rare commodity in a state where politicians have a history of breaking tax promises and facing corruption investigations into whether they used taxpayer and ratepayer dollars to benefit themselves and their political cronies.

Here are some things voters should know before they decide whether to trust state lawmakers with more taxing power.

How does the progressive tax vote work?

A question asking whether voters approve of the progressive income tax measure will appear on Nov. 3 ballots. The requirements for passage are that the amendment will need either the approval of 60% of voters voting on the question, or greater than 50% approval from all voters who cast ballots in the election.

Here’s a hypothetical example to illustrate how the thresholds work if 5 million Illinoisans cast a vote in the Nov. 3 election, with 4 million of them casting a vote on the progressive income tax amendment:

- 2.3 million Illinoisans vote “yes” on the question (57.5%)

- 1.7 million vote “no” on the question (42.5%)

- Result: The amendment fails. 2.3 million “yes” votes is less than 50% approval from the total of 5 million Illinoisans who cast a vote in the election, and less than 60% approval of the 4 million voters who cast a vote on the ballot amendment question.

If voters approve, how will my taxes change?

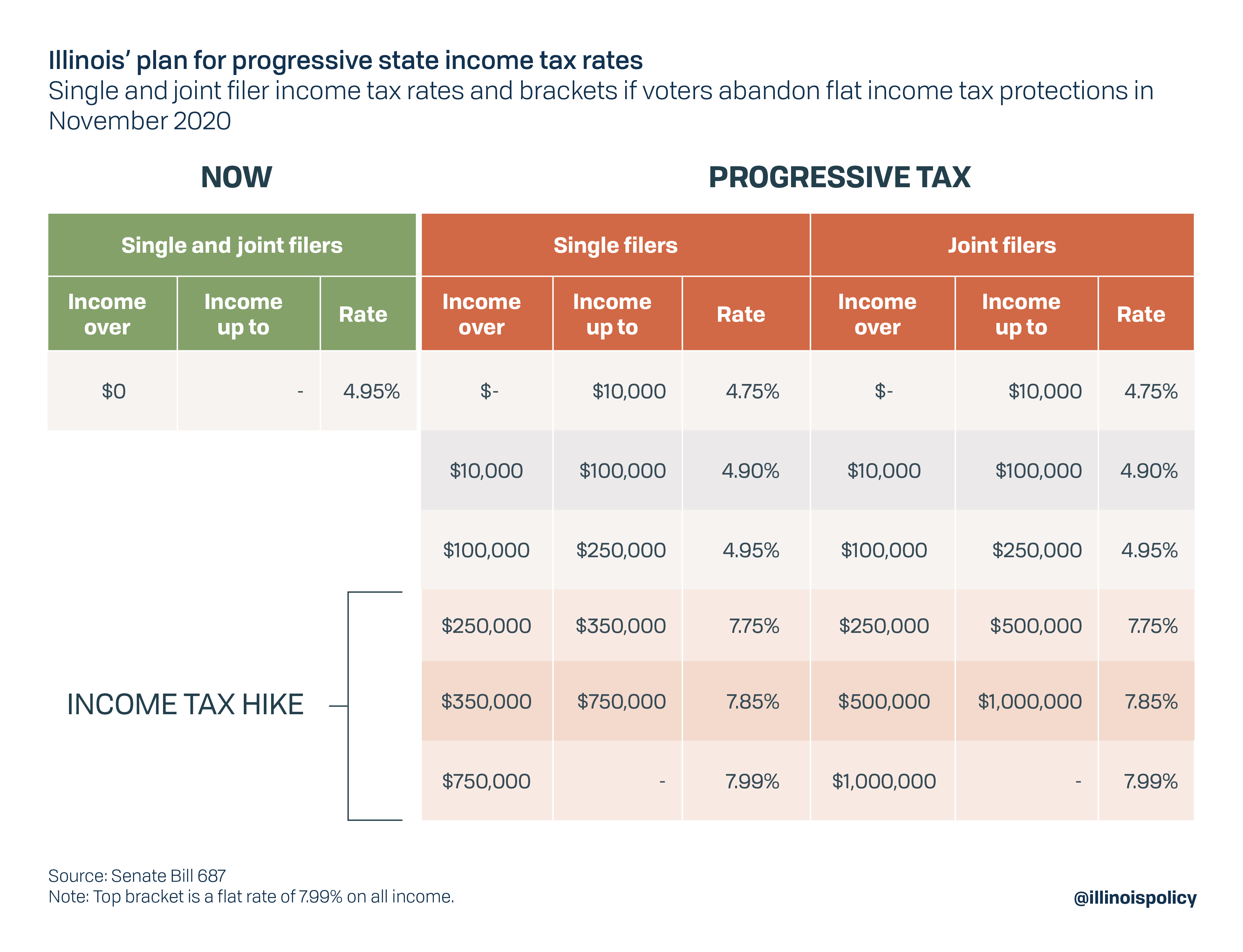

If voters approve the constitutional amendment, and state lawmakers stick with the proposed rates they passed in 2019, Illinoisans will face income tax rates ranging from 4.75% to 7.99% starting Jan. 1, 2021.

Under Pritzker’s proposed progressive tax system, a married couple in Illinois with two kids earning the $106,244 median annual income and paying the average property tax bill of $4,299 would see $107 in total tax relief, according to the Pritzker administration’s online “fair tax calculator.” But if that same family uses two cars on a regular basis, they already saw a $300 tax hike under Pritzker’s capital plan, which doubled the state’s gas tax on July 1, 2019, and hiked annual vehicle registration fees Jan. 1.

For those in the bottom 20% of incomes, Pritzker’s plan saves them $6 on the median average earnings of $12,400. That savings is off their total tax burden of $1,786 – the highest in the Midwest and third-highest in the nation for that income level.

Illinois businesses will also see tax hikes under the progressive income tax plan, regardless of income. In fact, Illinois’ total corporate income tax would rise to the second-highest in the nation should voters approve Pritzker’s constitutional amendment.

Illinois businesses currently pay a total income tax rate of 9.5% – this includes a 7% corporate income tax plus a 2.5% Personal Property Replacement Tax, or PPRT. Under Pritzker’s plan, the total corporate income tax rate would increase to 10.49% (7.99% corporate income tax plus 2.5% PPRT).

That would be the second-highest rate in the nation, behind only Iowa at 12%. Iowa’s rate is scheduled to drop to 9.8% by 2021. Neighbor and competitor Indiana has been consistently dropping its corporate tax rate, with the latest drop to 5.25% on July 1.

The progressive tax impact on small businesses would be significant, both in amount as well as in harm to their COVID-19 economic recovery and jobs outlook. Illinois saw more than 1.5 million initial unemployment claims after COVID-19 impacted the economy, and could permanently lose as many as 21,700 restaurants alone from pandemic mandates. Since the Great Recession, small businesses created nearly 60% of the jobs in Illinois. If Illinois switches to a progressive tax, more than 100,000 small businesses could see tax hikes up to 47% just as they work to bring back employees and recover from the downturn.

What about property taxes?

Property taxes are the single largest state or local tax Illinoisans pay – and rank as the second-highest rates in the nation. Despite rhetoric from the governor that a progressive income tax will provide property tax relief, Pritzker has signed no legislation to make this a reality.

Instead, a Property Tax Relief Task Force was commissioned to identify potential paths toward property tax relief. The task force failed to come to a consensus, missing its deadline at the end of 2019 and all but dissolving amid disagreements over meaningful reforms. One business columnist said property taxes were dragging down Illinois property values well before COVID-19, “yet Illinois policymakers continue to ignore the long-term economic effects of excessive property taxes. A legislative task force appointed late last year to study alternative funding sources for local government services accomplished nothing, lending credence to skepticism that the group was mere window-dressing for Pritzker’s graduated income tax proposal.”

Will the progressive income tax fix state finances?

A progressive income tax will not solve Illinois’ fiscal issues. Despite several massive income tax hikes in recent years, Illinois has failed to pass a balanced budget since 2001. Instead, lawmakers have enacted 20 years of deficit spending. The new budget it included $2.4 billion in new spending over last year and exceeds available resources by nearly $6 billion. At the same time, pension costs are projected to consume more than 27% of the state’s expected general revenues despite deteriorating fiscal conditions, significantly handcuffing spending on services.

Since 2000, state spending on pensions has grown by almost 680% while spending on employee health insurance has grown more than 240%. Without reforms to these massively rising cost drivers, growth in spending will far outpace growth in revenue – leading to inevitable tax hikes.

What have other states done?

In the past two decades, not a single state has switched from a flat income tax structure to a progressive income tax structure. In fact, three states have gone in the opposite direction, scrapping progressive income taxes in favor of a flat tax system. Utah in 2008, North Carolina in 2013 and Kentucky in 2018 all made the switch to a flat income tax structure and cut taxpayers’ rates. Additionally, Colorado voters in 2018 rejected a statewide ballot amendment that would have swapped the state’s flat income tax for progressive rates.

Most states that established progressive income tax structures did so in the early 20th century. The last state to switch from a flat to a progressive income tax was Connecticut in 1996. The initial, small tax cut quickly turned into a 13% tax hike on the middle class. That tax hike did nothing to solve the state’s finances or balance budgets, was unable to stymie growth in property taxes and contributed to a 47% increase in the state’s poverty rate.

Will Illinoisans get a voice on other constitutional amendments?

Illinoisans will not be permitted to vote on other constitutional amendments such as fair maps or term limits, both of which are more popular than the progressive income tax. Despite the widespread popularity of these initiatives, no measures to place these issues on ballots were passed in 2019 or 2020.

Pritzker supported fair maps during his campaign but has largely gone silent on the issue since he took office. Meanwhile, the governor has publicly opposed term limits on lawmakers.

Summary

Although the progressive tax is being sold as a way to shore up state finances, pay down debt and increase funding for services, it will fail to fulfill those promises. Without addressing the structural spending problems that created the highest overall tax burden in the nation, a progressive income tax system would only be a blank check for lawmakers to create rates to support the spending they want, which inevitably will mean higher income taxes for the middle class.

Judging by how quickly Pritzker’s “fair tax” promises have receded and spending promises have grown, it has become clear to taxpayers the ease with which income tax rates could rise under the governor’s plan. Instead, Pritzker and the General Assembly should follow a trustworthy roadmap to tax relief for Illinoisans and restored fiscal health through pension reform and spending restraint.