Springfield couldn’t bail out Chicago Public Schools even if it wanted to

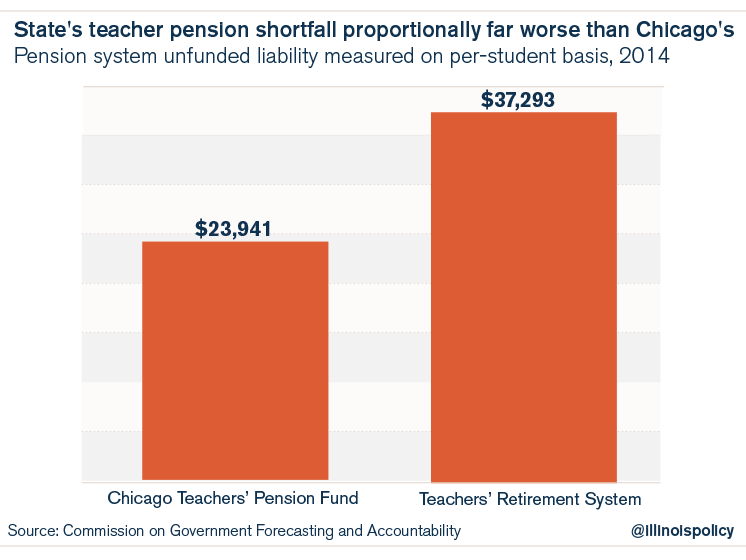

State-run teacher pensions have a shortfall of $37,000 per student, while Chicago's shortfall totals $24,000.

The Chicago Public Schools’, or CPS’, financial crisis has school officials and politicians – from CPS CEO Forrest Claypool to Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel to Chicago Teachers Union, or CTU, President Karen Lewis – calling for the state to bail out CPS.

CPS wants more money to patch over a fiscal nightmare that includes a $500 million hole in its fiscal year 2016 budget, a desperate $725 million bond sale, credit downgrades that have pushed the district deep into junk bond territory, and a looming teachers strike.

But even if Gov. Bruce Rauner and the Illinois General Assembly wanted to bail out CPS, they can’t. The state has an education crisis that’s arguably worse than Chicago’s.

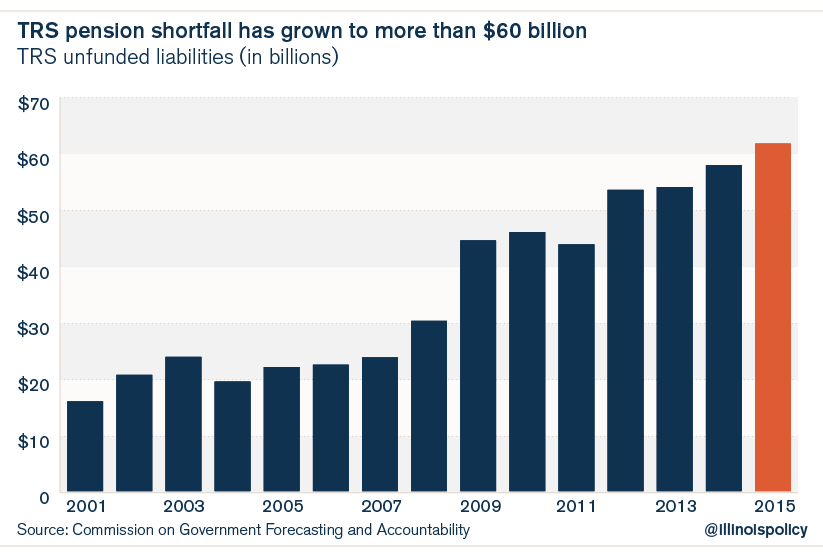

To start with, the Illinois Teachers’ Retirement System, or TRS, has a pension shortfall of nearly $62 billion. That dwarfs the pension shortfall for CPS, which is $9.5 billion.

In fact, when measured on a per-student basis – a better, apples-to-apples comparison – the state’s shortfall is 56 percent higher than Chicago’s. TRS has a short-fall of $37,000 per student, while Chicago’s shortfall totals just $24,000.

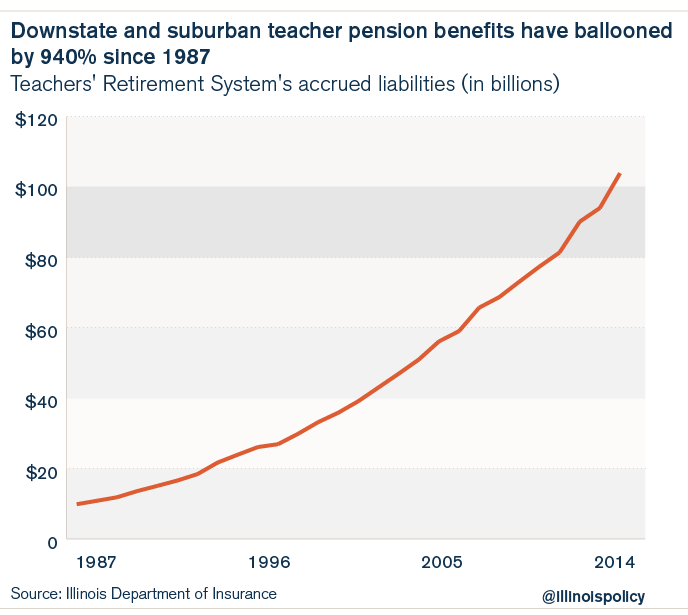

The state’s teacher pension-fund shortfall has been driven largely by the massive increase in pension benefits that teachers have accrued over the past decade. Teacher benefits have grown by 940 percent since 1987, a yearly growth rate of 9.1 percent.

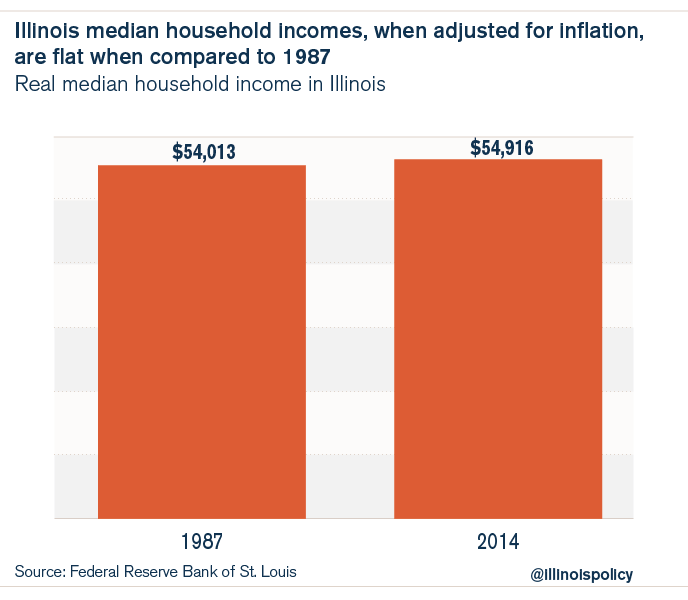

While pension underfunding often gets the lion’s share of the blame for the pension shortfall, the unsustainable growth of pension benefits deserves much attention. Teacher pension benefits have far outstripped the income growth of the Illinoisans who are required to pay for those benefits through higher taxes and reduced services.

In fact, Illinois median household incomes, when adjusted for inflation, are approximately the same as they were in 1987.

To pay for these benefits over the past decade, state officials have raided taxpayer funds dedicated to classrooms and used them to pay for old pension debt. It’s why today nearly 50 percent of the state’s education funding goes toward pensions. Only a decade ago, just 22 percent of the state’s education budget went to pensions.

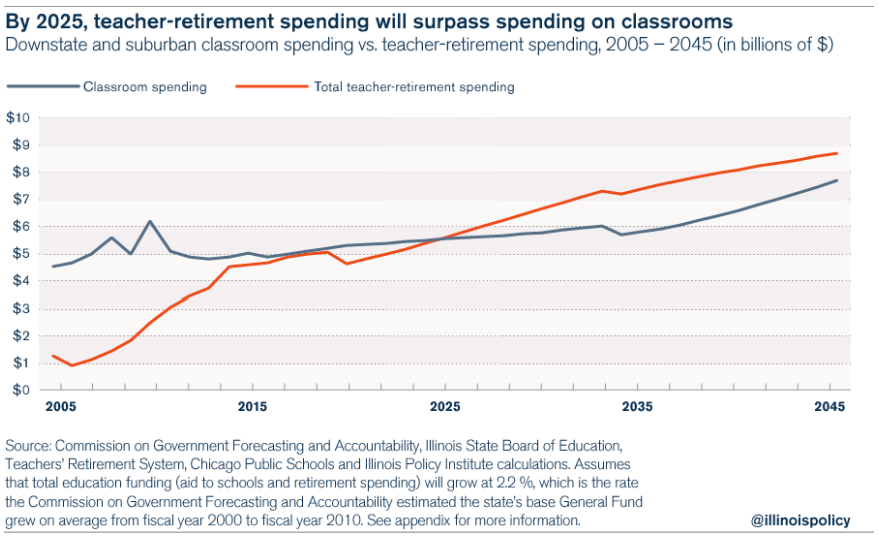

And by 2025, assuming the state’s pensions don’t worsen faster than predicted, the state will appropriate more for teacher pensions that it will for additional teachers, newer programs and new technology for learning.

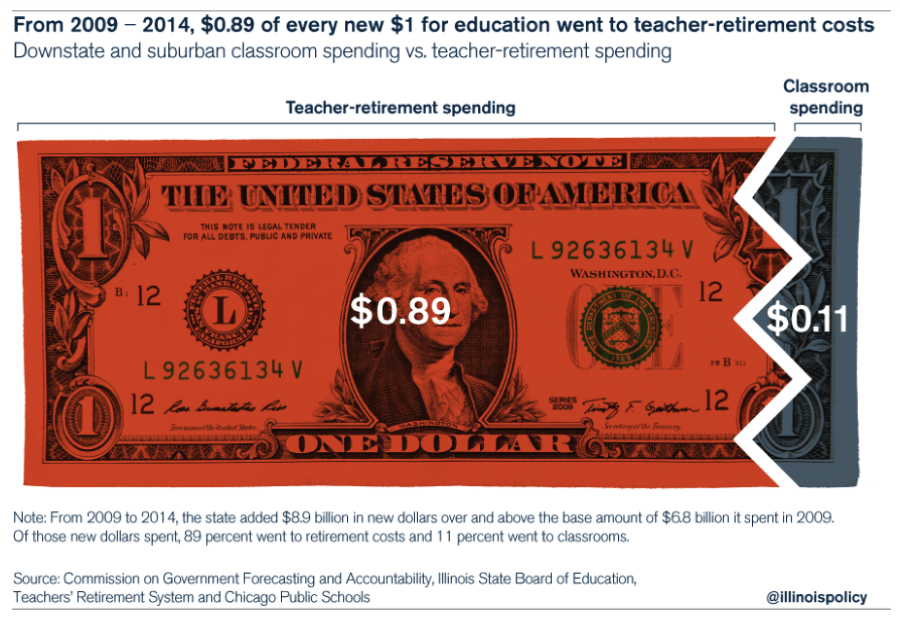

The last five years perfectly captures the pressure teacher pension costs are putting on state funding for classrooms. From 2009 to 2014, the state added $8.9 billion in additional education funding over and above what was spent in 2009. Of that amount, 89 cents of every dollar went to fund old pension debt. Only 11 cents went to fund actual education in the classroom.

Pension costs in Illinois are crowding out funding for the state’s core government services such as education.

Chicago may want a bailout from the state, but it should look elsewhere for a real fix to its problems.

Officials should start by opening up city contracts for renegotiation, right-sizing CPS payrolls, removing barriers to jobs growth in a flatlining city economy, and giving true security to new teachers in the form of 401(k)-style retirement plans. Those are a few of the politically difficult but necessary changes Chicagoans deserve.