Springfield’s property tax levy swallowed by local pension costs

The Illinois Policy Institute recently published a study titled “The crisis hits home: Illinois’ local pension problem.” The audit measured 10 different metrics related to pensions to arrive at a holistic picture of how rising local pension costs are hurting each city’s fiscal health. The city of Springfield performed dismally in the audit. It scored...

The Illinois Policy Institute recently published a study titled “The crisis hits home: Illinois’ local pension problem.”

The audit measured 10 different metrics related to pensions to arrive at a holistic picture of how rising local pension costs are hurting each city’s fiscal health.

The city of Springfield performed dismally in the audit. It scored worst among the state’s 20 largest cities, and rising pension costs are now consuming every penny of the city’s general fund property tax revenues (those not already dedicated to items such as debt repayment).

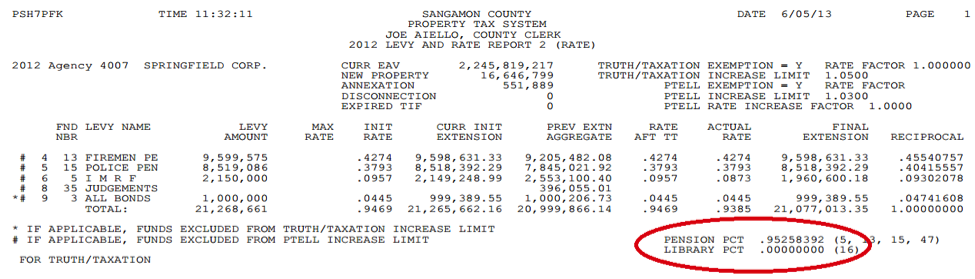

The city’s own 2012 Levy and Rate Report shows more than 95 percent of Springfield property tax levy goes to pensions. (In 2006, only 66 percent of the city’s $17.9 million levy went to pensions.)

But the report doesn’t capture all the pension costs for which Springfield is liable. The city is still paying off general obligation bonds that were used to fund pension costs related to early retirements.

In 2004, Springfield borrowed more than $15 million to pay the cost of early retirements for the city’s municipal employees to the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund, or IMRF. In fiscal year 2015 the bond repayment will total nearly $2 million.

Any repayment related to the city’s IMRF employees must also be added to the taxpayer cost of Springfield pensions.

The bottom line is this: the city’s general fund property taxes aren’t enough to pay for Springfield’s rising pension costs.

City services have been cut and sales taxes increased to make ends meet.

Since 2008, library branches have been shuttered and personnel reduced by 36 percent. Sworn police officers have been cut by 9 percent. Public work positions have been reduced by 26 percent.

Only through higher sales taxes has funding for sidewalk, sewer and street repairs been restored.

Unfortunately, despite higher taxpayer contributions, reduced city services and increased fees, city worker retirements are no more secure today than they were a decade ago. In fact, they are worse off.

The firefighter pension fund has less than 50 percent of the funds required to meet its future obligations. The police fund has just slightly more than 50 percent. In the private sector, these pension funds would be deemed bankrupt and closed immediately.

Some local officials don’t want to face the fact that out-of-control pension costs are hurting Springfield’s taxpayers and threatening the retirements of the city workers they represent.

Instead of actively working to address the crisis, they’d rather bury their heads in the sand.

But the city of Springfield, its taxpayers and its city workers cannot afford to wait. The municipal pension crisis grows larger every day.

Across the state, city officials are sounding the alarm on how rising local pension costs are hurting the fiscal health of their communities.

Our report gives a voice to their concerns. Our goal is to unite local city officials in their call for state-legislated municipal pension reforms

Springfield officials should join us.