Saint

Some people call Julie McCabe-Sterr their Mother Teresa.

She’s a three-time cancer survivor who has chaired her local Relay For Life fundraiser five times. The back seat of her car once held a young man dying of a heroin overdose as she drove to find help. And for more than a decade, McCabe-Sterr has shepherded hundreds of addicts through her county’s groundbreaking drug-court program.

For 18 months, drug-court participants meet weekly in a dimly lit room in the basement of the Will County State’s Attorney’s Office in Joliet, Illinois. They receive treatment, counseling and support from McCabe-Sterr and her team.

In the northwest corner of the room, McCabe-Sterr installed a floor-to-ceiling poster of a tropical view — with matching curtains — to cover a door to a safe. The building once housed a bank. The safe is now used to store police evidence.

“We needed to brighten things up a bit down here,” she said.

On graduation day, weeping mothers shower McCabe-Sterr with gifts. And drug-court graduates hug their loved ones, some for the first time in years.

Graduation can be a scary time for many in the drug-court program, McCabe-Sterr said. The responsibilities and opportunities of a life of sobriety can seem daunting.

But after a year and a half of hard work, McCabe-Sterr knows they’re ready. And she has the data to prove it.

The power of drug court

Illinois is home to a recidivism crisis.

Within three years of their release from prison, over 45 percent of offenders will return to life behind bars – each instance of recidivism costing taxpayers more than $40,000 per offender in court, arrest and prison costs, according to research by the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council.

But programs that trade prison stints for the tough love of rehabilitation have proven powerful enough to break this cycle.

Alternative sentencing efforts such as drug court – which put individuals convicted of crimes due to drug abuse on strict treatment regimens, rather than handing down prison time and saddling them with felony records – are turning out healthy members of society at a fraction of the cost of housing inmates and awaiting their likely return after release.

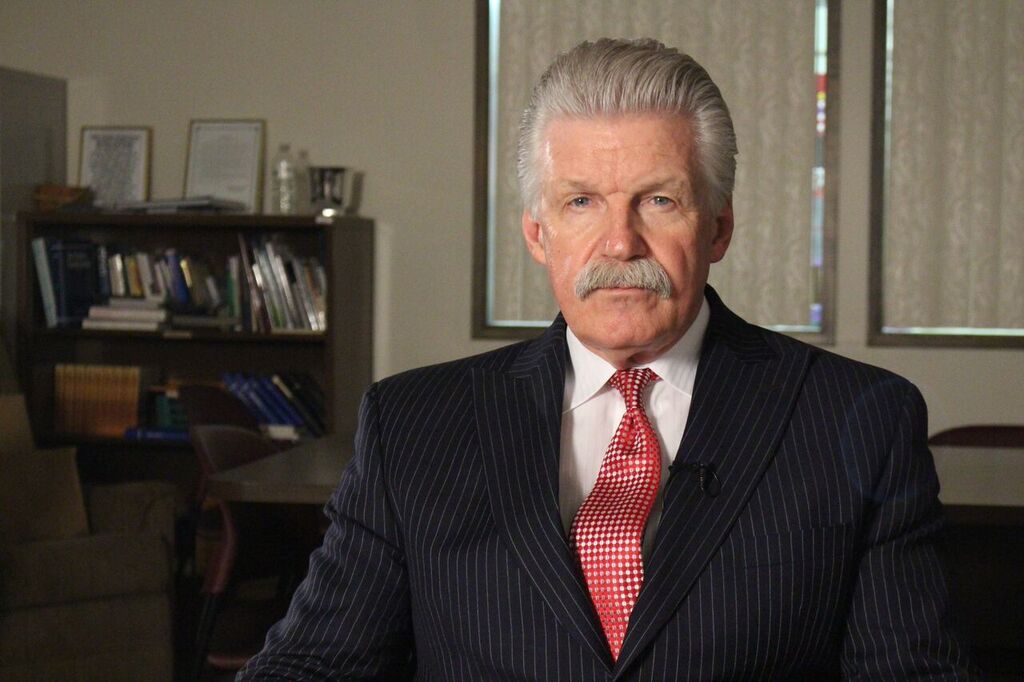

Will County State’s Attorney James Glasgow made international headlines in 2012 for obtaining a murder conviction against former Chicago-area police officer, Drew Peterson. He’s also a champion of this type of alternative sentencing, overseeing the Will County mental health court, veterans court and drug court.

Since Glasgow lead the establishment of Will County’s drug-court program in 2000, less than 10 percent of graduates have reoffended, according to his office. The cost of putting more than 300 graduates through the program? About $3,000 each.

Meanwhile, the Illinois Department of Corrections pays nearly $22,000 in direct costs per inmate – add up employee health care, benefits, pensions and capital expenses, and the cost per inmate is nearly $40,000.

“We found a tool that works and we’re using it aggressively, ” Glasgow said.

“Because of the heroin problem the way it is, because of the fatal nature of the drug, it’s critical that these individuals get into drug court not just to avoid prison, not just to avoid a felony conviction, but to stay alive.

“And we’ve proven we can do that.”

These aren’t empty words from Glasgow. Just ask Kristin Love, a 2013 drug-court graduate.

Redemption

Growing up just outside Joliet, Love was a promising student from a well-to-do family. But at 16, when she tried heroin for the first time at a party, she knew she was hooked.

Six years later, a drug bust led to her arrest in a McDonald’s parking lot.

“My parents, my family, my significant other, nobody knew,” Love said of her addiction. “They might have had suspicions, but nobody knew until I called them from jail.”

Before her trial, Love’s family pleaded with her to opt in to drug court. Love was skeptical.

“I think for a lot of people addicted to drugs, they just want the easy way out,” Love said. “So I thought, well, maybe I could do a little time in jail and be done, then I could go back to what I was doing before.”

But Love eventually agreed to her family’s wishes and flourished in the Will County drug-court program. She received treatment, did volunteer work, returned to school, and landed a job – her first.

“I think the longer I did those things, the more I built better feelings about myself – more confidence – and drugs weren’t so important anymore,” she said.

Without a felony on her record, Love pursued legal studies after graduating from drug court, and now works as a legal secretary for the very people who prosecuted her for drug possession – in the Will County State’s Attorney’s Office.

Glasgow came to her interview.

“Finding out … I was getting the job, I think I cried,” Love said. “It was one of my favorite days.”

Renewal

Illinois Gov. Bruce Rauner set a goal of reducing the state’s prison population by 25 percent come 2025. This won’t happen without major reform.

But programs such as drug court are proving that policymakers don’t have to choose between cost cutting and better outcomes when it comes to criminal justice. Moreover, that reform doesn’t need to come at the expense of public safety.

“People do life in increments in [the Department of Corrections],” McCabe-Sterr said.

“Isn’t it more important that we can continue to give them the skills and the support they need so they don’t go back and do that?”

For thousands of Illinoisans who have made poor choices in the past, preventing the destruction of their futures means expanding drug and mental health treatment programs such as those that have been successful in Will County, as well as increasing the availability of sealing and expungement of criminal records after ex-offenders have served time.

Perhaps more than anything, drug courts show the value of sealing and expunging criminal records for ex-offenders who have proven records of rehabilitation. Sealing a record means it can only be seen by law-enforcement agencies. Expungement means one’s record is wiped clean.

Currently in Illinois, only offenders convicted of nonviolent, low-level felonies may apply for record sealing. They also must endure a waiting period of three to four years before they file petitions to have their records sealed with the courts that sentenced them.

Long waiting periods during which ex-offenders bear the scarlet letter of a felony record pose a serious public-safety risk. Employment is one of the most important factors in keeping ex-offenders from re-entering the criminal-justice system.

“I was really worried about that,” Love said of the prospect of a felony record when she was arrested.

“At the time, I was in college, and I just thought, ‘If I’m going to have a felony, what’s the point?’”

In short, narrow focus on a purely punitive, rather than rehabilitative, criminal-justice system reinforces the cycle of crime that Glasgow and other law-enforcement officials have been trying for decades to halt.

He says Illinoisans simply can’t afford more of the same.

“It’s going to bankrupt us, and I think we see that,” Glasgow said.

“[But] compassion is the key to turning the corner.”