Waste Watch: Nearly $100M of waste in Illinois state and local government

By Adam Schuster, Alec Mena, Travis Nix

Download Report

Illinois taxpayers are fed up and overtaxed. Residents have little faith that their governments are spending their tax dollars well – and for good reason.

The state’s most recent spending plan is out of balance by as much as $1.5 billion, and includes $54.2 million in wasteful spending and $27 million in pork-barrel spending. The line between pork and waste is admittedly blurry, but generally speaking, pork-barrel spending refers to special projects lawmakers sneak into the state budget that satisfy interests in their district. These projects may be appropriate to fund under different circumstances or by different means. Waste, on the other hand, refers to spending that does not serve a legitimate purpose of government. Given that lawmakers made the 1,245-page budget public just hours before voting on it, the amount of both waste and pork may come as a surprise to them as well as to their constituents.

Wasteful state spending includes:

- $13.1 million on an arts council chaired by the wife of Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan, which has been subject to criticism for misusing taxpayer funds

- $23.6 million on programs that encourage bike-riding in Illinois

- $3.6 million on the development of the World Shooting Recreational Complex in Sparta, in addition to $2.6 million on operating costs

- $75,000 to encourage young people to take up golf

- $25,000 on monarch butterflies

Pork project spending, which goes entirely to districts represented by state lawmakers who voted for the budget, includes:

- $10 million to rehabilitate the dilapidated and privately owned Uptown Theatre in Chicago

- $3.3 million to build a sports recreation facility in Chicago’s Morgan Park neighborhood

- $2.5 million to renovate greenhouses at Southern Illinois University

- $2 million for a racetrack in Madison County

- Nearly $1.4 million for improvements to Senka Park in Chicago

- $350,000 to Memorial Park District in Hillside to renovate a swimming pool

- $350,000 for a bike path, potentially in addition to other unspecified capital improvements, in the village of Romeoville

- $275,000 for a running track at Jesse Owens Park in Chicago

- $200,000 for renovations to a community swimming pool in the Chatham neighborhood of Chicago

- $100,000 for capital improvements in the Park District of Oak Park, including a new water playground

- $30,000 to build a water park in the city of Harvey

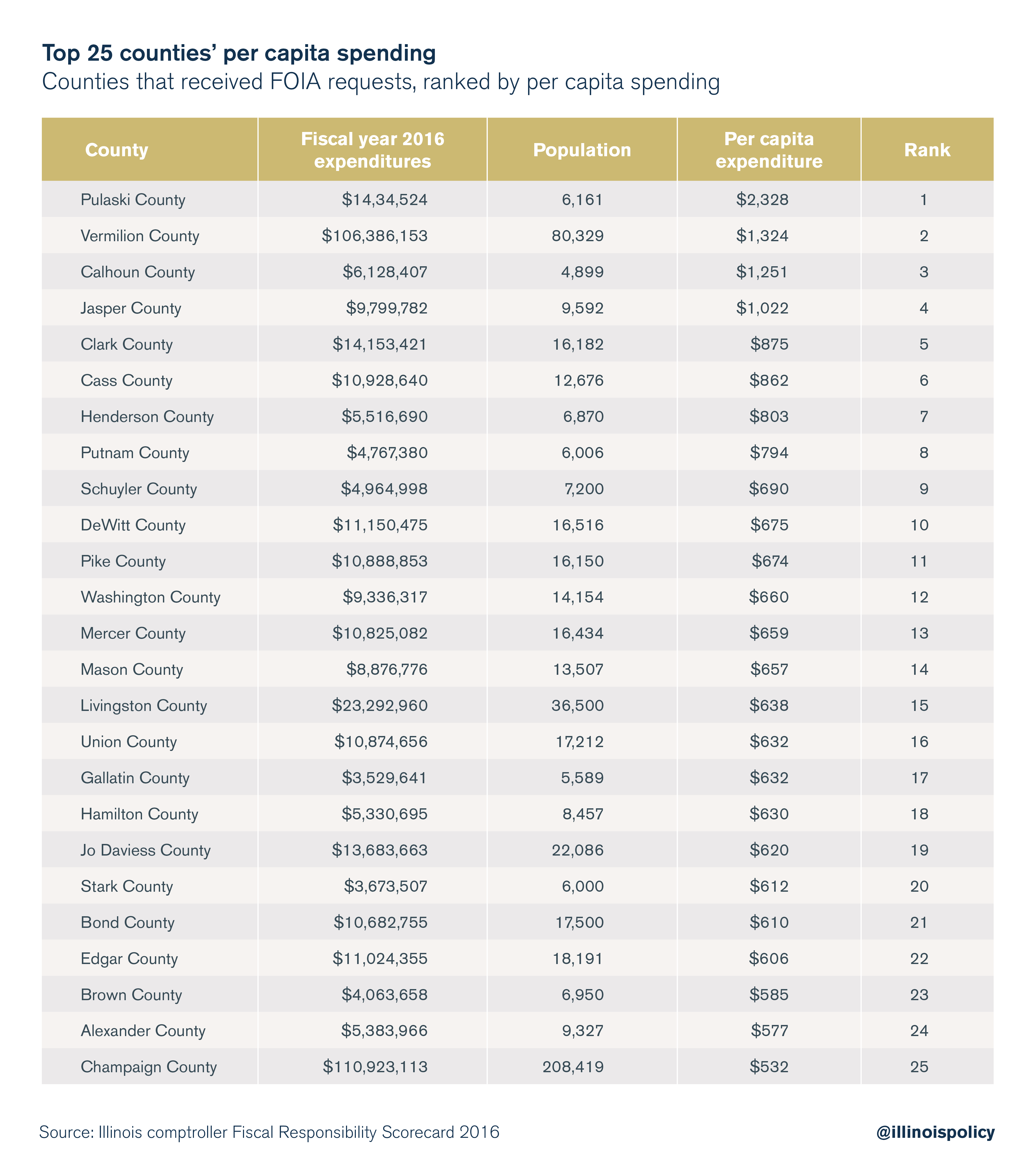

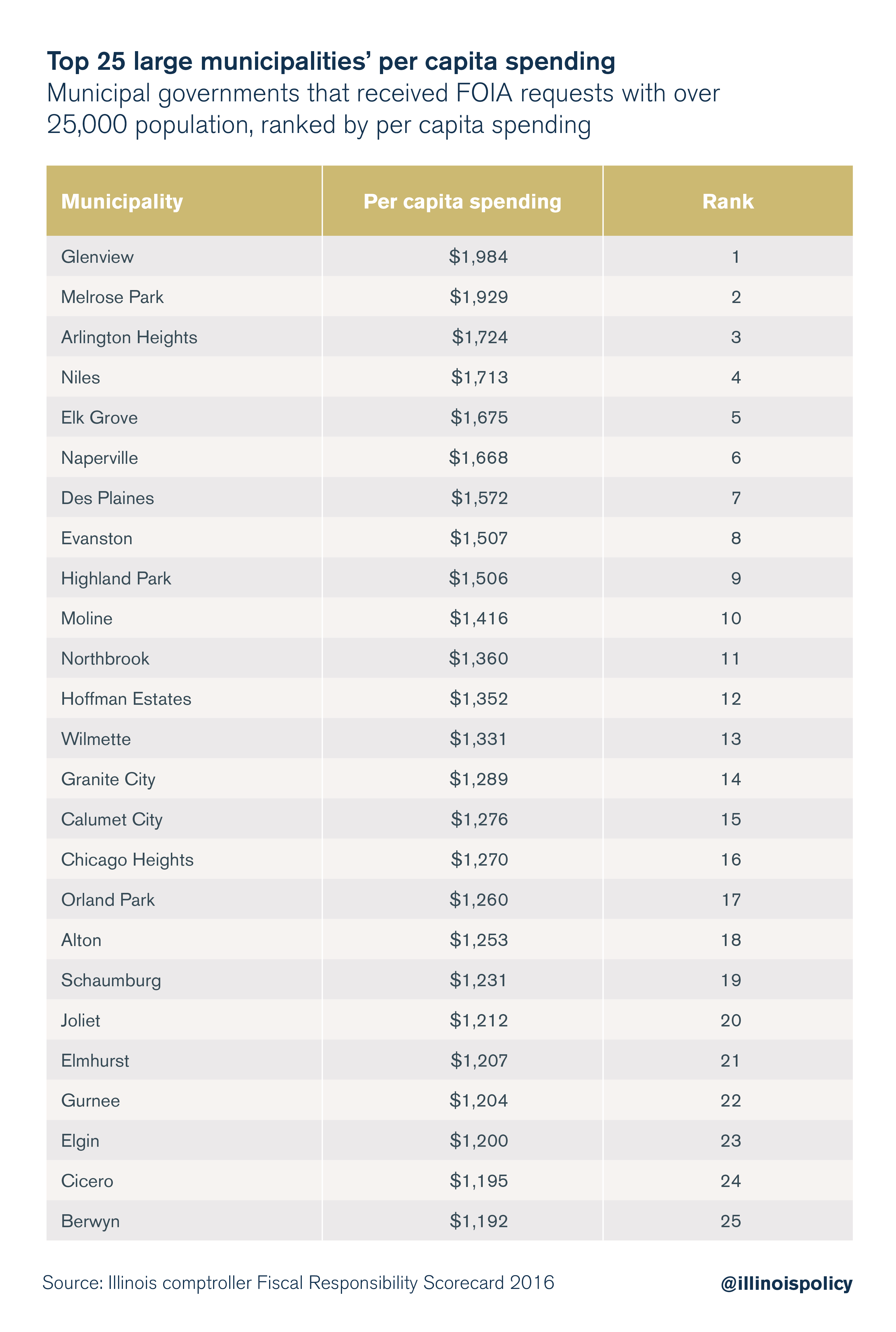

Illinoisans pay the second-highest property taxes in the nation. But the local governments levying those taxes waste a considerable amount of taxpayer money. Research for this report identified $15.9 million in wasteful spending from fiscal years 2015-2018 in just a small sample of the Prairie State’s approximately 7,000 units of local government, selected based on the top 25 per capita spenders. Highlights include:

- Municipalities spent a total of more than $2 million on lobbying.

- Park districts spent a total of more than $500,000 on lobbying.

- Park districts spent more than $1 million, while municipalities spent more than $2 million, on frivolous advertising and promotional materials, with much of that spending concentrated in only a few taxing bodies.

- Northbrook Park District spent over $3 million on “p cards,” or procurement cards, used for small purchases.

Taxpayer money also went to picnics, beer, candy, cookies, fast food, flowers, golf, custom t-shirts, newspaper and political blog subscriptions, and companies that make various handouts including pens, bags, beer koozies, bottle openers and drinkware. One local government spent thousands of dollars to drop marshmallows from a helicopter. In some cases, a significant amount of spending went to companies that had made large financial contributions to elected leaders’ political campaigns.

While the path to lower taxes and better credit ratings for Illinois governments primarily lies in structural reforms to the cost-drivers of government spending, wasteful spending – even when it doesn’t amount to billions of dollars – is a slap in the face to taxpayers. Public officials should pay taxpayers respect by eliminating spending that is obviously wasteful. If politicians were better stewards of taxpayer dollars, perhaps fewer Illinois residents would be heading for the exits.

Introduction

Wasteful government spending in Illinois has played a role in driving residents out of state and crippling government finances and bond ratings.

Illinois has one of the highest combined state and local tax burdens in the nation.1 Property taxes are the largest contributor to Illinoisans’ excessive tax burden. The state’s median effective property tax rate of 2.29 percent is the second-highest in the nation, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau.2

Evidence increasingly shows that Illinois’ high tax burden is a primary factor in its outmigration crisis. The state has seen four straight years of population decline, driven primarily by prime working-age adults fleeing to other states.3 A 2018 survey conducted by the Center for State Policy and Leadership at the University of Illinois Springfield and NPR Illinois found more than half of Illinois residents want to leave the state, and that taxes are the No. 1 reason.4

Experts have long argued that people are more willing to pay taxes when they see valuable government services in return, and when they generally trust their government officials.5 As such, property taxes have traditionally been justified as “user fees” and can increase home values when they are used to fund core government services, such as public safety and education.6

Unfortunately, Illinois taxpayers see too many of their tax dollars wasted, and polling has revealed that, compared with residents of the other 49 states, Illinoisans have the least confidence in their state government.7 This disconnect between taxes paid and valuable public services, along with low trust in government, helps explain why Illinois taxpayers are fleeing their high tax burdens.

Much of the misuse of tax dollars is related to structural problems in how Illinois governments spend money. For example, the largest increases in state spending have gone to health care coverage for government workers, often including lifetime retirement health care, and pension benefits. According to the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, growth in spending on government worker pensions and employee health insurance has far outpaced spending in every other area.8 From 2000 to 2018:

- Spending on pensions has grown 663 percent.

- Spending on employee health insurance has grown 215 percent.

- Spending on pre-K through 12th grade education has grown 65 percent.

All other spending has grown by just 16 percent.

At the local level, Illinois both has too much local government and spends too much on each layer of government, on average. With nearly 7,000 units of local government – the most in the nation – each local taxing body in Illinois serves an average of just over 1,800 people, the lowest among all states with populations above 10 million.9 This trend is also reflected in Illinois’ overabundance of school districts, with more than 850 districts serving an average of just over 2,300 students per district.10

When it comes to the cost of government, pensions are crowding out core services at the local level and causing property taxes to skyrocket. From 1996 to 2016, property taxes rose 52 percent in real terms, taking Illinois from around the national average in property tax collections to the second-highest in the nation. Over that same time period, more than half of every new property tax dollar went to pensions, benefits for government workers and debt service, not current government services.11 On education, Illinois spends nearly double the national average on employee benefits and general administration, and more than every neighboring state.12

While much of this overspending and mismanagement could easily be called wasteful, for the purposes of this report it will be considered “structural spending,” distinct from the waste detailed below.

In addition to unsustainable spending on pensions and benefits, Illinois governments also spend plenty of tax dollars on frivolous programs and purchases that can only be considered waste.

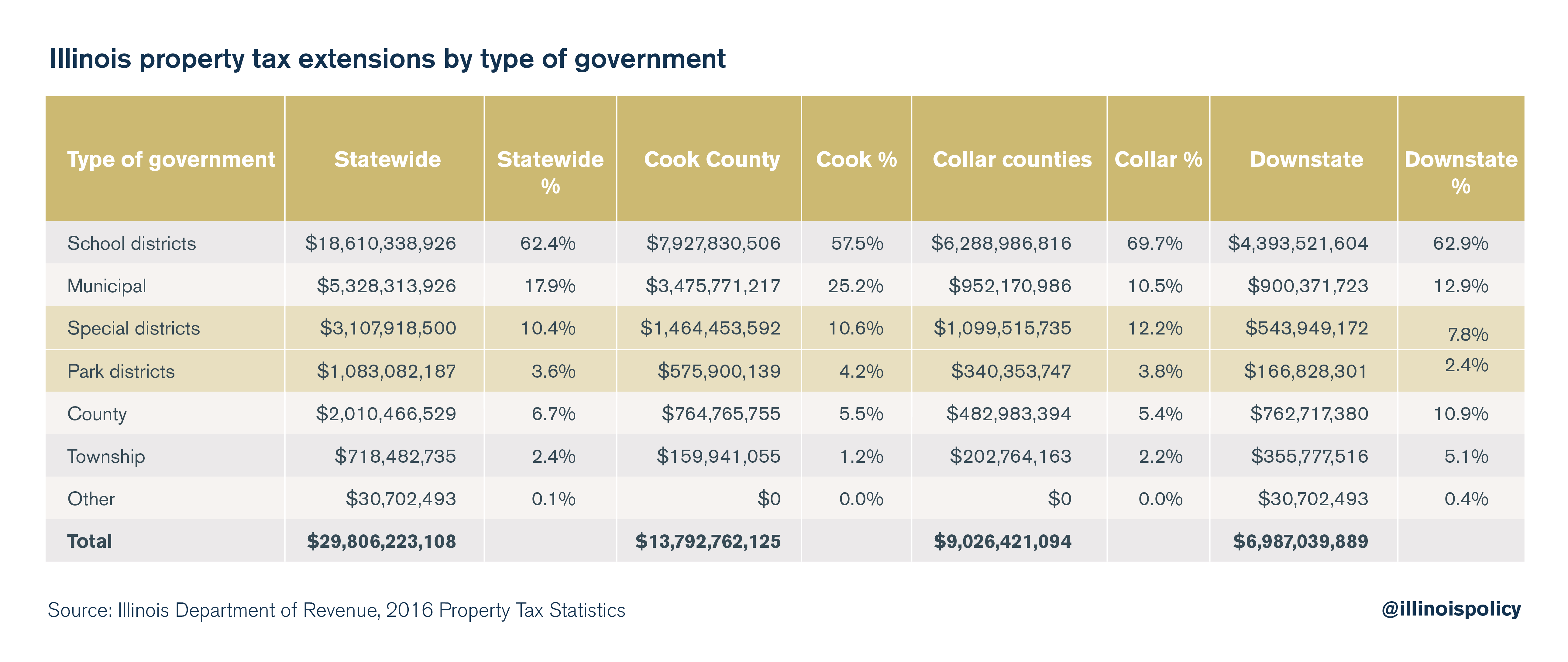

This report highlights nearly $97.2 million of waste in state and local government across Illinois, but excludes school districts. School district spending, which accounts for the largest portion of Illinoisans’ property tax bills, and is one of the largest single items in the state budget, will be addressed in a separate report. See Appendix A for a full ranking of property taxes by type of local government.

This $97.2 million of waste is only the tip of the iceberg. Examining the individual budgets of nearly 7,000 government bodies in Illinois is impossible due to poor financial transparency and a lack of records in many of these entities, not to mention the sheer volume of them.

This report focuses on egregious examples of waste by some of the biggest spenders in Illinois. Because property taxes are the largest driver of Illinoisans’ tax burden, and because the Illinois Policy Institute has focused on solutions to state-level financial problems in other reports, this report shines a spotlight on local governments more than on state agencies.

Local elections also suffer from chronically low turnout in Illinois.13 With fewer taxpayers paying attention and checking the excesses of local government, elected officials face less pressure to be transparent, and may find it easier to misuse taxpayer funds.

Ultimately, balancing budgets and lowering taxes require deep structural changes in the way Illinois governments spend money. More savings can be found reforming structural overspending than by eliminating waste. But at the very least, taxpayers should demand their elected officials immediately cut frivolous spending from their budgets. That’s money that can be spent on more important things, such as public safety and social services.

Cutting wasteful government spending is a moral imperative: Illinois taxpayers deserve careful stewardship of their tax dollars.

Methodology

Local government bodies were selected for initial inquiry based on the top 25 municipalities, counties and park districts for per capita spending, according to the Illinois comptroller’s office. For a full listing of these governments, see Appendix B. In the comptroller’s data, municipalities are divided into large and small municipalities, with the dividing line drawn at populations of over or under 25,000 residents. However, not all counties and small municipalities selected were able to provide sufficient data for a financial review.

Nearly all of the data presented in this report were received through Freedom of Information Act, or FOIA, requests. However, waste in the fiscal year 2019 state budget was found by analyzing this year’s appropriations bill,14 and online financial reporting was used to supplement deficiencies in FOIA responses from some municipalities.

Across local governments, certain categories were analyzed uniformly as common types of wasteful spending. This includes:

- Spending on advertising, promotional materials and handouts

- Spending on lobbying

- The difference between the taxing body’s highest paid employee and the median family income for that municipality or county

Promotional spending was compiled by performing a keyword search for common terms.15 If a keyword search turned up items that appeared to be legitimate uses of government funds – such as a search for “shirt” uncovering spending on employee uniforms – the line item was excluded.

Other waste was identified by meticulously combing through vendor disbursement lists to find questionable items. This method is necessarily incomplete because it relies on self-reported financial information from government officials. Because of that limitation, it is impossible to determine whether expense reports are accurate and free of fraud.

For example, former College of DuPage President Robert Breuder was found to have hidden about $95 million of spending from the university board and was dismissed in 2015. Such hidden spending included hundreds of thousands of dollars paid to businesses connected to college leadership, payments for satellite phones used for Breuder’s exotic hunting trips, membership to a private shooting club, and nearly $250,000 dollars for alcohol, misleadingly listed on ledger lines as “instructional supplies.”16 In another example, former Ford Heights Mayor Charles Griffin faced felony charges for allegedly diverting more than $147,000 in taxpayer funds into personal bank accounts.17

Perhaps the worst example of dishonest financial practices in recent memory was the case of Rita Crundwell, former comptroller of Dixon, Illinois. Crundwell was sentenced to 20 years in prison after stealing more than $53 million from taxpayers.18

If financial information is misreported, wasteful spending cannot be identified by relying on official resources.

Where possible, existing news reports of wasteful spending were used to supplement the original data collection.

Spending that might have appeared wasteful at first glance, but that could be tied to a legitimate function of government upon further inspection, was excluded.

For example, there are certain vendors whose services would be hard to imagine constituting a legitimate government purchase. But some expenditures are actually repayments for mistaken taxes and government fees. For example, in Schaumburg, a $25 payment from the city to GameWorks was not for video games for city employees, but a refund for a duplicate license. Similarly, a $500 payment from Schaumburg to Red Lobster was not for butter-dipped dinners, but for a water bill refund.

Some items governments should not spend taxpayer money on in general can be justified in certain contexts. Using Schaumburg again as an example, nearly $5,000 in brochure spending to Positive Promotions Inc. for disaster preparedness was excluded from the waste in the “promotions and advertising” category. Over $3,300 the village of Schaumburg spent on brochures relating to public safety services was also excluded.

For items that appeared out of the ordinary and for which insufficient information was provided in the original FOIA response to assess their wastefulness, municipalities were given a chance to explain or justify the spending. Most local governments, other than Rosemont, Evanston and Barrington Park District, failed to provide further comment or justification for the public purpose behind the spending identified by the time of publication. Where a sufficient justification for spending was provided, the spending was removed from the waste total. In other cases, the public comment from the municipality is provided for further context.

The timeline of the report is fiscal years 2015-2018 for local governments, selected to partially coincide with the state’s budget impasse. With state elected officials fighting over spending, local government budgets endured less scrutiny. Taxpayers deserve to know how their local tax dollars were spent during this time.

State budget: $54 million in waste, $27 million in pork

According to the state itself, Illinois’ most recent spending plan is yet another in an unfortunate string of unbalanced budgets. State lawmakers have not passed a truly balanced budget since at least 2001.19 Despite claims from some lawmakers that the fiscal year 2019 budget is balanced, the state of Illinois admitted to a $1.2 billion structural deficit in an August statement to potential investors.20

The Illinois Policy Institute projected the General Assembly’s spending plan was out of balance by as much as $1.5 billion shortly after the bill was made public.21

Most of this overspending is structural, such as costs for pensions and government workers’ health care, but the fiscal year 2019 budget also contains $81.3 million in waste and pork spending. For the purposes of this report, wasteful spending is money the state should not be spending at all, while pork spending is for projects that allow individual members to “bring home the bacon” to their district by securing state funding for localized projects.22 Pork spending is often included in legislation to encourage members to vote yes. Pork spending often lacks transparent legislative debate and encourages overspending, since projects are used for “vote buying” rather than appropriated through the normal grant-making process.

While some of the spending highlighted in this report could easily be classified as both waste and pork, the difference is that waste is spending on something that is obviously not a proper government function to begin with, while pork is for projects that may be appropriate uses of taxpayer dollars, but should not be coming from the state, or that at least appear to be examples of lawmakers slipping in special projects for their districts.

Commentators have already criticized the $224 million to be spent in connection with the Obama Presidential Center.23 This report details other examples of wasteful spending that have not received as extensive media coverage.

State waste: $54 million

The largest single item of wasteful spending in the latest state budget is $13.1 million for an organization chaired by Speaker of the Illinois House Mike Madigan’s wife, Shirley Madigan. The organization, the Illinois Arts Council Agency, or IACA, is tasked with encouraging development of the arts throughout the state. On its face, this is a questionable function for state government, especially a government with billions of dollars in debt and chronically unbalanced budgets. Shirley Madigan has chaired the organization since 1983 and has served on the council since 1976, nearly as long as Mike Madigan has been in the Illinois House, according to Adam Andrzejewski, the founder and CEO of openthebooks.com.24

To make matters worse, IACA has been the subject of a number of public controversies. In 2016, the Edgar County Watchdogs, represented by the Liberty Justice Center,25 filed a lawsuit against IACA for allegedly violating the Freedom of Information Act by both taking too long to respond to requests for information and by not providing the requested information.26

In 2017, Andrzejewski called for Shirley Madigan to be replaced as chair. According to Andrzejewski, IACA had “conferred grants without official meetings, ignored rampant conflicts of interest, and funneled millions of taxpayer dollars to asset-rich organizations … which don’t need public money.”27 Many of IACA’s grantees don’t appear to be traditional arts groups at all, but rather well-to-do media nonprofits from whom IACA might have been seeking favorable press.28

Not all wasteful spending has such clear political connections, however. The state is spending over $23.6 million on bicycle-related programs, for example. The largest portion of this – $13.3 million – is appropriated for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, or IDNR, to assist local governments in the acquisition and development of bike paths. A separate grant of $7.8 million to IDNR appears to be for the same purpose, developing and maintaining bike paths, but with no mention of local governments. More bike path spending for particular projects is detailed in the pork section, but those grants typically come from the Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity’s Build Illinois Fund. In other words, the state budget includes two large bike path grants to be handed out through IDNR, in addition to a few specific legislative grants for bike paths. With billions of dollars in unpaid bills at the state level, $21 million from IDNR is money the state cannot afford to be spending on unidentified local projects, even if bike paths would be a nice investment for a fiscally healthy government.

In addition to the money to acquire and develop bike paths, the state is spending nearly $2.5 million on its bikeways program, which exists to perform research, education, lobbying and more to coordinate bikeways across the state,29 and an additional $45,000 on education programs to instruct bikers and motorists on how to share the road.

While safe biking is a laudable goal, these programs may not be effective at changing culture, and are certainly not affordable for a state billions of dollars in debt.

Less justifiable than promoting bicycle safety is nearly $4 million the state spends on various county fairs. Some of this money is for rehabilitation and operation of fair facilities, but nearly half is for the vague goal of promoting and encouraging the fairs.

Other wasteful spending includes:

- $3.6 million on the development of the World Shooting Recreational Complex in Sparta, and another $2.6 million on operating costs.

- $100,000 to build a National Railroad Hall of Fame in Galesburg, Illinois.

- $75,000 to the Illinois Professional Golfers Association Foundation to help association members expose Illinois youths to the game of golf.

- Nearly $63,000 for the Daily Egyptian newspaper, the student newspaper at Southern Illinois University. This is the only student newspaper being funded directly by the state.

- $25,000 in general grants to the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts of America, along with two individual $50,000 grants to particular scout organizations: one to the Blackhawk Area Council of Boy Scouts of America and another to the Girl Scouts Rock River Valley Council. While scouts may be valuable organizations, they should not be taxpayer-funded.

- $25,000 for expenses related to the development, enhancement and restoration of the monarch butterfly habitat, a pet project of state Sen. Melinda Bush, D-Grayslake.30

- $20,000 to Ducks Unlimited Inc. for wetland conservation projects and public relations.

Total wasteful state spending is rounded out by the inclusion of $4.1 million “for the purpose of attracting waterfowl” and improving migratory waterfowl areas in the state, and $2.7 million “for the preservation and maintenance of a high quality fish and wildlife habitat and to promote the heritage of outdoor sports in Illinois.”

Some of these appropriations are from funds that receive money from sources such as the sale of specialty license plates and stamps. However, at a time when Illinois is sweeping money from other dedicated funds, such as the Mental Health Fund, to narrow deficits, preserving these special spending carve-outs is a questionable budgeting practice.

While eliminating all of this spending still wouldn’t balance the budget, lawmakers should pluck this low-hanging fruit as a small step toward improving the state’s finances.

Pork spending: $27 million

One of the key sources of pork-barrel spending is the Build Illinois Bond Fund operated by the Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity, or DCEO. The most effective lawmakers at “bringing home the bacon” are Democrats from Chicago. Nearly $17.3 million of the total pork spending identified is for districts represented by Chicago-area lawmakers.

The largest pork project in the budget is a $10 million grant to the Uptown Theatre in Chicago for capital improvements. According to the Chicago Tribune, the grant is part of a planned $75 million restoration project backed by Mayor Rahm Emanuel. Efforts to rehabilitate the massive theater have persisted for decades, but private developers found the profits uncertain and the price tag high, and no politician had succeeded in putting taxpayers on the hook until now.31

The theater will also receive $30 million in Chicago taxpayer money – including $13 million in tax increment financing – even though the long-vacant building is privately owned by Jam Productions, a company that acquired the theater through a judicial sale in 2008.32

Although some may value the Uptown Theatre as a landmark, it has not seen a live concert since 1981.33 If a private company believes the theater can turn a profit, it should be up to that company to invest in the property. Taxpayers should not be forced to pick up a big piece of the restoration tab.

Other multimillion-dollar pork projects include:

- $3.3 million to build a sports recreation facility in the Chicago neighborhood of Morgan Park. Local state Rep. Justin Slaughter, D-Chicago, and local state Sen. Emil Jones III, D-Chicago, both voted for the budget.

- $2.5 million for the renovation of greenhouses at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. Local state Rep. Terri Bryant, R-Murphysboro, and local state Sen. Paul Schimpf, R-Waterloo, both voted for the budget.

- $2 million for a racetrack in Madison County. Local state Rep. Jay Hoffman, D-Swansea, and local state Sen. James Clayborne, D-Belleville, both voted for the budget. This comes on top of a separate $25,000 grant to the Madison County Fair Association mentioned in the waste section. Local state Rep. Charles Meier, R-Okawville, voted for the budget.

- More than $1.3 million for improvements in Senka Park in Chicago. Local state Sen. Martin Sandoval, D-Chicago, voted for the budget.

While no single item breaks the million-dollar mark on its own, the budget includes at least another 48 pork projects that total $7.9 million in spending. Some of these projects include:

- $350,000 for the Memorial Park District in Hillside to renovate a swimming pool. Both local state Rep. Emanuel Chris Welch, D-Hillside, and local state Sen. Kimberly Lightford, D-Maywood, voted for the budget.

- $350,000 for a bike path in the village of Romeoville, potentially in addition to other unspecified capital improvements. This comes on top of the $21.1 million in waste the state spends on bike paths. The village also received $337,500 for general infrastructure improvements. Local state Rep. John Connor, D-Lockport, and local state Sen. Pat McGuire, D-Crest Hill, both voted in favor of the budget.

- $275,000 for a running track at Jesse Owens Park in Chicago. Local state Rep. Marcus Evans, D-Chicago, and local state Sen. Elgie Sims, D-Chicago, both voted for the budget.

Evans and Sims also pulled in nearly $200,000 for renovations to a community swimming pool in the Chatham neighborhood of Chicago. - $100,000 for capital improvements in the Park District of Oak Park, including a new water playground at Rehm Pool. Local state Rep. La Shawn Ford, D-Chicago, and local state Sen. Kimberly Lightford, D-Maywood, both voted for the budget.

- $30,000 to Harvey Park District for a water park. Local state Rep. William Davis, D-Homewood, and state Sen. Napoleon Harris III, D-Harvey, both voted for the budget.

While this patchwork of projects may be useful to some Illinois residents, taxpayers can’t afford these state expenditures. What’s worse, many residents and lawmakers are likely unaware that these projects made their way into the budget at all, given the lack of transparency in this year’s budgeting process.

Local government: $16 million (fiscal years 2015-2018)

Property taxes, which are the main funding source for local governments, are one of the most painful taxes in Illinois. And yet, local governments use taxpayer money in all sorts of questionable ways. Much of this spending occurs in municipalities and park districts on promotional handouts, advertising, lobbying other units of government for more taxpayer funds, and much more. Some of the most egregious examples of waste are explained here in detail, but not all local waste found is identified by line item.

Municipalities: towns and cities

Intergovernmental and lobbying expenditures

Taxpayers expect services from their towns and cities, especially when they’re paying among the highest property taxes in the nation.

However, they may not appreciate their local governments spending taxpayer money to lobby other governments, or the significant amounts spent on advertising and promotional handouts, such as brochures, t-shirts, pens, drinkware and beer koozies.

Of the local governments that responded with usable data to the Institute’s FOIA request, 30 spent money on intergovernmental affairs and lobbying. This totaled over $2 million, mostly in dues or fees for membership in the lobbying organizations.

The largest portion comes from Arlington Heights, which spent almost $570,000 on the West Central Municipal Conference, or WCMC, in 2016 alone. WCMC was one of the top five recipients of taxpayer dollars among lobbying and government affairs groups in the sample. Each of these groups has a website detailing basic information, but often very little information about the causes they lobby for and against.

Not all of the legislation lobbied for by government bodies is bad, but it is nearly always self-interested. A prime example of self-interested governmental lobbying can be seen in opposition to House Bill 3133, filed in the General Assembly in spring 2018. This bill would have taken a positive step toward enabling property tax relief by making it easier to consolidate townships through citizen referendum.34 Some 341 individuals or organizations filed witness slips in opposition to the bill. Of those opponents, at least 220 were representing various Illinois township governments themselves. This is an example of government lobbying for its own existence – against the interest of taxpayers.

Spending on promotions, events and other nonessential items

Since many of the groups mentioned above often lobby for more money for towns and cities, it’s worth looking at how some of these same municipalities spend their money. While the municipalities that provided information to the Institute collectively spent more than $2 million on promotions and lobbying, the bulk of that spending is concentrated in the top 20.

Schaumburg

Local governments’ promotional spending is often simply irrational. The biggest spender, Schaumburg, spent $4,700 on a brochure called “Bike to Metra,” which simply tells residents how they can ride their bikes to the local Metra station, a task any GPS-enabled smartphone can accomplish for free. Schaumburg is a modern city with over 74,000 residents – it should not engage in this type of expensive hand-holding.

Schaumburg also spent a lot of money on tourism, amounting to nearly $1.6 million in total. Some of this money is listed as advertising above, but not all of it could clearly be identified as such. Almost $675,000 went to Meet Chicago Northwest, a convention and visitors bureau. Meet Chicago Northwest justifies this promotional spending by claiming it will increase overnight hotel stays, enhancing the local economy by bringing in more visitors.35 This is on top of about $920,000 recorded as going to the Greater Woodfield Convention & Visitors Bureau, which appears to be a prior name for the same entity, according to the “about” page of the bureau’s website.

Schaumburg’s hotel and convention center was expected to lose $6.8 million in net assets in 2016, as of the city’s most recent budget.36

Another area of big spending includes over $43,000 on brochures, primarily promoting the Prairie Center of the Arts, or PCA, a theater and entertainment center owned and operated by the city government. Schaumburg also spent over $1,400 advertising PCA with Tribune Media.

Other Schaumburg promotional spending includes:

- $21,400 for t-shirts at companies including Ad Images Inc., Creative Promotional Apparel Inc., and more.

- Nearly $14,000 for various items at companies that make knickknacks, including pens, bags, beer koozies, bottle openers and drinkware.

- $4,700 in online marketing, including nearly $1,200 to Facebook.

Outside of the promotional category, Schaumburg also wasted over $15,000 on candy and cookies in a series of payments to sweetservices.com and smileycookie.com, and $13,000 on food items at Panera Bread and Portillo’s Home Kitchen. The largest bill at Panera was almost $540, while the largest bill at Portillo’s was nearly $1,400.

Schaumburg also spent nearly $25,000 on flowers from vendors such as 1-800flowers.com and Bailey’s Flowers, and $4,400 for a subscription to the Chicago Sun-Times.

Bedford Park

Surprisingly, the next biggest spender in this category is the village of Bedford Park, which has a population of just about 580 people, but ranks third among small municipalities for per capita spending, at over $43,000 per resident. This small village spent $7,775 on t-shirts alone.

Bedford Park’s overspending goes beyond just advertising and promotional materials.

Perhaps the most ridiculous spending in Bedford Park is on annual picnics, which cost an average of $45,700 per year, totaling more than $140,000 over the course of three years. The village spent over $4,000 on beer alone for these picnics. Residents are also paying big money for golf outings, which cost nearly $34,000 in 2015 and nearly $40,000 in 2017. The 2016 golf outing’s $10,000 cost was more modest, but wasteful nonetheless.

Food for these outings can be expensive, with Bedford Park spending over $1,300 on hot dogs for one event in 2015. Bedford also spent $330 at Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen, the fast-food chicken restaurant, in summer of 2017, and over $150,000 on luncheons over the time period examined.

Bedford Park also paid $2,000 over four years to Ahead of Our Time Publishing in subscription fees to the Springfield-based political blog Capitol Fax.

But Schaumburg and Bedford Park are far from the only municipalities wasting taxpayer money.

Berwyn

The city of Berwyn, classified as a large municipality with a population of over 55,000, spent more than $10,000 on t-shirt design and printing at Art Flo Screen Printing & Embroidery. The city also paid nearly $4,000 in subscription fees to the New York Times.

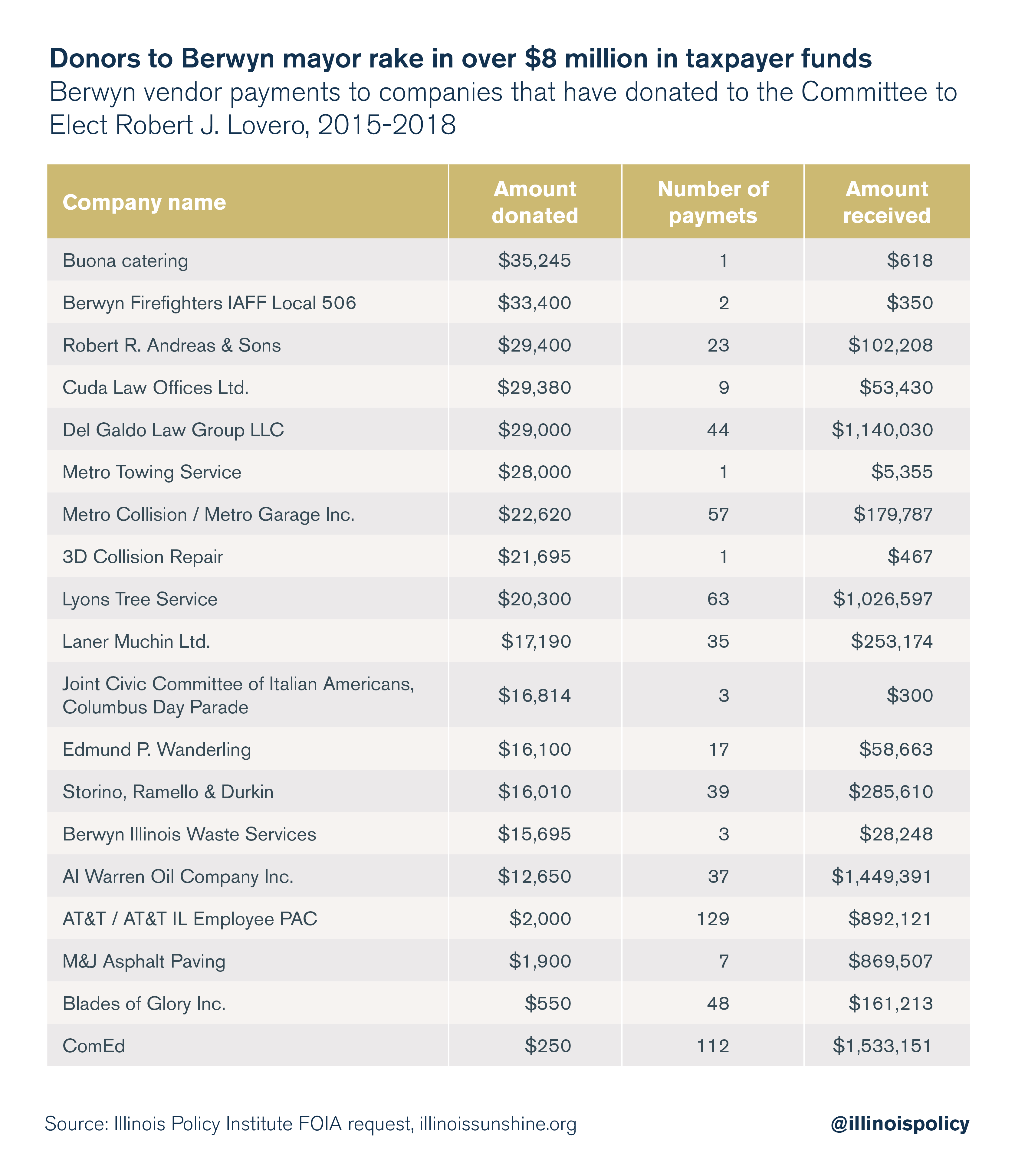

Over the past three and a half years, 14 companies that are top donors to Berwyn’s mayor’s election have collectively received over $8 million in payments from city taxpayers.

Rosemont

Rosemont is a small village with a population of just over 4,000, but has many business interests. The village spends big on:

- The Chicago Wolves hockey team, for a price tag of nearly $3 million

- Over $250,000 in catering costs for Rosemont Catering

- Nearly $240,000 on video development to Big Shoulders Digital Video Productions

- $225,000 at iFly Indoor Skydiving

- Over $200,000 to Verizon Wireless for cellphone service

- Nearly $200,000 to Disturbing Productions LLC to operate a haunted house

The village of Rosemont also spent $65,000 on Gino’s East pizza and more than $8,500 at McDonald’s.

Rosemont’s vendor files do not include descriptions of payments, so the exact purpose of this spending is unclear from financial records alone. According to Rosemont’s response to the Institute’s request for comment, the payments to the Chicago Wolves and Disturbing Productions are part of revenue sharing agreements. The $250,000 that went to the catering company included $66,785 on equipment to remodel a ballroom as well as $32,486 on a banquet for the DePaul University men’s basketball team at Allstate Arena. The village also disclosed that 84 employees receive taxpayer-funded cellphone service, which includes one Rosemont Chamber of Commerce employee and eight at Rosemont Health and Fitness, in addition to the city’s traditional government employees.

Rosemont also spent $60 million in tax increment financing on a new baseball stadium.37

Unfortunately, this type of spending is not rare for Illinois governments. Thanks to former Gov. Jim Edgar’s insistence on keeping the Chicago White Sox in Illinois, taxpayers spent $36 million on U.S Cellular Field in 2016,38 now Guaranteed Rate Field.

Evanston

Sometimes, taxpayer money is handed out in cash, making it hard to track. The city of Evanston recorded handing out petty cash on 33 different occasions in 2018 alone, totaling more than $4,000. That excludes a $7,500 petty cash allotment for a gun buyback program that was funded by an anonymous donor, although news reports state that only $3,200 was spent on the event.39

In addition to spending thousands trying to get firearms off the streets, the city also spent almost $20,000 on fencing instruction and $4,400 on karate instruction. Other instructional classes include $1,800 for magic lessons, $1,000 on posture training known as the “Alexander Technique” and $240 on fitness training. The city asserted via email that four of these five instructional classes are profitable, with karate instruction being the outlier. Still, these are services that could be run privately, with space leased by the city. It is questionable whether these services are an appropriate function of government and whether taxpayer-financed expenditures are the most efficient way to provide these services.

Among Evanston’s promotional spending was $100,000 to produce Evanston Life magazine and seasonal summer and spring magazines. Evanston even spent close to $640 of taxpayer money on a Snapchat filter.

Evanston’s over $30,000 in spending on t-shirts includes $2,130.99 on shirts for the “Zombie Scramble,” a zombie-themed recreational event, which the city says is factored into the cost of admission and therefore financed by user fees.

Evanston also spent at least $2,200 to have marshmallows dropped from a helicopter during a children’s event. The city’s inaugural Marshmallow Drop was heralded as “a blizzard of thousands of marshmallows” dropped from the sky.40 In this event, marshmallows are dropped into a field where children wait behind ropes. Once given the signal, the kids run out to collect as many as they can, which they can trade in for other treats. Signs caution the children not to eat the marshmallows.

The largest portions of spending on this event identified in the city’s financial records were $1,000 to pay for the helicopter itself, and close to $740 for backpacks.

According to reporting in Evanston Now, however, the event may have cost even more – as much as $4,420.41 The event was not funded by user fees, since the city did not charge admission.42

The Evanston RoundTable reported that the event did not go exactly as planned, as several loads of marshmallows were never even dropped from the helicopter.43

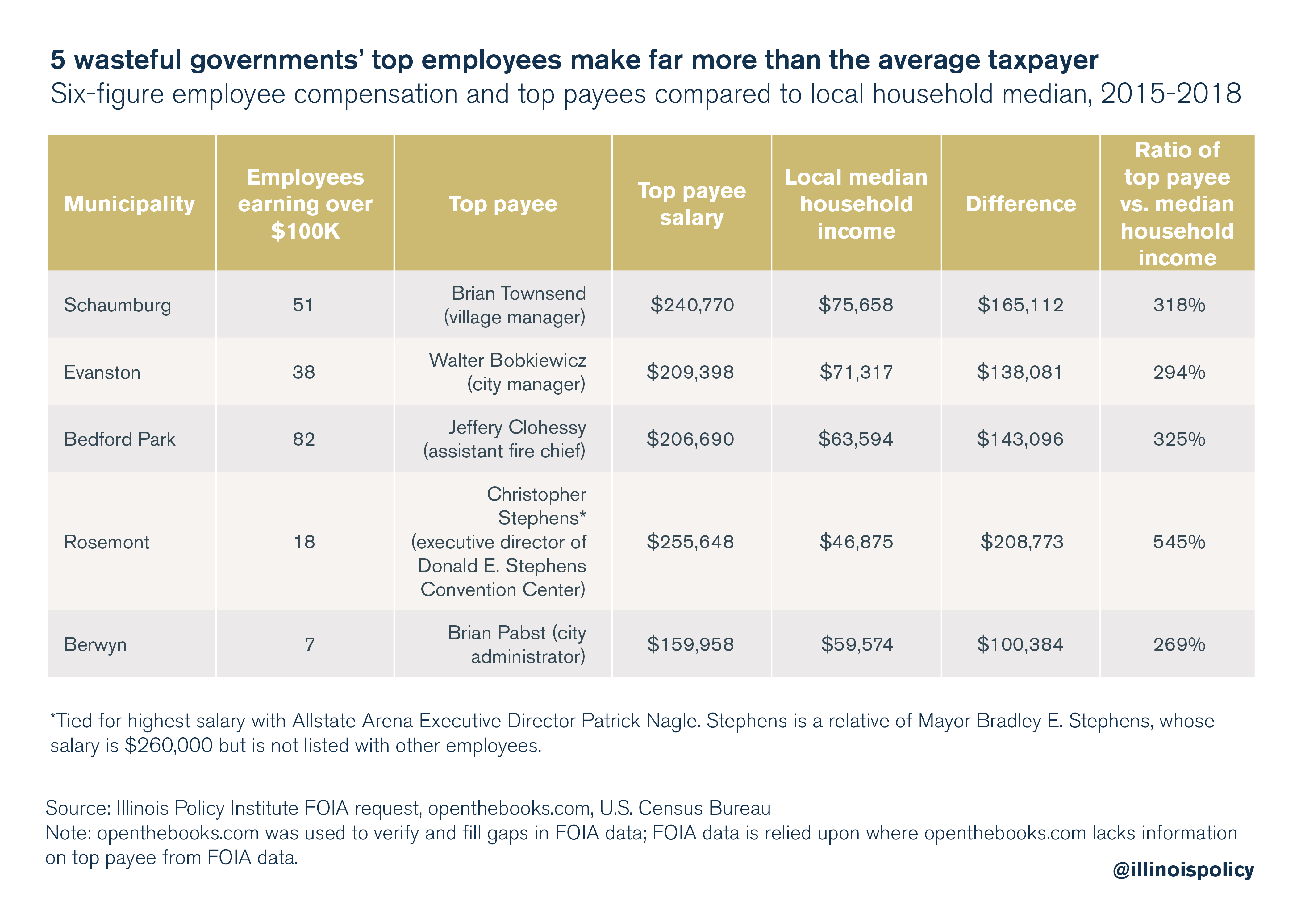

Employee pay

Not only do these cities spend excessively on advertising and lobbying, but they also pay many of their employees much more than the average local taxpayer earns.

On top of their base salaries, many of these employees also earn generous benefits and time off.

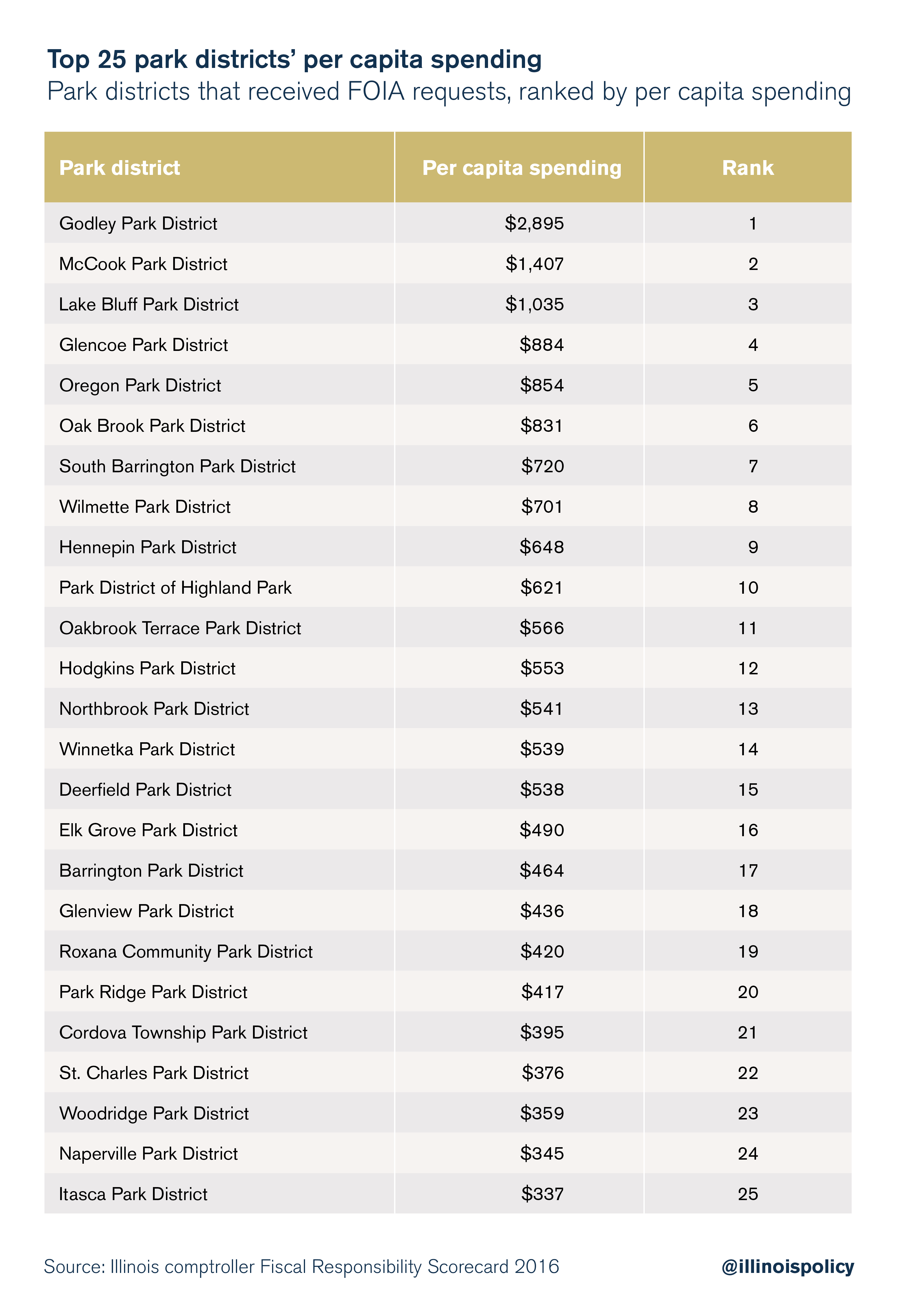

Park districts

Collectively, special districts account for over 10 percent of statewide property tax extensions. Park districts are the largest form of special districts, accounting for nearly 4 percent of all property tax collections.

Much like municipalities, park districts are also full of wasteful spending.

Lobbying and intergovernmental affairs

Park district spending on intergovernmental affairs and lobbying primarily goes to three groups: the Illinois Association of Park Districts, or IAPD; the National Recreation and Park Association, or NRPA; and the Illinois Park & Recreation Association, or IPRA. These groups, which are funded by taxpayers, lobby elected legislators on a range of issues, from public smoking bans to increased funding for after-school programs hosted by park districts.

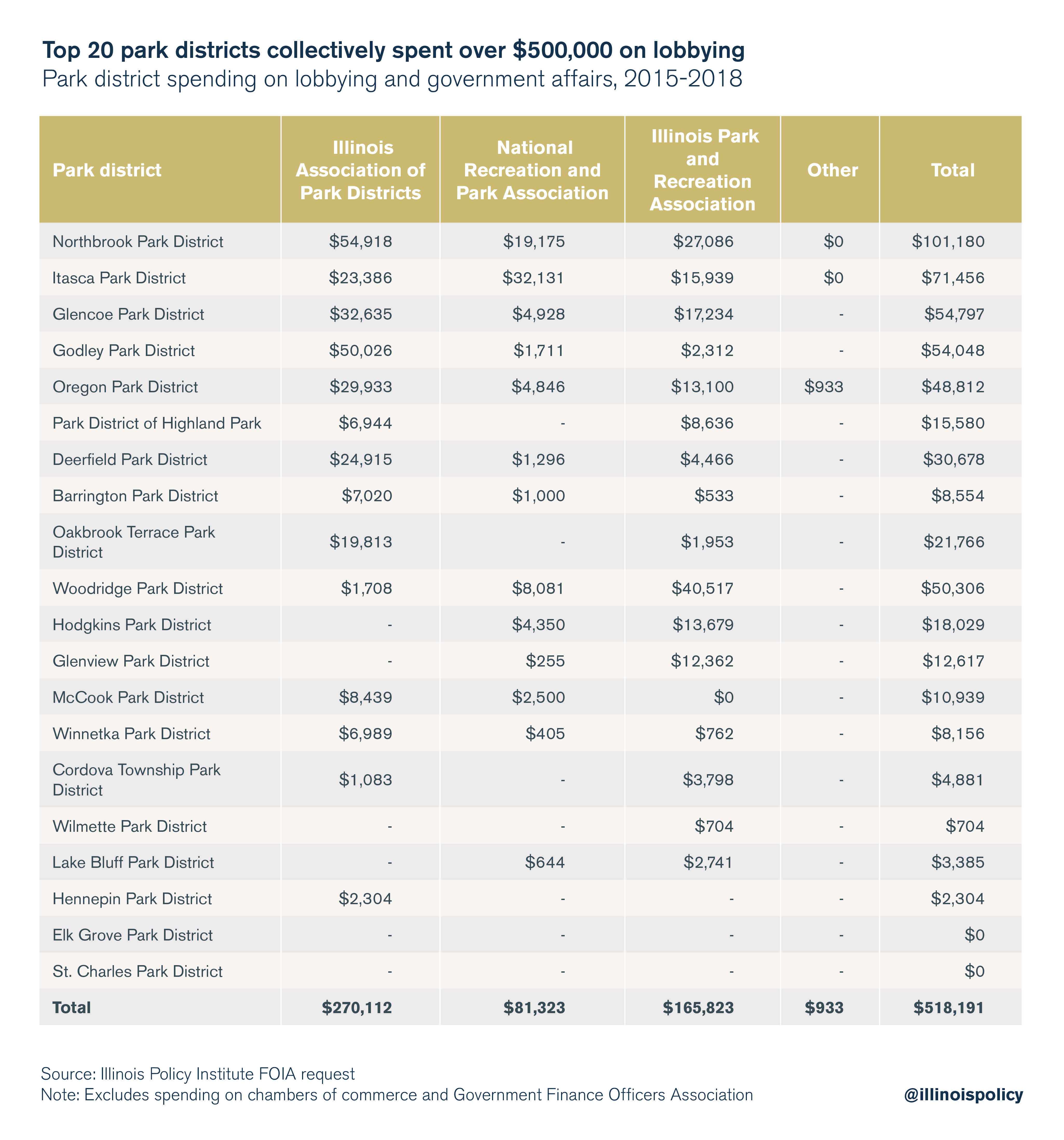

In terms of per capita spending, the top 20 park districts collectively spent over $500,000 on lobbying and intergovernmental affairs from 2015 to 2018.

Northbrook Park District is No. 1 in this category, accounting for nearly 20 percent of total spending. Much of the spending across this category pays for intergovernmental conferences, which can be a big expense for taxpayers.

Northbrook Park District spent over $16,000 on registration, housing and transportation expenses to attend NRPA conferences, including thousands of dollars to attend a conference in New Orleans in spring 2017. This conference included “exhibit hall offerings … including landscape architecture, aquatics, fitness, city planning, … and more” – subjects for which training could be done locally at far less expense than traveling to an out-of-state conference. According to the group’s blog, “sometimes, it’s easy to get lost in the exhibit hall with such amazing displays to distract you.”44

Barrington Park District employees also attended the spring 2017 NRPA conference, spending $1,723 in temporary-housing costs on top of $1,900 in per diem petty cash for five employees accepting awards. In fall of that year, a second conference cost Barrington taxpayers $2,765 for another trip to New Orleans, plus $450 in petty cash for one attendee and $328 in airfare.

Barrington Park District also spent money on conferences closer to home. An IAPD conference in 2017 cost $5,000 for dinner, transportation and per diem expenses for 13 people. The district also attended a joint IAPD/IPRA conference in 2016, spending $1,975 on lodging at the Hyatt Regency Chicago.

The Hyatt Regency seems to be a favorite for park employees. The Oakbrook Terrace Park District spent $2,427 on an IPRA conference held at the franchise in 2015. Merely registering to attend this conference cost Hodgkins Park District $250 per person.

Promotional spending

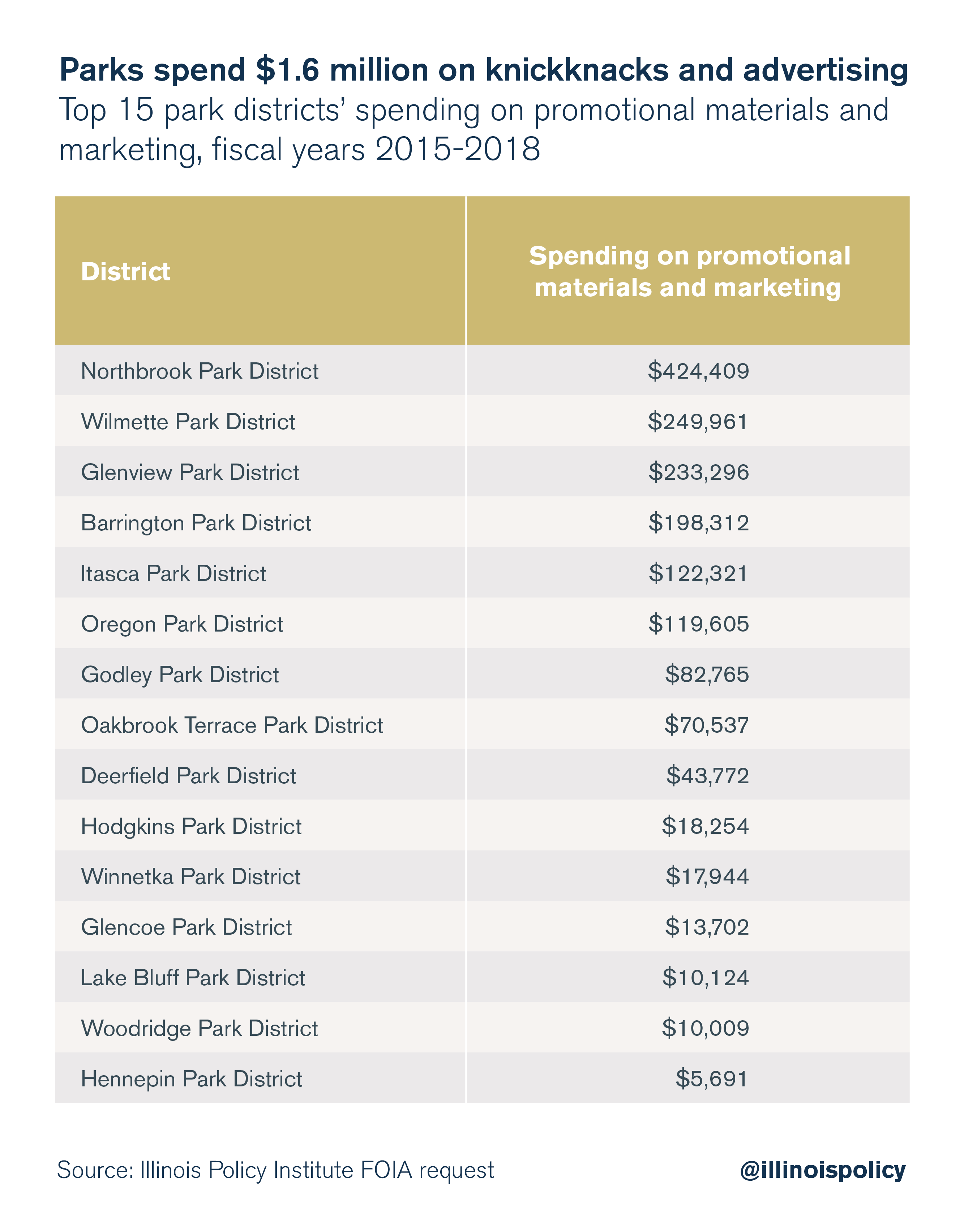

IAPD also hosts an annual “Parks Day” at the Illinois State Capitol, giving park districts an additional opportunity to waste money on promotional spending and handouts.

Collectively, the top 15 park districts cost taxpayers $1.6 million in promotional spending.

The top spender in this category, again, was Northbrook Park District, accounting for 26 percent of all promotional and advertising spending. The district spent almost $200,000 on brochures and guides, and almost $50,000 on promotional t-shirts over the three-year period. The district also spent over $40,000 on paid advertising, including $666 on Facebook ads and $140 for district employees to attend a class on social media marketing.

While Northbrook is the worst offender, many other park districts overspent on promotional materials and advertising.

- Barrington Park District spent $66,634 on seasonal brochures over the three-year time period, and $598 on a fitness center postcard mailer in 2015.

- Itasca Park District poured $88,939 into making and mailing its 2015-2018 seasonal brochures, $421 on postcards, and another $5,421 purchasing branded materials including pens, candy, umbrellas, rulers, spoons, towels and ponchos. The district also spent $27,540 on online and print advertising.

- Oakbrook Terrace Park District spent $64,368 on its seasonal brochures during this period, for an average annual cost of $26,092 per year. The district also spent over $6,000 on advertising, including online marketing.

- The Park District of Highland Park spent $82,092 on media marketing.

- Wilmette Park District spent $72,681 producing its brochures, and another $177,279 on its camp and leisure guides.

- Deerfield Park District spent over $40,000 on media marketing.

- Godley Park District spent $33,725 producing its annual brochures in fiscal year 2017 alone, and another $24,039 in fiscal year 2018. That’s on top of the $45,910 the district spent on marketing over this time period.

- Hodgkins Park District spent $18,164 on seasonal brochures and $650 on wristbands.

- Winnetka Park District spent $17,944 on media and marketing companies.

- Glencoe Park District spent over $13,000 on paid advertisements.

- Lake Bluff Park District has spent $8,894 producing promotional postcards since 2016, and more than $1,000 on paid advertising.

- Of the $26,600 Oregon Park District spent on advertising and promotional materials between 2014 and 2017, $2,543 went to Facebook ads.

- Elk Grove Park District made a $4,600 payment to a local golf magazine.

- Woodridge Park District spent over $1,700 on wristbands, on top of over $15,000 on advertising and marketing.

Northbrook Park District spent over $3 million on “p cards,” or procurement cards, through 14,243 small transactions. The use of procurement cards by Lake County has been criticized by CBS Chicago for its lack of transparency and its potential to allow frivolous spending, much like petty cash.45 In Northbrook, uses of purchasing cards included spending on Amazon Marketplace, Jewel Osco, the Fireside Dinner Theatre, Target, Walgreens, Michaels, Chipotle Mexican Grill, Jake’s Pizza and many other small purchases.

Most people love parks, but wasteful expenditures such as these may lead taxpayers to reconsider the value of their tax dollars flowing to their park districts.

Cicero and county government: Dishonorable mentions and taxpayer transparency laws

While wasting taxpayer dollars is a serious problem, hiding public spending from taxpayers is even worse. The local governments highlighted in this report are not always good stewards of taxpayer funds, but they deserve credit for at least making sufficient financial information available to allow for an examination of their spending. Far too many municipalities and counties do not provide financial information online, and several governments that received Freedom of Information Act, or FOIA, requests from the Institute either could not reply because they did not keep sufficient records or replied with data that were disorganized and impossible to decipher. This problem is especially pronounced among smaller municipalities and rural counties with small populations.

Of the 25 counties selected, only nine were able to provide any information at all. As a result, county government does not have its own section in this report.

Of the towns examined, Cicero is the worst offender in lacking transparency. Every government body in the top 25 for per capita spending received the same request for information, but only Cicero denied the request. The original FOIA request asked for the following documents between fiscal years 2015 and 2018:

- Annual budgets

- Any treasurer’s or financial audit reports

- Employee compensation disclosure records

- Vendor disbursement or invoice records

Cicero responded with a rejection letter June 18, explaining that to fulfill the request would be unduly burdensome, a condition under which public bodies are exempt from FOIA requests. However, Cicero’s denial letter stated “if your request can be narrowed … resubmit your FOIA request and the Town will respond accordingly.” The Illinois Policy Institute responded by narrowing the request, clarifying that individual vendor invoices were not necessary and that a summary of disbursements or a check register was sufficient. Cicero did not respond to the second, narrowed request, an apparent violation of FOIA.

Many other municipalities provided lists of payments made to vendors, but included no detail as to what the payments were for. Some municipalities provided data that were so disorganized as to be nearly unreadable.

Much of the poor financial record keeping by local governments can be remedied with stricter state transparency laws. While local officials should provide good information to taxpayers voluntarily, good government practices appear to be a wish more than a reality.

In 2017, House Bill 5522, a bill that would have improved transparency, passed in the Illinois House of Representatives 90-13, but died in the Senate.46 The bill would have required all local governments with budgets of over $1 million to maintain a website and post certain financial information, including:

- Annual budgets

- Financial reports and audits

- Information about employee compensation

- Contracts with lobbying firms

- Bids and contracts worth $25,000 or more

HB 5522 would have brought about much-needed reforms, and it should be taken up again by state lawmakers. The Illinois Policy Institute previously graded local governments on a 10-point transparency checklist and found 253 of the 339 government entities examined had failed.47

On top of deficiencies in the state’s transparency rules, the existing rules are not always followed. Public Act 97-0609 requires all municipalities participating in the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund to post on their website a list of all employees whose total compensation exceeds $75,000 within six days of passing a budget.48 However, no such list could be found for the town of Cicero.

Given Cicero’s history of misconduct allegations, it comes as no surprise that local officials do not want taxpayers to have the ability to scrutinize their spending habits.

The Better Government Association, or BGA, reported in 2016 that a former Clyde Park District employee, who had alleged the district fired her for speaking to the FBI about abuses of taxpayer funds, received $166,000 in a lawsuit settlement. Cicero Town President Larry Dominick, whose political allies oversee the park district, and his son Brian Dominick, who was sitting on the board at the time, were both originally named defendants in the case. The fired employee, Laura Perez-Garcia, alleged that Anthony Martinucci – a political colleague with Larry Dominick who holds three government jobs that collectively pull in a six-figure salary – used a park district credit card to pay for personal items at Toys “R” Us, Jewel Osco and Sports Authority, while also submitting expense reports for nongovernmental work.49

Cicero has also been subpoenaed by the U.S. attorney’s office for records of payments to vendors that donated to Larry Dominick’s campaign funds. From 2005 to 2016, You & Me Inc. received over $890,000 for items including lip balm, pens and pencil sharpeners imprinted with Dominick’s name, while the company donated $6,550 to Dominick’s election campaign, according to BGA. Another company, Lembke & Sons, received over $3 million in taxpayer-backed expenditures while donating more than $69,000 to Dominick’s campaigns.50

Patronage, nepotism and the blurring of lines between public service and politics appear to be the norm in Cicero. According to reporting by CBS Chicago, Dominick’s son is far from the only family member to have been on a government payroll. The town president’s ex-wife and at least eight of her relatives were also pulling in taxpayer-funded salaries at one point. What’s more, on at least one occasion, the president’s ex-wife publicly complained that her $70,000 salary was too low.51

The story of Cicero is also not without irony. First, the town president has had trouble managing his own money, in addition to mismanaging taxpayer funds. WGN-TV reported that Dominick faced foreclosure on two homes in 2014 after making zero payments for two years, despite earning a salary of $235,000 at the time,52 which is now down to just under $165,000, according to openthebooks.com.53 Second, Cicero appears determined to bolster an appearance of transparency while providing little information about the town’s finances in practice. The town’s website touts an award for “financial excellence” from the Government Finance Officers

Association for seven years in a row for its Popular Annual Financial Report.54 Ironically, this report also could not be found on Cicero’s website.

In order to ensure transparency and taxpayer confidence in Cicero and municipalities across the state, the Illinois General Assembly should immediately seek to revive the financial transparency reforms contained in the defeated HB 5522. In addition to the requirements that bill would have created, local governments subject to the measure should be required to annually post a full accounting of vendor disbursement records in a format that is useful for good-government groups and taxpayers seeking to learn more about government spending habits.

Conclusion

Taxpayers should not be treated like a piggy bank for state and local officials. Illinoisans are overtaxed and have little faith that their money is being well spent by the governments that receive it.

To restore taxpayers’ faith in government, politicians need to dramatically improve financial transparency and stop spending money on frivolous projects that don’t deliver value to taxpayers.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Endnotes

- Vincent Caruso, “Study: Illinois Home to Highest Overall Tax Burden in the Nation,” Illinois Policy Institute, March 15, 2018.

- Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill and Joe Tabor, “Pensions Make Illinois Property Taxes Among Nation’s Most Painful,” Illinois Policy Institute, Summer 2018.

- Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill and Suman Chattopadhyay, “Prime Working Age Illinoisans Leading the State’s Population Decline,” Illinois Policy Institute, June 21, 2018.

- Center for State Policy and Leadership at University of Illinois Springfield and NPR Illinois, “The 2018 Illinois Issues Survey,” September 26, 2018.

- See, e.g., Mark A. Glaser and W. Bartley Hildreth, “Service Delivery Satisfaction and Willingness to Pay Taxes: Citizen Recognition of Local Government Performance,” Public Productivity and Management Review 23(1), September 1999: 48-67; Benno Torgler, “Speaking to Theorists and Searching for Facts: Tax Morale and Tax Compliance in Experiments,” Journal of Economic Surveys 16(5), December 2002, 657-683; Bill Simonsen and Mark D. Robbins, “Reasonableness, Satisfaction, and Willingness to Pay Property Taxes,” Urban Affairs Review 38(6), July 1, 2003; Katharina Gangl, Stephan Muehlbacher, Manon de Groot, Sjoerd Goslinga, Eva B. Hofmann, Christoph Kogler, Gerrit Antonides, and Erich Kirchler, “’How Can I Help You?’ Perceived Service Orientation of Tax Authorities and Tax Compliance,” Public Finance Analysis 69(4): December 2013, 487-501.

- Divounguy, Hill and Tabor, “Pensions Make Illinois Property Taxes Among the Nation’s Most Painful.”

- Gallup, “Illinois Residents Least Confident in Their State Government,” February 17, 2016.

- Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, “Illinois State Budget, Fiscal Year 2019,” February 14, 2018.

- Illinois Policy Institute analysis of data from the 2012 U.S. Census of Local Governments.

- National Education Association, “Ranking and Estimates 2016-2017,” May 2017.

- Divounguy, Hill and Tabor, “Pensions Make Illinois Property Taxes Among the Nation’s Most Painful.”

- Illinois Policy Institute analysis of data from the U.S. Census Bureau, “2015 Annual Survey of School System Finances.”

- Jim Long, “Low Local Turnout Defines April Elections,” Illinois Policy Institute, April 13, 2015.

- 100th General Assembly, “House Bill 109.”

- Key words: promo, media, marketing, advert, ad, ads, brand, faceb, snapc, shirt, wristb, brochu, guide, mailer, flyer, poster, sticker, banner.

- Austin Berg, “College of DuPage President Gets Golden Parachute in Wake of Scandals”, Illinois Policy Institute, January 23, 2015.

- Austin Berg, “Ford Heights Ex-Mayor Charged with Stealing $150k from Village,” Illinois Policy Institute, August 23, 2018.

- Illinois Policy, “Top 10 Facts About Local Government Transparency”, October 20, 2014.

- Adam Schuster, “Bad Accounting Hides True Size of Illinois’ Budget Deficits,” Illinois Policy Institute, April 19, 2018.

- Adam Schuster, “State of Illinois Confirms New Budget is Out of Balance by $1.2B,” Illinois Policy Institute, August 21, 2018.

- Adam Schuster, “Illinois Senate Passes Cullerton Budget, Out of Balance by As Much As $1.5B,” Illinois Policy Institute, May 30, 2018.

- For definition and history of term, see Michael W. Drudge, “’Pork Barrel’ Spending Emerging as Presidential Campaign Issue,” America.gov, August 1, 2008.

- See Eddie Damstra, “New Illinois Budget Includes $224 Million for Obama Presidential Center,” Illinois Policy Institute, June 19, 2018; Mark Glennon, “Latest on Obama Center Fiasco: Federal Funding, Our WSJ Article, A Court Win and More,” Wirepoints, August 16, 2018.

- Adam Andrzejewski, “Replace Shirley Madigan on the Illinois Arts Council,” Forbes, July 19, 2017.

- The Liberty Justice Center is the litigation partner of the Illinois Policy Institute.

- Kirk Allen, “Watchdogs Sue Shirley Madigan’s Illinois Arts Council Agency for Public Records,” Edgar County Watchdogs, May 13, 2016.

- Adam Andrzejewski, “Replace Shirley Madigan on the Illinois Arts Council.”

- Ibid.

- 605 ILCS 30, Bikeway Act.

- Natalie, “Drive On to Boost Monarch Butterflies,” Chicago Sun-Times, August 10, 2016.

- Chris Jones, “Uptown Theatre Will be Restored: $75 Million Plan Unveiled for Grand Palace on North Side,” Chicago Tribune, June 29, 2018.

- Elizabeth Blasius, “Chicago’s Legendary Uptown Theatre to Come Back to Life,” Architects Newspaper, July 2, 2018.

- Ibid.

- HB3133, Illinois 100th General Assembly.

- Meet Chicago Northwest.

- Village of Schaumburg, “2016 Hotel and Convention Center Budget.”

- Joe Kaiser, “Rosemont to Build Taxpayer-funded Baseball Stadium,” Illinois Policy Institute, May 24, 2017.

- Joe Kaiser, “Illinois Taxpayers Paying for Billionaires’ Stadiums,” Illinois Policy Institute, June 2, 2016.

- Jonah Meadows, “32 Firearms Turned in at Evanston Gun Buyback,” Evanston Patch, June 10, 2018.

- City of Evanston Calendar, “Marshmallow Drop.”

- Bill Smith, “Massive Turnout for Marshmallow Drop,” Evanston Now, March 30, 2018.

- City of Evanston Calendar, “Marshmallow Drop.”

- “The Great Marshmallow Drop,” Evanston Round Table, April 4, 2018.

- National Recreation and Park Association Blog: “The 2017 NPRA Annual Conference Big Easy Preview,” April 30, 2017.

- “Lake County Employees Spent Thousands of Taxpayer Dollars on Food and Fun,” CBS Chicago, August 29, 2018.

- Bill Status of House Bill 5522, 99th General Assembly.

- Illinois Policy, “Top 10 Facts About Local Government Transparency, October 20, 2014.

- Illinois Public Act 097-0609.

- Andrew Schroedter and Dane Placko, “More Misconduct Alleged in Cicero,” Better Government Association, April 20, 2016.

- Andrew Schroedter, “Feds Resurface in Chicago,” Better Government Association, March 7, 2016.

- CBS Chicago, “Report: Cicero Payroll Loaded With Town President’s Wife’s Family.”

- WGN Web Desk, “Cicero Town President Faces Foreclosure,” July 5, 2014.

- OpentheBooks.com, “All State and Local Employee Salaries.”

- Town of Cicero, Illinois, “Town of Cicero Honored for Financial Excellence for the 7th Consecutive Year,” July 20, 2018.