Unfair big government contracts hurt Illinois’ economy, cut job creation

By Orphe Divounguy, Mailee Smith, Bryce Hill

Illinois’ public sector employees are some of the highest paid in the nation and earn wages up to 60% higher than their private sector counterparts.

Some have justified this wage gap by pointing to differences in education and work experience. But a new Illinois Policy Institute analysis accounts for those factors and others, finding no observable reason for the large difference in wages. In addition, Illinois’ public-private pay gap is wider than those in any neighboring state or than the national average.

These public employee wage premiums not only hurt the economy through the burden of higher taxes, but also can harm private-sector workers by creating higher unemployment risk.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker recently agreed to a new contract for the state’s largest government worker union, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Council 31, which is expected to cost taxpayers an additional $3.6 billion. Included in the contract is a one-time payout of up to $2,500 per worker and annual raises whose compounded value will be a nearly 12% pay raise for the average worker, along with increased family leave. While the contract is expected to cost taxpayers billions, the true economic cost will be hidden, and much higher.

State lawmakers should pursue reforms to narrow the wage gap between public workers and their peers in the private sector.

Illinois should repeal the state law that enshrines the “right to strike” for public sector unions and ban public sector strikes, as do surrounding states. Like most neighboring states, Illinois could also limit the subjects of collective bargaining, as negotiations of every single detail of employer-employee relations often prolong contract negotiations and lead to greater taxpayer costs. Also, like most neighboring states, Illinois could limit contract duration to ensure that current contracts accurately reflect the state of the economy and what taxpayers can afford.

Without reforms that level the playing field between the public and private sectors, the cost of Illinois’ public sector workers will continue to damage the state’s labor market, economy and taxpayers.

Introduction

After four years of stalemate under former Gov. Bruce Rauner, the state’s largest government worker union, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Council 31, quickly reached an agreement after Pritzker’s inauguration. Among the new concessions from the state is a one-time payout of $2,500 per employee that has the potential to boost pensions. It was awarded on a pro-rated basis for those employees who started after Rauner halted automatic annual raises, known as step increases. The new contract gives annual pay increases whose compounded effect will be a nearly 12% raise for the average worker, plus they get increased paid family leave. In exchange for these increased benefits, employees were asked to pay a slightly higher share of their health care costs, although they still pay far less than their private sector counterparts.

The new contract is expected to cost taxpayers an additional $3.6 billion during the next four years. However, the effects of the new contract, and public employment in general, extend far beyond the economic impact of higher taxation.

Private vs. public sector in Illinois

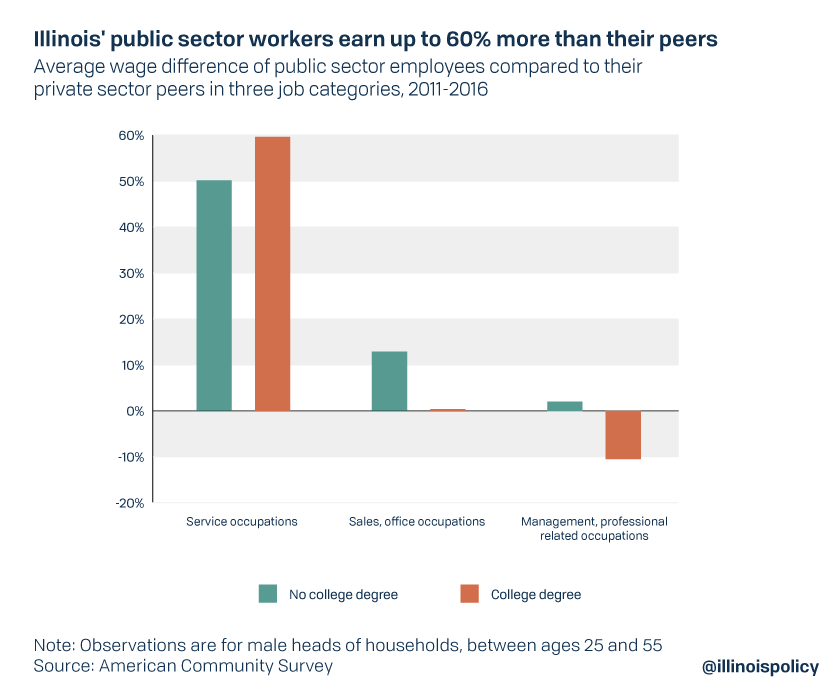

Analysis of the most recent government data reveals Illinois’ public sector wages are higher than private sector wages for nearly all occupations in the sample studied, even after controlling for worker characteristics such as professional experience and education. The exception is highly skilled workers in management, professional and related jobs. The gap is the highest for workers in service occupations. The analysis compares only employed, male heads of households from the ages of 25-55 in order to remove wage disparities resulting from gender, school enrollment or semi-retirement.

In Illinois, nearly all public sector workers earn higher wages than similar private sector counterparts. For this analysis the wage premium is defined as the hourly pay gap that cannot be explained by the observed characteristics of workers in our sample (see Appendix A).

For those in service occupations, such as health care, food service and maintenance workers, public sector workers with college degrees earn 60% more than their private sector counterparts. Those without a college degree earn 50% more than their peers.

Public sector workers in sales and office occupations, such as secretaries and data entry operators, also earn higher wages than similar workers in the private sector. Those with a college degree receive virtually no benefit of a public wage premium – their wages are 0.4% higher – meaning their salaries are in-line with the private sector. For those without a college degree, the public sector yields a 13% wage premium over those in the private sector.

Public sector employees with a college degree in the management, professional and related occupations, such as accountants, compliance officers and computer scientists, actually face a wage penalty of 10.5%. When they don’t have a college degree, that category of public workers earns 2.1% more than their private sector peers without degrees.

These results suggest the higher pay of most public sector workers relative to private sector workers in Illinois cannot be justified. Higher public wages distort the state’s labor market and harm the state’s economy.

Illinois’ neighbors

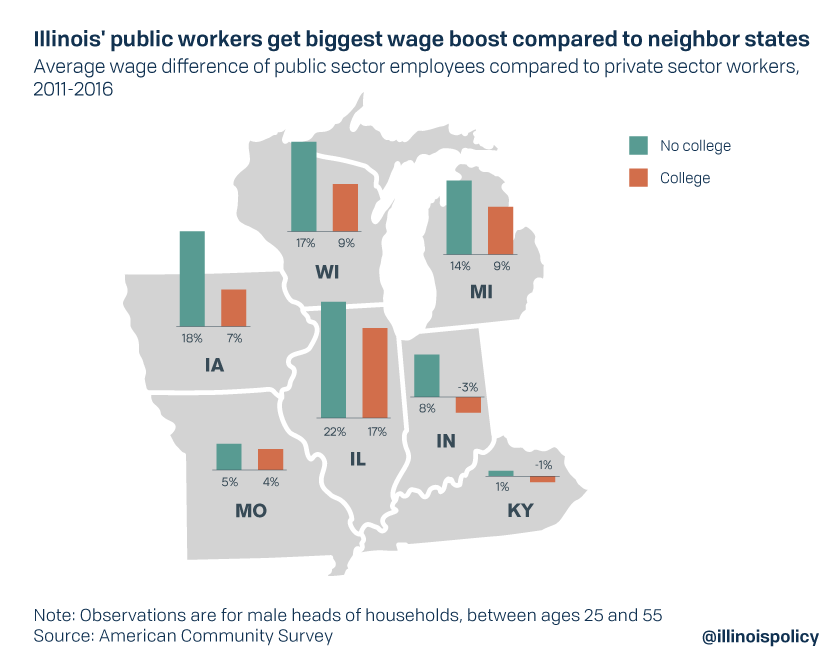

Public sector wages are higher than private sector wages in Illinois, but Illinois also offers the largest public sector wage premium when compared with neighboring states.

One of the main cost drivers in Illinois is its unfair collective bargaining laws. Those laws let Illinois public sector unions obtain higher salaries and bigger benefits at taxpayer expense.

Natural checks and balances on union demands exist in the private sector. Unions cannot demand more than a private company earns, or the company will go out of business and union workers will lose their jobs.

This is not the case in the public sector. There are no natural limits on public sector union demands for more money or more benefits. The union can demand more because the state has the ability to pass on all costs to taxpayers, who have no choice but to pay.

While no two states regulate government employer-employee relations in the exact same way, a close evaluation of the laws in each of Illinois’ neighboring states – Iowa, Wisconsin, Michigan, Indiana, Missouri and Kentucky – reveals a number of trends in the region. Each of Illinois’ neighbors has tried to rein in government costs through collective bargaining provisions. But not Illinois, making it an outlier in the region.

First, while every surrounding state prohibits strikes for most or all government workers, Illinois has gone the opposite direction, enshrining a “right to strike” in state law. A government worker strike is different than a strike in the private sector. When government workers threaten to strike, they are threatening to shut down important government functions and deprive residents of necessary services, often without alternatives. The power to strike gives Illinois public sector unions the upper hand in negotiations, and that drives up costs.

Second, there are virtually no limits on the subject matters open to negotiation in Illinois. Specifically, state law provides that negotiations between a government unit and a public sector union include “wages, hours and other conditions of employment.” The negotiation over every single detail in employer-employee relations – even details such as the minute at which school starts – ends up costing taxpayers more money. On the other hand, four of Illinois’ neighbors – Wisconsin, Iowa, Indiana and Michigan – limit in varying ways the subjects that can be negotiated by public sector unions.

Finally, there is no limit on the length of most government worker contracts in Illinois. No limits exist on contract length at the local government and school district level, while state workers’ contracts cannot exceed June 30 of the year executive branch officers begin their tenure (i.e., tied to the governor’s term). These lengthy collective bargaining agreements can leave taxpayers on the hook for expensive contract provisions many years into the future – even if the state or local economy can no longer support the provisions. Yet four of Illinois’ neighbors – Wisconsin, Iowa, Indiana and Michigan – restrict the length of some or all collective bargaining agreements.

It’s an uneven playing field, with public sector unions holding all of the power.

Why it matters

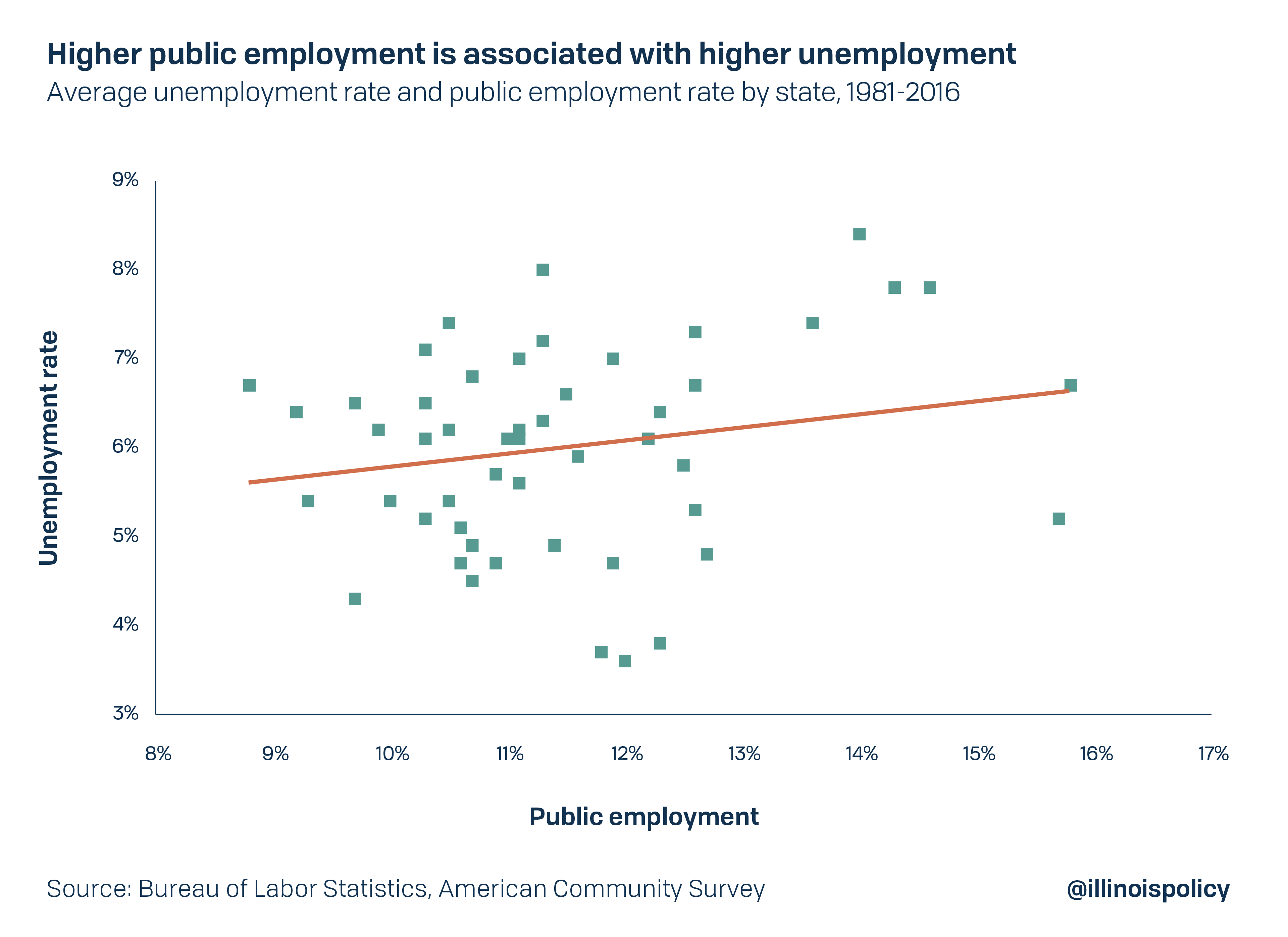

While politicians in Springfield often applaud when new agreements on contracts are reached, or when their latest public programs will be hiring new workers, they often ignore the very real impact that public employment has on the economy. Economic research has revealed that higher public sector employment can crowd out the private sector, resulting in higher unemployment, particularly in cases where higher public sector wages do not reflect productivity differences.

Growth in public sector payrolls and wages requires greater burdens of taxation that reduce private sector job creation. It can also alter the bargaining power of workers in the private sector, leading to higher labor costs that result in less hiring and longer periods of unemployment. The costs of increasing public employment often are the loss of private sector jobs that are greater or equal to the public jobs created. That means the public sector is capable of fully crowding out private employment and can increase unemployment.

Researchers have found that a 1 percent increase in public wages is associated with a 0.3% increase in private sector wages. This increase leads to wage pressure and can decrease private employment (Holmlund and Linden, 1993, Edin and Holmlund, 1997). The cost of public jobs generally implies either an increase in taxes, or reduced funding for public investments. Increased taxes reduce the after-tax profitability of firms because the higher tax bills are coupled with higher labor costs. Reduced public investment hurts the economy because resources are diverted from infrastructure projects and other public improvements that make economies more productive. In both cases, the financing implications can be distortionary and hurt aggregate output, thereby cutting private sector labor demand.

AFSCME workers are scheduled to receive a nearly 12% raise during the next few years while Illinois currently has an unemployment rate of 4.4% that leaves 285,000 Illinoisans actively looking for work.

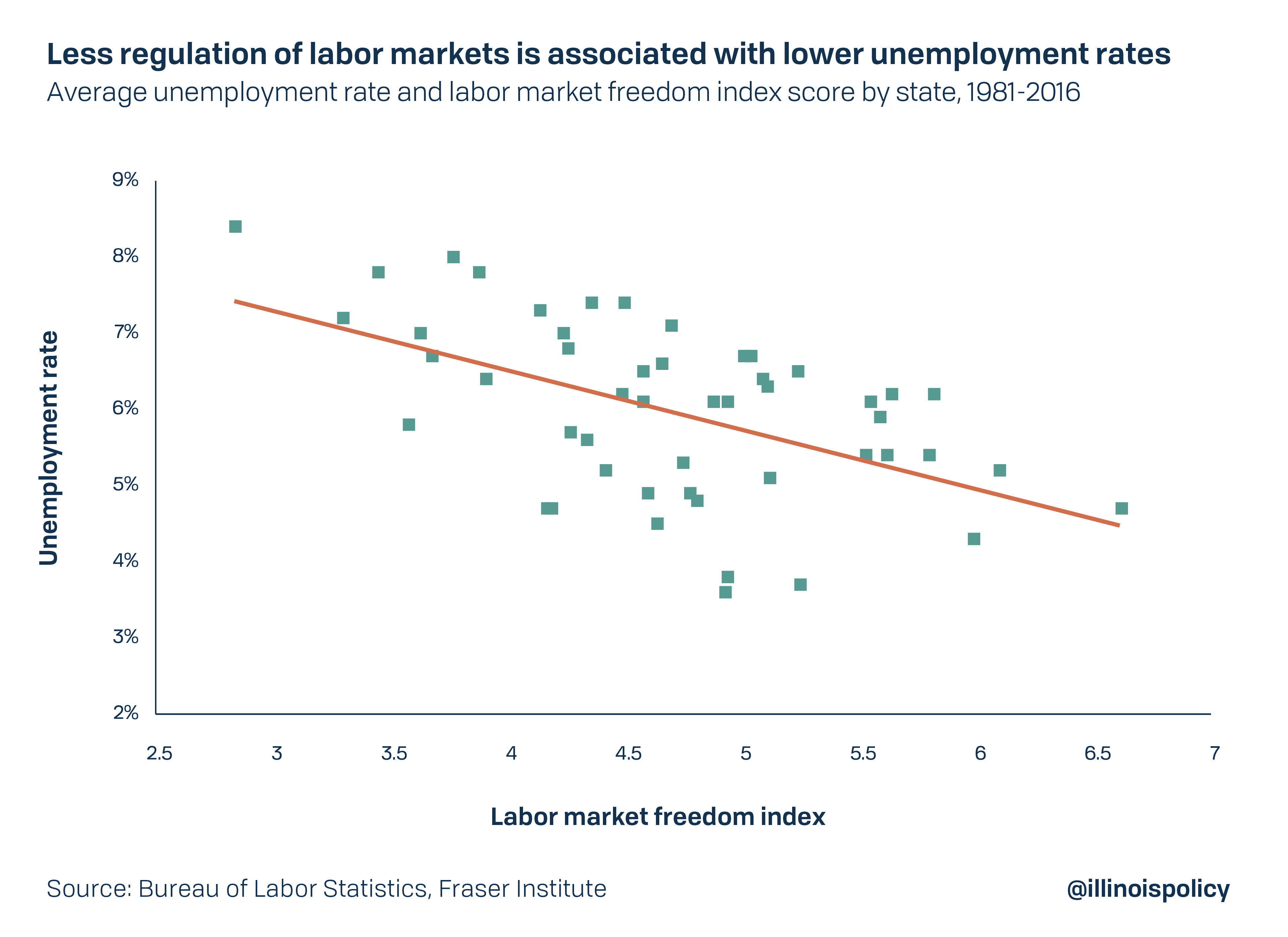

Additionally, using data from all 50 states between 1981 and 2016, research reveals that a 1 percentage point increase in the public employment rate is associated with a 0.2 percentage point rise in unemployment. On the other hand, a 1-point increase in the Fraser Institute’s labor market freedom index is associated with a 0.6 percentage point drop in the unemployment rate.

The labor market freedom index considers the amount of government regulation and the ease with which employers and employees can operate in the labor market. It includes measures for government employment, union density and minimum wage laws. Using this index provides a more comprehensive measure of the size of the public sector as well as the full influence it yields on the labor market.

If public hiring did not crowd out private sector hiring, then an increase in public hiring would be associated with a decrease in the unemployment rate. However, data from all states from 1981-2016 reveal higher public sector employment and less labor market freedom are associated with higher unemployment rates (see Appendix B).

Data from all 50 states clearly reveals the positive correlation between public employment and the unemployment rate, and a negative correlation between unemployment and labor market freedom.

These findings are consistent with the bulk of the peer-reviewed academic literature on this topic. Most recently, in a paper published by the Journal of Economics and Finance, Cebula (2019) concludes that the unemployment rate is a decreasing function of labor market freedom and that policymakers should: (a) not elevate the state’s minimum wage too aggressively; (b) limit the extent of government employment; and (c) favor enacting right-to-work laws.

Conclusion

State workers, many of whom just received a massive raise, were already the second-highest-paid in the nation. The recent agreement between Pritzker and AFSCME Council 31 is further proof that Illinois’ public sector is thriving. Unfortunately, it does so at the expense of the private sector, causing greater unemployment and hindering the state’s anemic labor market.

In order to provide more opportunity to the 285,000 Illinoisans actively searching for work, Illinois should pursue reforms that eliminate exorbitant burdens that the public sector places on the private sector.

First, Illinois should follow the lead of all the neighboring states by prohibiting strikes by most government workers. This would ensure those relying on government services, such as students and families, will not be abandoned. Illinois should also limit the subjects of collective bargaining, as do most neighboring states. Narrowing the scope of collective bargaining could streamline the negotiating process and lead to quicker contract ratifications. Additionally, the state should impose limits on the duration of public employee contracts. Limiting the duration of contracts would ensure that contracts are more reflective of current economic conditions. If a recession comes or if governments have less funds than expected due to lower economic growth, contracts should reflect taxpayers’ ability to pay for them.

More Illinoisans can continue to expect higher unemployment rates and longer durations of unemployment so long as Illinois’ labor laws continue to prioritize government workers over everyone else. While the new AFSCME contract is expected to cost taxpayers $3.6 billion, the true economic cost is much greater.

Correction: A previous version of this report contained references to restricting the wage gap analysis to white male heads of household between ages 25 and 55, while in fact the analysis includes all male heads of household between ages 25 and 55. The report has been updated to reflect the correct description of the analysis.