Forgotten Illinois Harvey: Fixing a broken city in a broken state

Most days in Harvey, a suburb 20 miles south of Chicago, are quiet.

Thousands of people and numerous businesses have left the city over the years, and the void left in their wake is plain to see. But on a cold and wet April 14, dozens of longtime residents still fighting for what’s left packed into the House of Prayer Temple Church to voice concerns. In that setting, the city felt full.

“Harvey lacks leadership,” said 40-year resident Carrol Wilson, attending the citizen-led meeting for the first time. “For the city, for the community, Harvey lacks direction. There is no vision for the city. You can see the destruction and perishing of Harvey if you just get in your car and drive around the block.”

“The book I subscribe to says, ‘when there is no vision, the people perish.’”

Others echoed her.

“Harvey has become a dump yard,” said fellow Harvey resident Ruth Cameron, to vocal agreement from the other attendees. “It is a dumping ground.”

The Har-V Community Coalition, a nonprofit founded in 2011 to activate citizens around the city’s major problems, was regularly scheduled to meet that day. But news broke just days prior that put Harvey in the spotlight, and gave plenty of additional fodder for the group to discuss.

National news outlets – such as Fox Business Network and the Associated Press – joined Chicago-area TV stations and newspapers in reporting an eye-catching headline: More than $7 million delinquent on pension payments, the city of Harvey had to lay off 40 police and fire personnel to cover a court-ordered pension payment. The story was a microcosm of Illinois’ financial recklessness and a warning of what’s to come for other municipalities – and the state as a whole – if things don’t change in a hurry. For viewers across the state and country, it painted a picture of what fiscal suicide looked like.

But the pension headline didn’t paint the picture of all Harvey is and was. It wasn’t Harvey’s entire story. Now synonymous with financial mismanagement and political corruption, Harvey was once a destination for businesses and families. It was a place people ran to, instead of away from.

Instead of being a shrinking city, with little to no business and a failing economy, Harvey was once booming, thriving and hopeful. In January 1960, the Chicago Tribune wrote at length about the city’s “boom” through the 1950s. The city gained nearly 6,000 residents and retail sales grew even larger, soaring nearly 90 percent.

“With Harvey’s key geographic location in this area’s dynamic market,” a spokesman for the Harvey Association of Commerce and Industry told the Tribune then, “it is without question that business operations will expand in order to serve the rapidly expanding populations.”

But that growth – in population, property values and business – slowed, then stopped and turned into a sharp decline within a few decades.

That decline is what encourages a group like the Har-V Community Coalition to meet and discuss what the city faces. On the contrary, the decline is also what encourages apathy throughout much, though not all, of the city.

Remnants of what the city used to be are evident throughout Harvey’s empty downtown. Boarded up buildings and houses are reminders of the city’s prior success and its downward spiral.

It’s disheartening. But, for some, it can also be motivating. If Harvey can fall so far, maybe it can rise up again.

Rise and fall

“It was wonderful [when I first moved here],” said Cheryl Jones, a Harvey resident of 33 years. “We had a movie theatre, bakery, 5 and 10-cent store. You could get whatever you needed. Even a grocery store. Now you have more trash on the ground than actual things going on.”

Harvey, for a long while, was the hub of the south suburbs. Not only did the city have the amenities Jones mentions – which other towns may take for granted – but the city had major employers in manufacturing, solidifying its reputation as a strong blue-collar town. That was part of the goal for the city in the first place: Its founder, Turlington Harvey, wanted to plan for a city with a strong industrial base and strict temperance code. While the evolution of liquor laws defeated his latter goal, the former still came to fruition, and for decades Harvey was known as a manufacturing town. Employers like Wyman-Gordon Co., which opened up shop in the city in the 1910s, and Allis-Chalmers, which opened in 1953, were mainstays.

The strong industrial presence fueling the town helped lead to the development of one the nation’s first indoor malls – Dixie Square Mall – built in Harvey in 1966. The mall had as many as 64 stores, including Montgomery Ward, Walgreens and Jewel.

But in the 1970s, in part because of crime concerns, shops started leaving Dixie Square, with Jewel, the last tenant to leave, closing up shop in 1979. The last of the mall can be seen in a classic police chase scene in the 1980 film, “The Blues Brothers.”

The downfall of the once-promising Dixie Square was a sign of things to come. In 1986, both Wyman-Gordon Co. and Allis-Chalmers would close their Harvey plants, affecting nearly 1,000 workers. A rebound never came.

Some Harvey residents have been around for the entirety of the rise and fall.

“It was a destination in the ‘60s, but Harvey started going down when industry moved,” said Chuck Givens, a former Harvey alderman and 42-year resident. “Businesses left. They all left.”

Businesses big and small are now hard to find in Harvey’s city limits. With that, the population has declined each decade since the 1990s. The boom the Chicago Tribune once wrote about is long gone.

Albert Abney was born and raised in Harvey during the decline, but he didn’t realize the problems the city had until he saw the world while serving in the Navy. He lives in Harvey again, now with a family of his own, but has a different perspective.

“Kids don’t realize how bad things are cause they have nothing to compare it to,” he said. “They look at TV as fiction: ‘People don’t live like that.’”

Abney says his daughter asks him often when they might move away from Harvey, with so many doing the same and the surrounding suburbs in much better shape.

Though he understands the question – and sees the reality around him and his family – he wants to stay.

“I try to explain to my kids that, wherever you talk about where you want to live, it started out somewhere,” Abney said. “And if we want Harvey to be a great place we’ve got to build it.”

“What I’m trying to instill in them is when things are messed up you can’t leave … that’s what I want my kids to realize is that if something’s not right, you can fix it. It might take a lifetime, but it’s worth it.”

The engaged residents of Harvey know, given that the problems built up over time, there won’t be quick fixes either. It’s going to take time and effort to bring the city back to prominence.

Looking for leadership

“Harvey has a lot of the same problems other municipalities have,” Harvey Alderman Christopher Clark said, “but takes them to another level.”

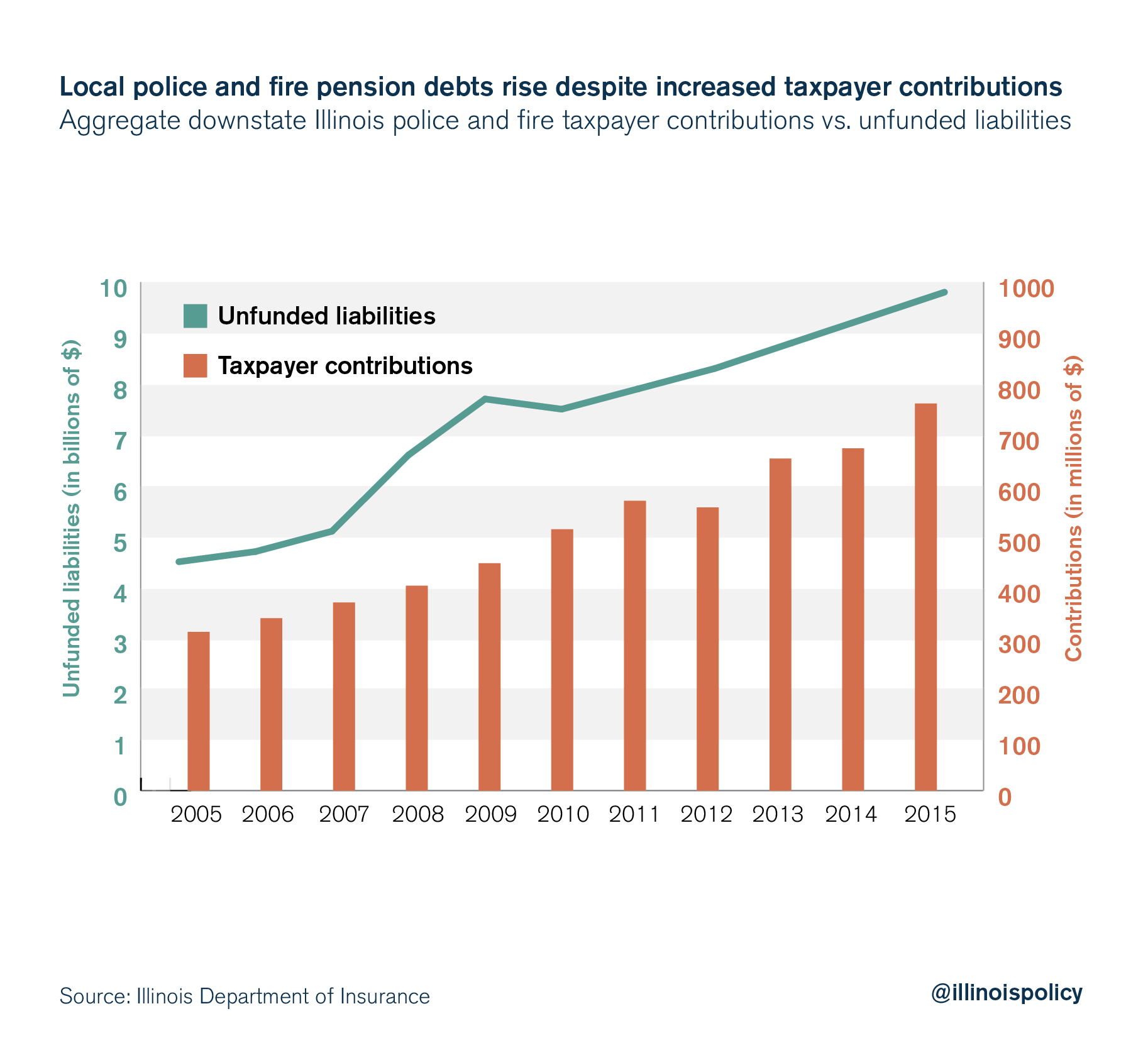

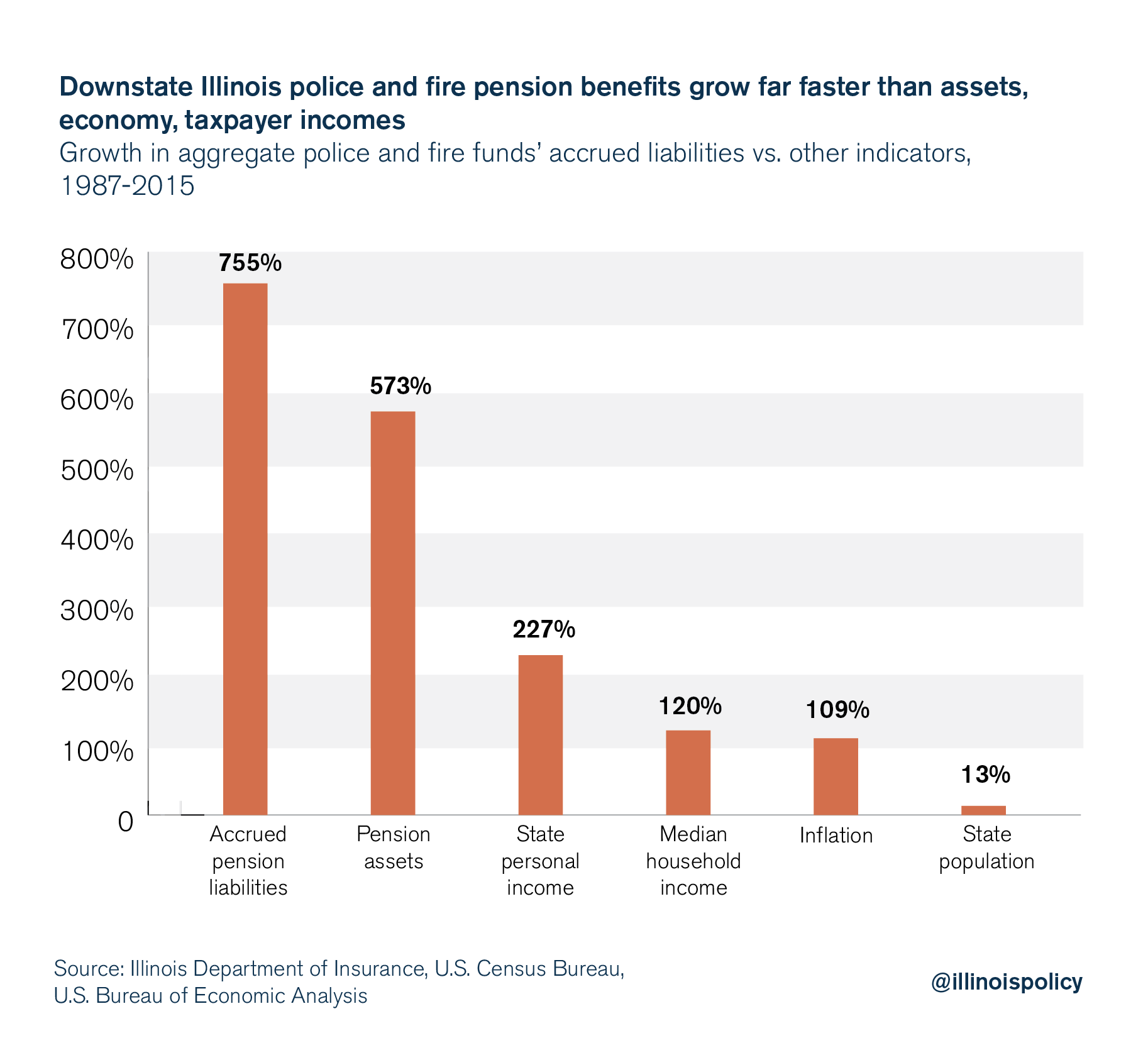

That’s the case in terms of the pension crisis, and a reason so many around the rest of the state and country took note of the story. Many Illinois municipalities are headed down the same path as Harvey, with near-bankrupt pension funds that require more and more property tax dollars from a shrinking tax base. At the state and local levels, pension costs are already crowding out critical priorities such as social service spending and education.

In Harvey, these effects are felt in the extreme.

“[The city] is reacting, they’re not responding [to the pension crisis],” said Woodrow Nunn, executive director of the Har-V Community Coalition. “There’s a big difference in the words. They’re just reacting.”

News stories out of Harvey in recent years back up criticism of current leadership. Current Mayor Eric Kellogg, whose tenure will end in 2019, has been engulfed in controversy, though reelected multiple times.

In 2014, the Securities and Exchange Commission filed charges against Harvey to stop a fraudulent bond offering that the city had been marketing to potential investors. In 2016, Kellogg settled fraud charges by agreeing to pay $10,000 and never participate again in a municipal bond offering. Around the same time, Kellogg used federal grant money to buy himself an SUV instead of what the money was intended for: two new police cars. And in 2018, the FBI began investigating allegations that a consultant to Kellogg demanded tens of thousands of dollars in kickbacks from developers for city approval in real estate deals.

The list of scandals goes on and on, and with it, public trust dies and apathy grows. This is an extreme of what the state as a whole faces: According to a Gallup poll released in February 2016, only a quarter of Illinoisans are confident in state government. That was the lowest rate in the nation.

“We have potential,” Givens said. “But we have not had good leadership.”

Givens and Abney have both tried their hand at running for mayor before. Abney felt the pushback of speaking up during his race when his campaign office in 2015 was vandalized and later burned down, which he and others feel was politically motivated.

Whether or not it was, residents are continually feeling burned out on the status quo. With corruption and mismanagement becoming commonplace for so long, it’s easy to give up.

“Stone cold apathy,” Nunn said. “People say ‘I could care less. [The politicians] are going to do what they want to anyway.’”

“I hate that attitude.”

Losing your home

Though the Harvey from the 1950s and 1960s is gone – and boarded up houses and empty storefronts silence the city – Harvey residents are still being handed a large bill.

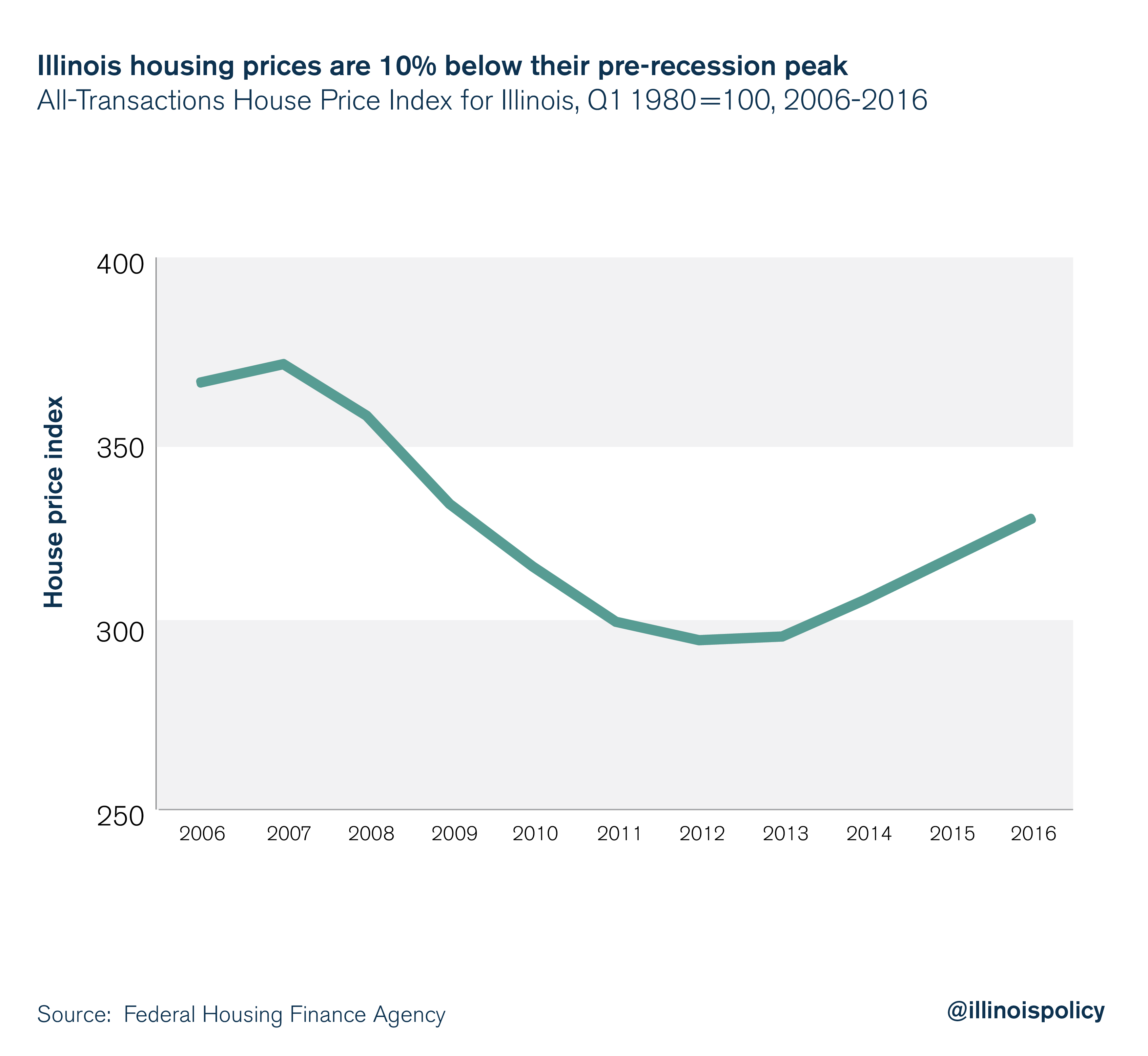

As of 2015, the effective residential property tax rates in Harvey approached 6 percent of home value, while the effective rate on businesses was over 14 percent, according to analysis from the Chicago Tribune. All the while, the value of homes in Harvey fell nearly 60 percent from 2007-2015.

“Your property taxes will eat you up,” Jones said. “Even investors don’t want to touch this. They’re going to put maybe $50,000 or $60,000 in the house and their property tax is going to kill them. Who is going to buy it?”

While property taxes suffocate residents, that question Jones asks does not solicit a good answer. Over the last several decades, as Harvey has dropped in population and remaining residents have had to foot the bill, few have decided to open up shop in the city in part because of fear for that bill – on top of the corruption and uncertainty.

“We have no businesses,” Jones said. “We have nobody coming in. We don’t need any more strip clubs. We don’t need any more liquor stores or used car lots.”

Clark sees the burdensome property taxes – among the highest in the state – as justifiably a major point of frustration for the city when residents don’t see services or quality of life improve.

“The cost of living is high in a relatively impoverished community,” Clark said, “and this is what we get?”

Much like the pension crisis, other municipalities are steps away from finding themselves in the same situation as Harvey.

Downstate communities such as Danville, East St. Louis, Kankakee and Granite City have fire pension funds all less than 30 percent funded and police pension funds less than 40 percent funded. Alton is in the same boat as well, with a fire pension fund right around 30 percent funded and a police pension fund under 40 percent funded.

In a bind, Danville passed a property tax hike in 2017 to pay for its virtually bankrupt pension fund. Local property owners in the struggling city now face a dedicated annual fee of up to $1,020 just to pay for pensions. Kankakee in 2018 chose to hike sales taxes, with the additional revenue directed entirely to the local pension funds. In Alton, officials are moving forward with a plan to sell the city’s water treatment plant to cover an upcoming $8 million police and fire pension bill.

But ultimately, hundreds of millions of dollars in additional taxpayer contributions across Illinois have not been able to keep up with the rapid growth in pension benefits, which are mandated by the state – not local governments.

Unfortunately, too many statewide trends are closer to the reality in Harvey than political leaders might want to admit.

Illinoisans saw their property tax bills grow six times faster than household incomes from 2008-2015. And government data suggest that as of 2016, home prices in Illinois were still down 10 percent compared with 2006. The phenomenon of rising property taxes without new or better services – and the resulting hit on home equity – is by no means limited to the south suburb.

While other towns are headed down the same path, Harvey’s property tax burden has already reached a completely unmanageable point for many homeowners.

Not only are more vacant or burned up homes popping up left and right – as much as 20 percent of the city’s 12,000 homes are abandoned – but current property owners might be rejecting their tax bill, too. More than 4,000 property tax bills in Harvey have gone unpaid to start 2018, by far the most of any municipality.

Government should need to reform in order to meet the declining tax base, but that hasn’t been the case. The Harvey Public Library District – which in 2015 issued $6 million in bonds to pay for a facility expansion – has found itself struggling to keep up with its bills due to a decline in property tax revenues.

“Just a couple years ago, I asked for raises for [library employees],” said Sandra Flowers, Harvey Public Library director, at a May library board meeting. “It just seems like the taxes just fell off the cliff for some reason. I don’t know what happened.”

The answer – as most of Harvey already knows – is taxpayers have been tapped out.

Vision

After years of being abandoned, Dixie Square Mall was finally demolished in 2012. Then-Gov. Pat Quinn joined Kellogg and other south suburban officials in February of that year to announce the start of the demolition, with a hopeful tone.

“Where there is no vision, the people perish,” Quinn said at the time, quoting the same proverb Wilson would reference at the Har-V Community Coalition meeting six years later. “We have a vision for the south suburbs and we’re going to build anew. When people come through here in a year or two, they’re going to see something very special.”

In 2018, remaining residents are still waiting to see something special. More than 30 percent of residents live in poverty and the unemployment rate hovers over 20 percent. And residents outside Harvey – from news stories breaking this year – have seen on TV and in newspapers a bit of that need as well. State and local politicians have turned their backs on Harvey. With that, change might need to start with citizens.

“Harvey ain’t gonna change because of Hillary or Trump, J.B. or Bruce Rauner,” Abney said. “Harvey is going to change if we want it to.”

Other municipalities looking at Harvey as a cautionary tale might need to start at the citizen effort, too, to demand change to get back on the right path. For many towns, plenty of potential exists if local governments can right their fiscal ships. Harvey is no exception. The state could empower local leaders by eliminating burdensome mandates on municipalities, allowing them out from under costly contracts and perhaps even allowing bankruptcy, when it becomes the only option. Pension costs will continue to strangle local budgets without swift action.

If empowered, Harvey’s potential could be unleashed.

The old Dixie Square location is now 39 acres of nothing. Boarded up homes and empty storefronts occupy many of the streets around it. There is plenty of space for a vision.

“I want the lawmakers, the policy makers, people who have investments, to come out here, look around and talk to the people and know this is America too,” Abney continued. “We need our piece of the American dream.”

“The people in this city are worth saving.”

Have a story to share?

Tell us how a state or local policy affects your life.

If we decide to feature your story, one of our writers will reach out to you directly.