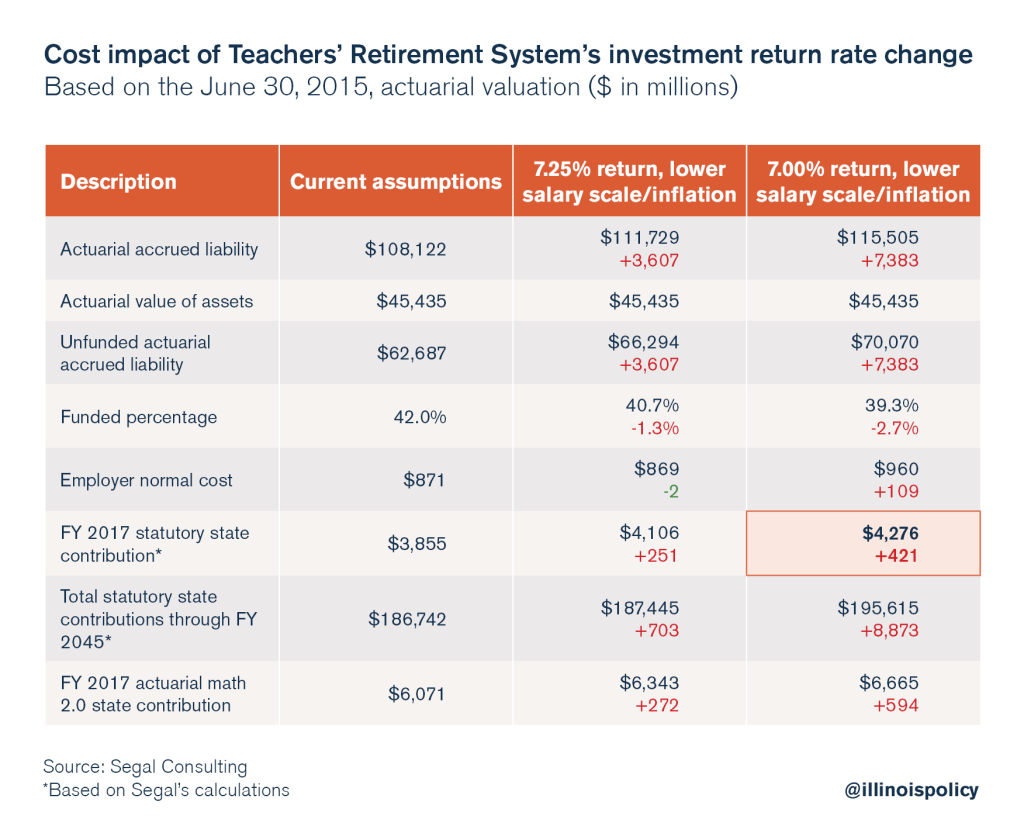

Taxpayers forced to pay $421 million more for teacher pensions

The Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System’s actuarial changes will drive up taxpayer contributions by $421 million in 2017. These latest changes prove Illinois’ pension math doesn’t work.

The Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System, or TRS, has voted to lower the fund’s future investment return assumption to 7 percent from 7.5 percent. Because the fund relies heavily on its investments to meet its retirement obligations, taxpayers, by law, are expected to make up any shortfalls in investment income. The changed assumptions mean taxpayers will pay an additional $421 million toward pensions in 2017 alone.

The announcement comes a little more than two years after TRS last cut its expected rate of return. The fund dropped the rate to 7.5 percent from 8 percent in June 2014. The State Employees Retirement System, or SERS, followed suit in 2016, dropping its own investment return assumption to 7 percent.

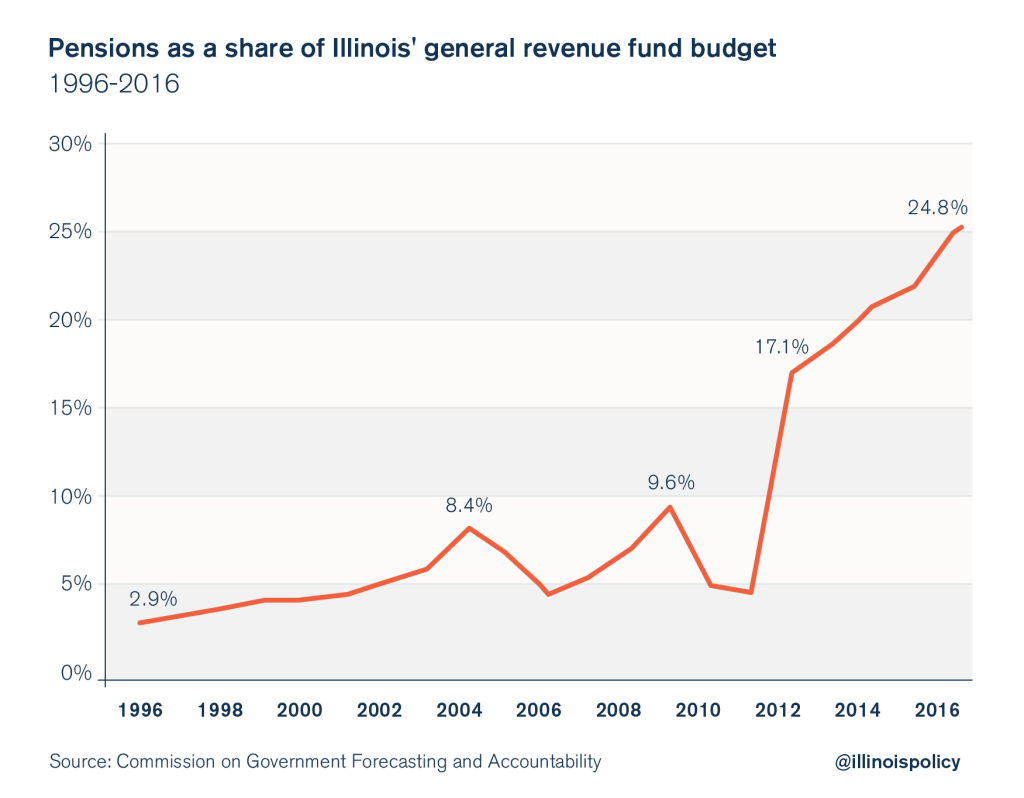

Those changes have already added hundreds of millions to the contributions taxpayers have to make to the state pension systems. Yearly pension costs now consume more than 25 percent of the state’s general fund budget and are crowding out spending on social services, higher education and nearly every other core government service.

But the funds’ projected lower rates of return aren’t just about the increased costs to taxpayers. It’s much more than that. It’s proof that Illinois’ pension math has never worked. Not for taxpayers, not for Illinoisans dependent on core government services, and not for pensioners, whose retirement income depends on politicians’ reckless promises – promises the state could never afford to keep.

Consider that the TRS pension board’s changes to its assumptions were relatively small. Still, those changes have taxpayers suddenly on the hook for hundreds of millions more in annual pension contributions.

But if TRS’s investment rate assumption were lowered to a more realistic 3 to 4 percent – the rates that many professionals, academics and rating agencies propose – taxpayer contributions to TRS would grow by approximately $2 billion in 2017 alone.

TRS’s shortfall makes up a little more than half of the state’s pension crisis. The shortfalls of the other four pension funds – SERS, the Judges’ Retirement System, the State Universities Retirement System and the General Assembly Retirement System – make up the other half. If the two funds for state and university employees, as well as those for judges and lawmakers, were to also lower their expected investment return rates to the 4 percent level, it would mean yet another $1.5 billion more in taxpayer contributions in 2017.

A total of $3.5 billion in additional taxpayer contributions would push the pension systems’ share of the state’s general fund budget to over 35 percent – a fiscal situation that simply isn’t sustainable given the state budget’s other needs and the limited resources of the taxpayers who must fund pensions on top of all the other state spending.

The reductions in expected returns by TRS and SERS are an admission that the pension funds’ expectations have been too optimistic. It also means the magnitude of Illinois’ pension crisis is far larger than politicians have led Illinoisans to believe. If Illinois pension funds were to lower their assumed rates of return to a level financial organizations such as Moody’s Investors Service recommend, Illinois’ state pension debt would exceed $200 billion – pushing Illinois pension plans into virtual insolvency.

The consequences of politicians’ pension deception are galling. Taxpayers 10, 20 or 30 years ago never would have allowed politicians to give out the benefits they’ve given state workers if the true cost of those benefits had been understood.

Instead, unrealistically high expected rates of return and other lofty assumptions hid the impact of politicians’ promises from taxpayers.

According to data from the Illinois Department of Insurance, the pension benefits promised to state workers (also known as accrued liabilities) have grown at a nearly 9 percent pace annually for the past three decades, to $191 billion in 2015 from just $18 billion in 1987.

That growth rate far surpasses the growth rates of state revenues, inflation, household incomes and taxpayers’ ability to pay for those benefits during that same period.

To understand how incredibly fast that 9 percent growth rate is, consider that if an Illinoisan had an annual salary of $28,000 in 1987, which had grown at the same 9 percent rate as the state’s promised pension benefits, that Illinoisan today would be making nearly $300,000 a year.

Now, as the overly optimistic assumptions embedded in pensions are being dismantled, Illinoisans are finally learning the true cost of the benefits politicians have granted to state workers:

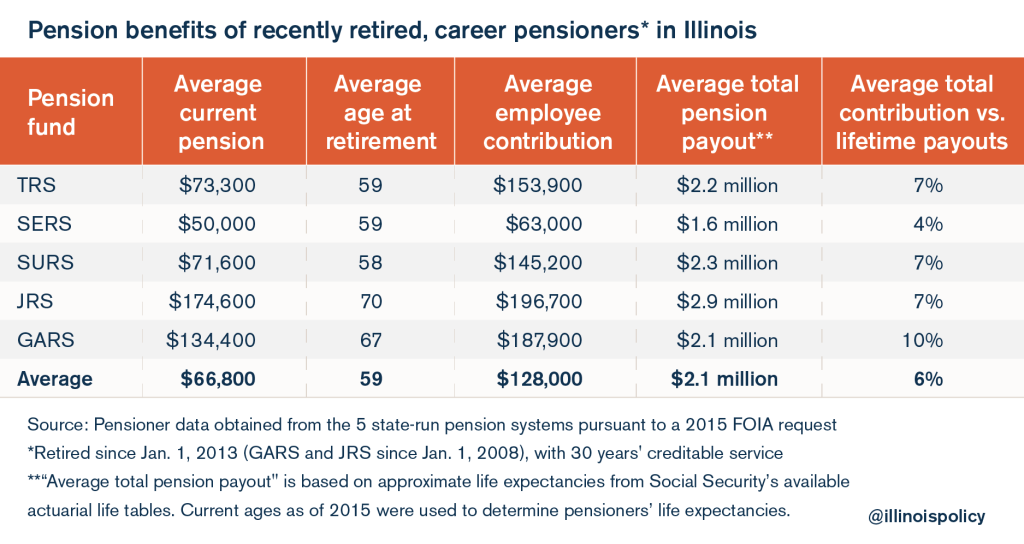

- A majority of state workers draw pension checks while they are still in their 50s.

- State retirees receive automatic 3 percent compounded cost-of-living adjustments to their pensions year after year – which double retirees’ annual benefits after just 25 years.

- A retiree’s annual pension payments are not based on what an employee actually contributes to his or her own retirement, but on the retiree’s final, and often spiked, salary.

The average recently retired career state worker – 30-plus years in the government – now receives $66,800 in annual pension benefits, and his pension will double in 25 years. In total, that retiree will collect over $2 million in total benefits in retirement.

Moving beyond the failures of pensions

The larger taxpayer contributions necessitated by the pension systems’ latest investment assumption adjustments aren’t the real problem. They are the natural result of the failures inherent in defined-benefit plans. As the ill-conceived Edgar pension ramp demonstrates, defined-benefit pension systems simply don’t work.

Defined benefits don’t provide a secure retirement for Illinois’ state workers, they saddle taxpayers with unaffordable burdens, and they’ve diverted needed funding away from core government services.

It’s time for Illinois to progress beyond the failures of defined-benefit plans.