Forgotten Illinois Decatur: The Soy City’s search for its comeback

Central Illinois, historically, has been known for its strong agricultural and manufacturing roots.

And that reputation isn’t just local, it’s global.

“The first time I had heard of Decatur I was looking at a sewer cap manufactured here – in Paris, France,” said Christine Gregory, the CEO of Dove Inc., a Decatur-based nonprofit providing programs and services to those struggling in the city.

“This community has been here as an industrial giant in this country for a very long time.”

Gregory is right – and Decatur’s rich history as an industrial giant still manifests itself today. One of the bigger cities in central Illinois, not only does Decatur still have a few large manufacturers left in the city, but maybe more apparent, the city’s blue-collar identity resonates with its longtime residents.

That’s true for much of the region, but perhaps nowhere more so than Decatur, nicknamed the Soy City for its soy production.

Decatur had built up a reputation as a manufacturing powerhouse through the 20th century, providing jobs and opportunity to countless families. But as the state of Illinois began down the opposite path, so did Decatur.

In January 1990, Decatur started to see its first significant dip in population after decades of growth. From then until January 2017, the state of Illinois lost nearly 400,000 manufacturing jobs. Decatur, the industrial giant, felt it.

“At a time, Decatur had several big manufacturers and now you have very few,” said Dave Jordan, owner of the popular area restaurant, The Wagon, for 37 years. “It was a big blue collar town, good town. And it’s just lost a lot of good jobs.”

Once growing, the city is now shrinking. Once thriving, there is now fear of crashing.

Efforts within the city – such as Dove, which helps combat all the “unmet needs” of the community, such as homelessness and domestic violence – exist to fill the voids. But with a history so rich, and a decline so steep, some type of rethinking might also be needed to turn the tide of a city that year by year continues to see its identity slip away.

“Decatur needs to think bigger,” Gregory said. “Just because we’re just Decatur doesn’t mean we have to be just Decatur. We can be so much more.”

From boom to bust

On Thursday, May 27, 1920, Decatur received confirmation on what the city already could feel: It was booming.

Decatur’s 40 percent increase in population in the 1920 census, released that day, made it the sixth-largest city in Illinois – up from 10th-largest just 20 years prior – and as the Decatur Herald reported then, “a cause for rejoicing through the day.”

“The explanation for Decatur’s exceptional development was to be found in the statistics of manufacturers,” the Decatur Herald reported May 28, 1920. “The amount of capital employed in industry in Decatur … had been doubled between 1900 and 1910, with a doubling of the number of workers employed.”

Decatur was a force. That same year, 1920, Decatur would be one of just 14 cities with a team for the inaugural season of the American Professional Football Association, which would go on to become the National Football League. The city’s economic strength would even be reflected in the city’s football team, named the Staleys, after corn producer A.E. Staley, before then becoming the Chicago Bears.

Decatur’s first service station was built five years prior in 1915, helping with the advent and increase in use of motor vehicles. That station still stands today, as a service and gas station, across from Millikin University.

John Phillips Jr., Gregory’s brother and the current owner, has a newspaper clipping in his office showing the service station through the years. Since opening in 1915, the station evolved. Standard Oil took it over in the 1960s. Now owned by Phillips’ family, Millikin students and faculty, as well as other Decaturites frequent it.

That location, sitting for over 100 years, has seen Decatur change around it, too.

“There’s been a steady population decline, as people leave not just Illinois but specifically leave Decatur,” Phillips said.

“I like to say Decatur has all of the drawbacks of a big city with none of the benefits.”

Some of those drawbacks come in the form of financial pinching from city government. For Phillips, Decatur’s 5-cent-per-gallon gas tax is particularly painful in his line of work. He says would-be customers can easily go to neighboring towns and avoid that fee, putting him at a disadvantage.

For Jordan – who left a job at Illinois Power 37 years ago to open The Wagon restaurant – it’s Decatur’s 2 percent food-and-beverage tax.

“Like with any tax, who gets stuck with it, but the consumer,” Jordan said. “Eventually the consumer has to buy it. And it becomes harder and harder with an older clientele and older population because they’re living on fixed incomes, so you raise the tax one percent or two percent or whatever it makes it difficult for them because they have no means to make that up.”

“It’s hurt. It’s hurt sales because people just can’t afford the increases.”

And most business owners in the area have been hit with burdensome property taxes. Phillips said in one year his property taxes went up to $28,000 from $8,000. He appealed that bill down to $16,000 the following year. Decatur City Council hiking property taxes nearly 15 percent in 2015 didn’t help matters.

The numerous tax hikes have been Decatur’s way of trying to compensate for a declining population, and therefore declining revenue. In December 2017, the Decatur City Council passed a budget more than $3 million out of balance. The deficit was fueled in part by a decline in revenue streams such as sales taxes, cable taxes and hotel taxes – the result of a shrinking tax base.

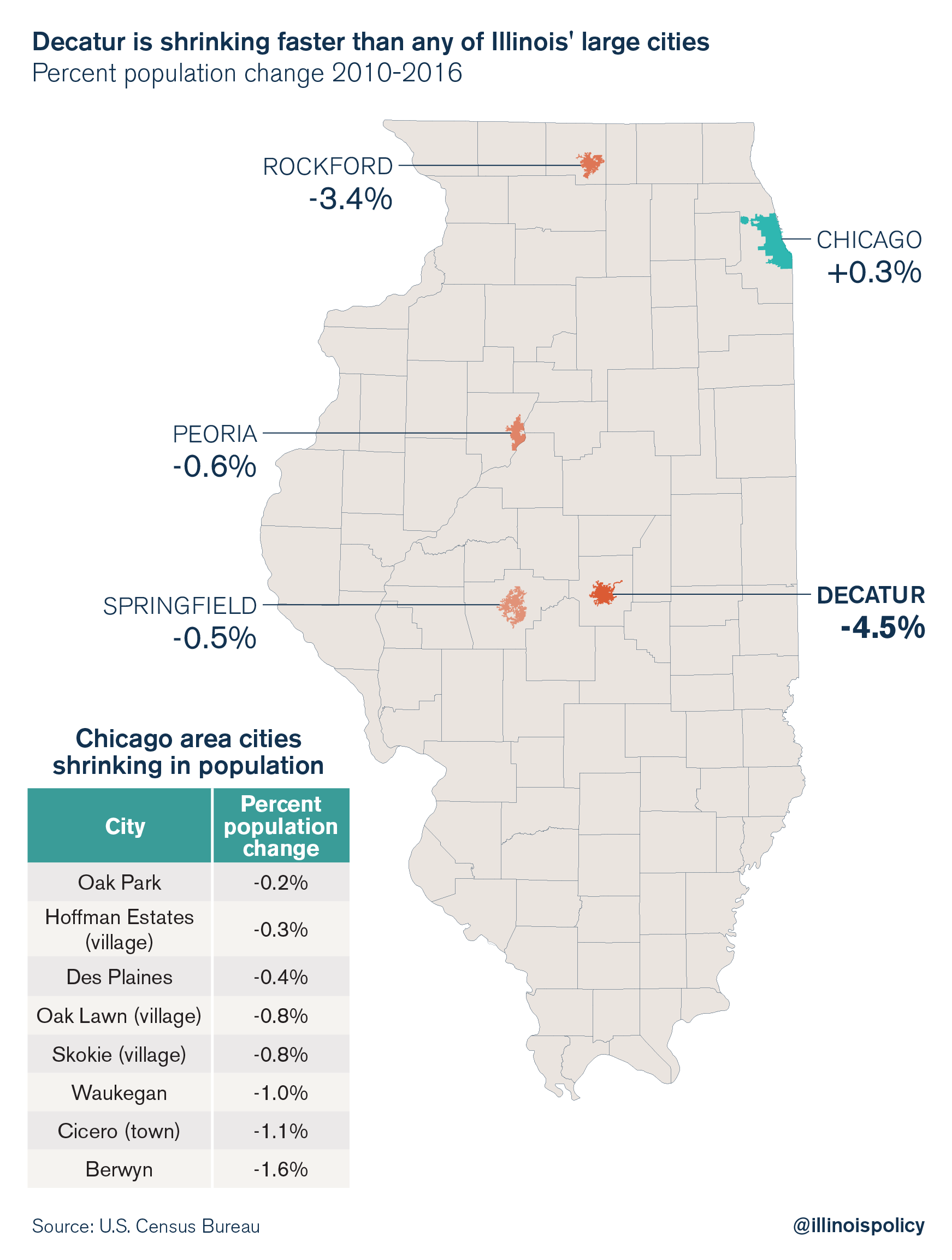

From 2010 to 2016, Decatur was Illinois’ fastest shrinking city with a population drop of 3,400, or 4.5 percent. Among Illinois cities with a population over 50,000, that was the worst mark on a percentage basis.

That drop cuts state funding to Decatur, too. Fewer people means fewer state tax dollars.

Losing residents – and therefore losing tax revenue – could lead to further tax hikes on remaining Decatur residents. For business owners like Jordan and Phillips, firmly planted in Decatur, the financial burden is about making adjustments.

“I probably don’t have as much control as I did 30 years ago,” Jordan said. “I just gotta go with the flow, just like everybody in Decatur has got to. You gotta go with the flow. Things are changing. You gotta learn to deal with what you have left.”

A former place for opportunity

Zane Peterson, a Decatur-based real estate agent, doesn’t have a common Decatur story, by his own admission.

Peterson grew up in the Chicago suburbs but came to Decatur to attend Millikin University and stayed after graduation. He opened a Chicago-style hot dog restaurant on campus with his father while he was still in school, which is still open seven years later, and landed a real estate job after college.

He loves and believes in Decatur.

“I grew up in Chicago. I moved here, my dad moved here. Totally an outlier,” Peterson said. “Most people who grew up in Decatur who are my age end up going to school and going elsewhere. They don’t want to come back to Decatur.”

“I think there is quite a bit of opportunity still in downstate Illinois.”

Once upon a time, Peterson’s story and attitude would not have been so rare.

By 1966, Decatur had become the fourth largest city in the state, behind only Chicago, Rockford and Peoria. The city was up nearly 9,000 residents from the 1960 census. The boom that was felt decades prior hadn’t slowed down.

Corey Walker’s grandfather took advantage of the city’s growth, having moved to the thriving Decatur from Bronzeville, Tennessee, to start a new life and raise his family.

“My grandfather moved up here for employment,” Walker, a lifelong Decatur resident, said. “Wagner Castings back in the ‘60s was hiring African Americans in record numbers.”

Wagner Castings, a manufacturer that produced ductile-iron cast components for automakers and suppliers, opened in 1917 and was a major employer in Decatur for the next seven decades. Wagner Castings operated a 34-acre site and had as many as 1,000 employees in the city by 1990.

The Walker family planted roots in Decatur, and over the decades watched the town rise and fall. Walker’s father started his own business in 1981, at which Walker worked as a teenager, and took over 18 years ago.

“My dad was a very successful African-American business owner, all my life,” Walker said. “Back then in business in the ‘80s if you were in business you were successful, that’s what it equated to.”

“That was a time when money was plentiful. Everybody was working. Crime was down. You had factories … dad was working. Mom was working. Dad’s in the factory. Mom’s in the factory. They had checks coming from everywhere.”

By 2005, the former Wagner Castings site had closed its doors. The 34 acres once responsible for creating machinery, and wealth, was demolished and is now an Environmental Protection Agency cleanup site.

Other employers in Decatur have had similar stories. In 2001, after 38 years in the city, tire producer Firestone closed its doors. Large employers such as Tate & Lyle and ADM still maintain a huge presence, but even ADM made the decision to move its corporate headquarters to Chicago in 2013. More recently, Meda Pharmaceuticals announced plans to shutter its plant in 2018. Overall, the city has been experiencing a rough jobs climate: From December 2016 to December 2017, Decatur lost 700 jobs – a 1.4 percent decline – the second worst loss in the state, only behind Danville.

But even in a turbulent jobs climate, Walker – who owns a chauffeur business in Decatur – keeps perspective he’s developed from his family’s history and his personal experience in the community. More than two decades ago, Walker was arrested on drug charges and served four months in prison. But he rebounded, changed the trajectory of his life and has been a successful business owner, husband and father of four.

He credits his family, whose Decatur roots now extend over generations, with the support needed to get his life back on track to be productive for the community.

“I’m very thankful. I just come from great history, great roots,” Walker said. “My grandfather worked everyday for 39 years at Wagner Castings. Wagner Castings gave him an opportunity to take care of his family. The things that my grandfather was able to instill in my father … we have a strong work ethic.”

“I just want to be able to leave Decatur better than my grandfather left it for my father, and my father left it for me. And just Decatur being a better Decatur for my four boys.”

Dove, Gregory’s organization, is also focused on helping ex-offenders re-enter society and be productive. A hurdle in that effort, she says, is the natural struggle to forgive.

“We have a forgiveness problem … I think it’s hard for us as human beings to forgive,” Gregory said. “I think it’s hard for us to let the past go. And so you have to really work at it. You have to look at every single person as ‘they’re amazing, they have the potential to be amazing. And so what if they weren’t amazing yesterday, they can be amazing tomorrow.’”

Viewing an entire city through that lens – that it can be amazing tomorrow, even if it wasn’t amazing yesterday – might be just as difficult of a mentality, but it’s no less critical.

Thinking different

“People are definitely aware of [the population decline] and it’s been felt,” Peterson said. “Our retail market’s changed because of it and those jobs have been gone. At least two people that I know of [listed] their houses after the New Year and they’re looking at other states just to save themselves from [Illinois’] tax burden long term.”

In hindsight, the trend Peterson describes has been a long time coming.

But in advance of the 1990 Census, the population decline wasn’t seen in the same light. While that year marked Decatur’s first population dip after nearly a century of growth, the Soy City still held a degree of confidence.

Then-Mayor Gary K. Anderson said at the time that “the assumption should not be drawn that the loss is entirely tied to economic conditions.” He also said he expected the population to climb again between 1990-2000. It did not. Decatur’s population peaked in the 1980s, at just under 100,000 people. Today, it is under 75,000 people.

From January 1990 to January 2017, also, Decatur lost 2,000 jobs on net. The people still in Decatur are well aware of all of this. And while the state of Illinois continues on a downward path and city officials continue to squeeze every last dollar they can out of city taxpayers, residents are left thinking about what can be different.

“People are stuck in a rut,” Phillips said. “People who have been here a long time, they think about ‘hey we remember when Staley was here and big’ or [they talk about] ADM or Caterpillar. Caterpillar has grown and shrunk and grown and shrunk. Firestone’s gone completely. We need to start thinking outside the box to attract different kinds of businesses.”

Decatur has a rich history, tied in large part to the industrial strength of the region from the 20th century. But just like forgiving and providing second chances to individuals, being a place of opportunity again might mean adopting new mentalities – whether that’s for the state of Illinois, city officials, employers or job seekers. As Gregory said, she likes to think anyone can be “amazing tomorrow.”

“It’s all about saying ‘you know what, whatever happened in the past happened in the past and we need to move forward as a community,’” Gregory said. “We need to have hope. And we need to just be positive about what we can be, because we can be so much if we work at it.”

Have a story to share?

Tell us how a state or local policy affects your life.

If we decide to feature your story, one of our writers will reach out to you directly.