Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System looks to lower its expected investment rate of return

The Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System’s adoption of more realistic investment return assumptions would cause the system’s unfunded liabilities to grow by about $6 billion above their current $62 billion level.

The Teachers’ Retirement System, or TRS, is considering lowering its expected rate of return from the 7.5 percent it currently assumes its investments will make.

The announcement comes a little more than two years after TRS last cut its expected rate of return. The fund dropped the rate to 7.5 percent from 8 percent in June 2014. The State Employees Retirement System, or SERS, followed suit in 2016, dropping its own investment return assumption to 7 percent.

These actions by TRS and SERS confirm that the pension funds’ expected investment returns have been too optimistic. It also means the magnitude of Illinois’ pension crisis is far larger than politicians have led Illinoisans to believe.

TRS offers guaranteed pensions to its retirees; those benefits must be paid. So if TRS can’t earn its assumed investment returns, that means the state – that is, taxpayers – has to pour more money into the pension system to make up the difference.

A lower assumed investment return rate will mean Illinoisans will be on the hook for billions of dollars in additional pension debt.

If TRS lowers its investment rate assumption to 7 percent, the system’s unfunded liabilities will grow by about $6 billion above their current $62 billion level. It also means taxpayer contributions could rise by as much as $500 million, depending on how much the rate is reduced. When TRS lowered the investment return rate by half a percentage point in 2015, state taxpayer contributions increased by $200 million.

Moody’s Investors Service, the Illinois Policy Institute and other groups have criticized state pension funds’ overly optimistic investment goals for some time. Under more realistic investment assumptions, Illinois’ pension debt actually totals more than $200 billion.

Some will argue that this is a move in the right direction – and it is. The state and pension systems are being more responsible, although the change will put a significant strain on state funding for social programs and other core services in the short run.

But all that misses the larger point. Dropping investment assumptions to more realistic levels only shows that the state’s politicians have been hiding how bad the pension crisis really is. It does nothing to change the fact that the pension funds are fundamentally broken.

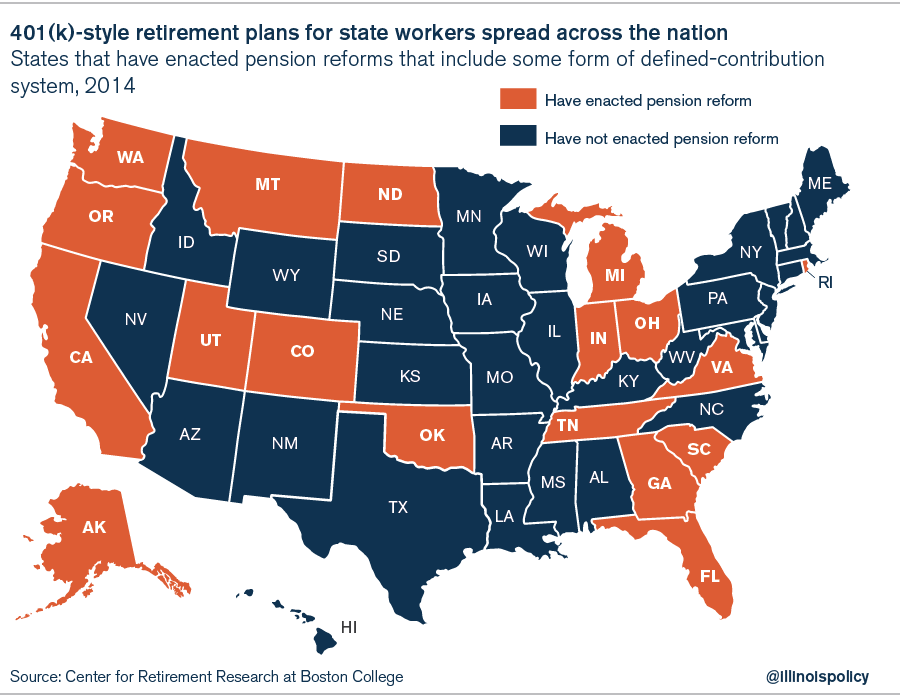

The realization that pensions don’t work has prompted many companies and states to move to 401(k)-style plans. Nearly 85 percent of private-sector companies now have defined-contribution plans, and states ranging from Washington to Rhode Island have initiated some form of 401(k)-style reform. Illinois needs to follow their lead if it’s to solve its own pension crisis.

TRS’ lowering of its investment return rates shows that – now more than ever – Illinois needs to implement real pension reform.

Illinois must move away from its broken pension systems – starting by moving new government workers to 401(k)-style plans and giving existing workers the option to have their own self-managed accounts.

Doing that, in addition to adopting a constitutional amendment allowing Illinois to reform pension benefits going forward, is an important first step in fixing Illinois’ government-worker pensions.