Sangamon County homeowners: Where do your property taxes go?

Sangamon County billed homeowners $215 million in 2017. This meant owners of a $127,000 Springfield home had a $2,600 property tax bill.

Illinoisans pay some of the highest property taxes in the country. And those bills grew six times faster than household incomes from 2008 to 2015.

But where does all that money go?

In Sangamon County alone, property owners were billed for more than $324 million in property taxes in 2017, $215 million of which was for residential properties.

While the Sangamon County treasurer coordinates the collection of property taxes and processes property tax bills, those tax dollars don’t all stay with the county – the vast majority are distributed to other taxing districts within the county.

A property tax bill for a home in Springfield in Sangamon County shows where all those local tax dollars go.

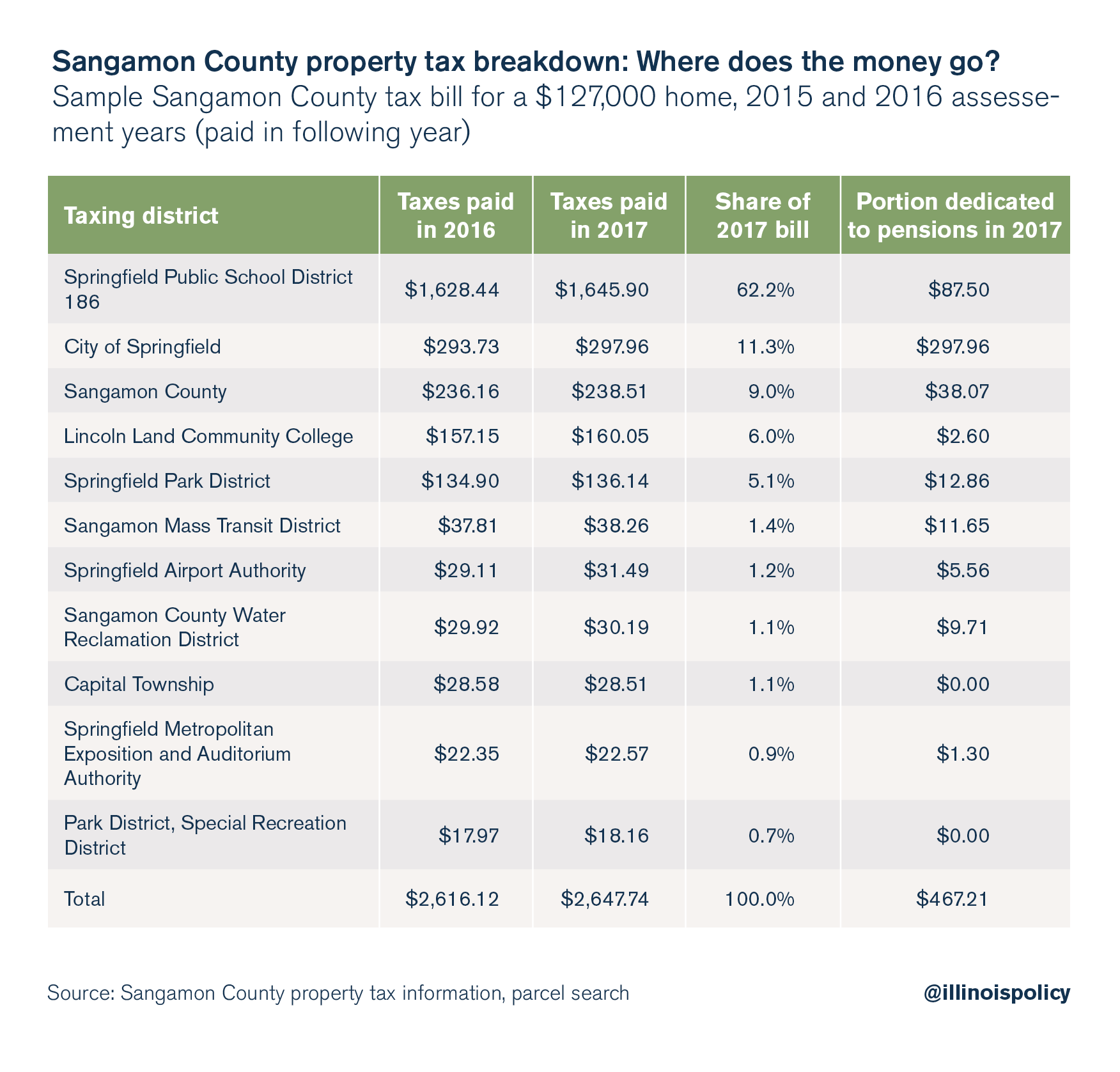

Take a house that might sell for around $127,000 – slightly above the median home value in Springfield, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.1 The property tax bill on this house would have totaled more than $2,600 in 2017. Ten different local government units would have received some of those property tax dollars, including entities such as Springfield Public School District 186, Lincoln Land Community College, the city of Springfield and the Springfield Park District. (Interestingly, the Springfield Park District levies two separate property taxes, both of which would apply to this home.)

Nearly 18 percent of the homeowner’s property tax bill went to government workers’ pension funds, amounting to $467 in 2017. The entire amount taken by the city of Springfield – nearly $300 – went to pensions.

And of the $2,600 in taxes paid in 2017, $1,645, or 62 percent, went to Springfield Public School District 186.

In the 2015-2016 school year, local property taxes made up $105 million, or more than 56 percent of the $187 million in total revenue that District 186 took in, according to the district report card published by the Illinois State Board of Education.

In that year, District 186 spent a total of $188 million, of which nearly half went toward instruction, 36 percent funded supporting services (e.g., student health services, professional development for teachers, guidance counseling, etc.), 3 percent paid for general administration, and 11 percent funded other expenditures, such as capital outlays and maintenance. The average teacher salary in District 186 in 2016 was $60,311, and the average administrator salary was $100,996.

District 186 voted to raise its property tax levy 3.3 percent for 2018, according to WRSP.

With more than 6,000 local taxing districts that levy property taxes, hefty government payrolls and high administrative costs in schools – which receive the largest share of property taxes – Illinois homeowners and businesses bear a heavy burden.

Unfortunately, county and municipal officials’ hands are tied with respect to some of the most significant drivers of the cost of local government – and therefore, property taxes.

The state’s unfair collective bargaining laws have tilted the tables toward government worker unions and led to expensive contracts for which taxpayers have to foot the bill.

And Illinois’ pension laws, combined with unaffordable benefits for government workers, have led to more and more property tax dollars flowing to increasingly indebted pension funds rather than toward essential services. Illinois’ total local pension debt increased more than 48 percent between 2010 and 2016, climbing to nearly $57 billion.

Many local governments have resorted to raising property tax levies to cover pension payments.

And Springfield is no stranger to pension woes. The city’s director of the Office of Budget and Management has projected that the city will spend about $600,000 more on its police and fire pension payments than it will collect in property taxes during the upcoming budget year, the Springfield Journal-Register reported.

Sangamon County residents, such as those in Springfield, must look to state lawmakers to enact reforms that will provide relief from high property taxes and bring government costs down to a level taxpayers can afford. That means, at the very least, freezing local property taxes as a first step and enacting real pension reform, prevailing wage reform and collective bargaining reform.

Until that happens, Sangamon County homeowners will be stuck paying painfully high property taxes.

1Value estimates by township assessors lag actual market prices, so the property tax bill on a home that might sell for close to $127,000 could have a “fair market value,” or assessor’s estimated market value, of $113,000.