Published Oct. 16, 2024

Illinois finds itself at a crossroads: will it empower minorities and poor people to unleash their potential, or will it perpetuate an inequitable status quo? For far too many Illinoisans, opportunity is unfairly and unnecessarily out of reach. Illinois ranks in the bottom ten among all states in social mobility and last among Midwest states by a substantial margin. The state’s inequitable occupational licensing laws are a key driver of this disappointingly low social mobility and lack of opportunity. It’s time to reform them by removing burdensome restrictions and making it easier to attain a license.

A staggering 24.7% of Illinois’ workforce needs a license to work and another 5% are required to be workforce certified. That’s about 1.6 million Illinoisans who still need the government’s permission to work the job they want and another 326,000 who need certification.

While the economic harms of these requirements are substantial and include 135,000 lost jobs and $15.08 billion in misallocated resources, the social harms are far greater.

Occupational licensing disproportionately hurts minorities, the poor, women, and young workers most of all. It disproportionately impacts formerly incarcerated individuals trying to reengage with society. It’s radically inequitable.

Two major negative consequences result from the state’s harmful occupational licensing laws. First, people who remain in Illinois, especially minorities and the poor, suffer from the unfair burden of occupational licensing. Second, those who can leave the state to seek opportunity elsewhere, do. Tens of thousands of our longtime neighbors leave our communities every year, doing irreparable harm.

Fortunately, Illinois state elected officials are coming to recognize the necessity of reforming the state’s inequitable occupational licensing laws. In 2024 alone, legislation passed to reduce licensing burdens for: military families moving across state lines, aspiring nurses, dentists, pharmacy clerks and counselors.

To become more of an opportunity state, Illinois needs to adopt an approach we call “equitable empowerment.” The reform agenda to support empowerment has five parts:

- Implement effective sunset reviews, which examine occupational licensing restrictions to ensure they are not more burdensome than necessary to protect public health and safety.

- Remove licenses for fields practiced safely in at least 10 other states that do not require such a license.

- Establish alternate pathways to licensing.

- Allow online asynchronous educational options.

- Adopt universal licensing recognition.

Introduction

Preventing minorities and poor people from prospering is inequitable. In a country nicknamed the “Land of Opportunity,” continuing to systematically disempower these historically underrepresented groups through bad policies and practices is unjust. The freedom to work and be economically and socially mobile are necessary to realize opportunity and are central to the American Dream. Institutions that disempower Americans by making it harder to earn an honest living, however, threaten to turn the American Dream into a mirage.

And yet, across America we unfairly and unnecessarily erect barriers to work for millions through occupational licensing. This drives inequality and harms the most vulnerable. Occupational licensing requires a government-issued permission slip to work in a particular field. In some fields, like medicine, it’s understandable that we’d want to ensure certain standards among practitioners to truly protect health. In many other fields, like community association management or cemetery customer service, the onerous educational or financial requirements imposed by licensing are incomprehensible.

Unfortunately, the number of fields that require an occupational license or certification has exploded. In the 1950s, about 4.5% of U.S. workers required a license to perform their jobs legally.1 While estimates vary, the Mercatus Center suggests that today up to one in three American workers need a license to work in their field.2 The Brookings Institution puts the number closer to 30%.3 And the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates it to be 24%.4

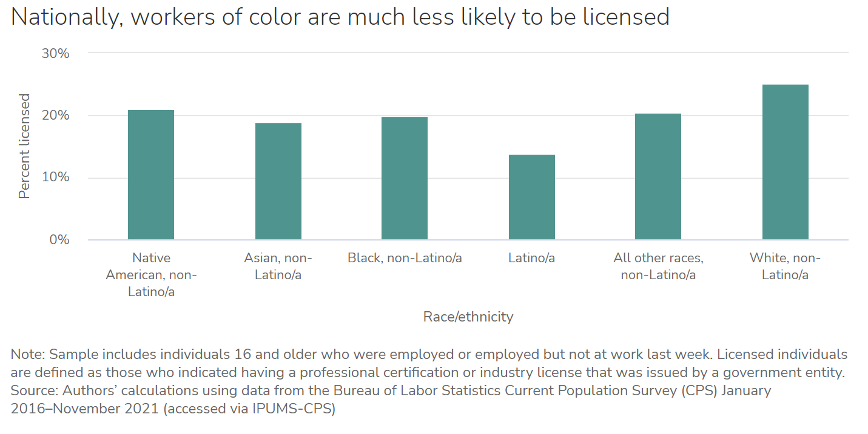

While this overregulation of work hurts everyone, it’s particularly bad for Black people, Latino people, and poor people. Black people are 5 percentage points less likely to be licensed than white people, and Latino people are 11 percentage points less likely to be licensed than white people.5

It is often expensive to get a license, creating a hurdle that’s especially tough for poor people to overcome. For example, it can cost tens of thousands of dollars just to gain permission to professionally trim someone’s hair. And it also takes a lot of time. Some licenses require up to four years of education. Occupational licensing robs people, particularly those without the luxury of time and money, of the chance to pursue their dream of working in a particular field, have a career they want, or simply the opportunity to simply provide for themselves and their family. That’s inequitable.

States differ in their degree of inequitable licensing laws. Some states make it difficult to make a living, others impose relatively fewer burdens. When a state has fewer burdens relative to other states, and its political leaders demonstrate a desire to reduce harmful regulatory burdens further, it is ripe for reform. Illinois is one such state.

Relative to other states, Illinois already places fewer burdens on people who want to work. A 2024 report released by the Archbridge Institute ranks Illinois eighth nationally for fewest barriers and licenses across 284 commonly regulated occupations.6 In a 2022 report, the Institute for Justice analyzed the burdens that states place on various low-income occupations: thirty-four states place more burdens on low-income people than Illinois for the surveyed occupations.7

While Illinois ranks well relative to other states, 24.7% of the workforce still needs a license to work. South Carolina has the lowest portion at 12.4%. Another 5% are required to be workforce certified.8 That’s about 1.6 million Illinoisans who still need permission to work in their chosen field, and another 326,000 who require certification.9 Illinois can do better.

Fortunately, over the past six years, Illinois’ political leaders have demonstrated a growing appetite to reduce barriers to empowerment. As Representative Carol Ammons, D-Urbana, chair of the Illinois Legislative Black Caucus, said:

“We need to remove some barriers in the licensing space because those barriers to licensing mean that a young person does not want to go back, necessarily, to school and pay all of this money for a position that’s going to pay them less than the cost of the certificate that they’re going to get.”10

In 2019, Illinois started to awaken the dormant sunset review process that audits occupational licensing laws.

Laws have changed to ease burdens for ex-offenders. While Illinois’ laws still lag behind other states, these reforms reduce the chances people will be denied an occupational license solely because they committed a crime. And in the 103rd General Assembly alone, legislation has been passed to reduce licensing burdens for: military families moving across state lines,11 aspiring nurses,12 dentists,13 pharmacy clerks14 and counselors.15

This dovetails with the emerging national consensus that occupational licensing laws need to be reformed. President Obama,16 President Biden17 and Senator Elizabeth Warren18 have all been outspoken on the issue. For example, a report from the Obama White House clearly states: “Lower-income workers are less likely to be able to afford the tuition and lost wages associated with licensing’s educational requirements, closing the door to many licensed jobs for them.”19 Among researchers, there is consensus for reform across a wide ideological spectrum, from left-leaning groups such as the Progressive Policy Institute20 and Brookings Institution21 to more libertarian groups such as the Institute for Justice22 and Cato Institute.23

At the heart of this reform agenda is a commitment to “equitable empowerment.” Empowerment is about people’s ability to unleash their potential. People need the tools required to succeed and can’t face unfair or unnecessary barriers to using these tools. Empowerment is important for the individual and the family, because it helps us thrive by making an honest living. It’s important for the community because everyone is better off when more people are empowered. For this to be equitable, everyone needs to be put into a position to succeed. When some people find themselves way behind because they aren’t able to acquire the necessary tools to unleash their potential, or when they face barriers to using them, they are in an inequitable situation.

Public policy can promote equitable empowerment by focusing on the creation and expansion of opportunity, and ensuring everyone is truly able to capitalize on opportunity and pursue happiness. Equitable empowerment ensures everyone has the tools necessary to rise above adversity. And it boosts economic growth and productivity. Crucially, equitable empowerment is not achieved by insisting on equal outcomes. This ends up reducing opportunity for everyone without helping the least well off. In fact, the best way to reduce disparities is to expand opportunity to as may people as possible.

A reform agenda for Illinois driven by equitable empowerment has five parts:

- Implement effective sunset reviews, which examine occupational licensing restrictions to ensure they are not more burdensome than necessary to protect public health and safety.

- Remove licenses for fields practiced safely in at least 10 other states that do not require such a license.

- Establish alternate pathways to licensing.

- Allow online asynchronous educational options.

- Adopt universal licensing recognition.

This report takes a deeper look at occupational licensing in Illinois, first demonstrating how it disproportionately disempowers many of Illinois’ more vulnerable populations. Then, in consideration of Illinois’ political landscape and growing appetite for occupational licensing reform, we propose several simple, common-sense strategies to help government officials better facilitate equitable empowerment. And we point toward future reforms that will help Illinois further burnish its image as a state fully committed to empowering people.

Social Harms of Licensing

Occupational licensing disproportionately hurts minorities and hurts the poor most of all. It also hurts women more than men, and young workers more than middle-aged and older ones. Lastly, it disproportionately impacts formerly incarcerated individuals trying to reengage with society. In other words, it’s radically inequitable.

Research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis details how occupational licensing disproportionately harms Asian, Black, American Indian and Alaskan Native workers.24

They are 6, 5, and 4 percentage points less likely, respectively, to be licensed than white workers. The disparity between Latino and white workers is even higher at 11 percentage points.25

One way licensing laws hurt minorities more, according to the American Enterprise Institute, is “by setting licensure standards that required more formal schooling than most black people attained or by discriminatory application of licensure standards.”26 And even in groups with similar levels of education, the same Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis study shows workers of color are underrepresented among licensed workers.27

Some research suggests occupational licensing has unsavory discriminatory origins. George Mason University law professor David Bernstein writes, “white interest groups used occupational licensing laws to stifle black economic progress. While generally not Jim Crow Laws per se, the laws were used both in the South and the North to prevent Black people from competing with established white skilled workers.”28 Even “facially neutral licensing laws,” he contends, “have a history of being used against racial minorities.”29

Barber regulations are one poignant example of a historically discriminatory license. Research from the Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation at West Virginia University shows that in 1890, Black people accounted for 21% of all barbers. By 1930, that was down to 9%. One key mechanism the Journeyman Barber International Union of America used to erect barriers for Black people to become barbers was licensing. Arkansas established licensing requirements for barbers in 1937. The result? The number of black barbers in Arkansas plummeted by 41% from 1930 to 1940.30

We consider next how occupational licensing hurts poor people.

Illinois specifically licenses 41 low-income professions surveyed in License to Work, a report from the Institute for Justice.31 This licensing costs Illinoisans an average of 234 days lost to education and experience. This includes professions like Sign Language Interpreter and Auctioneer. Cosmetology is a particularly egregious example. According to another report by the Institute for Justice, while the average cosmetology school tuition nationally is already expensive at $16,000, it’s $17,658 in Illinois.

That cost is inextricably tied to the government-mandated education requirements, but the value of that involuntary education for anyone who wants to enter the field is highly questionable. The median annual wage is $27,040. What’s more, only 29.4% of students graduate cosmetology school on time, 51.4% graduate within 18 months, and only 53.3% graduate within 24 months.32

Research shows eliminating occupational licensing would reduce the income gap between the richest and poorest by up to 2-4%, and overall income inequality by up to 7%. One reason for this is that strict labor regulations discourage workers from going into occupations, and “these effects are most keenly felt by workers already more likely to be financially disadvantaged.”33 Research from the Obama Administration showed the costs of obtaining a license prevent low-income workers from accessing many professions.34

Cato Institute research explains that poor people and younger workers are especially harmed by the reduced workforce mobility and barriers to work and advancement created by occupational licensing. Other research explains that occupational licensing can further restrict job opportunities for workers whose options are already limited, which is especially true for poor and minority workers.35

Licensing drives racial income inequity. The greatest effects on earnings inequality were among Black people, foreign-born Hispanic people and women.36 Other research shows licensing requirements increase inequality for Black people the most.37

Licensing makes it harder for low-income workers to start a business. A report from Arizona State University shows, “the higher the rate of licensure of low-income occupations, the lower the rate of low-income entrepreneurship,”38 killing the initiative of people trying to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps.

Licensing also hurts poor people by raising the prices of goods and services. A study from the Brookings Institution states that consumers pay as much as 15% more for services when an occupation is licensed. This hurts the poor the most because unlike wealthy people, they are hit hard by even small price increases, which can send their already strained budget into the red.

Women are harmed more than men by occupational licensing laws. A report from the Knee explains many professions in which women are a majority are often licensed. Examples include:

- Daycare provider

- Lactation consultant

- Cosmetologist

- Hair braider

- Makeup artist

- Shampooer

- Skincare Specialist

- Eyebrow Threader39

The same research on income inequality found occupational licensing increases such inequality for women.40

Young workers also are set back under occupational licensing. Morris Kleiner, the foremost researcher in occupational licensing, and Evan Soltas found in a study that licensing delays entry of younger workers into occupations. In highly licensed occupations, employment among workers 25 and younger falls by 48% on average.41 An analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data found those ages 18 to 35 without a college degree or license experienced much higher unemployment and lower wages. They earned 13% less than licensed workers.42

Formally incarcerated individuals often suffer much more under occupational licensing. This is because they are typically forbidden from entering a variety of professions, even if the crime they committed is completely unrelated to the field in which they want to work. This unfairly crushes the hopes of people who want to get their life back on track.

Research has shown heavier occupational licensing burdens are linked to higher rates of recidivism when compared to states with lower barriers to entry, because steady work helps formerly incarcerated individuals reclaim their lives.43

Fortunately, as part of the reform efforts we mentioned earlier, Illinois has made some improvements to help those who have been previously incarcerated. Like many other states, Illinois has a “good moral character” provision in its requirements for licensure, which was historically used to deny licenses to ex-offenders, even if the crime was entirely unrelated to the occupation. Illinois law now states that a license cannot be denied on lack of good moral character if that finding “is based solely upon the fact that the applicant has previously been convicted of one or more criminal offenses.” The law also requires consideration of mitigating factors, including but not limited to:

- Whether the crime was related to the occupation.

- The time that has passed since conviction/release from prison.

- Whether the applicant previously had a license and wasn’t disciplined.

- The applicant’s age when they committed the crime, and evidence of rehabilitation.44

Burdensome licensing requirements also pushes people into the “underground” economy. Some people will forgo getting a license and nonetheless work in a field “illegally.” This is harmful because these people lack the basic protections afforded to them through “legal” work like insurance, benefits, and simple legal recourse for anything that goes awry.

The case of hair braiding in Louisiana and Mississippi is illustrative. Hair braiding is done almost exclusively for and by Black people. The states have the same percentage of Black people – 12.4% – according to 2020 Census Bureau data. Louisiana’s population of 4.65 million is 57% larger than Mississippi’s population of 2.96 million.45 Mississippi requires zero hours of training and has over 6,700 registered braiders. Louisiana requires all hair braiders to complete over 500 hours of training as a private cosmetology school.46 In all likelihood, there are thousands of Louisianans forced to braid hair in the underground economy. That’s unfair to them, and threatens them with legal and economic harms.

Economic Harms of Licensing

The economic harms of occupational licensing are also massive. Licenses put sand in the gears of the economy, making it hard for individuals and businesses to innovate and grow. That is exactly what happens in Illinois.

Illinois’ occupational licensing regime is economically harmful. In 2018, Kleiner estimated the cost of licensing in Illinois at 85,973 jobs and $9.6B in misallocated resources across the economy, from individuals to businesses to consumers.47 Adjusting those numbers for 2024 to account for the growth both of licensing and Illinois’ economy, licensing accounts for approximately 135,000 lost jobs, and $15.08 billion in misallocated resources.

With 328,000 unemployed people as of June 2024 and the 2nd highest unemployment rate in the country of 5.2% as of July 2024,48 Illinois doesn’t need more barriers preventing these people from working. The report also finds a deadweight loss, meaning lost economic efficiency and welfare, of $388.7 million annually. As of June 2024, Illinois reports 1.597 million active licenses in a labor force of 6.517 million.49 What’s more, relative to other states, Illinois’ burden increased from 2017 to 2022.50

Occupational licensing impairs occupational mobility by making it much harder for people to switch jobs. Individuals who work in a licensed profession are 24.1% less likely to change professions. Licensing could account for nearly 8% of the decline in monthly occupational mobility since 2000.51 People whose current jobs aren’t working out or are simply looking for a change are discouraged from moving across professions, and businesses have a harder time filling job openings.

Occupational licensing reduces geographic mobility too, meaning it’s harder for people to move across state lines. Research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis found that “the between-state migration rate for individuals in occupations with state-specific licensing exam requirements is 36% lower relative to members of other occupations.”

By contrast, workers in occupations with national licensing exams show no negative interstate migration effects.52 With a massive outmigration problem of tens of thousands of people leaving every year, the last thing Illinois needs to do is make it even harder for people to move here. Universal licensing recognition, a policy recommendation we discuss below, would help address this problem.

Further research found high occupational licensing costs reduce sales in self-employed firms.53 Since 6-11% of U.S. households have at least one self-employed member,54 the negative impact felt by these individuals and families is significant. Self-employment has many benefits, as a source of income for poor households during economic downturns, and increasing labor productivity.55 Government-created hindrances to self-employment are inequitable.

And to top it all off, licensing fails to improve quality. The Obama White House Report states, “with the caveats that the literature focuses on specific examples and that quality is difficult to measure, most research does not find that licensing improves quality or public health and safety.”

Kleiner echoes this sentiment: there is “little evidence to show that the licensing of many different occupations has improved the quality of services received by consumers.” At the same time, “in many cases it has increased prices and limited economic output,” meaning all these unnecessary costs don’t even result in the purported benefit.56 That means families and the economy are hurt by licensing for no reason.

Illinois’ Growing Appetite for Licensing Reform

Over the last five years, Illinois’ political leaders have joined the emerging national consensus in favor of reducing licensing burdens. They need to capitalize on this momentum to enact additional reforms that will empower more people.

When Gov. J.B. Pritzker took office in 2019, his administration awakened a dormant process that audits occupational licensing laws called sunset reviews. Sunset reviews periodically examine laws to ensure they’re still necessary in their current form. Many occupational licenses are not. Even though the enabling act for sunset reviews took effect in 1979,57 the agency responsible for sunset reviews has no record of a single review being performed during from 1979 to 2019.58 The Pritzker Administration’s vitalization of sunset reviews indicates it acknowledges the importance of occupational licensing reform and is willing to take action.

The General Assembly passed legislation in 2022 to create the Comprehensive Licensing Information to Minimize Barriers Task Force. Its purpose is to “better support the General Assembly in revoking, modifying, or creating new licensing Acts” by providing an analysis on occupational licenses for low to middle income jobs.59 The task force’s report will be published later this year.

In the 103rd General Assembly alone (2023-2024), legislation has been passed to reduce licensing burdens for: military families moving across state lines,60 aspiring nurses,61 dentists,62 pharmacy clerks63 and counselors.64

State legislators also recognized the need to speed up license-processing time. One barrier to this was the outdated software used by the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, the agency that oversees 1.2 million of Illinois’ 1.6 million licenses.65 Their software was from the 1990s, resulting in unnecessarily long wait times for people who already fulfilled the requirements for licensure.66 After blowing past two deadlines, the agency finally announced a signed contract with a new software vendor on August 6, 2024. This reform alone should significantly reduce procedural burdens and streamline the process for people applying for a license or renewal.67

A complete list of passed licensing reform legislation from the 103rd General Assembly is included in Appendix B.

Countless other bills were introduced but never passed, most sponsored by Democrats, showing bipartisan support for occupational licensing reform. There were multiple attempts each to institute fee maximums,68 recognize licenses from other states69 and make requirements less burdensome for beauty industry workers.70

The reforms that have passed are cause for celebration. And the bills that were introduced but didn’t pass should be reintroduced when the General Assembly reconvenes. In Appendix C we provide a shortlist of bills that we recommend be reintroduced.

In what follows, we outline an agenda of common-sense reforms that will help Illinois gain further momentum and become a leader in licensing reform, driving towards equitable empowerment.

Implement Effective Sunset Reviews

Many states, including Illinois, have a sunset review process. This process regularly reviews occupational licensing restrictions to ensure they are not more burdensome than necessary to protect public health and safety. The trouble in Illinois is that while the state’s sunset review process was codified into law on September 22, 1979, it laid dormant until 2019; and even since attempting to awaken it, the state still lacks an effective review process. Implementing an effective process is perhaps the single most important reform Illinois can enact to ensure occupational licensing in the state is fair and equitable. Crucially, since Illinois already has a sunset review process on the books, this tool exists for elected officials to eliminate harmful and unnecessary licenses.

To understand how to reform the process, we must first look at how the process currently is structured in state law.

Broadly speaking, the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget (GOMB) is only supposed to regulate professions if they pose a significant risk to someone’s safety or health. The legal requirement is:

That no profession, occupation, business, industry or trade shall be subject to the State’s regulatory power unless the exercise of such power is necessary to protect the public health, safety or welfare from significant and discernible harm or damage. The exercise of the State’s police power shall be done only to the extent necessary for that purpose.71

All regulation of occupations, and thus all sunset reviews, are supposed to occur in this context.

Under the Regulatory Sunset Act, which was originally enacted in 1979, each law regulating an occupation has a date on which it automatically sunsets, or expires, unless the General Assembly acts to extend the law by pushing that date back. Prior to the automatic expiration date and the General Assembly’s decision of whether to extend the act, GOMB is supposed to prepare a report (a sunset review) including recommendations on a) whether the act should be extended or allowed to sunset and b) if extended, how it should be modified. The General Assembly then is supposed to draw on those recommendations in making their legislative decisions.72

The Regulatory Sunset Act’s delineation of what goes into a sunset review is split between two sections in the act, Section 6 and Section 7.

From 1979 to 2023, the criteria of Section 6 primarily regarded the performance and operations of the regulatory agency governing the act under review. In 2023, Public Act 102-984 was passed and amended the criteria. We will discuss those changes later.73

Section 7 is titled “Additional criteria,” which includes evaluating the current regulations in the following manner: whether their sole purpose and effect is to protect the public, a cost-benefit analysis and whether there are less restrictive alternatives.74 The guidelines under Section 7 are in accordance with recommended best practices for states in the Obama White House report.75 The only changes of P.A. 102-984 to Section 7 were adding a list of potential less restrictive alternatives to consider.76

Even though the enabling act for sunset reviews took effect in 1979, GOMB has no record of reviews being performed prior to 2019.77 It is not clear what exactly accounts for this. When GOMB first awakened the process in 2019, however, the reviews they published were substantially incomplete. All 39 occupation-related sunset reviews published between 2019 and 2023 evaluated the criteria listed under Section 6. But none of them evaluated the criteria listed under Section 7.78 That is problematic because these important criteria offer another lens through which to view whether regulation is truly necessary.

According to the Obama Administration Report, in an ideal sunset review “analysts would estimate the costs and benefits of the licensing proposal or legislation in a careful and thorough manner, comparing licensing with alternative regulatory options, as well as legislative inaction.”79 The reviews GOMB published between 2019 and 2023 failed to do this, thereby handicapping the General Assembly’s ability to make fully informed decisions on occupational licensing laws.

At the beginning of 2023, several changes to the Regulatory Sunset Act under Public Act 102-984 were enacted.80 Changes to Section 6 included the addition of more explicit considerations regarding:

- If there is evidence of significant and discernible harm that came from the occupation’s scope of practice.

- If all qualifications required for the occupation are necessary to protect the public.

- A comparison of expected salary versus costs for people wanting to become licensed.

- Burdens for people of historically disadvantaged, foreign, or with criminal backgrounds.

For Section 7, a specific list of less restrictive methods of regulation was added. Taken together, these changes are supposed to make the sunset review more rigorous.

At the time of this report’s publication, only two sunset review reports have been published by GOMB since the changes under P.A. 102-984 went into effect in 2023. These reports reviewed requirements for genetic counselors and shorthand reporters. On the plus side, they were more robust than any of the 39 reports published between 2019 and 2023. There was a clear, demonstrated effort to cover some of the changes made under P.A. 102-984. Unfortunately, neither one recommends allowing the license to sunset, or even reducing the burdens they create. In the next section, we make the case for why the regulations for these two professions, among many others, should be allowed to sunset.

One reason for the ineffective nature of these reviews is they still largely fail to consider the criteria of Section 7 and some of the criteria under Section 6.81 Notable criteria which the new reports still fail to consider include:

- Whether the State has the right to impose the current regulations.

- Whether the current regulations’ sole purpose and effect is protection of the public.

- If there is evidence of significant and discernible harm that came from the occupation’s scope of practice.

- A comparison of expected salary to costs for people wanting to become licensed.

- If there are less restrictive alternatives that could still adequately protect the public.

- A cost-benefit analysis of current regulations.

If GOMB were to have included these changes, we would expect sunset reviews to identify the burdens in these – and many other fields – to be unnecessary and unduly prevent people from obtaining a license. The legislature would then be much more inclined to ease these burdens.

While steps are being taken in the right direction, sunset reviews as they are currently performed by GOMB are still not robust enough to adequately inform the General Assembly. That means further reforms are necessary to ensure a robust process.

One common sense reform is to ensure GOMB simply follows its mandate: full consideration of all the criteria listed in both Section 6 and Section 7 of the Regulatory Sunset Act. To do this effectively, GOMB needs a framework for equitable cost-benefit analysis. We provide one in the following table:

For example, research from the Illinois Policy Institute identifies cosmetology as a field in which the comparison of salary to costs raises questions about the burden imposed by licensing requirements: “In Illinois, obtaining a cosmetology license requires attending 1,500 hours of schooling, which on average cost $17,658 statewide in 2019. Factor in the 1,500 hours’ worth of lost wages assuming Illinois’ minimum wage of $14 per hour, and you reach a total cost of $38,658. The median wage for a cosmetologist in Illinois in 2019 was only $27,040.”82

Such licensing erects an often-insurmountable barrier for minorities and poor people. The salary they could earn simply may not justify the costs associated with the licensing requirements. GOMB is required to spell out this cost-benefit information for lawmakers, and they need to do so. This would help them more easily identify opportunities to reduce the burden felt by people of low-income and minority backgrounds. For specific mechanisms that can do this, lawmakers should refer to the list of less restrictive alternatives now outlined in Section 7 of the Regulatory Sunset Act.

Moreover, sunset reviews should examine the licensing structures of other states, particularly those who have less stringent or no license requirements at all. The licensing structures of those other states should serve as a model for Illinois to lessen burdens for its residents while still protecting their health and welfare. When other states don’t license an occupation, it typically indicates they are able to successfully protect the public without the same restrictions that potentially harm people of low-income and minority backgrounds. In the following section, we offer a more in-depth look at how Illinois can follow more equitable models of other states. The additional criteria of considering the licensing structures of other states are something that should be legislated into the Regulatory Sunset Act and executed by GOMB without significant additional burden. In Appendix A, we offer a model policy for this.

Illinois also needs mechanisms to ensure sunset reviews receive proper attention from legislative committees. The reports are simply filed electronically to the entire General Assembly through a general online reports portal, with copies sent to each of the four leaders of the General Assembly.83 These reports easily can be lost in the large swathes of reports and other information elected officials and their staff receive.

Procedural reforms are simple and common-sense on this front, too. Currently, legislation concerning occupational licensing is filed in the Illinois General Assembly, then typically goes through the Licensed Activities Committee in the Senate and/or the Health Care Licenses Committee or Occupational Licenses Subcommittee in the House. While it is impossible and obviously undesirable to force elected officials and their staff to read sunset reviews, it should be required that the reports are specifically sent to the committee members in addition to the general portal, which is an online database for every report sent to the General Assembly.84

We recommend relevant committees hold subject matter hearings when sunset reviews are published. Holding subject matter hearings on sunset reviews would also promote public participation in the process and help legislators understand the issue better. This follows the successful example of other states like Nevada and Ohio.

The legislature also needs to ensure it files legislation about extending or modifying a licensing requirement only after receiving and considering the sunset review report. Oftentimes, this happens in the reverse order, making the sunset review useless. For example, the two sunset reviews published after the passage of P.A. 102-984 both reference the fact that legislation to extend and modify their respective acts had already been introduced.85

In order to ensure legislators have access to sunset reviews before extending or modifying licenses, the legislature should impose a deadline on GOMB to publish reviews before the beginning of a legislative session, giving legislators more time to read the reviews and write legislation accordingly. We provide a mechanism for legislating this deadline in Appendix A.

Texas,86 Nevada,87 Ohio88 and Idaho89 also have legislative committees dedicated to hearing sunset reviews. Having a formal, legislated mechanism for these sunset reviews to be read and discussed by members of the legislature enables these states to make more-informed decisions regarding occupational licensing.

Texas’ process is the most robust. In 2021 “the TDLR Sunset bill eliminated 29 unnecessary [occupational] licenses; streamlined the regulation of barbers, cosmetologists, and driver training providers; and directed [the Texas Department of Licensing and Regulation] to be more data-driven in its inspection and enforcement processes to focus its resources on the highest risks to the public.”90 That all happened in just one year. And it’s the norm: “80 percent of Sunset recommendations to the Legislature have become state law” in Texas since 2001.91

Texas’ process of bringing together legislators, members of the public and staff to perform reviews enhances their process, too.92 Here is what it looks like:

- Staff first conduct research and develop recommendations to publish in a staff report.

- The Sunset Commission conducts a public hearing where the staff report is presented and the relevant agency responds. Public testimony and written comments are also allowed.

- The Sunset Commission holds a second meeting to vote on which recommendations to make to the state legislature.

- The Commission also can issue management directives to the regulating agency to address discovered inefficiencies.

- The legislature considers the Sunset Commission’s recommendations before proceeding with legislation as normal.

One further reform Illinois should consider once it establishes an effective sunset review process is to establish an effective sunrise review process. Sunrise reviews occur at the beginning of the legislative process. These reviews study newly proposed occupational licenses and new regulations for existing licenses. They examine whether these new restrictions are necessary in the first place. They generally recommend applying the least restrictive method of regulations. Fourteen states already have some form of sunrise reviews.93

Look to Other States to Promote Equitable Rules

Illinois can learn how to create equitable rules by looking at what burdens other states don’t place on residents. We recommend two simple best practices in this section for crafting fair licensing requirements.

First, if an occupation is practiced in other states without a license, then there is good reason to think a license is not necessary to protect public safety. According to the Obama White House report, “Estimates suggest that over 1,100 occupations are regulated in at least one State, but fewer than 60 are regulated in all 50 States, showing substantial differences in which occupations States choose to regulate. For example, funeral attendants are licensed in nine States and florists are licensed in only one State.”

That’s over 1000 occupations practiced safely without a license in at least one state. The specific guideline we recommend for Illinois on this front is: if an occupation is licensed in fewer than ten states and licensed in Illinois, Illinois should remove this inequitable licensing requirement.

Many of the jobs in the table above do not carry significant and discernible public health risks, meaning they are prime opportunities for reform. It’s also important to note that this list is not exhaustive. For example, research from the Knee Center has identified other professions that are – rather oddly – licensed in Illinois, but not many other states, such as Hypnotist and Sanitarian in Training.95

The second reform principle we recommend is: If a profession is practiced safely in another state with fewer licensing requirements, then Illinois should reduce its requirements to make them less burdensome and unfair, ideally bringing them in accordance with the less onerous restrictions of the other state.

Consider requirements to become a barber. In Illinois, barbers must obtain 1,500 hours, a full year, of education in Illinois.96 By contrast, New York has state-accepted barber education programs with only 360 hours.97 That’s a year of coursework in Illinois, versus only 3 months in New York.

These principles can inform the regulatory process in two ways. First, when it is time to conduct a sunset review for a field, the state should consider whether and how it is regulated in another state. Second, since some acts are not scheduled for sunset review until 2032,98 lawmakers may also introduce legislation to repeal/modify unnecessary acts before then.

Using methodology from the Institute for Justice, we estimate that this reform alone would open up more than 2,400 jobs. It would also prevent $11 million in deadweight losses and save more than $272 million in misallocated resources.99

Policy Recommendations

With the right policy reforms, Illinois can empower workers and become a leader in reducing the burdens of occupational licensing. We identified two important reforms: enhancing the state’s sunset review process to make it robust and looking at other states for proof that professions can be practiced safely with fewer or no licensing requirements.

In this section, we recommend three simple, common-sense reforms to empower more workers:

- Build apprenticeships that result in licensure

- Offer an online education alternative

- Institute universal license recognition.

First, Illinois needs to expand and innovate its career and technical education to allow people to get an earlier start on finding a career, save a substantial amount of money and avoid unfair barriers like being forced to attend expensive for-profit schools to attain a license. A particularly promising way to do this is through apprenticeships.

Specifically, Illinois should enact two reforms centered on expanding opportunity through apprenticeships: First, allow Illinoisans to earn a license through apprenticeships that provide education and training outside of for-profit schools. This would open up new pathways to opportunity. Second, expand secondary school apprenticeship programs to licensed fields like cosmetology that culminate in earning an industry- and state-recognized license upon meeting program requirements.

Apprenticeships are a proven model for empowering people through work by getting them tangible skills. According to research from the Center for American Progress, apprentices earn higher wages, receive education while taking on little or no debt, and often find immediate full-time employment that pays well.100 A report from the Progressive Policy Institute showed individuals who complete an apprenticeship earn an average salary of $77,000, far above the $55,000 average national salary.101

Let’s first consider expanding apprenticeship-to-license opportunities. Currently, to become a barber, cosmetologist and many other aesthetic fields, individuals can only earn their approved credentials through for-profit trade schools. That creates big, unfair barriers to poor and minority workers like an average of over $17,000 in tuition.

Apprenticeships are paid all the way through. Rather than forgoing a paycheck by enrolling in trade school and having to get a part-time or full-time job on the side, you can learn-while-you-earn with an apprenticeship. Apprentices are paid on their pathway to opportunity.

Instead, Illinoisans also ought to be able to earn an occupational license by training directly with someone in that trade. Fortunately, House Bill 4617, introduced in January 2024, would do precisely that in some fields. It amends that Barber, Cosmetology, Esthetics, Hair Braiding, and Nail Technology Act of 1985.

It would provide someone the opportunity to earn a license as a cosmetologist by completing “an online course approved by the Department of Financial and Professional Regulation and 750 hours of hands-on training supervised by a licensed cosmetologist extending over a period of not less than eight months nor more than seven consecutive years and the person has completed the other requirements for licensure under the Act.”102 Connecticut has a similar pathway for barbers.103

This approach offers the opportunity to learn over a longer period, up to seven years. That’s crucial for people who cannot quit their full-time job to attend school for 12 months. Simply by working as an apprentice on Saturdays, alongside their full-time job, someone would complete the required training in less than two years.

Numerous other states have passed bills along these lines in recent years that are even broader. In 2021, Idaho passed House Bill 178. The bill “requires state licensing authorities to issue a license if a person serves an apprenticeship, pays the required fees and passes a certification exam, if one is required. If the licensure authority denies a license or deems an apprenticeship not up to their standards, they must explain why in writing. Licensure authorities also cannot create requirements for apprenticeship applicants which are more onerous or restrictive than those for applicants who attend a school.”104

In 2022, Iowa changed its regulatory code to require the board to “grant a license to a person who completes an apprenticeship program in the relevant occupation or profession and submits an application.”105 These changes also stipulate that someone who completes training through an apprenticeship cannot be required to pay greater licensing fees or earn a higher score on an educational requirement than someone who completed an educational program.

Alabama106 and North Carolina107 passed similar legislation in 2019.

To empower poor and minority Illinoisans, the most equitable approach is to expand HB4617 to all licensed occupations as these other states have done. Upon completing the apprenticeship, passing an exam and paying fees, individuals should have a license to work in a field. We include a model policy in Appendix A.

Second: Create secondary school apprenticeships in currently licensed occupations. Offer apprenticeship programs in licensed fields like cosmetology, pharmacy tech and emergency medical services. Upon completing the program, students would receive an occupational license in the field. This would showcase Illinois as a leader and innovator in equitable empowerment.

This proposal would expand the benefits of apprenticeship programming to a wider range of industries that are currently off limits to many minority and poor Illinoisans because they don’t have the time and money to get an occupational license.

Illinois has the infrastructure necessary to expand these programs. The state has a total of 435 active apprenticeship programs in select secondary schools as of August 2024.108

But the Illinois Future of Work Task Force Report shows Illinois only spends $34 million annually on secondary school apprenticeships.109 Of the 611,732 students in Illinois secondary schools in 2022, only 22,713 were career concentrators.110

Illinois needs to shift resources to expand these programs to licensed occupations and many more schools. Increasing taxes is an undesirable way to fund these training programs because high taxes are driving people out of Illinois. Of the 117,000 Illinoisans moving out in 2022, the most recent year for which Census data are available, 97% moved to lower-tax states.111

The best place to reallocate funding is from universities. Unfortunately, Illinois’ state universities are not serving students well. According to the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, Illinois has the worst return on investment for public undergraduate programs in the Midwest. The median return on investment for a student is only $112,154. South Dakota, Iowa and Minnesota are nearly double at more than $214,000. Illinois also has the highest share of undergraduate programs with a negative ROI, 29.9%, in the Midwest. Almost 1 in every 3 four-year public undergraduate programs in Illinois will do more financial harm than good for their students.112

If the state were to reduce university funding from $2.6 billion to $2.5 billion and allocate the $100 million to secondary school apprenticeship programs, this would be sufficient funding to expand apprenticeships into currently licensed fields. This is triple the budget of $34 million that funds 22,713 career concentrators. This would open programs up to tens of thousands of Illinoisans, the costs of training across apprenticeship fields is similar. It would also allow for robust marketing because raising awareness is key.

An easy area for cost savings is administration. An article in Forbes explains, “Between 1976 and 2018, full-time administrators and other professionals employed by those institutions increased by 164% and 452%, respectively. Meanwhile, the number of full-time faculty employed at colleges and universities in the U.S. increased by only 92%, marginally outpacing student enrollment which grew by 78%.”113 Increasingly, this means disproportionate sums of money at colleges and universities aren’t going to faculty or students or departmental programming but rather to administrators who keep increasing in number and as a portion of overall spending. That’s true in Illinois, too. From 2005 to 2015 alone, the number of full-time equivalent administrator positions at Illinois public universities increased by 26% while full-time equivalent fall student enrollment dropped by almost 3% over that time.114

This also contributes to increasing tuition costs. Those increasing costs drive inequity by putting college out of the reach of more low-income students. While increasing staff in workforce preparedness might be understandable, expanding staff in areas like entertainment and intramural sports seems harder to justify when those funds can be used much more effectively to empower people to have careers.

The massively unequal funding between colleges and universities on the one hand, and vocational training on the other, contributes to the stigma of vocational training as inferior to going to college. If a student’s goal is to have a well-paying career, they can earn an average of $22,000 more per year by completing an apprenticeship. Many students are completely unaware of the benefits of vocational training or decide against pursuing it because they’re told it’s better to go to college. Starting to balance the funding between the two will help address this problem.

But that’s not the only way in which education requirements can be improved. Most people don’t live a simple, sequential, synchronous life where they can calmly pursue things like an education without distraction or complication. When educational requirements can’t accommodate their needs, they are inequitably denied opportunity. If you have a full-time job, a family, or face a wide range of other life situations that get in the way of your ability to work toward a license uninterrupted, you’re forbidden from entering a field unless asynchronous options exist.

Hence the next reform recommendation: Allow online asynchronous educational options. This would open opportunities to people who can’t dedicate consecutive large chunks of time – including months or years – to focus solely on earning a license.

Currently most state-approved education programs are scheduled and in-person, which presents barriers for people who must also work another job to support themselves and/or live in rural areas. These programs don’t need to be in-person and scheduled to impart the knowledge necessary to protect public health. In many cases, a textbook suffices for students to acquire the pertinent knowledge. What’s more, in some cases, classes don’t even add any value above the textbook. As one student said, “All they did was hand you a book. They don’t care what you do, as long as you finish [filling in] that book.”115

The equitable solution is to offer online and asynchronous educational programming for any non-hands-on requirements like learning rules and standards. This would reduce travel burdens and allow aspiring workers to complete the curriculum on their own time, making things easier for the many people who must juggle commitments other than attending these programs. It also would not preclude people from taking in-person courses.

Illinois already allows online options for renewal (continuing education) requirements.116 Wherever possible, that should be expanded to initial licensure requirements as well. Fortunately, Texas and Virginia provide simple models for how to do this. The states have a robust list of online options for residents who want to take training courses.117 Indiana provides an even more enhanced model where aspiring licensees in some professions can fulfill their education requirements online through the University of Indianapolis.118 We also provide model legislation for approving online programs in Appendix A.

The third policy reform we recommend in this section is to adopt universal licensing recognition. In its broadest form, this means the state grants a license to workers who are licensed in good standing in another state without criminal complaints against them. According to research from the Knee Center, through July 2024, 26 states have enacted some form of universal license recognition.119 While the extent and scope of the reforms in these states varies, the most desirable option is full universal recognition because it creates more equitable opportunities for everyone.

Universal recognition promotes equity and opportunity because it removes a huge barrier to people either moving or engaging in their licensed profession once they do move. Since they have already completed the requirements, and earned a license, there is no need for them to go through that process again. Data suggest universal licensing recognition increases employment by almost 2 percentage points in occupations with low license portability such as barber, cosmetologist, or electrician.120

One group who suffers particular harm without universal recognition is military spouses who have an occupational license. Individuals don’t serve our nation alone, their families make sacrifices too. It’s unfair to prohibit spouses from earning a living simply because their family has to move every two to three years to serve. Many states have corrected this injustice by carving out an exception for military spouses to permit them to practice after having earned a license elsewhere. Fortunately, Illinois is among them.

Illinois has two ways that effectively address this problem: expedited license application processing and a military portability license. First, Illinois law has required the Department of Financial and Professional Regulation to have a military liaison since 2019. Initially, the liaison’s responsibilities were to work with military families and ensure their license applications were processed within 60 days. That deadline has since been changed to 30 days. Second, in July 2024, Gov. Pritzker signed P.A. 103-708, adding the oversight of military portability license to the liaison’s responsibilities.121 The military portability license is a separate path for active military service members and their spouses licensed in another state, allowing them to completely bypass the requirements other Illinois residents face.

These good reforms beg the question: If military spouses they can practice in Illinois safely, why not everyone else? Why stop there? The case for universal licensing reform is clear and compelling. Illinois can join the growing number of states expanding equity in this manner.

Fortunately, a bill to do precisely this was introduced last legislative session. House Bill 5608 would recognize occupational licenses or certifications in good standing from other states that would have satisfied the requirements in Illinois. The simplest thing to do is reintroduce and pass this legislation.

Barriers to reform

Some groups often possess lobbying power and legislative influence that dwarf those held by Illinoisans.122

One understandable concern comes from already-licensed professionals. Their objection to reducing or removing licensing requirements is: “How is it fair that I invested time and money getting a license, and now that’s no longer necessary?” The best response is: As unfortunate as it is that you suffered under unfair and inequitable requirements, we should not perpetuate them any longer than necessary. We can only correct the harms going forward, not rectify past unfair practices.

Another concern from already-licensed professionals is the desire to reduce competition. After all, without a license, it is illegal to enter a licensed profession. Indeed, occupational lobbies have a history of trying to artificially restrict entry into their professions: Institute for Justice research has found 83% of proposed regulations are initiated by lobbies,123 even though most of the time an independent audit finds that no new regulations are necessary.124

The desire to reduce competition in all occupations is unjust and inequitable. It erects a massive barrier for poor people and minorities trying to enter a field.

For-profit vocational schools, along with their lobbyists, present one huge barrier to an equitable licensing code. For-profit schools have an understandable, albeit unfair, objection: removing licensing burdens would result in fewer students, and thus less revenue. As people learn trades without paying for an education, either by pursuing an apprenticeship or attending the secondary school programs we recommend creating, these schools would profit less. Since these schools employ lobbyists to advocate on their behalf, these powerful players would object to reducing the illegitimate requirements from which their clients profit.

For example, documents from the Illinois Association of Cosmetology Schools oppose HB 4617—which proposes a combination of online education and hands-on training for cosmetologists instead of the current all in-person education requirement—for the express reason that it “would lead to a dramatic decrease in enrollment in cosmetology schools across Illinois.”125

The response to for-profit schools and their lobbyists is simple: If your schools provide true value, students will continue to pay to learn a trade. Culinary schools are a great example of this: plenty of people still attend culinary school despite it not being necessary to become a chef. How is it fair to force people to consume an unnecessary education when they can learn the trade themselves? How is it fair to deny poor people and minorities the opportunity to practice a profession if they lack the resources to pay for an unnecessary, expensive, and time-consuming education? It’s not fair, and it hurts the people most in need of work and opportunity.

Conclusion

Illinois’ elected officials must decide how far they want to take their commitment to expanding opportunity and equitably empowering Illinoisans. The state has taken important steps in recent years down the path to empowerment.

These reforms have created fertile soil for the next set of common-sense reforms recommended in this report. They have created momentum, too.

According to a report from the Archbridge Institute released earlier this year, social mobility in Illinois is lowest among all Midwest states and is 40th overall in America. If Illinois wants to empower more citizens, especially minorities and poor people, removing or easing occupational burdens is a simple and effective way to do it.

In 2023, 83,839 Illinois residents moved to other states. Illinois lost a net 32,826 residents when accounting for people moving into the state. That was third worst across the nation, behind only California and New York. To reverse this dire trend, Illinois needs to reorient itself as an opportunity society.

Will Illinois become a leader in opportunity and bring empowerment to more citizens? Or will it remain inequitable?

The choice may be simple, and but following through is not easy. And the only path to equity and empowerment is through removing harmful barriers to people unleashing their potential. Once they can do that, our communities and economy will be stronger, and we’ll all be better off.

Appendix A: Model Legislation

Recommended changes to current statutory language appear in bold.

Policy 1: Amends the Regulatory Sunset Act. Changes deadline for publication of sunset reviews. Adds criteria to be considered in sunset reviews.

Changes to Sec. 5. Study and report. The Governor’s Office of Management and Budget shall study annually the performance of each regulatory agency and program scheduled for termination in the second year following under this Act and report annually to the Governor the results of such study, including in the report an analysis of whether the agency or program restricts a profession, occupation, business, industry, or trade any more than is necessary to protect the public health, safety, or welfare from significant and discernible harm or damage, and recommendations with respect to those agencies and programs the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget determines should be terminated, modified, or continued by the State. The Governor shall review the report of the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget and in each even-numbered year, no later than December 1 of that year, make recommendations to the General Assembly on the termination, modification, or continuation of regulatory agencies and programs scheduled for termination in the second year following.

Changes to Sec. 6. Factors to be studied. In conducting the study required under Section 5, the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget shall consider, but is not limited to consideration of, the following factors in determining whether an agency or program should be recommended for termination, modification, or continuation:

(2) the extent to which the profession, occupation, business, industry, or trade licensed, supervised, exercised control over, issued rules regarding, or otherwise regulated by the agency or program is restricted in other US states or territories;

Policy 2: Section 1. Short title. This Act may be cited as the Professional Apprenticeship Recognition Act

Section 5. Definitions. As used in this Act:

“Apprentice” means a person who is at least sixteen years of age, except where a higher minimum age is required by law, who is employed in an apprenticeable occupation, who is a resident of the state of Illinois, and is registered in Illinois with the United States Department of Labor, Office of Apprenticeship.

“Apprenticeship program” means a program registered with the United States department of labor, office of apprenticeship, which includes terms and conditions for the qualification, recruitment, selection, employment, and training of apprentices, including the requirement for a written apprenticeship agreement.

Section 10. Apprenticeship – License.

Notwithstanding any provision of law to the contrary, for all professions and occupations regulated by the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation requiring a license to practice that profession or occupation, a person who submits as part of their application for licensure proof of completion of an apprenticeship program in the relevant profession or occupation, shall be exempt from any training or education requirements otherwise required for the initial grant of licensure. This exemption does not apply to continued training or education requirements required for current license holders to maintain or renew an existing license. An applicant licensed to practice an occupation or profession through completion of an apprenticeship as authorized under this section remains subject to any other requirements established by the agency or program regulating that occupation or profession, but those requirements may not be more onerous than those faced by non-apprentice applicants.

Policy 3: Instructs the Department overseeing approval of schools, training or educational programs for occupational licensing requirements to allow online asynchronous education wherever possible.

For all agencies and programs requiring a license to practice a profession or occupation and requiring completion of schooling, training, or some other education requirement, where the Department overseeing approval of schools, training or educational programs determines that online, and/or asynchronous schooling, training, or education can reasonably provide similar schooling, training, or education for a part or whole of an agency or program’s education or training requirement for licensure, the Department shall approve the school, training or educational program, provided fulfillment of any other requirements of the Department.

Appendix B: Legislation Passed in 2024

Illinois’ growing appetite for occupational licensing reform is demonstrated by legislation passed in the 103rd General Assembly.127

Appendix C: Legislation to Reintroduce 2025 After Not Passing in 2024

Here, we provide a shortlist of occupational licensing reform legislation from the 103rd session that failed to pass that lawmakers should reintroduce in 2025. The advantage of reintroducing previously crafted legislation is that lawmakers need not go through the process of drafting new bills.128

Endnotes

1 Morris M. Kleiner, “A License for Protection,” Regulation 29, no. 3 (Fall 2006): 17-21. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=944887.

2 Matthew Mitchell, “Policy Spotlight: Occupational Licensing and the Poor and Disadvantaged,” Mercatus Center, September 2017, https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/policy-spotlight-occupational-licensing-and-poor-and-disadvantaged.

3 Brad Hershbein, David Boddy, and Melissa Kearney, “Nearly 30 Percent of Workers in the U.S. Need a License to Perform Their Job: It is Time to Examine Occupational Licensing Practices,” Brookings, January 27, 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/nearly-30-percent-of-workers-in-the-u-s-need-a-license-to-perform-their-job-it-is-time-to-examine-occupational-licensing-practices/.

4 “Certification and Licensing Status of the Employed by Occupation.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 26, 2024. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat53.htm.

5 Tyler Boesch, Katherine Lim, and Ryan Nunn, “How Occupational Licensing Limits Access to Jobs Among Workers of Color,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, March 2022. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2022/how-occupational-licensing-limits-access-to-jobs-among-workers-of-color.

6 Noah Trudeau and Edward Timmons, “State Occupational Licensing Index 2024” (Archbridge Institute, 2024), https://www.archbridgeinstitute.org/state-occupational-licensing-index-2024/.

7 Lisa Knepper, Darwynn Deyo, Kyle Sweetland, Jason Tiezzi, and Alec Mena, License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing, 3rd ed. (Arlington, VA: Institute for Justice, 2022), 24.

8 Morris M. Kleiner, “Reforming Occupational Licensing Policies,” Hamilton Project Discussion Paper no. 2015-01 (March 2015): 9.

9 “Illinois Economy at a Glance.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, June 2024. https://www.bls.gov/eag/eag.il.htm.

10 Small Business Advocacy Council, “IACCE Zoom Chat with Speaker Chris Welch,” YouTube video, November 20, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMByESJOy9U.

11 IL Gen. Assemb. P.A. 103-708, Reg. Sess. 103rd G.A. 2023-2024 (2024), https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=5353&GAID=17&GA=103&DocTypeID=HB&LegID=153579&SessionID=112&SpecSess=.

12 IL Gen. Assemb. P.A. 103-686, Reg. Sess. 103rd G.A. 2023-2024 (2024), https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=5047&GAID=17&GA=103&DocTypeID=HB&LegID=153036&SessionID=112&SpecSess=.

13 IL Gen. Assemb. P.A. 103-687, Reg. Sess. 103rd G.A. 2023-2024 (2024), https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=5059&GAID=17&GA=103&DocTypeID=HB&LegID=153049&SessionID=112&SpecSess=.

14IL Gen. Assemb. P.A. 103-240, Reg. Sess. 103rd G.A. 2023-2024 (2023), https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=1889&GAID=17&GA=103&DocTypeID=SB&LegID=146733&SessionID=112&SpecSess=.

15IL Gen. Assemb. P.A. 103-467, Reg. Sess. 103rd G.A. 2023-2024 (2023), https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=2123&GAID=17&GA=103&DocTypeID=SB&LegID=147000&SessionID=112&SpecSess=.

16 “FACT SHEET: New Steps to Reduce Unnecessary Occupation Licenses that are Limiting Worker Mobility and Reducing Wages,” June 17, 2016, The Obama White House Archives, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/06/17/fact-sheet-new-steps-reduce-unnecessary-occupation-licenses-are-limiting.

17 Exec. Order No. 14,036, 86 FR 36987 (July 14, 2021). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/07/14/2021-15069/promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy.

18 Elizabeth Warren, “A Comprehensive Agenda to Boost America’s Small Businesses,” https://elizabethwarren.com/plans/small-businesses.

19 The Obama White House, Occupational Licensing: A Framework for Policymakers (2015).

20 “OCCUPATIONAL LICENSING: HOW A NEW GUILD MENTALITY THWARTS INNOVATION,” Progressive Policy Institute, April 2, 2012. https://www.progressivepolicy.org/pressrelease/occupational-licensing-how-a-new-guild-mentality-thwarts-innovation-2/.

21 Kleiner, “Reforming Occupational Licensing Policies.”

22 Dick M. Carpenter, Lisa Knepper, Angela C. Erickson, and John K. Ross, License to Work (Institute for Justice, 2012).

23 Farrell E. Block, Unemployment: Causes and Cures, Cato Institute Policy Analysis No. 4 (Cato Institute, 1981).

24 Tyler Boesch, Katherine Lim, and Ryan Nunn, “How Occupational Licensing Limits Access to Jobs Among Workers of Color,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, March 2022. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2022/how-occupational-licensing-limits-access-to-jobs-among-workers-of-color.

25 Ibid. See also: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, “Occupational Licensing Requirements Can Limit Employment Options for Immigrants,” https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2022/occupational-licensing-requirements-can-limit-employment-options-for-immigrants.

26 Richard B. Freeman, “The Effect of Occupational Licensure on Black Occupational Attainment” in Occupational Licensure and Regulation, 166 (Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1980).

27 Tyler Boesch, Katherine Lim, and Ryan Nunn, “How Occupational Licensing Limits Access to Jobs Among Workers of Color,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, March 2022. https://www.minneapolisfed.org/article/2022/how-occupational-licensing-limits-access-to-jobs-among-workers-of-color.

28 David E. Bernstein, “Licensing Laws: A Historical Example of the Use of Government Regulatory Power against African Americans,” San Diego Law Review 31, no. 1 (1994): 89. Available at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/sdlr/vol31/iss1/5.

29 Id., 91.

30 Tanner Corley and Marcus M. Witcher, “Barber Licensing Laws in Arkansas Hurt Consumers and Minorities,” CSORWVU, January 10, 2024, https://csorwvu.com/barber-licensing-laws-in-arkansas-hurt-consumers-and-minorities/” \h.

31 Knepper, et al., License to Work 3, 88.

32 Mindy Menjou, Michael Bednarczuk, and Amy Hunter, Beauty School Debt and Dropouts: How State Cosmetology Licensing Fails Aspiring Beauty Workers (Institute for Justice, July 2021), 12. https://ij.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Beauty-School-Debt-and-Drop-Outs-July-12-WEB.pdf.

33 Dodini, “The Spillover Effects of Labor Regulations,” 34.

34 Jason Furman and Laura Giuliano, “New Data Show that Roughly One-Quarter of U.S. Workers Hold an Occupational License,” Obama White House, June 17, 2016. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2016/06/17/new-data-show-roughly-one-quarter-us-workers-hold-occupational-license.

35 Stuart Dorsey, “The Occupational Licensing Queue,” The Journal of Human Resources 15, no. 3 (1980): 424–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/145292.

36 Samuel Dodini, “The Spillover Effects of Labor Regulations on the Structure of Earnings and Employment: Evidence from Occupational Licensing,” Journal of Public Economics 225, (September 2023): 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2023.104947.

37 Ibid., 10.

38 Stephen Slivinski, “Bootstraps Tangled in Red Tape,” Goldwater Institute, February 10, 2015. https://www.goldwaterinstitute.org/bootstraps-tangled-in-red-tape/#:~:text=The%20states%20that%20license%20more,was%20about%2011%20percent%20higher.

39 Darwynn Deyo, “Licensing Barriers for Women in the Workforce” (2022), Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation.

40 Dodini, “The Spillover Effects of Labor Regulations,” 2.

41 Morris M. Kleiner and Evan J. Soltas, “A Welfare Analysis of Occupational Licensing in U.S. States,” The Review of Economic Studies 90, no. 5 (October 2023): 2481–2516. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdad015.

42 Ben Casselman, “Licensing Laws Are Shutting Young People out of the Job Market,” FiveThirtyEight, April 22, 2016. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/licensing-laws-are-shutting-young-people-out-of-the-job-market/.

43 Nick Sibilla, “Barred from Working” (Institute for Justice, August 2020); Stephen Slivinski, “Turning Shackles into Bootstraps: Why Occupational Licensing Reform Is the Missing Piece of Criminal Justice Reform,” Center for the Study of Economic Liberty at Arizona State University Policy Report no. 2016-01 (November 7, 2016).

44 Civil Administrative Code of Illinois (20 ILCS 2105/2105-135) (Department of Professional Regulation Law).

45 America Counts Staff, “Mississippi’s Population Declined 0.2%,” Census.gov, August 25, 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/state-by-state/mississippi-population-change-between-census-decade.html; America Counts Staff, “Louisiana’s Population Was 4,657,757 in 2020,” Census.gov, August 25, 2021, https://www.census.gov/library/stories/state-by-state/louisiana-population-change-between-census-decade.html#:~:text=Louisiana’s%20population%20Was%204%2C657%2C757%20in%202020.

46 Dan King, “Braider to Take Licensing Fight to Louisiana Supreme Court After Appeals Court Rules Against Her,” Institute for Justice, June 24, 2024, https://ij.org/press-release/braider-to-take-licensing-fight-to-louisiana-supreme-court-after-appeals-court-rules-against-her/.

47 Morris M. Kleiner and Evgeny Vorotnikov, At What Co$t? State and National Estimates of the Economic Costs of Occupational Licensing (Institute for Justice, November 2018). https://ij.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Licensure_Report_WEB.pdf.

48 “Unemployment Rates for States.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, August 16, 2024. https://www.bls.gov/web/laus/laumstrk.htm.

49 “Licenses by Agency.” Illinois Department of Employment Security, June 2024. https://ides.illinois.gov/content/dam/soi/en/web/ides/labor_market_information/Licenses_by_Agency24.pdf.

50 Knepper, et al., License to Work 3, 24.

51 Morris Kleiner and Ming Xu, “Occupational Licensing and Labor Market Fluidity” (July 2020), 1. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27568.

52 Janna E. Johnson and Morris M. Kleiner, “Is Occupational Licensing a Barrier to Interstate Migration?” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12, no. 3 (2020): 347–73. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20170704.

53 Alicia Morgan Plemmons, “Does Occupational Licensing Costs Disproportionately Affect the Self-Employed?” Journal of Entrepreneurship and Public Policy 10, no. 2 (2021): 175–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEPP-08-2019-0065.

54 Michelle J. White, “Small Business Bankruptcy,” Annual Review of Financial Economics 8 (2016): 317–36.

55 David Branchflower, “Self-Employment in OECD Countries,” Labour Economics 7, no. 5 (2000): 471–505; David Blau, “A Time-Series Analysis of Self-Employment in the United States,” Journal of Political Economy 95, no. 3 (1987): 445–67; Steven F. Hipple, “Multiple Jobholding During the 2000s,” Monthly Labor Review 133, no. 7 (2010): 21–32.

56 Kleiner, “Reforming Occupational Licensing Policies,” 6.

57 Illinois General Assembly Legislative Information System, “Status of All Legislation by Sponsor – 81st General Assembly,” February 23, 1981. Springfield, IL.

58 According to emails between the Illinois Policy Institute and GOMB.

59 IL Gen. Assemb. P.A. 102-1078, Reg. Sess. 102nd G.A. 2021-2022 (2022), https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=5575&GAID=16&GA=102&DocTypeID=HB&LegID=140105&SessionID=110&SpecSess=.

60 IL Gen. Assemb. P.A. 103-708, Reg. Sess. 103rd G.A. 2023-2024 (2024), https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=5353&GAID=17&GA=103&DocTypeID=HB&LegID=153579&SessionID=112&SpecSess=.

61 IL Gen. Assemb. P.A. 103-686, Reg. Sess. 103rd G.A. 2023-2024 (2024), https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=5047&GAID=17&GA=103&DocTypeID=HB&LegID=153036&SessionID=112&SpecSess=.

62 IL Gen. Assemb. P.A. 103-687, Reg. Sess. 103rd G.A. 2023-2024 (2024), https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=5059&GAID=17&GA=103&DocTypeID=HB&LegID=153049&SessionID=112&SpecSess=.