Unions flood politicians with cash: How it buys clout in Illinois General Assembly

By Mailee Smith, Jon Josko

Government unions in Illinois have tremendous power. Most are allowed to go on strike and can bargain over virtually anything.1 It creates an uneven playing field, with unions able to demand costly provisions in their contracts and threaten to strike – denying Illinoisans needed services – to get what they want.2

Until recently, the potential monetary influence of unions3 over lawmakers and the legislative process hadn’t been adequately investigated.

Using records from the Illinois State Board of Elections, the Illinois Policy Institute performed an in-depth study of the contributions received by current members of the state’s General Assembly during 2019-2020.4

Analysis

That analysis revealed more than $15.7 million flowed directly from unions and union political action committees to the campaigns of current lawmakers during 2019-2020.

But those millions don’t tell the whole story. To better put that $15.7 million in context, the Institute’s review also found:

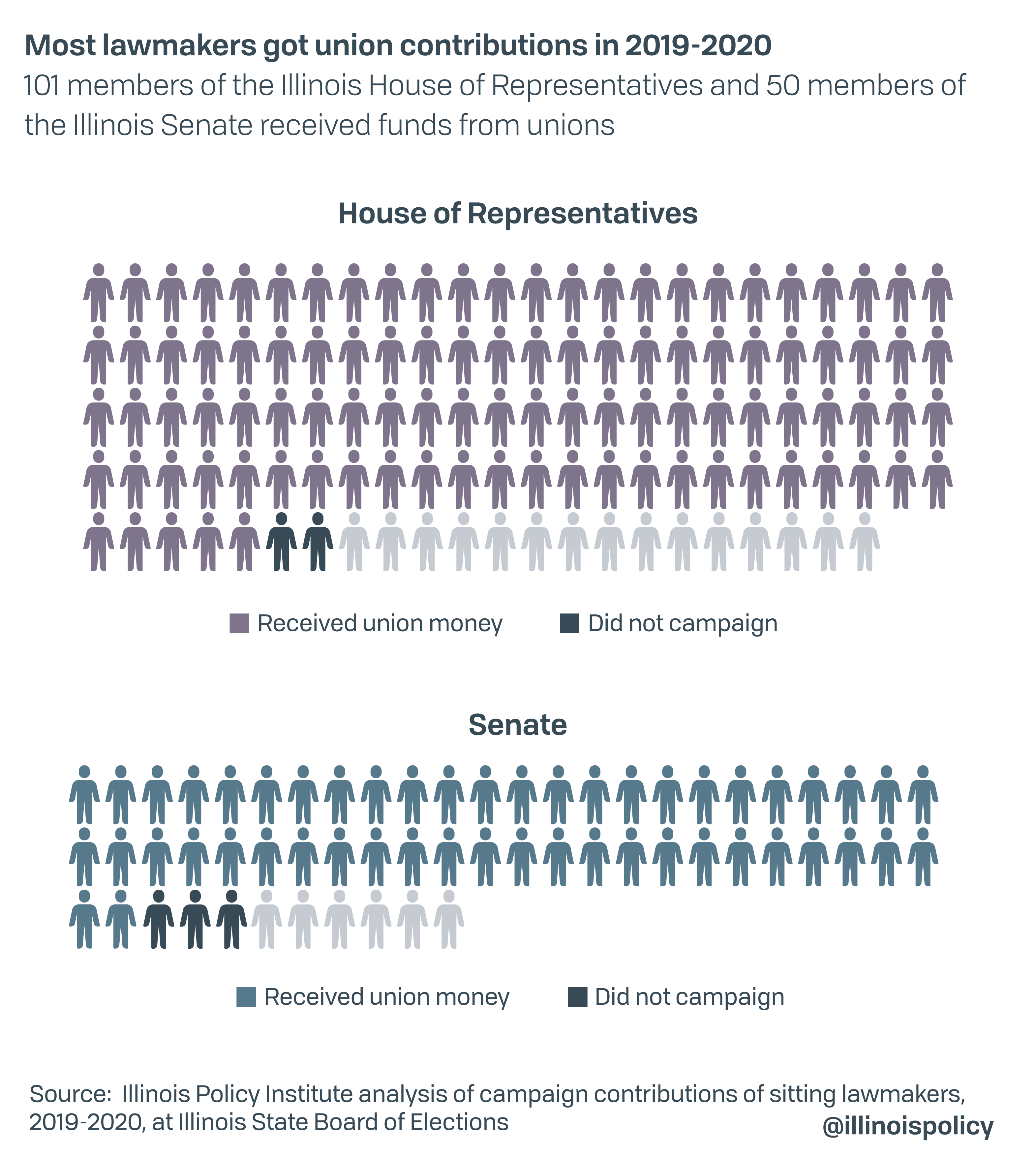

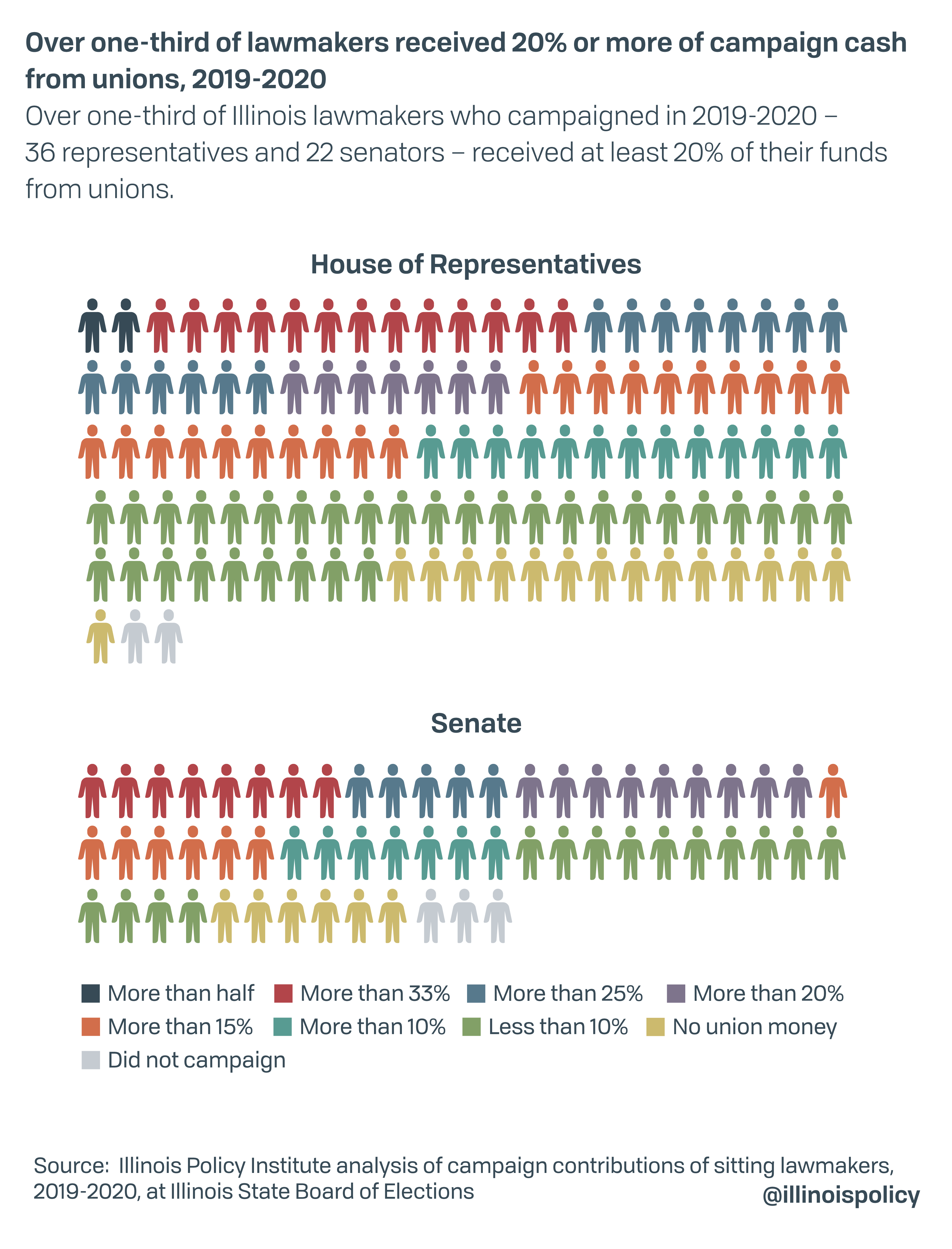

The majority of sitting lawmakers – nearly 88% – received money from unions. More than one-third of the General Assembly received more than 20% of their campaign funds from unions.

Some lawmakers received even more, with two members receiving more than half of their funding from unions and union political action committees.

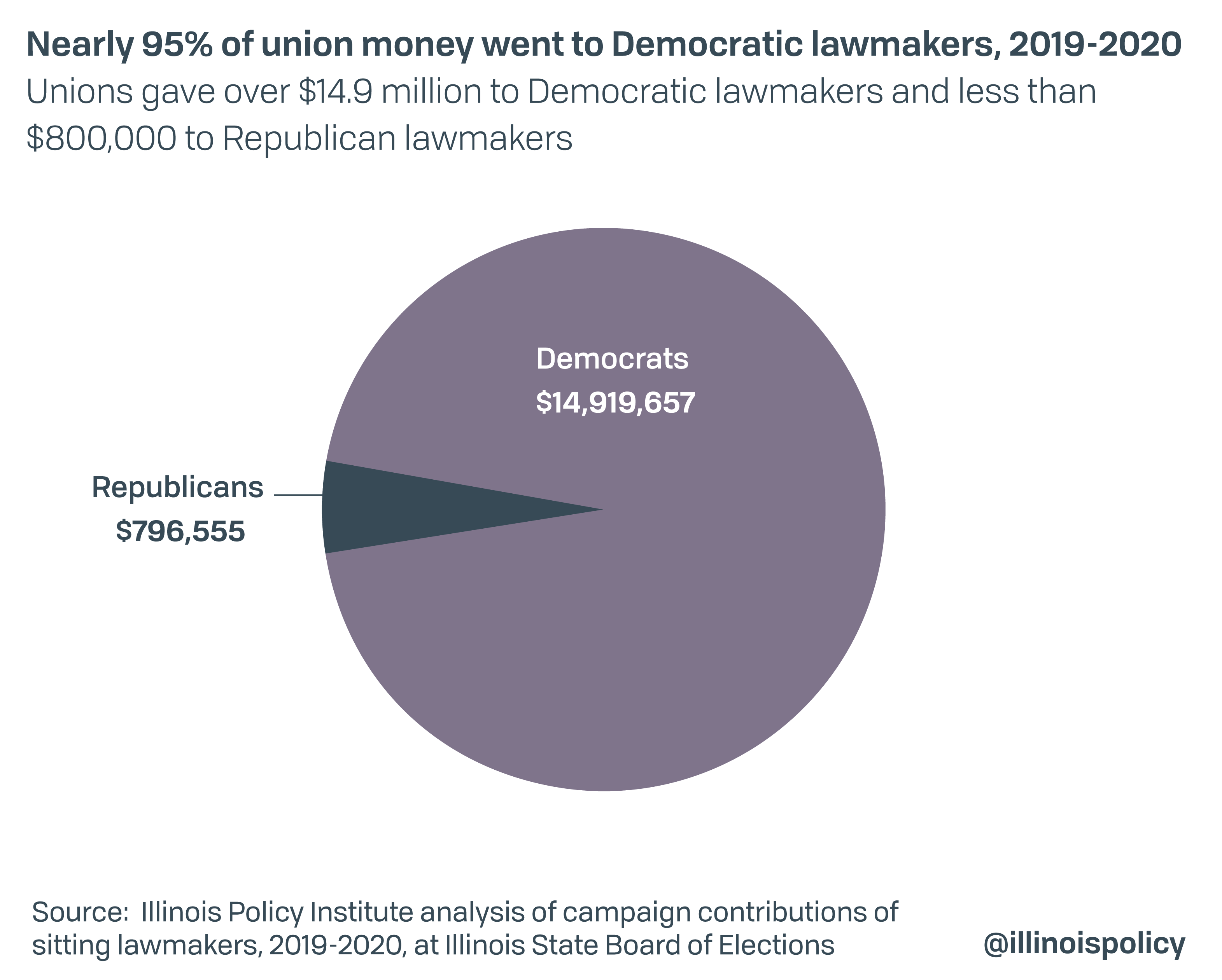

Democratic lawmakers were the main recipients, receiving nearly 95% of the direct union contributions.

Of the more than $15.7 million dollars unions contributed to state lawmakers’ political campaigns in 2019-2020, over $14.9 million (94.9%) went to Democratic members.

Recipients included 109 of 110 Democratic lawmakers who campaigned in 2019-2020.

On the Republican side, 42 of 62 who campaigned in 2019-2020 received funds from unions, but the overall union share of those lawmakers’ receipts from unions was lower than those of their Democratic counterparts.

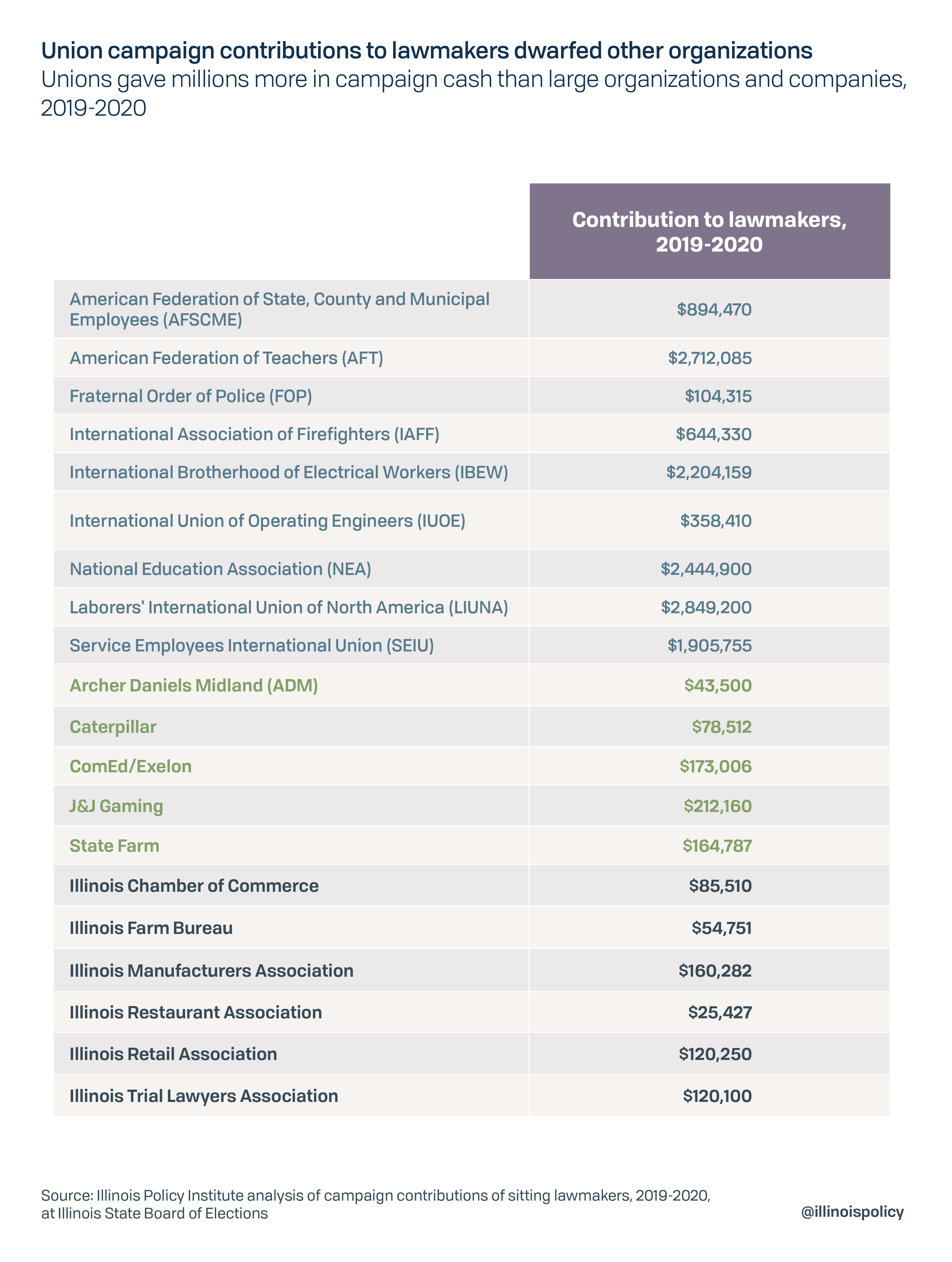

Contributions from businesses or other associations paled in comparison to union contributions.

While businesses frequently come under fire for corporate lobbying, records with the Illinois State Board of Elections show unions’ direct contributions were more substantial.

For example, ComEd and its parent company, Exelon, together directly contributed just over $173,000 to lawmakers campaigning for election in 2019-2020. That compares to $2.7 million contributed by affiliates of the American Federation of Teachers and $1.9 million given by affiliates of the Service Employees International Union.

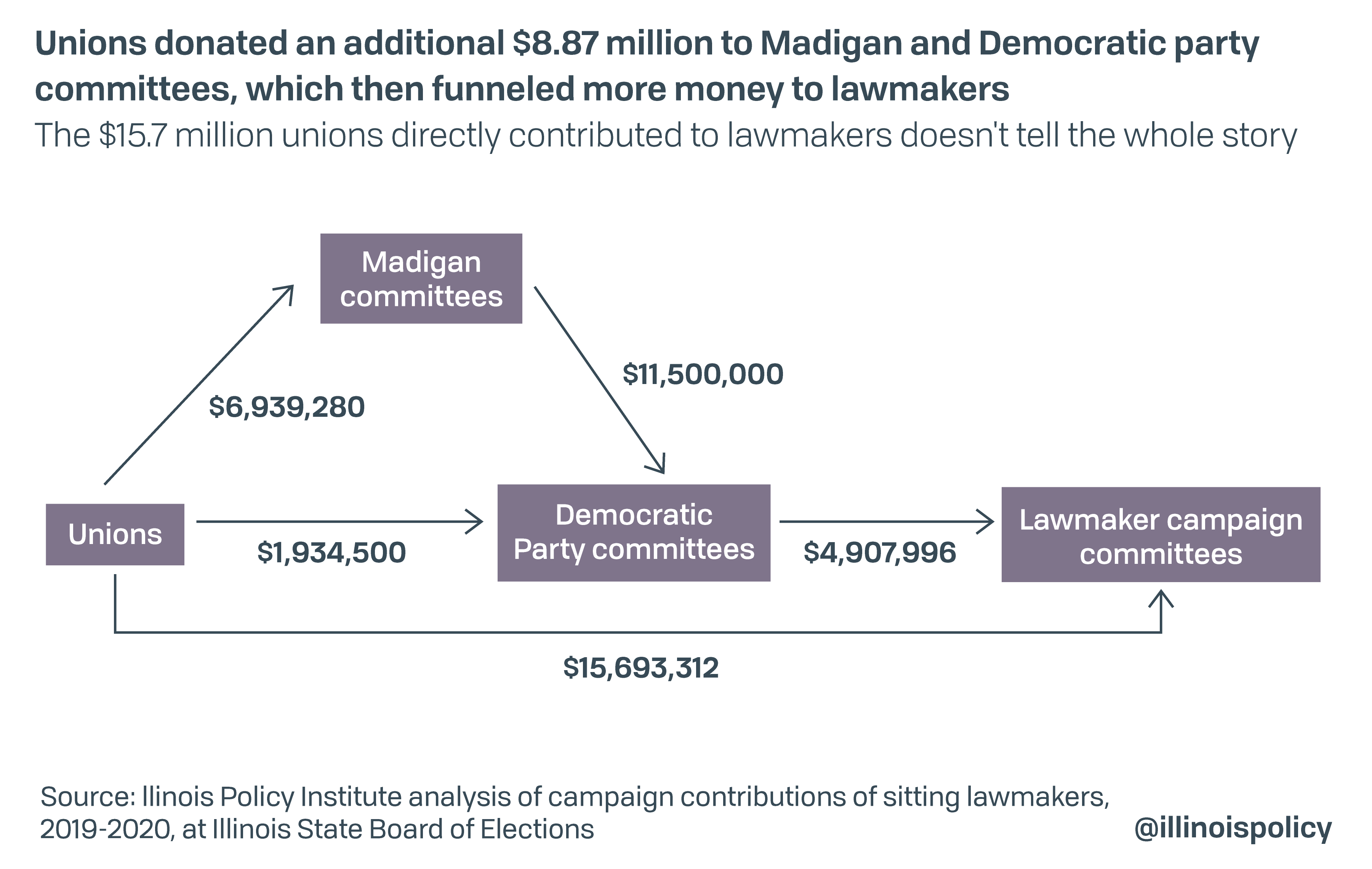

Unions also funneled money to candidates in other ways.

Besides direct contributions, unions also directed millions of dollars to Democratic Party campaign funds and former party chairman Michael J. Madigan, who re-directed money to candidate campaigns.

In other words, the $15.7 million isn’t the only money unions used to fund sitting lawmakers who campaigned in 2019-2020.

Why does this influx of union money to lawmakers matter? Because money is influential and can drive legislative decisions.5 In fact, union pressure contributed to the demise of multiple pieces of bipartisan legislation during the 2021 session.6

While unions’ monetary power over lawmakers cannot be precisely determined – in part because their funding goes through multiple channels – it does appear to be unmatched in Illinois.

Most sitting lawmakers – nearly 88% – received money from unions, totaling at least 20% of funding for more than one-third of the Illinois General Assembly

The majority of current lawmakers received funds from unions in 2019-2020, with 151 of the 172 who campaigned receiving contributions.7

Perhaps more compelling is just how large a share these union contributions were of lawmakers’ total funds, with more than one-third of lawmakers receiving 20% or more of their funding from unions. Many lawmakers received more.8

The share of lawmakers’ contributions coming from unions helps explain the unions’ hold over what happens in the Illinois General Assembly – including whether popular bipartisan bills are passed or rejected.

Democratic lawmakers received nearly 95% of direct union contributions

Unions demonstrated a clear political leaning in their campaign contributions. Not only did nearly all Democratic lawmakers who campaigned in 2019-2020 receive money from unions, but the overall amount of union contributions to Democratic lawmakers vastly outweighed that contributed to Republicans.

Of the more than $15.7 million dollars unions contributed to lawmakers’ political campaigns in 2019-2020, over $14.9 million (94.9%) went to Democrats.9

Recipients included 109 of 110 Democratic lawmakers who campaigned in 2019-2020.10

On the Republican side, 42 of 62 who campaigned received funds from unions, but those contributions were much smaller.11

Every lawmaker receiving one-third or more of his or her funding from union contributions was a Democrat.12 Union contributions amounted to less than 10% of total campaign funding for most Republicans who received union money.13

Contributions from businesses or other associations paled in comparison to union contributions

Just knowing how much sitting lawmakers received from unions fails to tell the whole story. It is necessary to compare contributions from other Illinois companies and associations to understand the context in which union contributions are made and how influential they are.

What that comparison reveals: direct contributions from other entities paled in comparison to unions’ direct contributions to lawmakers campaigning in 2019-2020.

ComEd is perhaps the most notorious company for entering the legislative and lobbying fray in Illinois. It was the ComEd “bribes-for-favors scandal” that contributed to the resignation of longtime Illinois Speaker of the House of Representatives Michael Madigan.14 After prosecutors announced a federal criminal complaint against the company in 2020, ComEd agreed to pay a $200 million fine and cooperate with the ongoing federal investigation in exchange for a three-year deferment of its prosecution.15

Yet ComEd and its parent company, Exelon, together directly contributed just over $173,000 to lawmakers campaigning for election in 2019-2020, a fraction of the $2.7 million contributed by affiliates of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) or the $1.9 million given by affiliates of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU).16

Similarly, J&J Gaming, a gaming venture that pushes “pro-industry legislation,”17 contributed just over $212,000 to campaigning lawmakers in 2019-2020.

Other Illinois-based companies also contributed surprisingly little to lawmakers’ campaigns, such as Fortune 100 companies Archer Daniels Midland at $43,500 and Caterpillar at just over $78,500.18

The same can be said of Illinois associations that lobby on behalf of employer or business interests. For example, the Illinois Manufacturers’ Association contributed just over $160,000, while the Illinois Chamber of Commerce contributed just over $83,500 to lawmakers campaigning in 2019-2020.

Businesses frequently come under fire for corporate lobbying, but records with the Illinois State Board of Elections revealing the millions of dollars unions funnel into campaign committees tell a different story.19

Unions also funneled money to candidates in other ways

While unions funneled over $15.7 million to lawmakers in 2019-2020, that doesn’t represent the full amount.

That’s because unions can contribute to candidates in multiple ways, including:

- Direct contributions to lawmakers’ campaign committees (i.e., the $15.7 million)

- Contributions to political party committees, which then pass funds to the lawmakers’ campaign committees

- Contributions to Michael Madigan’s campaign committee, which then pass funds to lawmakers’ campaign committees.

Specifically, unions contributed an additional $1.9 million to Democratic Party committees.20

Those committees then contributed over $4.9 million to lawmakers.21

Similarly, unions contributed over $6.9 million to Friends of Michael J. Madigan and his 13th Ward Democratic Organization,22 which then contributed $11.5 million to the party committees. Those, as already mentioned, then funneled money to lawmakers’ campaign committees.23

That is not to say every dollar unions passed on to Democratic committees and Madigan went on to candidate campaigns.24 But it does mean the $15.7 million isn’t the only money unions used to fund sitting lawmakers who campaigned in 2019-2020.

Conclusion

Unions’ monetary power over lawmakers cannot be precisely determined – in part because unions funnel money to candidates in multiple ways – but the union block of contributions appears to be unmatched in Illinois.

In 2021, this influence helped unions kill bipartisan legislation that otherwise carried popular support.

For example, the Classrooms First Act, or House Bill 7, sponsored by state Rep. Rita Mayfield, D-Waukegan, would have commissioned a study to review excessive school district administration costs and recommend certain districts for consolidation. Not one school would be closed, but Illinois could have saved $716 million in bureaucratic costs at the district level. That money could have been sent straight to classrooms instead of supporting multiple and duplicate high salaries for administrators who aren’t in the classrooms.

The measure appeared to have popular support, and it passed out of committee unanimously. But the Illinois Federation of Teachers and Illinois Education Association published materials opposing the bill, and HB 7 failed in a 55-42 floor vote.

Another example: the Nurse Licensure Compact. To date, 34 states have joined a national compact that recognizes the licenses for all nurses working in states that belong to the compact. Illinois had the opportunity to join the compact through Senate Bill 2068, sponsored by state Sen. Sara Feigenholtz, D-Chicago. Illinois already faced a shortage of nurses before the COVID-19 pandemic began, and SB 2068 would have allowed more nurses to come to Illinois and help alleviate the state’s long-term shortage.

The bill was unanimously passed by the Senate Licensed Activities Committee and supporters of the bill greatly outnumbered opponents. Despite bipartisan support for both the House and Senate versions of the bill, it was opposed by the Illinois AFL-CIO, the Illinois Nurses Association and the Chicago Federation of Labor, and it never received another vote.

Evidence of unions’ financial contributions to sitting lawmakers, and the relative weight of those contributions in comparison to funding from other entities, cements unions as a lobbying powerhouse in Illinois.

Not only do current labor laws favor unions over residents, but clearly unions use their wallets to ensure their power to advance their interests ahead of the interests of others.

Endnotes

1See Mailee Smith, “Rigged: How Illinois’ labor laws stack the deck against taxpayers,” Illinois Policy Institute, (Winter 2017), https://www.illinoispolicy.org/reports/rigged-how-illinois-labor-laws-stack-the-deck-against-taxpayers/.

2See, e.g., Mailee Smith, “Rigged: How Illinois’ labor laws stack the deck against taxpayers,” Illinois Policy Institute, (Winter 2017), https://www.illinoispolicy.org/reports/rigged-how-illinois-labor-laws-stack-the-deck-against-taxpayers/; Mailee Smith, “5 examples of government union power over the people, and 2 solutions to fix the problem,” Illinois Policy Institute, https://www.illinoispolicy.org/reports/5-examples-of-government-union-power-over-the-people-and-2-solutions-to-fix-the-problem/; Mailee Smith, “AFSCME: The 800-pound gorilla at the negotiating table,” Illinois Policy Institute, https://www.illinoispolicy.org/reports/afscme-the-800-pound-gorilla-at-the-negotiating-table/.

3Illinois Policy Institute utilized records filed with the Illinois State Board of Elections to analyze the contributions given by unions from Jan. 1, 2019, through Dec. 31, 2020. Because there is overlap in union membership – with some unions representing both public-sector and private-sector workers – records for all unions contributing to lawmaker campaigns during that time were analyzed.

4Of the 177 current members of the Illinois General Assembly, 172 campaigned and received contributions in 2019-2020. The other five replaced members post-election and did not campaign. State Rep. Michael Madigan resigned and was replaced by Rep. Angelica Guerrero-Cuellar, D-Chicago; Rep. Andre Thapedi resigned and was replaced by Rep. Cyril Nichols, D-Burbank; Sen. Heather Steans resigned and was replaced by Sen. Mike Simmons, D-Chicago; Sen. Bill Brady resigned and was replaced by Sen. Sally Turner, R-Lincoln; and Sen. Andy Manar resigned and was replaced by Sen. Doris Turner, D-Carlinville. The review and percentages discussed hereafter are based on the 172 members who campaigned and received funds during 2019-2020.

5The majority of current lawmakers received funds from unions in 2019-2020, with 151 of the 172 who campaigned receiving contributions.[iii]

See, e.g., Thomas Stratmann, “Can special interests buy congressional votes? Evidence from financial services legislation,” The Journal of Law and Economics (Oct. 2002), https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/340091; Brandice Canes-Wrone and Nathan Gibson, “Does money buy congressional love? Individual donors and legislative voting,” Congress & the Presidency (Feb. 5, 2019), https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07343469.2018.1518965.

6See Conclusion, infra.

7Illinois Policy Institute analysis of campaign contributions of sitting lawmakers, 2019-2020, at Illinois State Board of Elections, https://www.elections.il.gov/. Two members of the House and three members of the Senate did not campaign, so they did not raise funds in 2019-2020. See supra, n. ___. [to be filled in after finalized]

8Illinois Policy Institute analysis of campaign contributions of sitting lawmakers, 2019-2020, at Illinois State Board of Elections, https://www.elections.il.gov/.

9Illinois Policy Institute analysis of campaign contributions of sitting lawmakers, 2019-2020, at Illinois State Board of Elections, https://www.elections.il.gov/.

10Illinois Policy Institute analysis of campaign contributions of sitting lawmakers, 2019-2020, at Illinois State Board of Elections, https://www.elections.il.gov/.

11Illinois Policy Institute analysis of campaign contributions of sitting lawmakers, 2019-2020, at Illinois State Board of Elections, https://www.elections.il.gov/.

12Illinois Policy Institute analysis of campaign contributions of sitting lawmakers, 2019-2020, at Illinois State Board of Elections, https://www.elections.il.gov/. See supra Part I for breakdowns on overall union giving to members.

13Union contributions constituted less than 10% of campaign funding for 33 of the 42 Republicans who received union contributions in 2019-2020. Illinois Policy Institute analysis of campaign contributions of sitting lawmakers, 2019-2020, at Illinois State Board of Elections, https://www.elections.il.gov/

14Ray Long, “Illinois Commerce Commission starts ComEd probe, wants to know if ratepayers picked up improper costs,” Chicago Tribune, Aug. 12, 2021, https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/breaking/ct-comed-madigan-icc-20210813-3teafpvphnf3podvv264oeweqa-story.html.

15Dan Hinkel, Rick Pearson, Alice Yin, Megan Crepeau and Annie Sweeney, “Federal investigation draws closer to Madigan as ComEd will pay $200 million fine in alleged bribery scheme; Pritzker says speaker ‘must resign’ if allegations true,” Chicago Tribune, July 18, 2020, https://www.chicagotribune.com/politics/ct-comed-madigan-investigation-fine-20200717-y6w2givqzrcyvafyjny7fjw434-story.html.

16The contributions calculated for ComEd include those of Exelon. Arguably, the contributions by ComEd/Exelon during this time period may have decreased in light of the extreme scrutiny brought about by the federal investigation. Indeed, in 2017 and 2018, ComEd/Exelon contributed $728,340 to current lawmakers. But that was still much lower than what AFT and SEIU contributed during that time period, which was $3,696,324 and $2,266,654, respectively. Illinois Policy Institute analysis of campaign contributions of sitting lawmakers, 2017-2020, at Illinois State Board of Elections, https://www.elections.il.gov/.

17J&J Ventures, “Gaming Legislation Update!,” May 5, 2021, https://www.jjventures.com/2021/05/05/gaming-legislation-update/;

18Illinois Policy Institute analysis of campaign contributions of sitting lawmakers, 2019-2020, at Illinois State Board of Elections, https://www.elections.il.gov/. See also “Fortune 500,” Fortune, 2021, https://fortune.com/fortune500/2021/search/.

19What’s more, individual unions tend to use their influence in a block, banding together to fight for or against legislation. See, e.g., HB 3474, Witness Slips, https://ilga.gov/legislation/Witnessslip.asp?LegDocId=166013&DocNum=3474&DocTypeID=HB&LegID=132467&GAID=16&SessionID=110&GA=102&SpecSess=&Session=&WSType=PROP(listing nine witness slips filed by five major Illinois unions – AFSCME Council 31, IL AFL-CIO, IEA, IFT and Local 881 United Food and Commercial Workers – supporting legislation amending the portion of the pension code related to the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund to prohibit a person who meets the criteria to be an executive trustee from serving as an employee trustee on the Board). Businesses and other associations don’t tend to work together in the same way, but each act according to their own interests, making that union block influence that much more powerful. See, e.g., SB 690, Witness Slips on House Amendment 2, https://ilga.gov/legislation/Witnessslip.asp?LegDocId=154634&DocNum=0690&DocTypeID=SB&LegID=116627&GAID=15&SessionID=108&GA=101&SpecSess=&Session=&WSType=PROP(listing positions of multiple unions, including IBEW, IEA and Ironworkers Local 444, but relatively few businesses on gaming expansion legislation).

20Illinois Policy Institute analysis of campaign contributions of sitting lawmakers, 2019-2020, at Illinois State Board of Elections, https://www.elections.il.gov/. Specifically, this money was contributed to the Democratic Party of Illinois and the Democratic Majority.

21Illinois Policy Institute analysis of campaign contributions of sitting lawmakers, 2019-2020, at Illinois State Board of Elections, https://www.elections.il.gov/.

22Both the Friends of Michael J. Madigan and the 13th Ward Democratic Organization were committees controlled by Madigan. See Illinois Sunshine, Friends of Michael J. Madigan, https://illinoissunshine.org/committees/friends-of-michael-j-madigan-665/ (listing Michael J. Madigan as chair); Illinois Sunshine, 13th Ward Democratic Org, https://illinoissunshine.org/committees/10/ (listing Michael J. Madigan as chair).

23Illinois Policy Institute analysis of campaign contributions of sitting lawmakers, 2019-2020, at Illinois State Board of Elections, https://www.elections.il.gov/.

24Not all money unions contributed to political parties or Madigan went to sitting lawmakers; some went to candidates for other offices or other causes. But money is fungible, and the use of pass-through campaign committees demonstrates that unions fund political candidates in multiple ways.