Updating felony theft laws can help Illinois save money without harming public safety

A new study by The Pew Charitable Trusts shows states that adjusted their felony theft laws have not seen an increase in crime. To save on corrections costs, Illinois should update its theft thresholds, too.

Steal an iPhone in Texas, and you’ll be punished – that crime comes with a misdemeanor charge and a sentence of up to a year in county jail. Steal the same iPhone in Illinois, however, and you’ll face a Class 3 felony charge, punishable by up to five years in prison.

Illinois stands out among most other states for its relatively low felony theft threshold. Theft of over $500 worth of goods in Illinois is a felony. Twenty-nine other states have felony theft thresholds that are twice as high or even greater – such as Texas and Wisconsin, where theft below $2,500 is generally a misdemeanor.

To be sure, law enforcement must take property crimes seriously and punish those who commit them. But for low-level property crimes, misdemeanor sentences – that can still come with up to a year in jail or probation – are often a more cost-effective response.

Punishment for property-crime offenders must also focus on the victims of these crimes. An offender in prison isn’t working to reimburse his or her victim for the value of the stolen property. Instead, the victims pay, through tax dollars, to support the people who have wronged them.

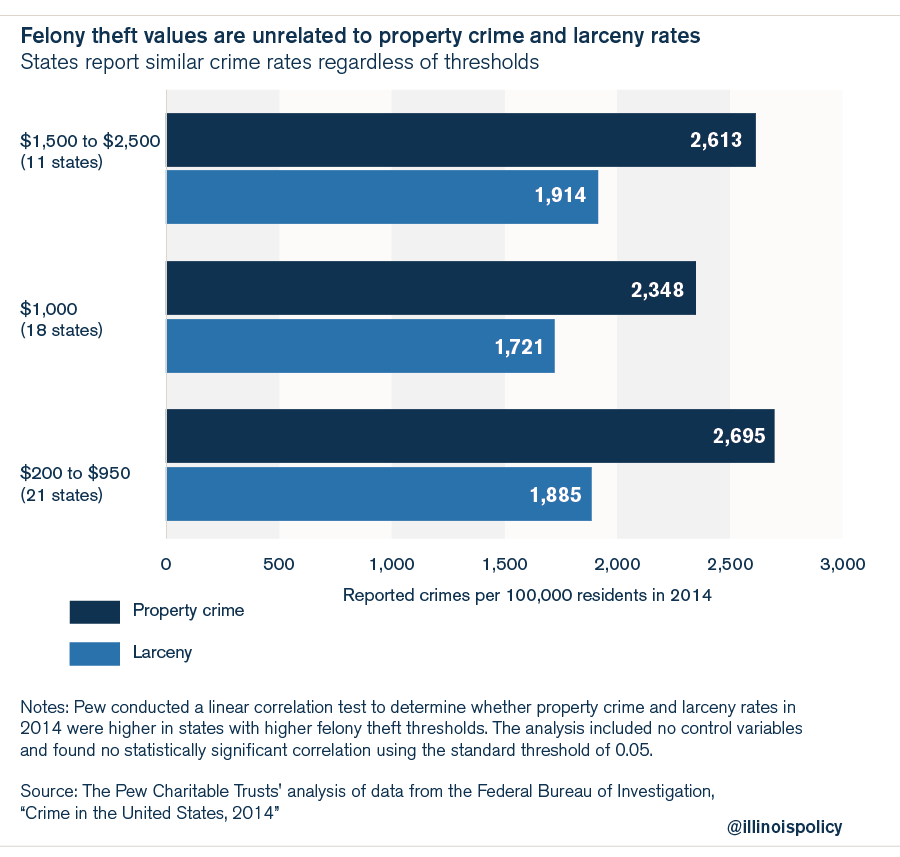

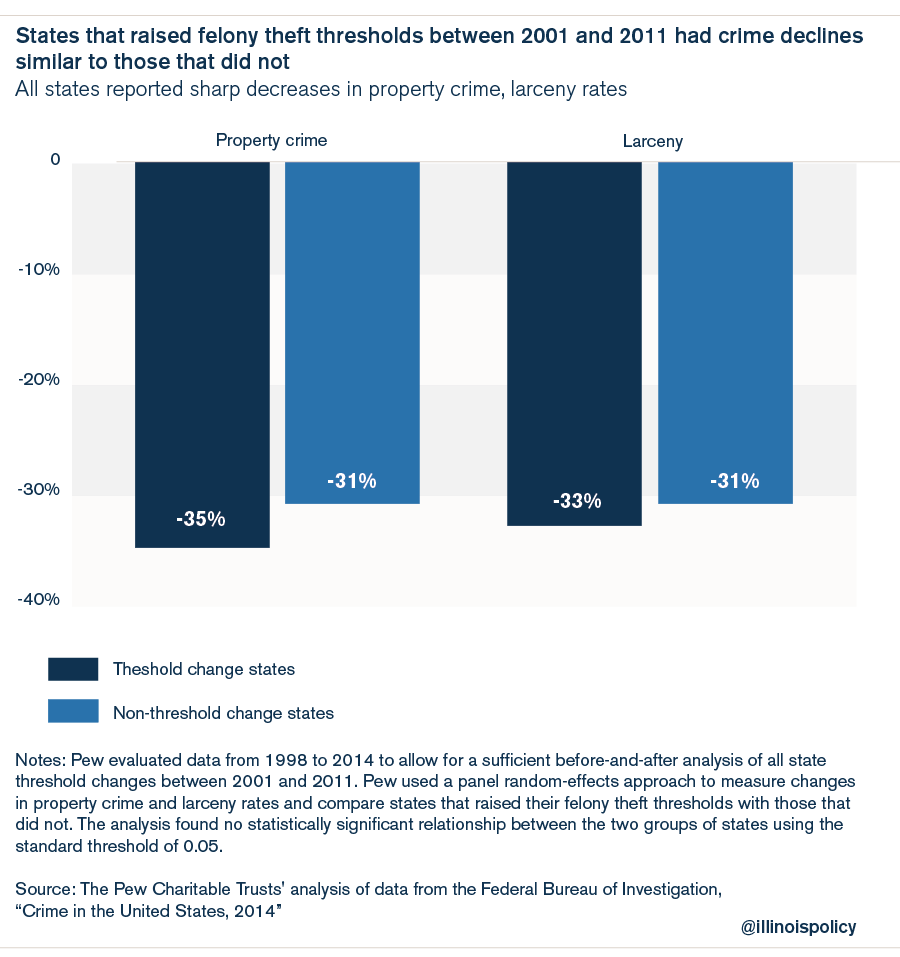

So why not enact these reforms now? Some might be concerned that raising the felony theft level might cause property crime to increase. But newly released data from The Pew Charitable Trusts indicate there’s no correlation between felony theft levels and crime. Thirty states, including Illinois, have raised their felony theft thresholds since 2001. And these states had declines in property-crime rates similar to those of states that didn’t raise their thresholds. In fact, property crime tended to fall slightly more in states that updated their felony theft thresholds. Experts have credited technological innovations, such as CompStat, and improved policing techniques, rather than states’ felony determinations, as major drivers of the property-crime decline, which has continued since the 1990s.

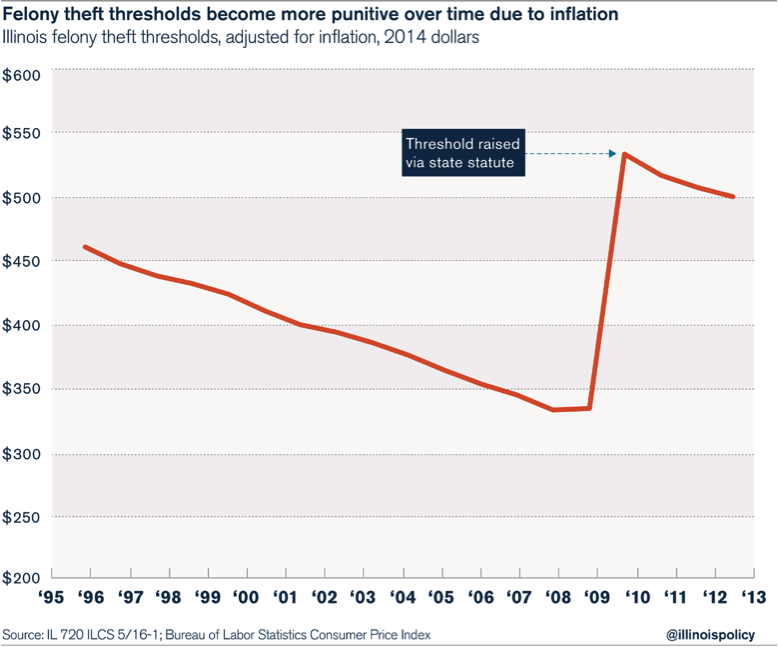

Beyond raising its low theft thresholds, Illinois should also regularly update them based on inflation. Even though the threshold was raised to $500 from $300 in 2010, the state does not update the levels on a regular basis to ensure the criminal-justice system punishes thefts of the same value over time. Someone arrested for stealing a watch worth $250 in 1982 would have been charged with a Class A misdemeanor, and if convicted, could have spent up to a year in jail. Today, that same watch would be worth $618, and stealing it would be a Class 3 felony, punishable by two to five years in prison.

Cost-effective sentencing and helping property-crime victims are not mutually exclusive. States such as Texas have pursued both. Keeping laws up-to-date is critical to saving taxpayer dollars and improving the effectiveness of Illinois’ criminal-justice system. Updating the state’s theft statute is one small step to take to make Illinois smarter on crime.