What goes up must come down: Why Illinois is ill-prepared for the next recession

Poor public policy and inefficient government mean Illinois will struggle to provide relief for residents in need during the next downturn.

Times appear to be good in the United States – at least in economic terms. The stock market continues to rise, hitting several all-time highs this year, and second quarter GDP growth surpassed 4 percent despite an escalating trade war.

But Illinois has not taken this time to get its financial house in order. Instead, the state is in worse fiscal condition than before the Great Recession and may be in for an even longer downturn than the rest of the nation when the next recession strikes.

Many experts believe the current economic expansion in the United States is on track to become the longest in history. That said, this expansion won’t last forever. Since World War II, economic expansions have lasted approximately 58 months on average. The current expansion – albeit sluggish – is in month 111.

No one can predict with certainty when the next recession will strike. Many economists predict it could come as soon as 2020, according to a Wall Street Journal survey. Whenever the next recession does strike, it is unclear how much assistance the federal government will be able to provide, or even how effective any federal action would be.

Despite deficit spending at levels only surpassed during the recovery from the Great Recession, combined with corporate tax cuts – two of the three typical policy prescriptions to stimulate growth – the U.S. is seeing tepid economic growth and meager inflation compared to long-run averages.

The third approach is for the Federal Reserve to engineer a drop in interest rates with the purchase of specific maturities of government debt, or in more simple terms, pumping liquidity into the market. That’s what happened after the Great Recession. But interest rates are now low by historical standards. That means the Fed’s usual tools may not be sufficient to cope with the next downturn.

Despite low unemployment and recent market surges, inflation remains below the Fed’s target, and economic growth is expected to remain considerably lower than it has been in the past because of the influence of a number of structural factors.

When the next recession strikes, the entire country will be hit hard. If that makes national prospects look bleak, it’s even worse for states such as Illinois.

What happens to Illinois during recessions?

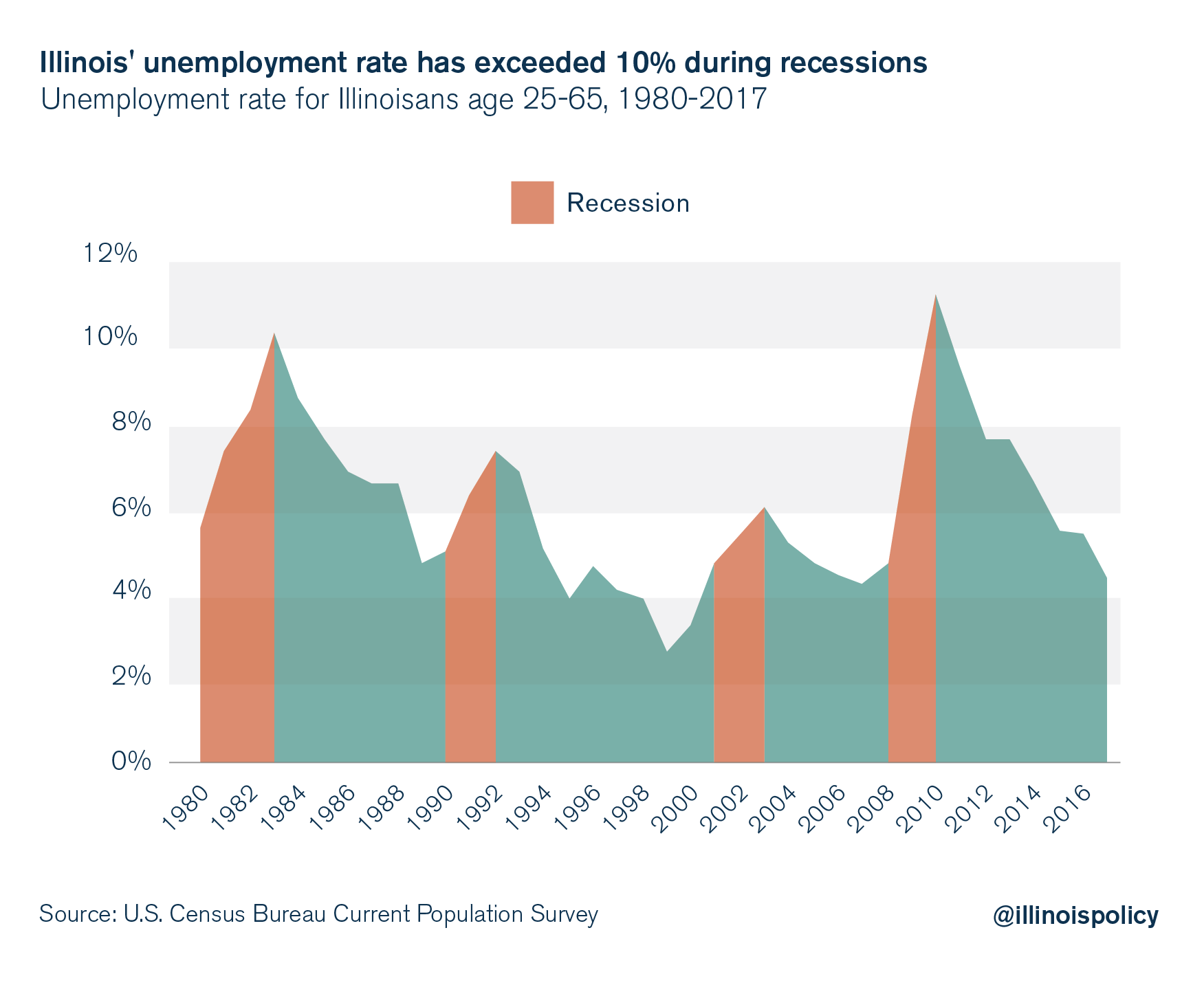

During recessions, the economy contracts, purchasing power drops, and unemployment rises. This also means that more and more Illinoisans fall on hard times.

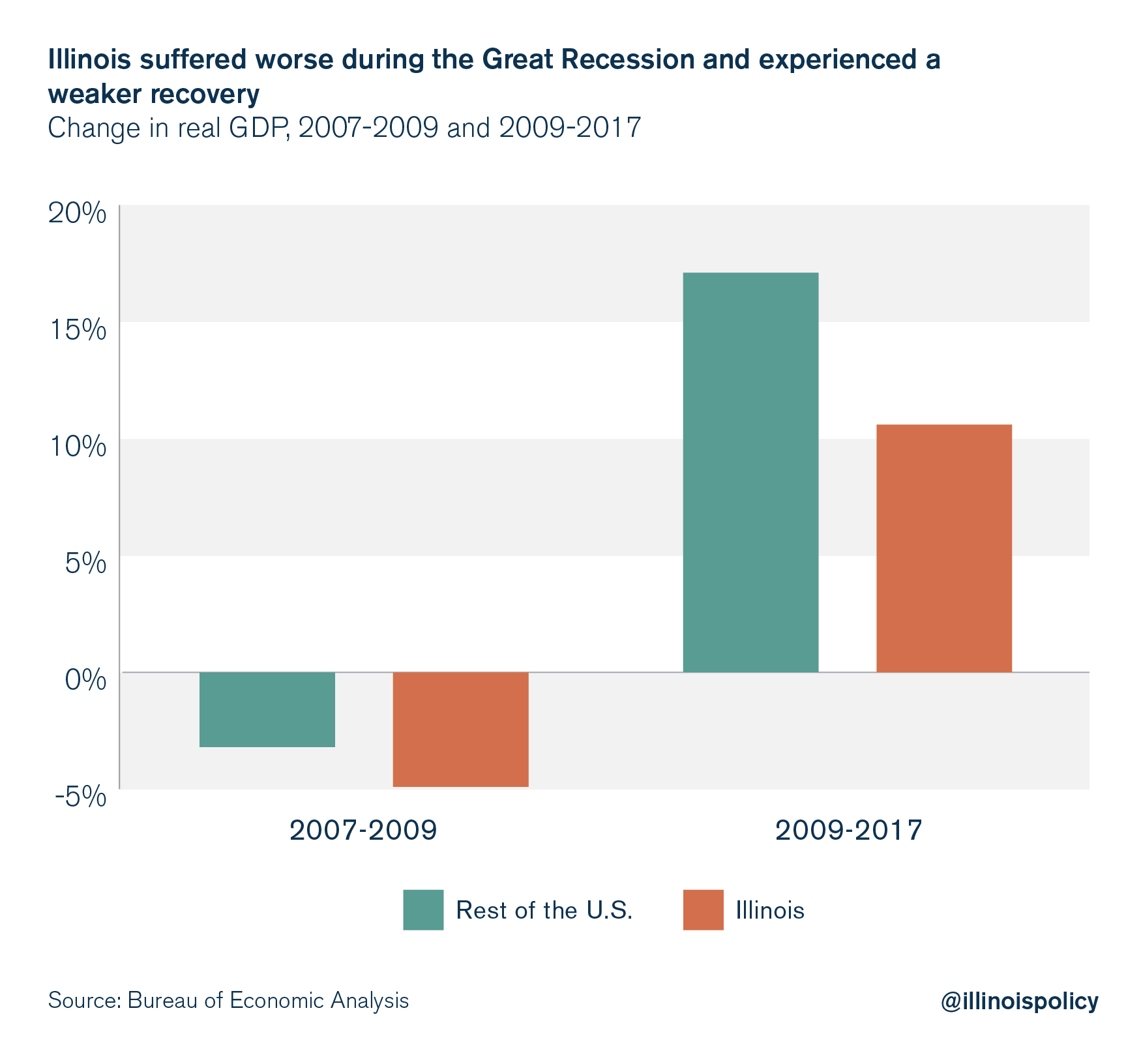

The Great Recession was particularly bad for Illinois, as the state’s economy suffered a worse downturn than the rest of the nation. From 2007 to 2009, Illinois’ economy shrunk by nearly 5 percent compared to a 3.2 percent drop in the rest of the nation.

Illinois has also experienced a much slower expansion in the time since then. From 2009 to 2017, Illinois’ economy grew by 10.6 percent while the rest of the nation grew by 17.1 percent.

Illinois is not prepared for the next downturn

Given that Illinois was severely affected during the most recent recession and has had a comparatively weak expansion, the state is poorly situated for the next downturn.

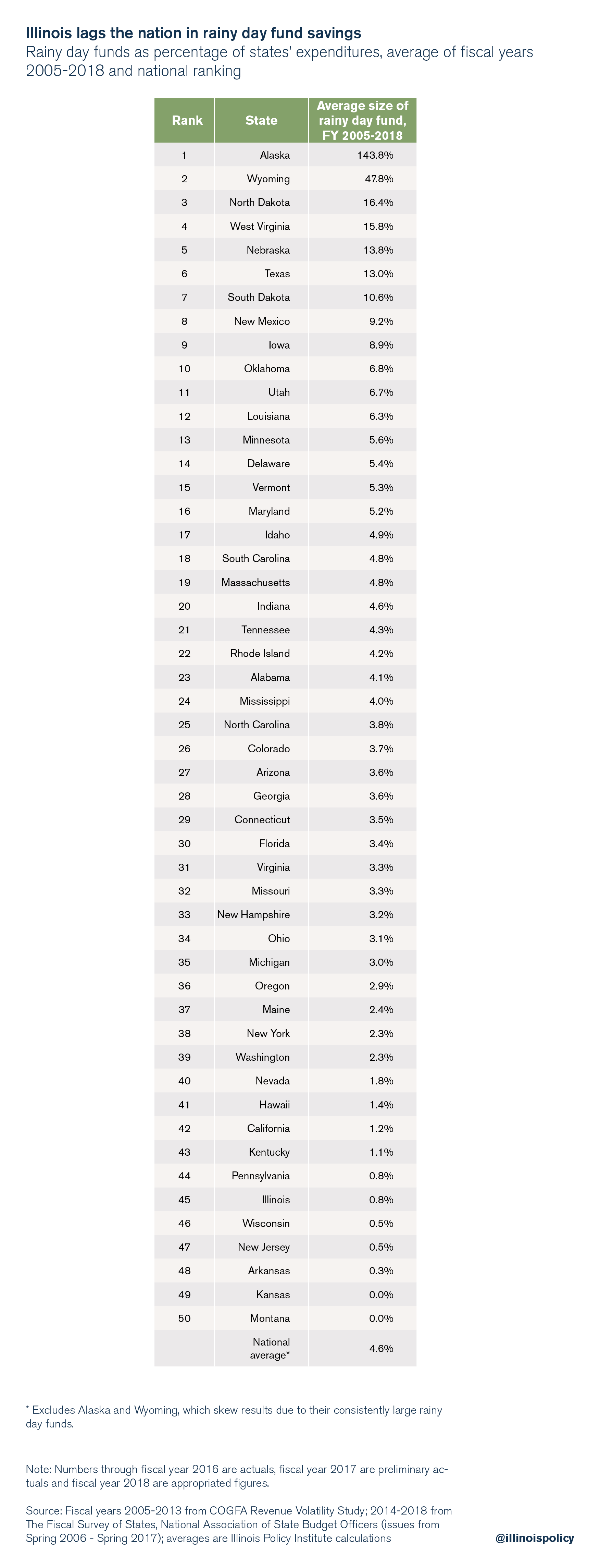

Unfortunately, lawmakers have not taken the necessary steps to position the state government to provide relief during the next recession. Nearly every state has a budget stabilization – i.e., “rainy day” – fund to supplement other revenues in case of economic distress. However, at the end of fiscal year 2018, Illinois had only enough revenue saved in the state’s rainy day fund to cover 81 seconds worth of state spending.

This isn’t an anomaly. On average, Illinois has set aside less than 0.8 percent of the state budget into the fund since 2005. That places Illinois 45th among all 50 states, and far below the 4.6 percent national average. It’s generally recommended that states’ rainy day funds hold an amount equal to 5 percent of annual revenues – although some recommendations suggest 10 percent of annual general fund revenues.

Despite failing to hold virtually any reserve revenues, Illinois’ spending continues to increase during recessions, as many would expect, to provide relief to struggling citizens.

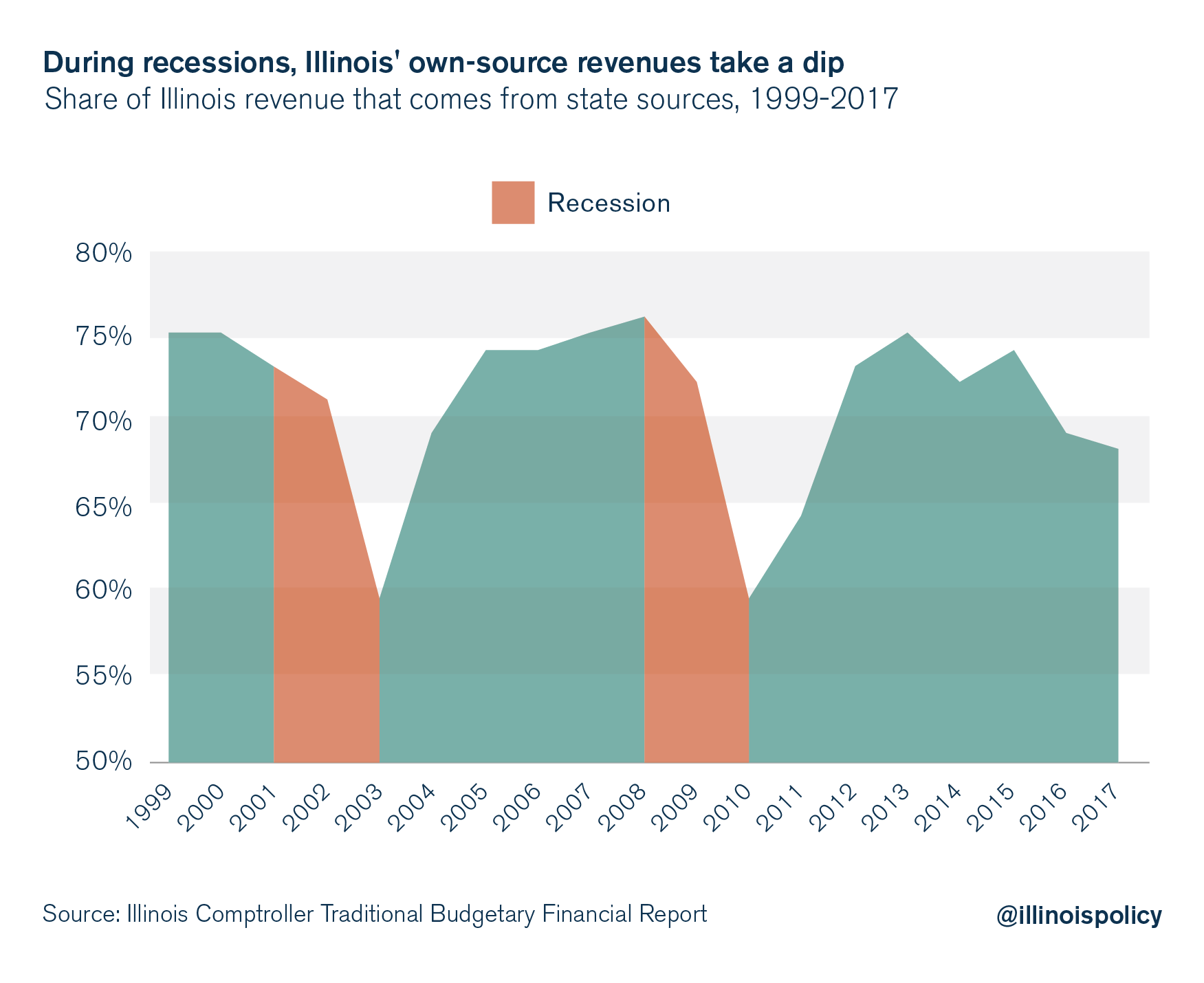

While state spending does not seem to be affected by recessions, economic downturns do affect where the money to fund this spending comes from.

During recessions, the state’s share of own-source revenues (i.e., from taxes and fees paid within the state) declines, and Springfield relies more heavily on the federal government and bond issuances. However, the federal government is already contributing historically high amounts to state revenues. And it is unclear how much more assistance the federal government would be able to provide during the next downturn, as the U.S. has continued to run record deficits during the current expansion.

Furthermore, some economists suggest that persistent deficits could galvanize fear of a government debt crisis, further reducing economic growth prospects. If this is the case, further deficit spending may have detrimental effects, leaving Illinois to rely more heavily on federal money that might not materialize.

If the economy goes south, where will Illinois’ revenues come from?

A recession would result in a smaller tax base for Illinois, something the state can’t afford given its persistently declining population. A smaller tax base would mean lawmakers in Springfield – who only managed to reserve 81 seconds worth of state spending in the rainy day fund – couldn’t rely on tax hikes to generate new revenue. Any tax hike would only serve to push the state deeper into economic turmoil.

Looking elsewhere for revenue, lawmakers may consider taking on debt to finance spending during the next recession. But Illinois has already been relying on issuing bonds to raise funds. Even worse, the lack of meaningful reforms to spending has meant that despite borrowing money, the state has racked up $7.7 billion in unpaid bills and has the worst credit rating in the nation, at one notch above junk. Given Illinois’ consistently sluggish economic growth, taking on more debt without structural reforms is simply not a viable option for the state.

These constraints would leave Illinois only one option in a downturn: Prioritize spending with whatever revenue the state can manage to bring in. However, this is also a difficult task. State pension contributions, which are mandated by the Illinois Constitution, now take up more than 25 percent of the current general funds budget. These costs are scheduled to increase, and if revenue stalls, pensions will take up an even larger share of the budget. Thus, rising pension costs make it likely the state will be able to provide less assistance to families in need during the next recession.

Preparing for the next recession

Illinois needs to do as much as it can today to ease the pain of the next downturn. That means reining in the cost of government to build a healthy rainy day fund and not racking up billions of dollars in unpaid bills.

However, a low-growth environment means state lawmakers must reform pensions as soon as possible so the state can continue providing necessary government services. It also means streamlining government to eliminate waste. To the extent that government spends money, it should be providing services and public investments that stimulate the economy and make citizens more productive, not propping up bloated bureaucracy and paying enormous legacy costs for yesterday’s services. Illinois’ 7,000 units of local government – the highest of any state in the nation – open the door for layers upon layers of waste.

Trimming government costs doesn’t mean cutting necessary services to the bone. It means efficient government that improves communities and provides some relief when citizens need it most. If Illinois doesn’t take steps to do this today, its residents will be far worse off when the next recession hits.