The Edgar ramp – the ‘reform’ that unleashed Illinois’ pension crisis

The former governor’s landmark pension bill paved the way for two decades of go-along-to-get-along pension politics, turning Illinois' pension debt into the nation's largest retirement crisis.

In 1994, Gov. Jim Edgar spearheaded a bipartisan pension bill he claimed would solve the state’s then-$15 billion pension deficit.

“We had a time bomb in our retirement system that was going to go off in the first part of the 21st century,” Edgar told The State Journal Register in 1994. “This legislation defuses that time bomb.”

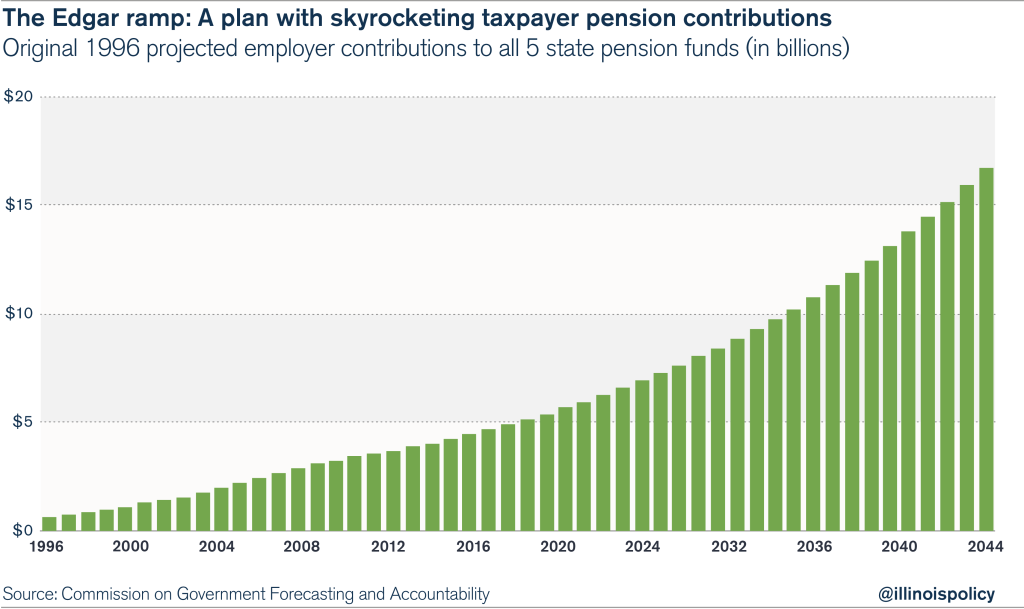

Today, Illinois’ pension debt totals more than $100 billion. That’s because Edgar’s plan didn’t structurally reform pensions. Instead, it simply pushed the state’s pension obligations far off into the future – through 2045 – in the hope that future legislatures would deal with them.

Edgar’s bipartisan bill was politically expedient. His 50-year repayment schedule kept the state’s pension payments artificially low in the first 15 years of his plan, ensuring both sides of the aisle would have more money to fund their current projects.

Not surprisingly, the bill faced no opposition, and it passed unanimously. Government leaders, from future Illinois Senate President Emil Jones to House Speaker Mike Madigan, went along with Edgar’s plan.

Twenty years later, Edgar’s repayment “ramp” is now widely accepted as a failure. Illinois’ pension debt is the biggest retirement crisis in the nation.

But Edgar’s most serious offense wasn’t his irresponsible ramp. His real transgression was in paving the way for two decades of pension politics now wreaking havoc on Illinois residents.

That culture enabled Govs. Rod Blagojevich and Pat Quinn to operate from the same Edgar playbook. They borrowed, taxed and delayed pension payments to deal with the ever-growing crisis. And Madigan signed off – with the consent of government-worker unions – on every one of those plans.

More of the same

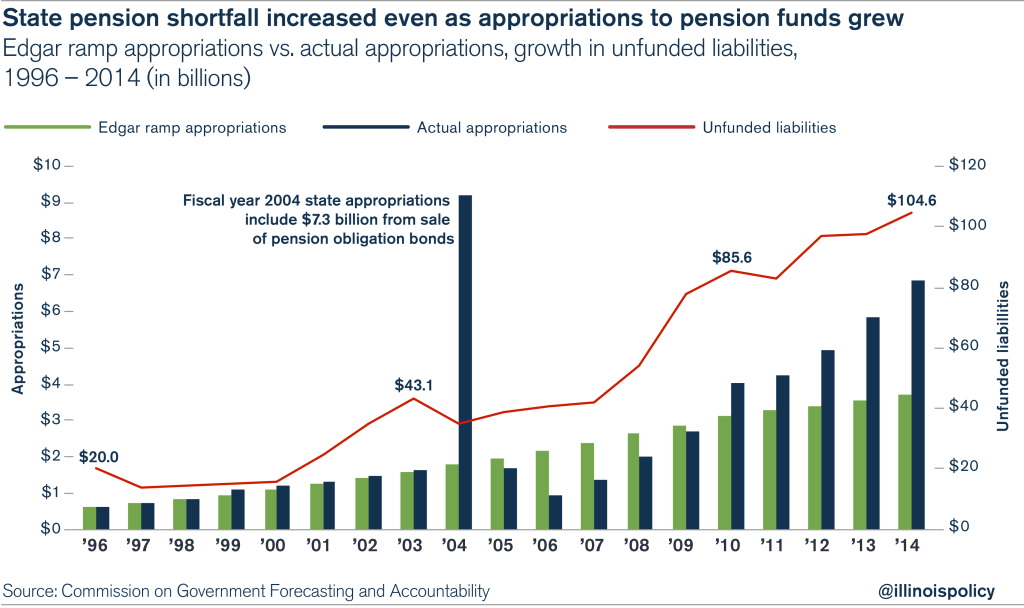

By the time Blagojevich was sworn in as governor in 2003, the state’s pension debt had nearly tripled from the time Edgar passed his bill – to $43 billion.

But rather than pass real pension and spending reforms, Blagojevich immediately borrowed $10 billion – which taxpayers will repay through 2033 – to help plug the growing pension hole.

In search of cash just two years later, Blagojevich and the General Assembly reduced the state’s statutory pension payments. With the approval of three key unions – the Illinois Federation of Teachers, the Illinois Education Association and the Service Employees International Union – the state shorted the pension plans by more than $2.3 billion.

Quinn did more of the same. He borrowed $7.2 billion more to pay for pensions. And when he couldn’t borrow any more, he passed the massive 2011 income-tax hike that sucked more than $30 billion from taxpayers, virtually all of which went to pensions.

The route of borrowing, taxing and pension holidays failed miserably. Even though taxpayers put in $14 billion more than the Edgar ramp originally called for, the pension shortfall spiked to $104 billion by 2014 – seven times higher than when Edgar passed his pension bill.

The real problem

There’s no question that ending the status quo is required to stop Illinois’ cycle of pension underfunding.

But there’s an even more important reason to keep lawmakers from doing business as usual. And that’s to force politicians to finally address the structural flaws in Illinois’ retirement plans, which Edgar and Blagojevich ignored, and which Quinn only began to consider after his borrowings and tax hike had failed.

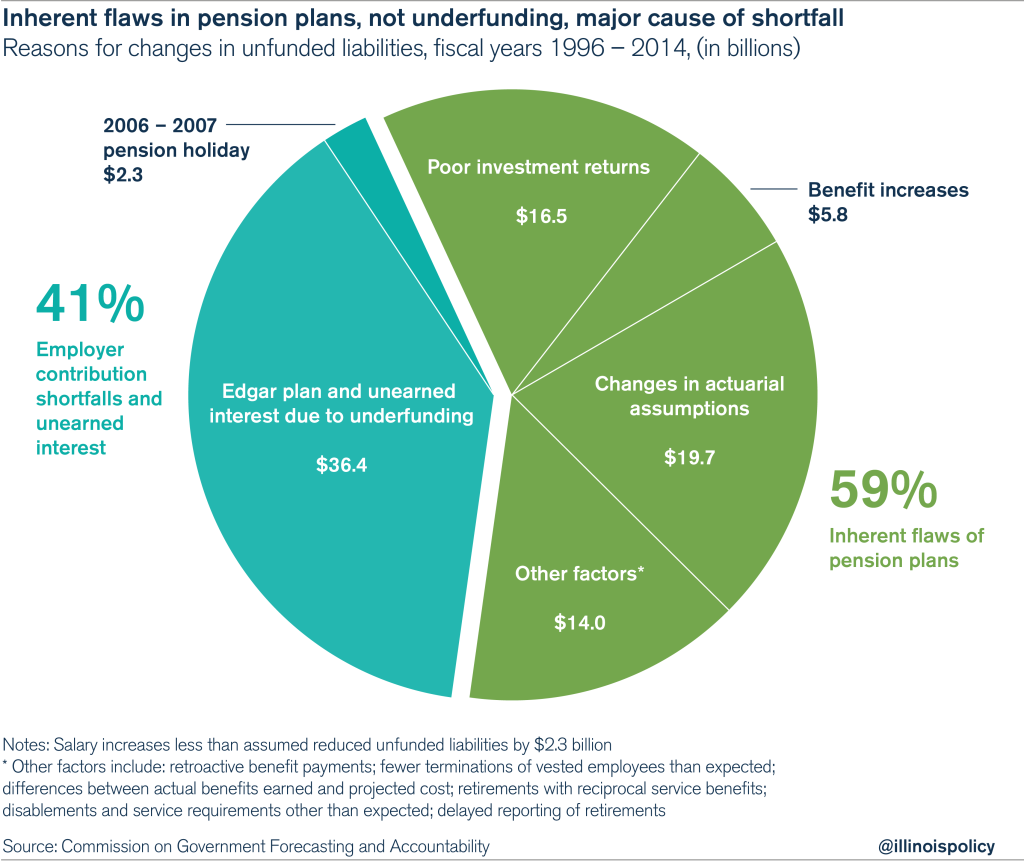

The Commission on Governmental and Financial Accountability recently laid out the causes for the state’s $104 billion unfunded liability. Only 40 percent of the shortfall is due to underfunding.

The remaining 60 percent is due to factors such as workers living longer, overly generous benefits and poor investment returns.

To fix Illinois’ crisis, Edgar and his followers would have been better off working with special- interest groups and the opposition to rein in the costs of Illinois’ retirement plans. They should have addressed the fact that Illinois government workers continue to retire in their 50s with full pensions, despite their longer life expectancies. Or the fact that retirees receive automatic, nonmeans-tested 3 percent yearly cost-of-living adjustments, regardless of actual inflation rates. Or the fact that many workers don’t actually contribute to their own pensions – in many cases their employers pick up those costs as a benefit.

Edgar claimed to have defused the pension time bomb.

Instead, his legacy has left Illinois in shambles.

Illinois’ pension debt will continue to grow until someone is brave enough to stop the bleeding – and that means structurally overhauling government-worker retirements, not prolonging the problem.