Why the 2017 tax hikes will harm Illinois’ economy

By Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill, Joe Tabor

In 2017, the Illinois General Assembly passed a 32 percent income tax hike, the largest permanent income tax hike in Illinois history. Lawmakers hiked the personal income tax to 4.95 percent from 3.75 percent and the corporate income tax to 7 percent from 5.25 percent.

The plan aimed to raise an additional $5 billion in income tax revenue from Illinois taxpayers. But that wasn’t its only cost. The income tax hike will also hurt the state’s already-sluggish economy.

How can Illinoisans be sure the 2017 tax hikes will harm the state’s economy? Because they’re still feeling the effects of the same misguided policy choice from 2011.

Most economists agree that when lawmakers raise taxes economic growth suffers because of the negative impact of higher taxes on investment. This was the case with Illinois’ 2011 tax hike, and will be the case with the most recent tax hike as well.

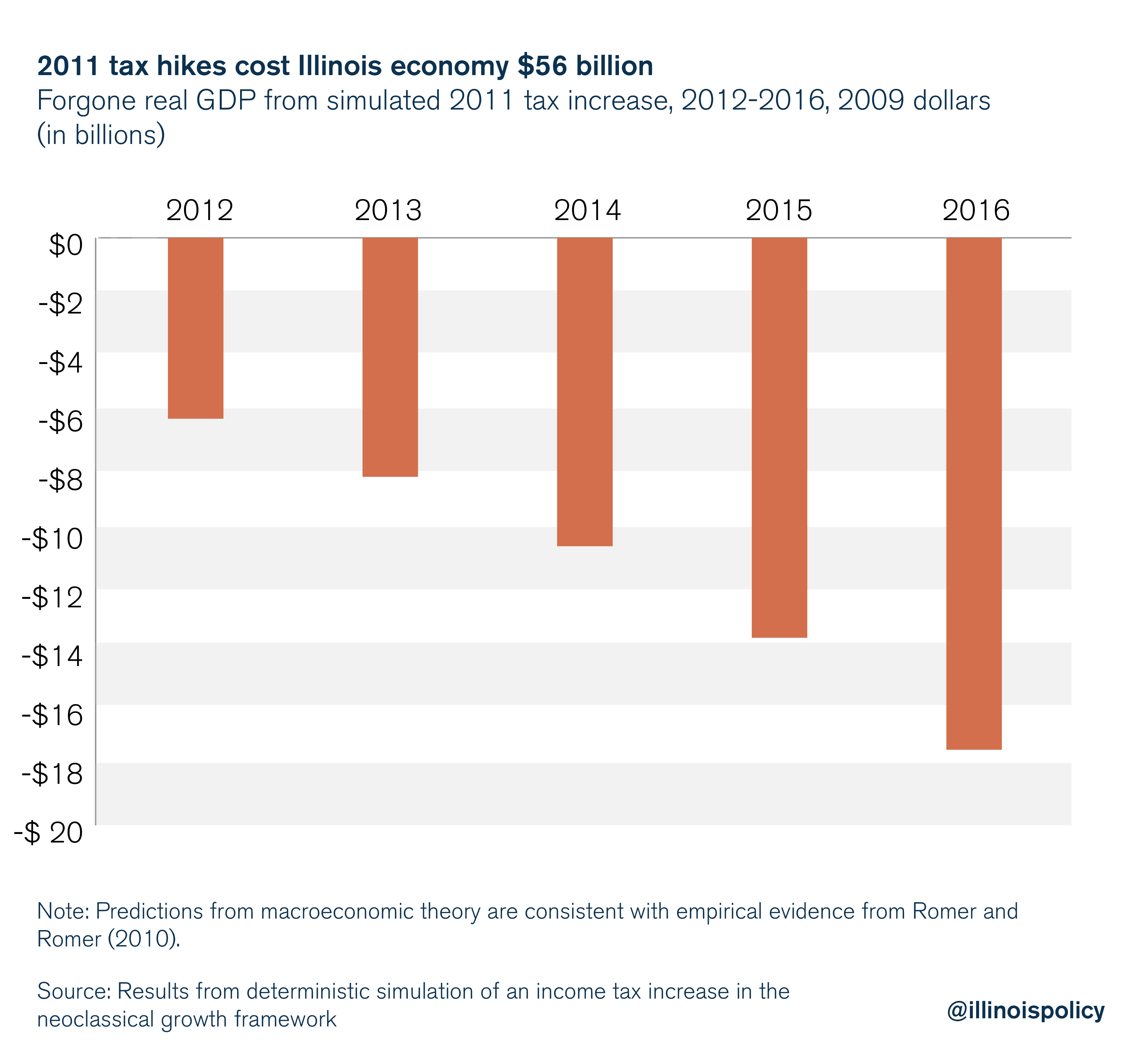

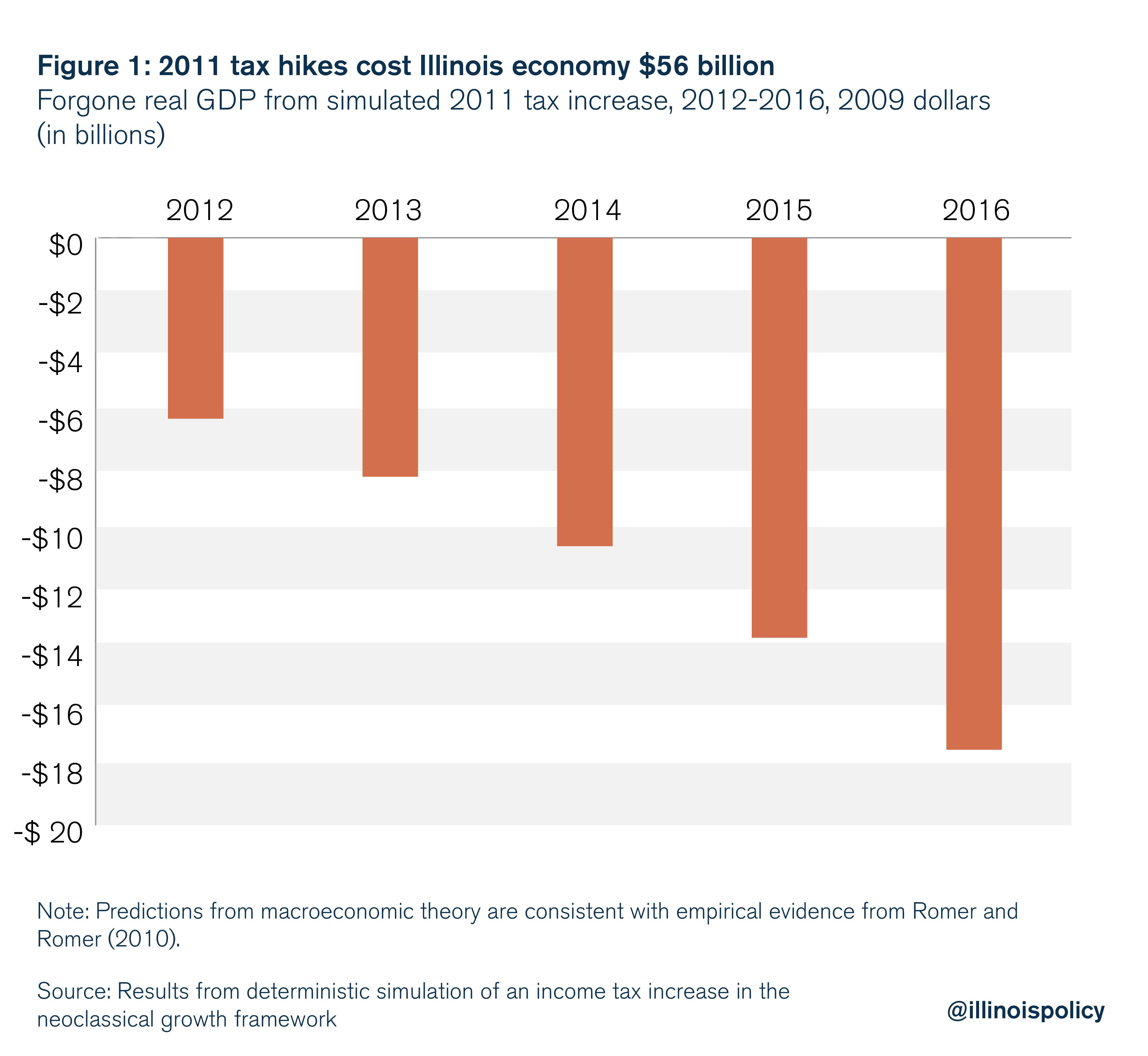

Illinois Policy Institute analysis estimates that while the 2011 tax hike raised $31 billion in additional revenues, it cost the state $24.8 billion in gross output, or real GDP, during the tax hike years (2012-2014). Unfortunately, due to the tax hike’s drag on investment, its economic harm extends beyond its partial sunset at the beginning of 2015. The Institute estimates the 2011 tax hikes cost the state economy $55.8 billion in real GDP from 2012-2016.

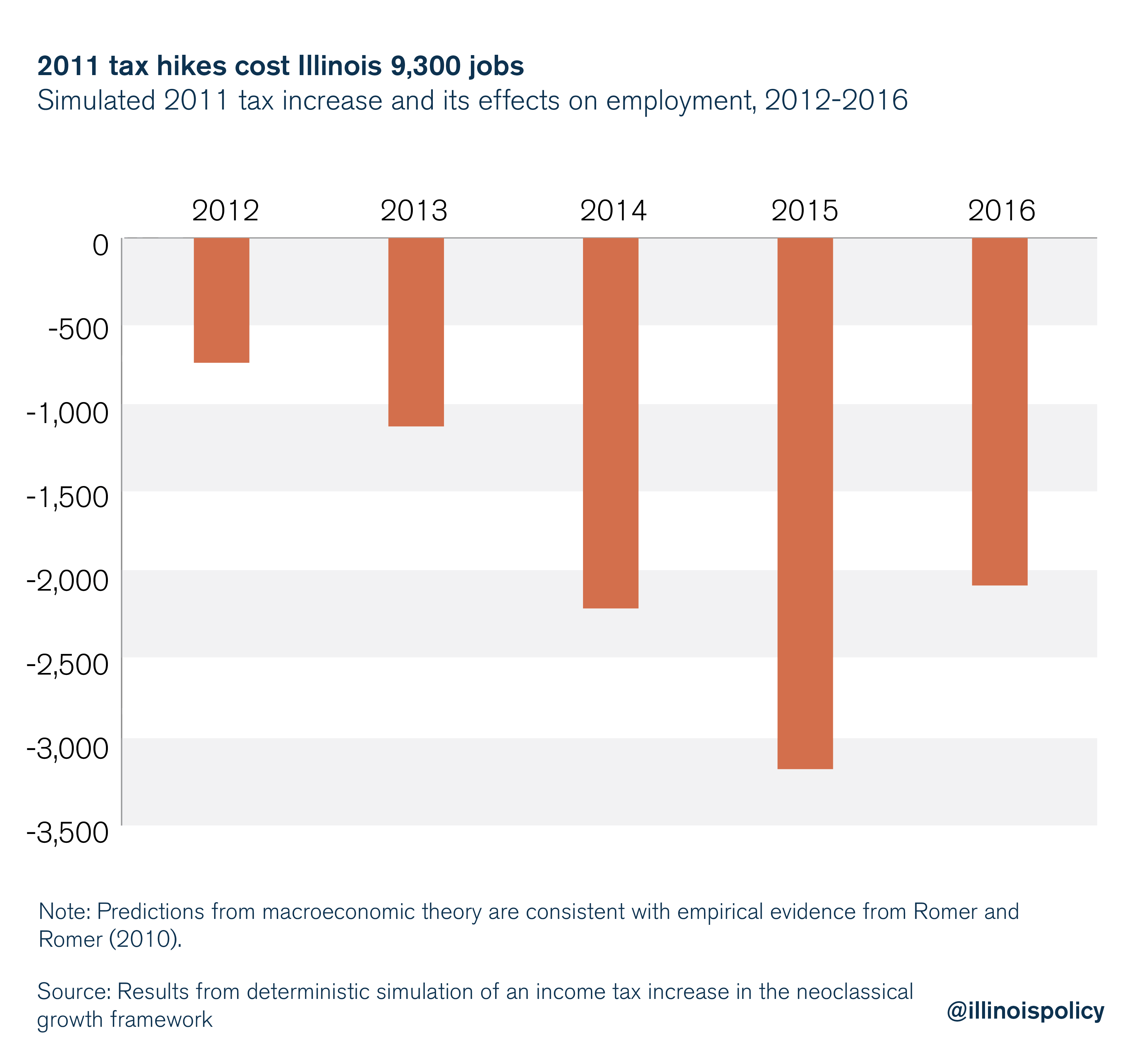

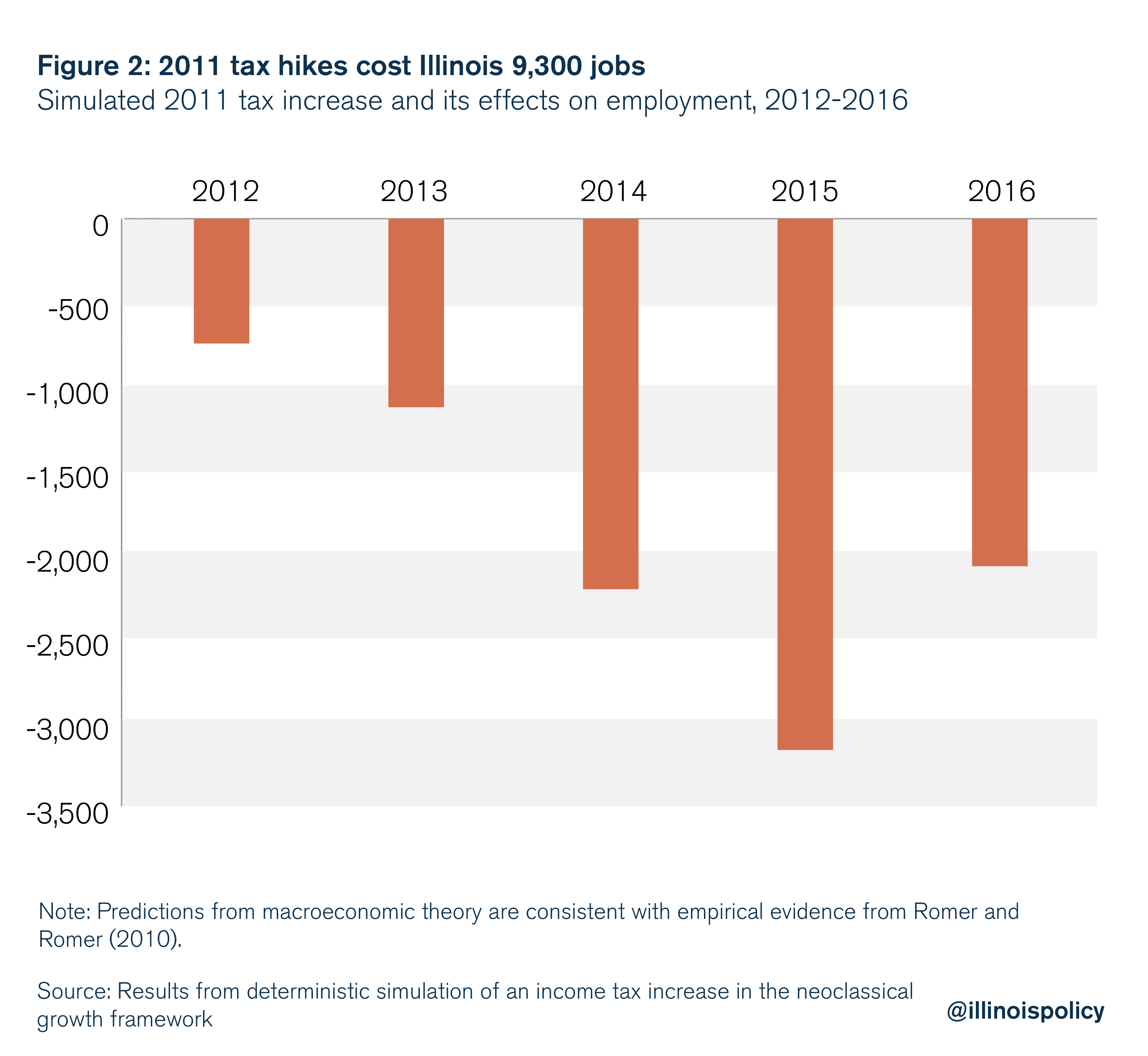

This economic cost consists of a reduction in not just the number of jobs in Illinois, but also in the quality of those jobs. The tax hike decreased employment by 9,300 jobs between 2012 and 2016, and caused output per worker to decline by $7,200. Even after its partial sunset, the 2011 tax hikes continue to have negative economic effects today.

Unfortunately, the 2017 tax hikes will have similar negative effects, and the increase in revenue cannot justify the long-term economic cost. The tax-and-spend approach is shortsighted because it will harm Illinois families in the long term.

Introduction

When confronted with the decision to cut or to raise taxes, lawmakers field questions such as: To what extent does a tax cut pay for itself? Or in the case of a tax hike: How much additional revenue will it yield?

Traditional revenue estimation, called static scoring, assumes no impact of taxes on economic activity. The other extreme suggests that tax cuts can generate so much economic growth they can completely pay for themselves. Most experts are skeptical of both extreme cases. Most economists agree that taxes have an influence on aggregate income, but the magnitude of the effect is still open for debate.

The Illinois Policy Institute’s analysis of the 2011 tax hikes is closely related to Mankiw and Weinzierl (2006),1 who provided an example of dynamic scoring using standard macroeconomic models. The analysis is also related to Prescott (2004),2 who raised the issue of the incentive effects of taxes by comparing the effects of taxes on labor supply in the U.S. and European countries.

What is the evidence on the effects of taxation?

Measuring the effects of tax changes on the economy is a challenging task. This is because it is difficult to distinguish movements in fiscal variables caused by tax policy shocks from those that are simply the automatic movements of fiscal variables in response to other economic shocks – normal aggregate fluctuations in economic activity or monetary policy shocks. There is also the fact that even the announcement of a tax change alone can cause responses in economic activity.

Fortunately, there is a large body of expert literature that addresses these difficult empirical challenges and proposes economic theories that are consistent with the evidence.

Economists distinguish between two types of tax changes. Endogenous tax changes are taken to offset economic developments that would cause output growth to deviate from normal, and exogenous tax changes are not motivated by changes in output growth away from normal.

An example of an endogenous tax cut is one that is implemented when a recession is forecasted. In order to prevent a steep contraction in economic activity, lawmakers may resort to expansionary fiscal policy such as a tax cut. This is a tax change that is taken in response to observed or anticipated economic activity.

On the other hand, an example of an exogenous tax change is Illinois’ recent tax increases. The tax increases were not motivated by a deviation in output growth away from normal growth. The tax increases were motivated by inherited budget deficits. An inherited deficit reflects past economic and budgetary decisions, not current spending changes or current economic conditions. Tax hikes to deal with Illinois’ fiscal crisis are not changes motivated by a desire to return growth to normal or to prevent abnormal growth.

Romer and Romer (2010)3 find that exogenous tax increases have a negative impact on real gross domestic product. The maximum effect of a tax increase equivalent to 1 percent of GDP is a fall in output by almost 3 percent after 10 quarters. Tax increases have a very large and sustained, negative impact on output. Romer and Romer’s research also points out that tax increases motivated by inherited deficits are less costly than other tax increases if these tax increases are accompanied by spending cuts. This is due to the impact on expectations and on long-term interest rates.

To understand why output declines, Romer and Romer (2010) find that a tax increase equal to 1 percent of GDP leads to a 2.55 percent fall in personal consumption expenditures and an 11.19 percent fall in gross private investment.

These results are consistent with the findings of Blanchard and Perotti (2002)4 and Mountford and Uhlig (2009).5 Investment falls in response to both tax increases and government spending increases.

What a tax increase means for Illinois

Taking these findings seriously, this analysis borrows a macroeconomic model from the expert economics literature because the model economy behaves similarly to the real economy. The model is based on neoclassical theory, which is among the most widely used tools for research in macroeconomics. A full description of the model is included in Appendix A.

The 2011 tax increase raised approximately $31 billion between 2011 and 2015. Income tax as a share of gross state product increased to 3.1 percent from 2.6 percent, a change of 0.5 percentage points.

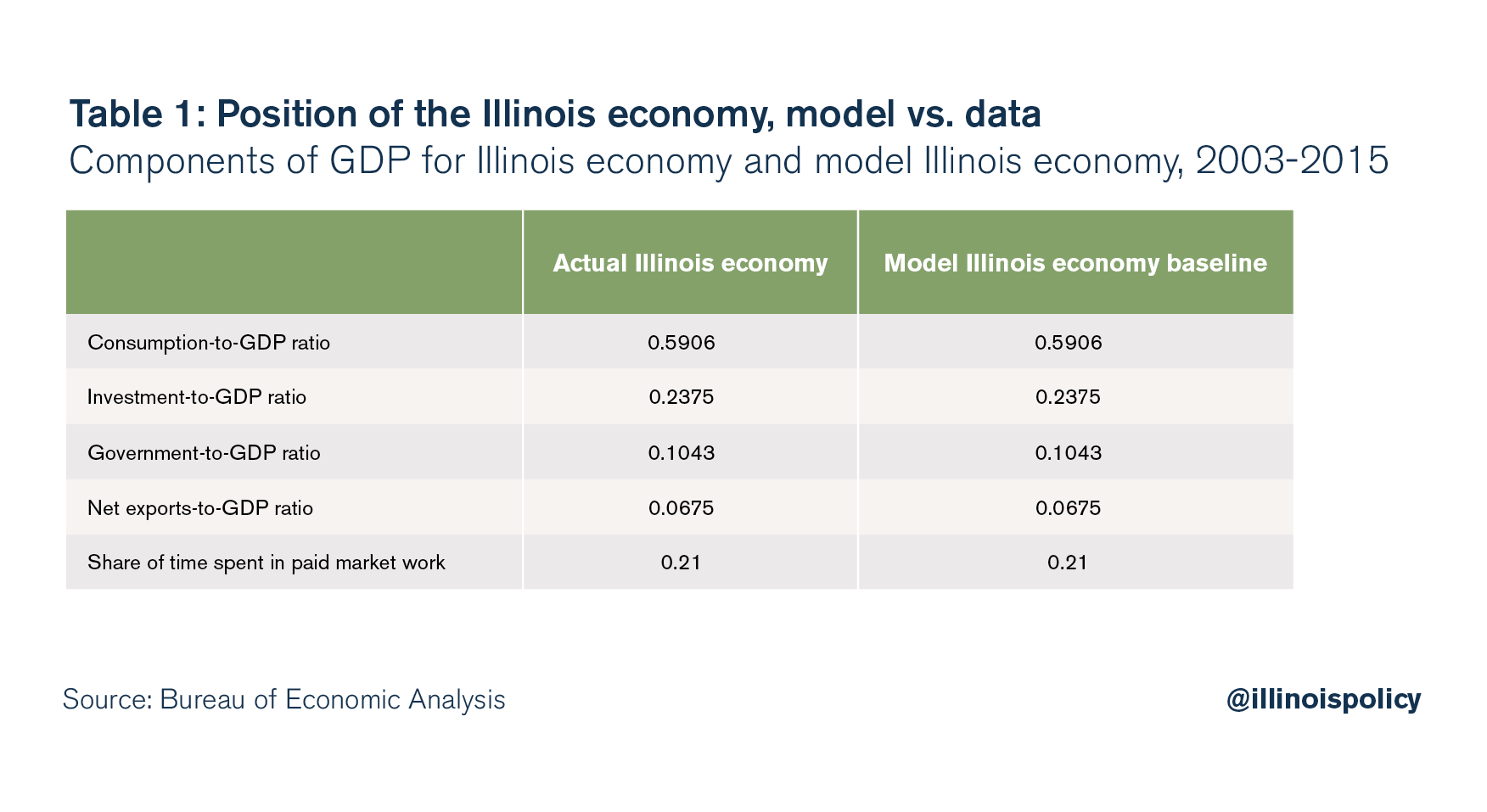

Table 1 compares the average long-run position of the Illinois economy with the calibrated model economy, illustrating the model’s ability to match the long-run average position of the Illinois economy.

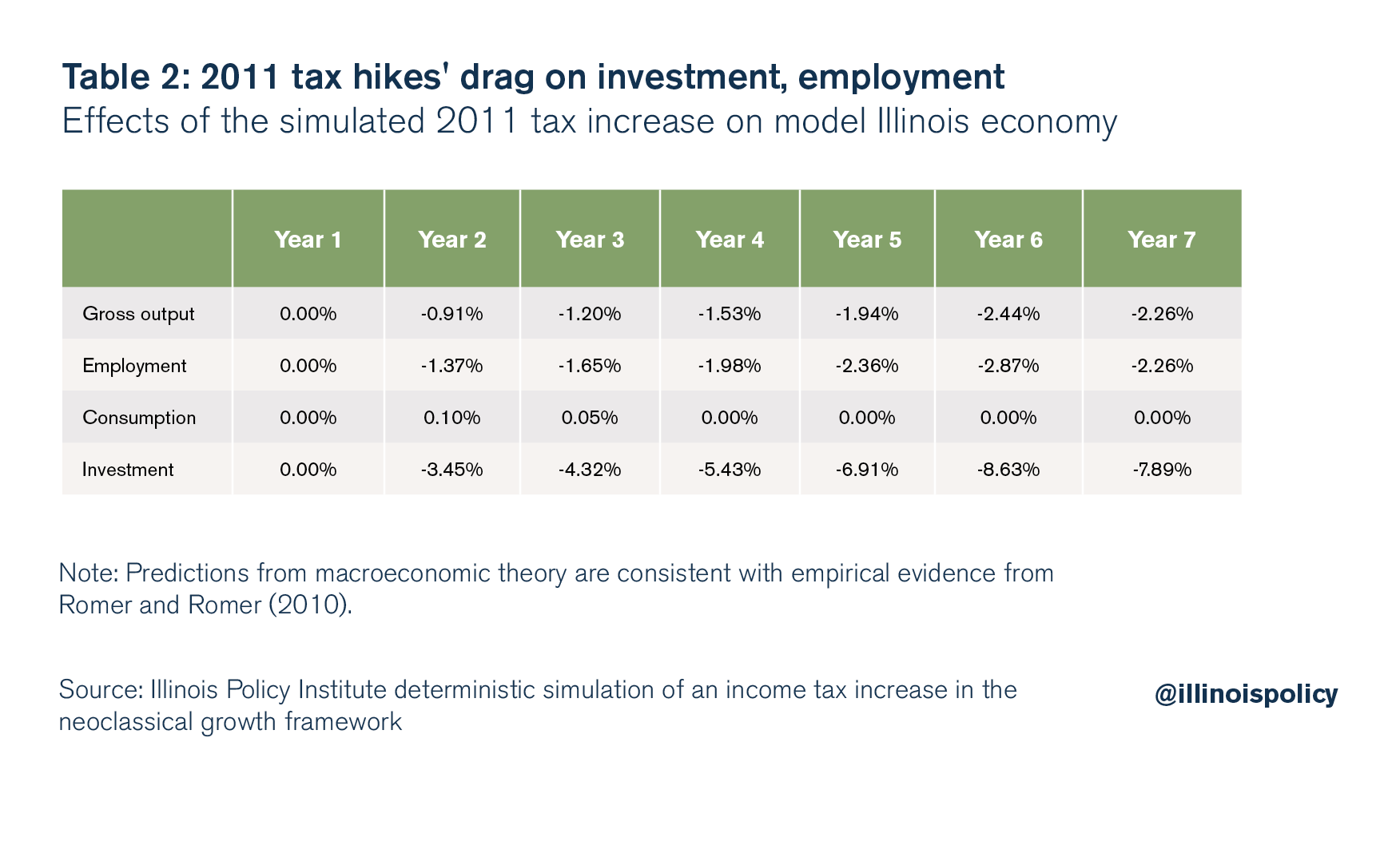

Table 2 reports the neoclassical growth model’s predictions for the effects of an increase in the income tax burden that is consistent with the 2011 temporary income tax increase.

The results are consistent with empirical evidence on the effects of taxation. A tax increase has a negative effect on gross economic output. This is caused by a large and persistent decline in investment, while the responsiveness of consumption to the tax change is negligible.

The 2011 temporary tax increase has lasting negative effects on the economy that stretch beyond the partial sunset in 2015. This is because capital accumulation takes time, and a slowdown in the growth rate of productive capital means the effects of the tax hike will be felt long after any improvements in the tax climate.

In all, while the 2011 tax hike raised $31 billion in additional revenues, it cost the state $24.8 billion in gross output, or real GDP, during the tax hike years (2012-2014). Unfortunately, due to the tax hike’s drag on investment, its economic harm extends beyond its partial sunset at the beginning of 2015. The Institute estimates the 2011 tax hikes cost the state economy $55.8 billion in real GDP from 2012-2016.

This economic cost consists of a reduction in not just the number of jobs in Illinois, but also in the quality of those jobs. The tax hike decreased employment by 9,300 jobs between 2012 and 2016, and caused output per worker to decline by $7,200. Even after its partial sunset, the 2011 tax hikes continue to have negative economic effects today.

The 2017 tax increase is expected to have similar negative effects on Illinois’ economy.

This is part two of a two-part series on Illinois’ struggling state economy. Click here to view part one: “What’s dragging down Illinois’ economy?”

Endnotes

- Mankiw, N. Gregory, and Matthew Weinzierl. “Dynamic Scoring: A Back-of-the- Envelope Guide,” Journal of Public Economics 90 (8-9, Sep)(2006): 1415-1433.

- Prescott, Edward C. “Why Do Americans Work So Much More than Europeans?” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review 28, no. 1 (July 2004): 2–15.

- Romer, Christina D., and David H. Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks,” American Economic Review 100, no. 3 (June 2010): 763-801.

- Blanchard, O., and R. Perotti, “An Empirical Characterization of the Dynamic Effects of Changes in Government Spending and Taxes on Output,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 117, no. 4 (2002): 1329–1368.

- Mountford, A., and H. Uhlig, “What Are the Effects of Fiscal Policy Shocks?” Journal of Applied Econometrics 24, no. 6 (2009): 960-992.