When Illinois home values fall, but property taxes don’t

By Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill, Joe Tabor

If an Illinois worker takes a pay cut during a recession, she knows the state isn’t going to take an even bigger chunk out of her paycheck. That’s because the state income tax rate stays the same.

But if her home loses value, too, she could still see her property tax bill go up.

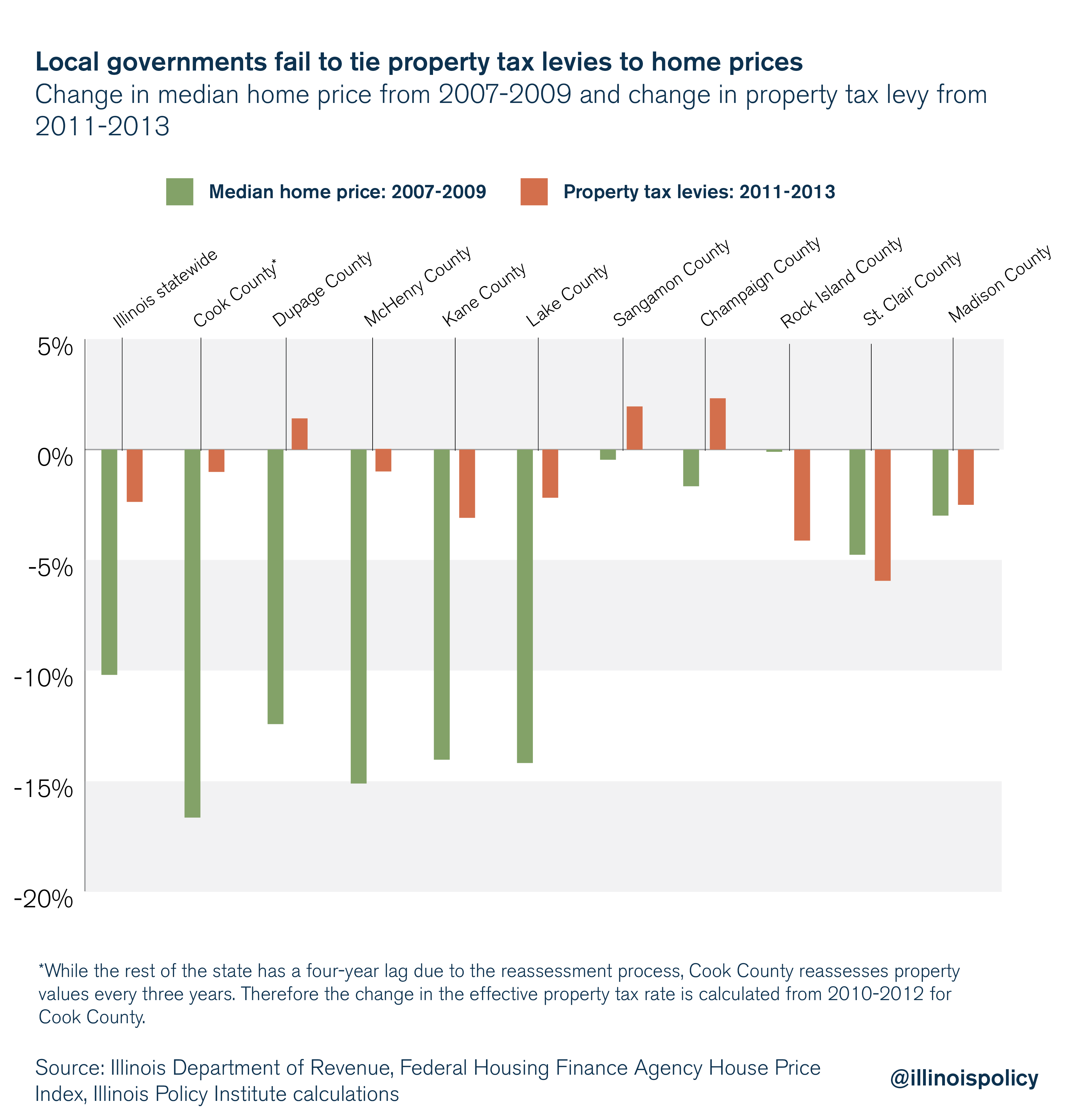

Government data show that despite falling home prices during the Great Recession, local governments across the state failed to adequately reduce property tax levies on a shrinking tax base, leading to higher – not lower – property tax burdens.

From 2007-2009, the worst years of the Great Recession, home values fell by 10.2 percent in Illinois. That means residents would expect property tax bills to decline by the same amount from 2011-2013, due to the four-year lag in the assessment process. Instead, property tax bills only fell by 2.4 percent during that time.

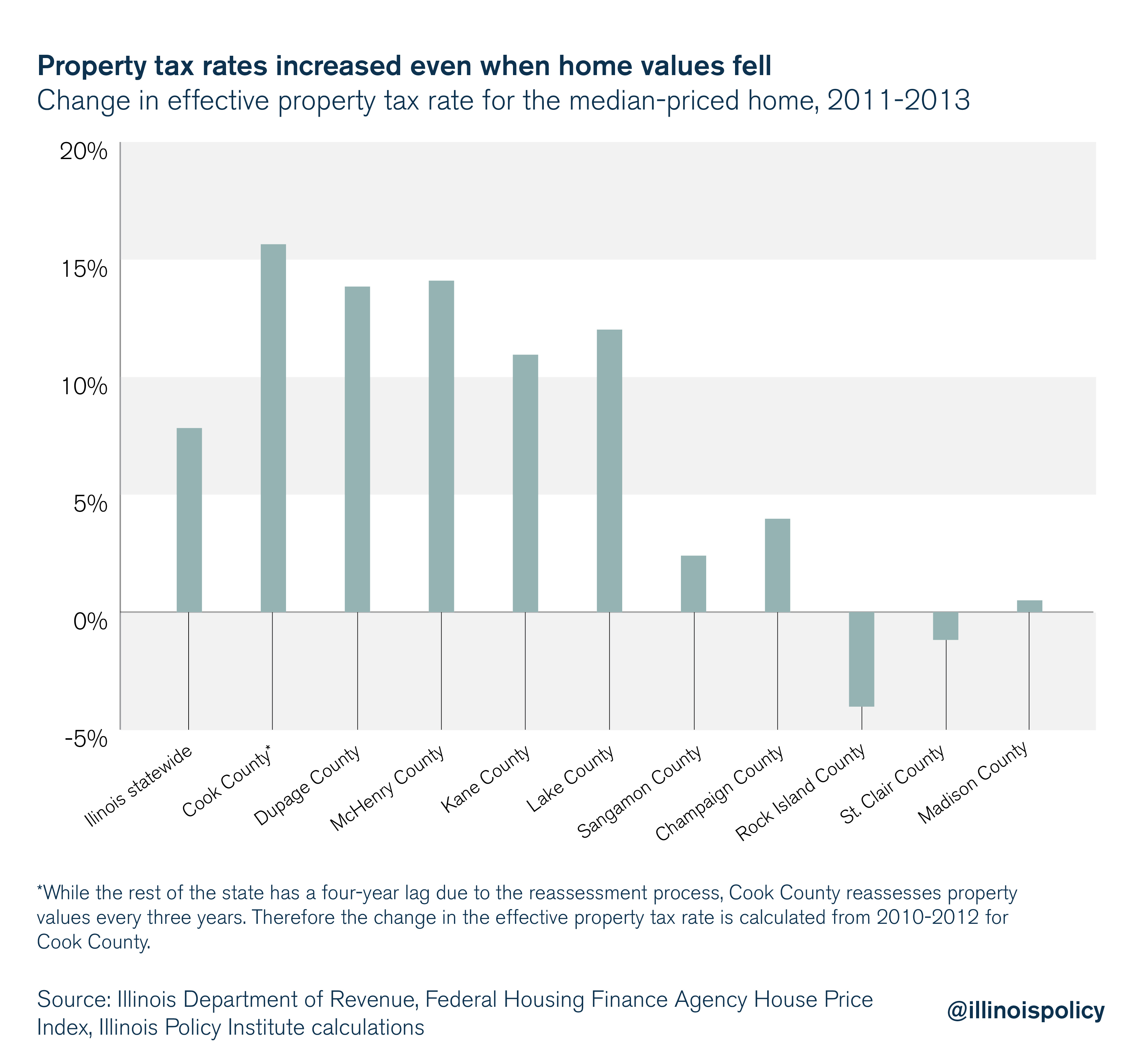

That means property tax rates – the property tax bill as a percent of a home’s value – increased by 7.8 percent.

In many areas, homeowners saw their property tax bills go up despite falling home prices.

For example, in DuPage County, home values fell 12.4 percent from 2007-2009. But local governments more than offset the expected decline in property tax revenues that would have resulted from declining home values. How? By jacking up the property tax burden.

Property tax revenues in DuPage County increased by 1.4 percent from 2011-2013. That means property tax rates saw a 13.9 percent increase over the same time.

This rapid increase in the tax rate meant the median homeowner in DuPage County was fleeced for an additional $812 on his property tax bill in 2013 compared to 2011, even though the home he had invested in had lost value.

It wasn’t just DuPage. Counties across Illinois faced higher property tax rates despite a decline in housing prices.

Although families throughout the state were finding it harder and harder to make ends meet, local governments refused to provide them with any reprieve from their property tax burden. In fact, most places saw an increase in their property tax rates.

Property tax rates increase even when home values are decreasing

Due to the relatively infrequent nature of housing assessments, changes in property tax revenues should lag changes in home prices. In Illinois, home values are assessed every four years – with the exception of Cook County, where home values are assessed every three years. That means that if home values fall by 1 percent, tax revenues should also fall by 1 percent in the years that follow the decline in home values.

Because of the assessment process that doesn’t correct for fluctuations in market conditions, economic research finds that changes to property tax rates lag changes in the price of homes by three to five years. That means when home values decrease, homeowners get no immediate tax relief. In Illinois, even when a new assessment reveals a decline in home values, rates continue to increase.

When families lose money on their biggest investment, lawmakers still bill them according to the price of their homes before the downswing. Similarly, during the recovery, while homes are still assessed at their recession level, lawmakers continue to raise tax levies to generate their desired tax revenue.

Property taxes are supposed to align the interests of homeowners with those of local governments. If property values go up, so too should tax revenues. And if property values go down, local governments have to tighten their belts. But that’s not what happens in Illinois.

Illinois needs property tax reform

Illinoisans pay some of the highest property taxes in the nation.

Further, the current system is indifferent to the suffering that families experience during an economic crisis. These families are rapidly losing wealth while still being crushed by an enormous property tax burden.

In recessions, while incomes fall and home prices fall, property tax levies do not do so in tandem. In fact, the levies often increase. One possible way to fix the current system would be to increase the frequency of property tax assessments and to require a freeze on property tax levies.

Even with more frequent assessments, it’s not clear that local governments would get their spending in order. Too often, even local leaders who want to cut property taxes are handcuffed by decisions at the state level that drive up the cost of local government. At the state level, a property tax freeze, coupled with aggressive government consolidation efforts and reforms to pensions, collective bargaining and workers’ compensation costs could effectively rein in the growth in property tax bills, and eventually provide property tax relief.

Those changes would also empower local leaders to better bring property taxes into line with what homeowners can afford during economic downturns.

Illinoisans are desperate for property tax relief. Lawmakers should be desperate for reform.