Pensions are a form of deferred compensation widely used in the public sector to fund retirement benefits for government workers. Due to a combination of factors including overpromising, underfunding as a result of overpromising, and structural failings, pensions are currently causing a fiscal crisis in Illinois.

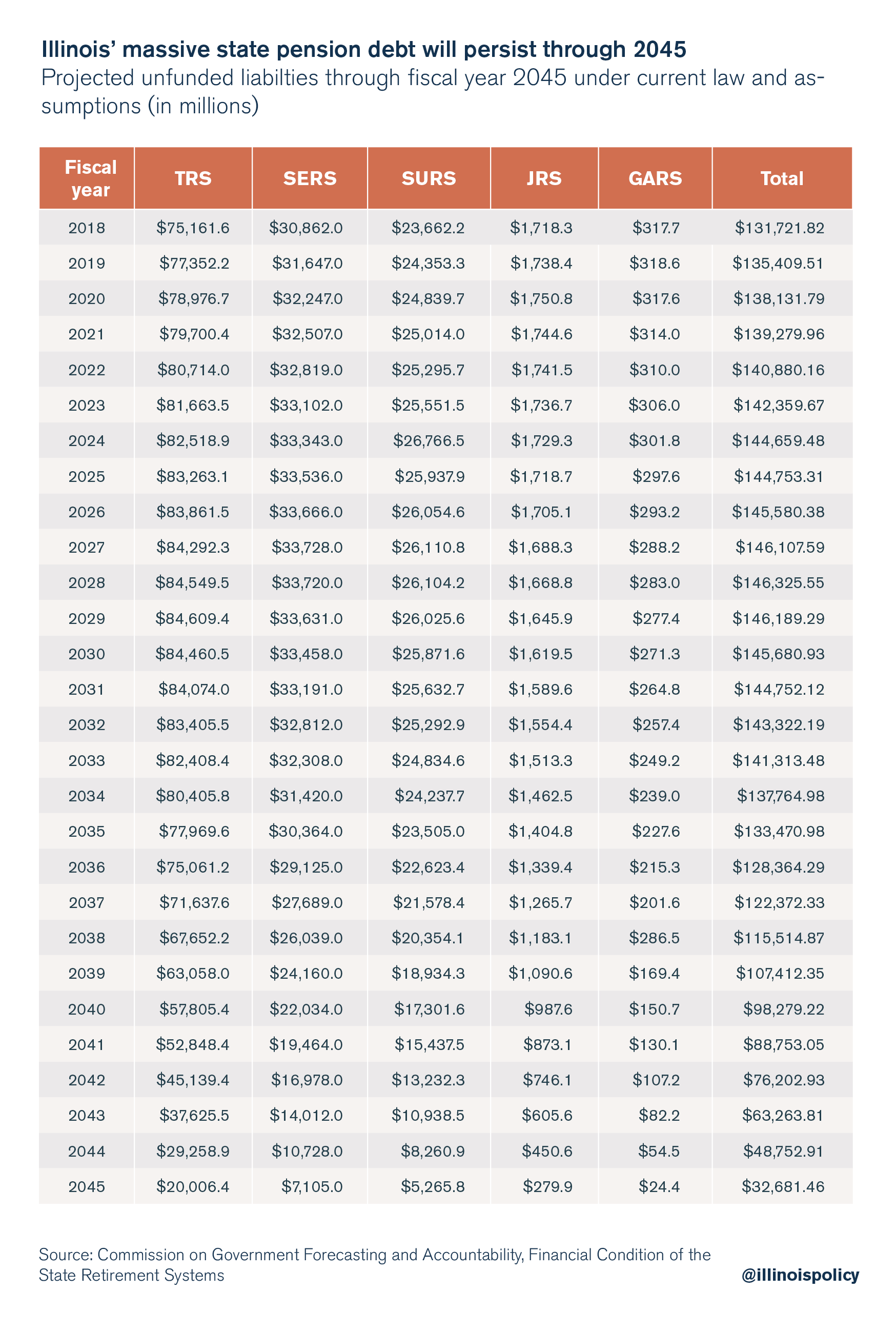

Illinois’ public pension crisis is among the worst in the nation. The state’s $130 billion unfunded pension liability – the gap between what the state has on hand and how much has been promised going forward – is a leading cause of Illinois’ worst-in-the-nation credit rating. Pension-related payments currently account for over 25 percent of the state’s annual general revenue expenditures. The share of the budget consumed by pensions will grow going forward, threatening to crowd out core services such as public safety and social welfare. Illinoisans are already experiencing this crowding-out effect at the state and local levels.

In what could be the first in a series of dominos, the city of Harvey, Illinois, demonstrated this tension between current services and retirement benefits for past employees when financial trouble related to pension payments caused mass layoffs of police and firefighters in spring 2018.

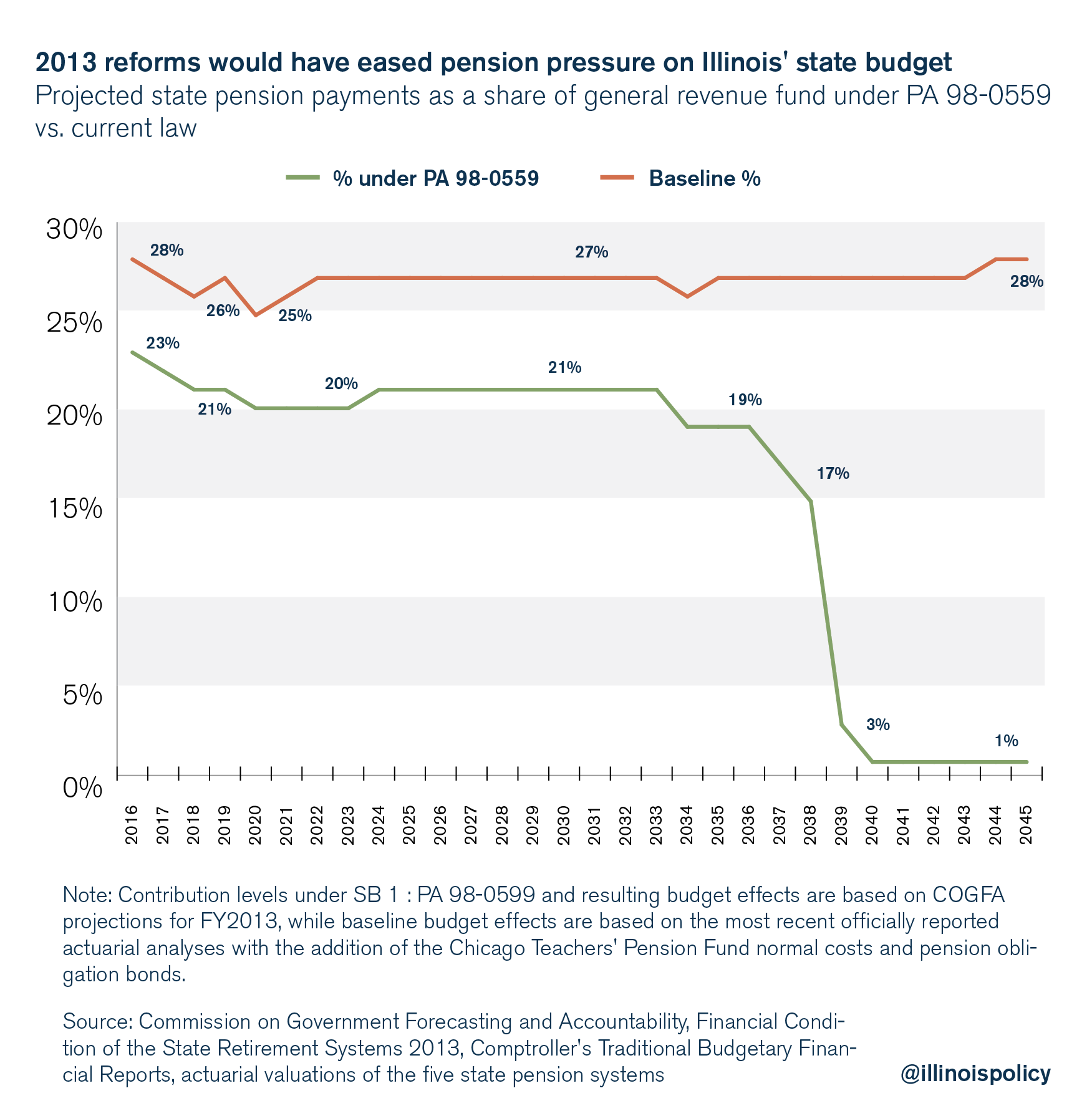

An effort to address these problems by reforming future pension growth took the form of Public Act 98-0599, which was signed into law by former Gov. Pat Quinn in 2013. But the Illinois Supreme Court blocked this measure in 2015. The pension reforms contained in PA 98-0599, while not a complete solution to Illinois’ pension problem, nonetheless provide a road map for addressing the state’s massive unfunded pension liability and could have started Illinois on a path to better finances had they been allowed to take effect.

The 2013 reforms would have protected already-earned pension benefits while reforming the future accruals, or rate of growth, in those benefits going forward. In that concept lies the path toward solving Illinois’ biggest fiscal problem.

However, due to the Illinois Supreme Court’s extraordinarily restrictive interpretation of the Illinois Constitution’s pension protection clause, enacting commonsense pension reforms will require a constitutional amendment. The only other option is massive tax hikes that would cripple the state’s economy, and fail to provide a permanent solution to the problems inherent in defined-benefit pensions.

To achieve balanced budgets and a strong credit rating – without gutting core services or crushing the state’s economy with more tax hikes – Illinois must amend the pension protection clause to make clear that while already-earned benefits are protected, future increases in those benefits are subject to change to bring them in line with what taxpayers can afford.

To eliminate the liability, lawmakers should follow the 2013 road map – with reforms focusing on the following:

- Increasing the retirement age for younger workers

- Capping maximum pensionable salaries

- Replacing permanent compounding benefit increases with true cost-of-living adjustments, or COLAs

- Implementing COLA holidays to allow inflation to catch up to past benefit increases

- Further, to ensure government worker retirements are predictable and sustainable going forward, all newly hired employees should be enrolled in 401(k)-style retirement plans, similar to what’s available to State Universities Retirement System employees, except mandatory.

Reforming future benefit growth via a constitutional amendment is the only way to ensure the retirement security of government workers, protect taxpayer budgets and fulfill the needs of Illinoisans reliant on core services.

Introduction

Government worker retirement security is primarily provided in the United States by defined-benefit pension systems. In the private sector, on the other hand, nearly 85 percent of employees are enrolled in defined-contribution systems, also called personal retirement accounts or 401(k)-style systems.1

Under defined-benefit systems, post-retirement compensation is set according to a formula that takes into account an employee’s years of service and average salary near the end of his or her career, but not the amount of money available to fund the benefits under the formula. Defined-contribution plans, in contrast, are personal accounts that an employee and employer can pay into to set aside money for retirement. Personal retirement plans grow through employee and employer contributions and investments alone, without legal guarantees about how much will be available or what the growth in retirement benefits will be. This makes the cost of personal retirement accounts significantly easier to predict, meaning they are much less likely to throw state finances into disorder.

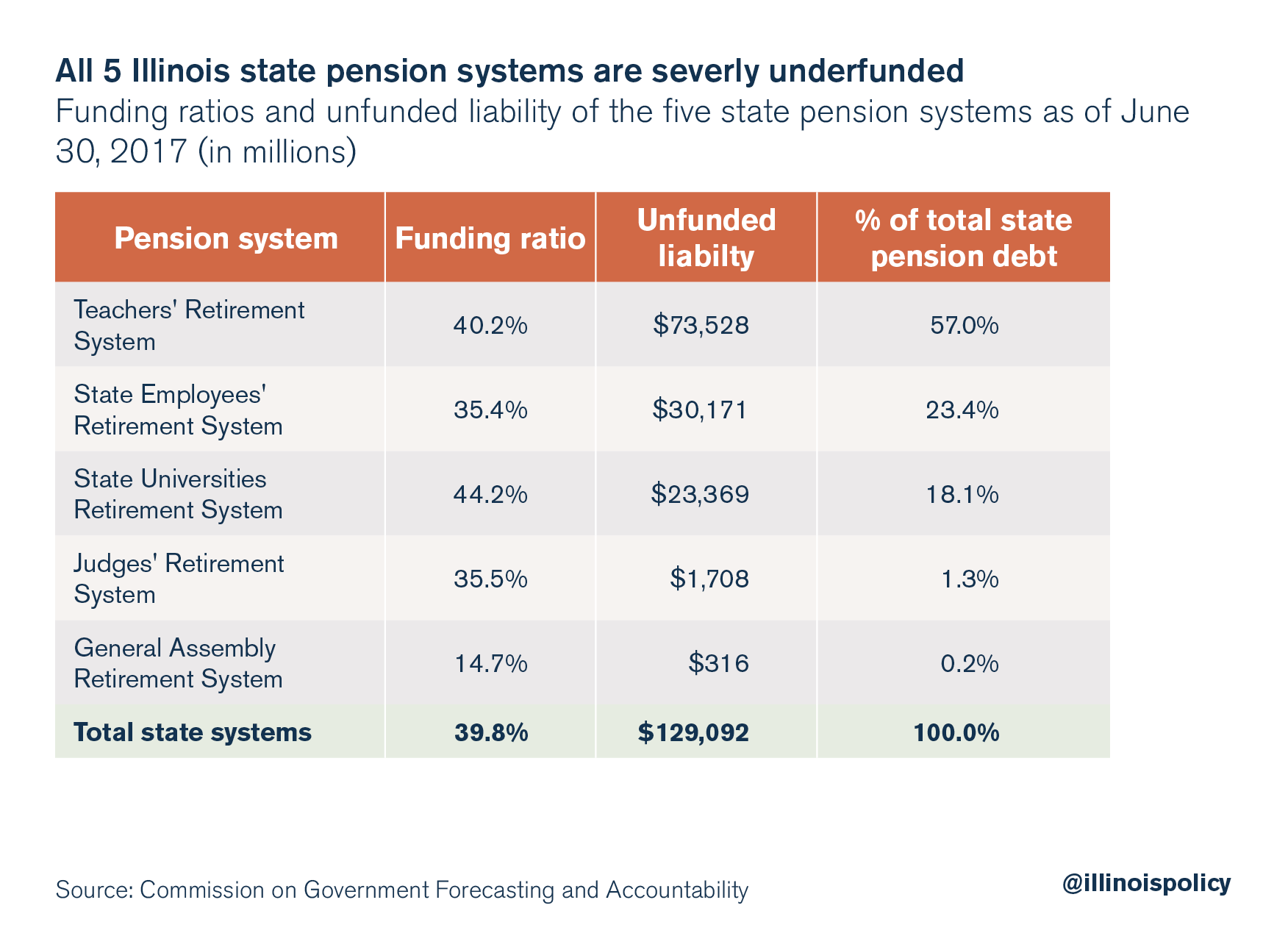

Illinois has five state pension systems and 662 local pension systems.2 The five state systems are:

- The Teachers’ Retirement System, or TRS, for pre-K through 12th-grade school employees

- The State Universities Retirement System, or SURS, for higher education employees

- The State Employees’ Retirement System, or SERS, for most agency employees

- The Judges’ Retirement System, or JRS, for judges

- And the General Assembly Retirement System, or GARS, which manages pensions for state lawmakers and statewide elected officials

Local pension systems include a fund for suburban and downstate municipal workers, three pension funds in Cook County, seven in the city of Chicago, 355 suburban and downstate police funds, and 296 downstate and suburban firefighter funds.3

Over time, taxpayer contributions to these funds have grown dramatically while government worker contributions have remained virtually flat.4 In fact, most workers contribute only about 4 to 8 percent of what they receive in retirement benefits – 8 to 16 percent including investment returns – and half will receive pensions worth over $1 million during the course of their retirement.5

Combining state and local payments, Illinois spends more than any other state on pensions as a percentage of total government spending, and nearly double the national average.6 A long history of doling out overly generous benefits – while failing to make the budget-busting contributions that would have been mathematically required to fund those benefits – has landed Illinois in dire fiscal straits.

In addition to low required worker contributions, a key driver of Illinois’ overly generous benefits is cost-of-living adjustments, or COLAs. Starting in 1990, state law guaranteed most retirees 3 percent compounding increases to their benefits after retirement, regardless of the level of inflation present in the economy.7 These increases are more appropriately called permanent benefit increases, as they were in Arizona before being replaced with genuine COLAs tied to the rate of inflation.8 In Illinois, these guaranteed permanent benefit increases can double a retiree’s pension over the course of an average retirement.9

Relatively young retirement ages are another aspect of Illinois’ pensions that make the system unaffordable for taxpayers. Many government employees have been able to start receiving pension benefits at a much younger age than workers in the private sector. While full Social Security benefits cannot be collected until age 67, about 60 percent of recent Tier 1 retirees started collecting retirement benefits in their 50s.10

In sum, public sector workers in Illinois have been able to receive benefits earlier, pay less for those benefits, and see benefits grow much faster than the benefits of private sector workers funding their plans.

The excessive cost of pension benefits in Illinois has led to their underfunding.

In the mid-1990s, former Gov. Jim Edgar enacted a pension funding ramp that shorted contributions throughout his term of office and caused contributions to dramatically increase around the time of the Great Recession. This backloaded payment schedule is a major contributor to Illinois’ massive unfunded pension liability.11 Along with so-called “pension holidays” in fiscal years 2006 and 2007 under former Gov. Rod Blagojevich,12 the Edgar ramp is a leading example of kicking the can down the road on pension contributions to relieve pressure on the budget.

Efforts to reform pension benefits to make them more affordable at both the state and local levels have so far been blocked by the Illinois Supreme Court.13 Without a constitutional amendment allowing future increases in pension benefits to be brought in line with what taxpayers can afford, pensions will crowd out core government services, encourage calls for tax hikes, and wreak havoc on the state’s finances and economy.

Illinois’ massive pension debt will lead to financial disaster

Illinois’ pension systems are in crisis

Illinois’ pension crisis is exceptional in its severity, but the Prairie State is not alone in facing huge retirement debts for government workers. State pension debt across all 50 states currently stands at about $1.4 trillion.14 This suggests a fundamental problem with the way defined-benefit pensions are structured.

According to a survey from The Pew Charitable Trusts, Illinois has the third-worst funding ratio for state pension systems, at 36 percent. In other words, the state only has 36 cents for every dollar of pension benefits currently promised. The only states with worse funding ratios are Kentucky and New Jersey, at 31 percent each.15 The average funding ratio for all states is 66 percent, or nearly double Illinois’ ratio.

However, Illinois’ unfunded pension liability is the worst in the nation as a percentage of GDP, according to Moody’s Investors Service.16 This is important because GDP is a measure of broad economic growth. A strong economy relative to the size of pension debts gives confidence to taxpayers and investors that the state has the ability to pay off its debts in the future without resorting to drastic spending cuts or tax hikes. Illinois is in the opposite position, with pension debts equivalent to about 29 percent of annual GDP.17 Nationwide, the average state pension liability as a percentage of GDP is just 7.1 percent.18

Officially, the state reports about $130 billion in unfunded pension liabilities.19 However, some estimates of the shortfall are significantly higher. Moody’s has said the state owes $250 billion more than it has on hand.20

Pension liabilities are extremely difficult to estimate accurately because they rely on a number of assumptions about things that will happen in the future, which is one of the fundamental flaws with defined-benefit systems. Assumptions include how many new workers will be hired, how fast salaries will grow, the rate at which people will retire, post-retirement life expectancy, and most importantly, the rate of return on investments made by the pension funds.

Investment returns are the single most important and variable factor affecting assumptions about future pension liabilities.21 If investments grow more than expected, the state can use fewer tax dollars to meet promised payments. However, if investments underperform, taxpayers are left contributing extra money to pay for retiree benefits, bailing out the system at the expense of current services.

Moody’s different estimate of unfunded liabilities is a result of different assumptions, such as investment returns. Moody’s uses a 5.67 percent rate of return and projects the amount of cash it would take to fully fund pension benefits over a 20-year period.22 Illinois’ official reporting uses investment returns of between 6.75 percent and 7.25 percent and a repayment schedule that targets 90 percent funding by 2045.23 In other words, Moody’s uses less optimistic assumptions and a shorter timeline to reach a higher level of funding.

This report uses the state’s officially reported numbers to measure the budgetary impact of pension contributions for a number of reasons.24

Of the five state pension systems, not one has even half of the money needed to fund future promises under current law.

On top of the $130 billion in debt from the five state pension systems, Illinois also has $56.9 billion in local pension debt. The state and many local governments also pick up the cost of retiree health care, and when one adds in the unfunded liabilities associated with those health benefits, each Illinois taxpayer is currently on the hook for about $56,000 in debt related to government worker retirement benefits.25

Pensions are crowding out other spending and threatening the future fiscal health of Illinois

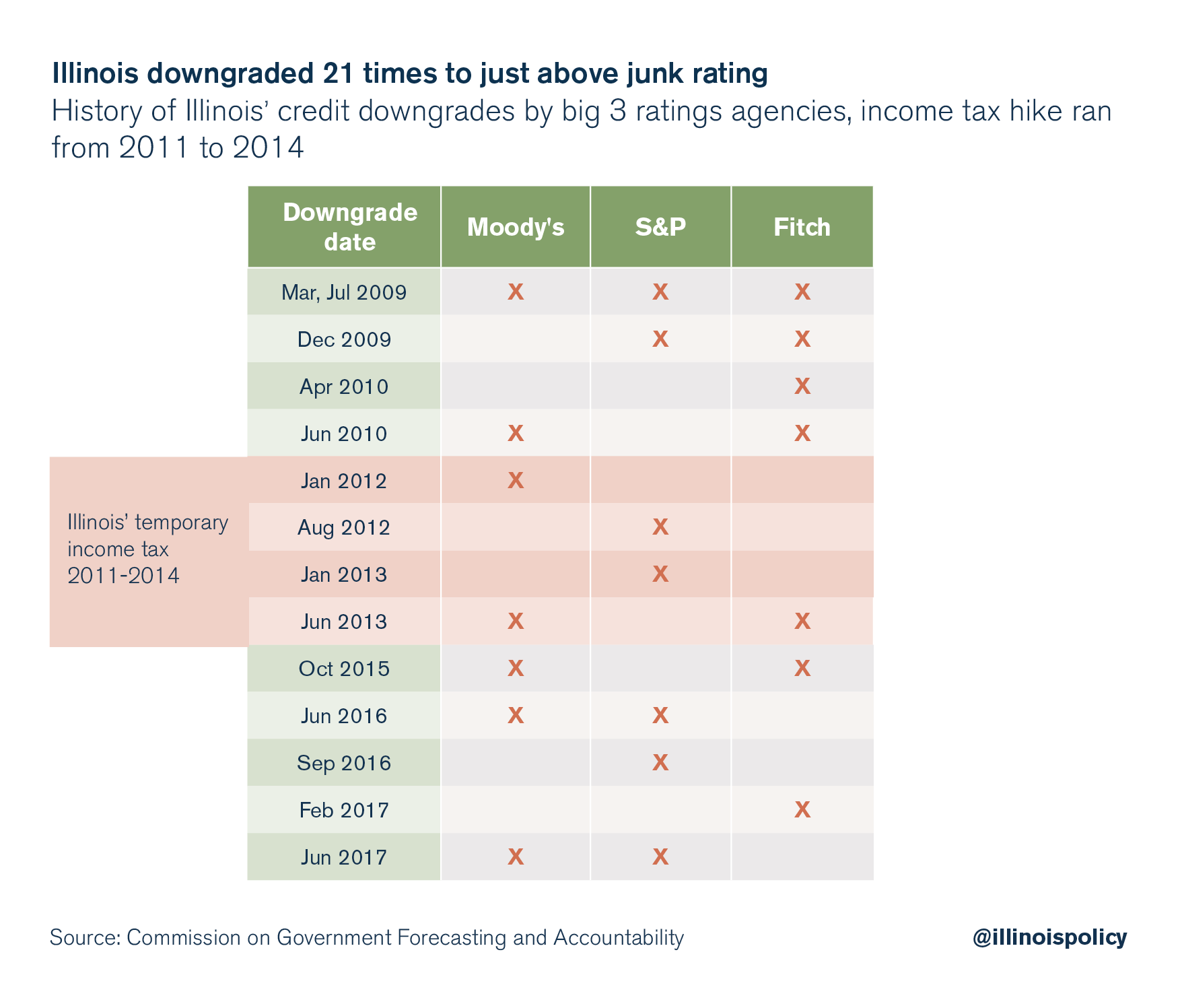

Illinois’ worst-in-the-nation credit rating is perhaps the most obvious sign of the negative effects of the pension crisis on the state’s overall fiscal health. Two major ratings agencies currently list Illinois just one notch above junk status, and pension debt is the leading cause.26

The state’s credit rating has been downgraded 21 times since 2009.

A poor credit rating makes it more expensive and difficult for Illinois to issue bonds, which hurts the state’s ability to invest in projects with a good rate of return, such as certain infrastructure improvements.27

Worse, expert literature has found that increased pension contributions can have negative effects on core government services, often called “crowding out.” American government experts have argued the United States is entering a “New Fiscal Ice Age” in which a given level of tax revenue purchases much less in current services because so much public money is being spent on the past in the form of retirement benefits.28

A study using a random sample of local governments found that this problem is widespread across the United States. Pension expenditures increased in 85 percent of cities sampled from 2005 to 2014 by an average of 69 percent after controlling for inflation.29 For example, Palatine, Illinois, saw expenditures grow to $7.4 million from $3.6 million in real terms over 10 years.30 Increases in pension spending caused decreases in both public employment and infrastructure spending in these cities, with the biggest crowding out effect seen in areas with pro-union collective bargaining laws and politically influential public sector unions.31

Government unions significantly influence politicians’ voting behavior on pension benefits32 and lead to increased spending on salaries and fringe benefits for government employees.33 In fact, the inclusion of public sector unions on pension boards might actually increase incentives to underfund pensions to the extent that it makes benefits appear cheaper than they actually are, making it easier for unions to lobby for benefit increases going forward.34

Illinois, which has very powerful public sector unions, provides a stark example of increased pension funding crowding out core government services at both the state and local levels.

According to the Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, growth in state spending on government worker pensions and employee health insurance has far outpaced spending growth in every other area.35 From 2000 to 2018:

- Spending on pensions has grown 663 percent

- Spending on employee health insurance has grown 215 percent

- Spending on pre-K through 12th-grade education has grown 65 percent

- All other spending has grown by just 16 percent

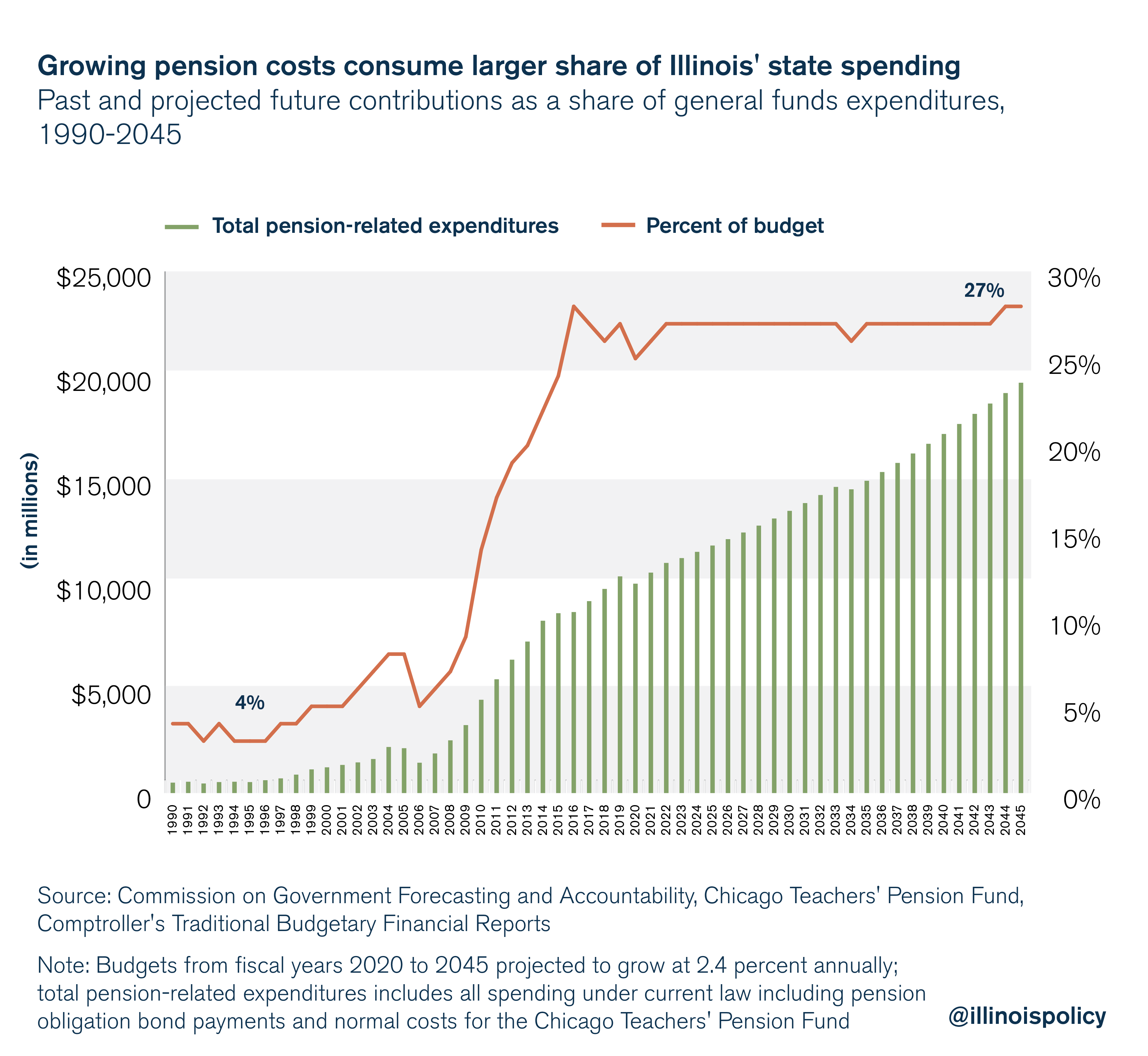

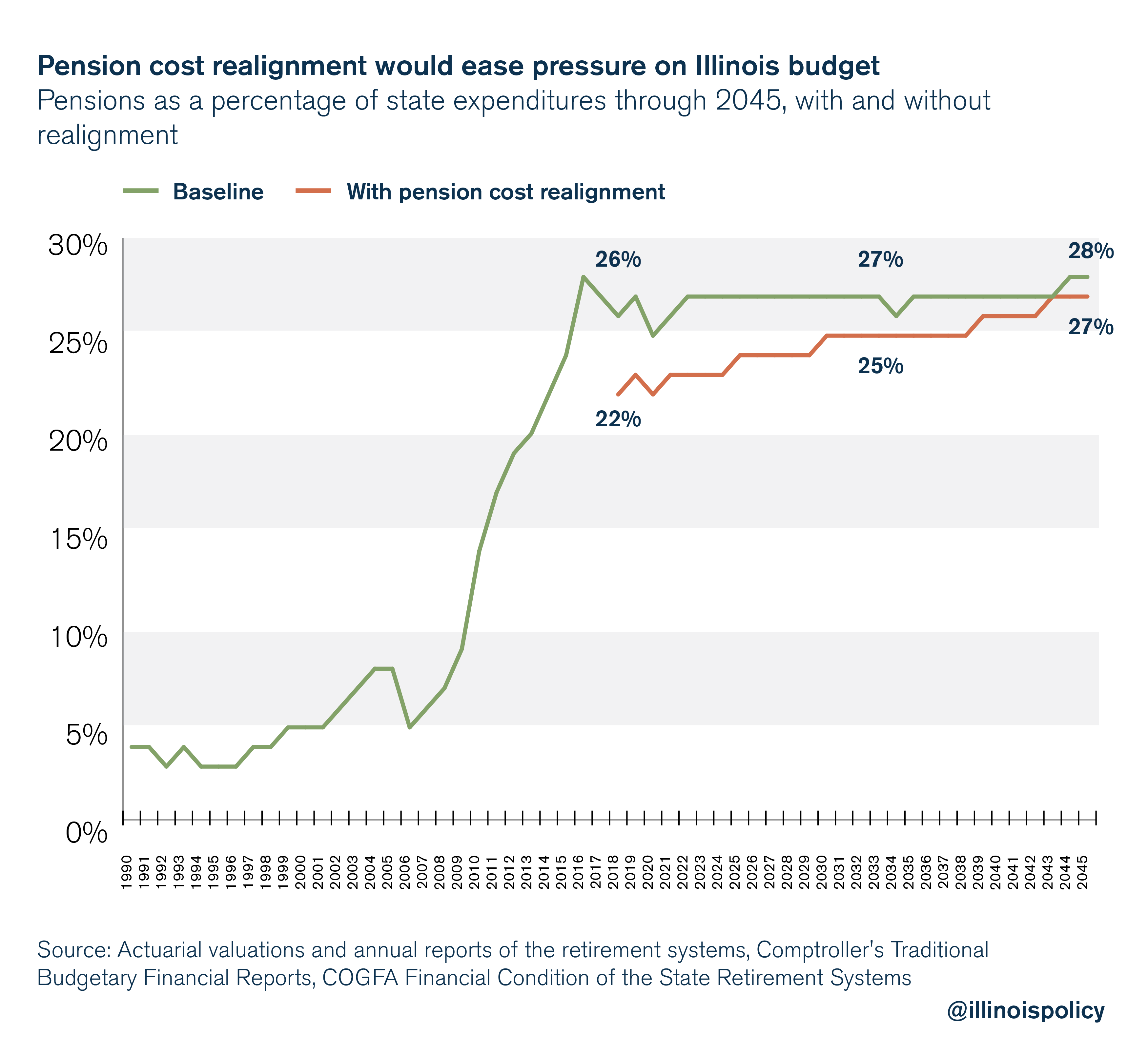

Total pension-related payments accounted for less than 4 percent of state expenditures in 1990. Going into fiscal year 2019, that share has now reached about 27 percent. Without a course correction, pensions will continue to consume over 25 percent of state spending annually for the next three decades, even if the state’s investment assumptions hold and the U.S. does not enter a recession. That means relatively less money for public safety and social service spending.

This projection assumes Illinois’ budget grows at just the long-term average of economic growth, or about 2.4 percent. Under this scenario, lawmakers would have little room to increase service levels without further tax hikes. Recent tax hikes are already harming Illinois’ economy and making the state’s long-run challenges more difficult to solve.36

A report produced for state Rep. Robert Martwick, D-Chicago, by the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability found Illinois would need to hike taxes by as much as 30 percent, or $224 billion, to cover current state promises on pensions and education from now until 2045.37

In other words, Illinois taxpayers will end up paying the same or more in taxes for fewer services in return, absent structural pension reforms.

If tax hikes are off the table as a solution – and they should be – lawmakers’ only remaining options are to structurally reform pensions so that they are in line with what taxpayers can afford going forward, or to allow pension spending to crowd out government services.

Crowding out effects can already be seen at the local level in Illinois. In Harvey, Illinois, pension obligations caused mass layoffs in the city’s police and fire departments.38 Because of a statutory provision that allows the state comptroller to intercept state money due to local governments that underfund their pensions, many other municipalities could soon find themselves in a similar situation. Over 50 percent of Illinois’ police and fire pension funds did not receive full payment in 2016, putting their municipalities at risk of facing the same choices as Harvey.39

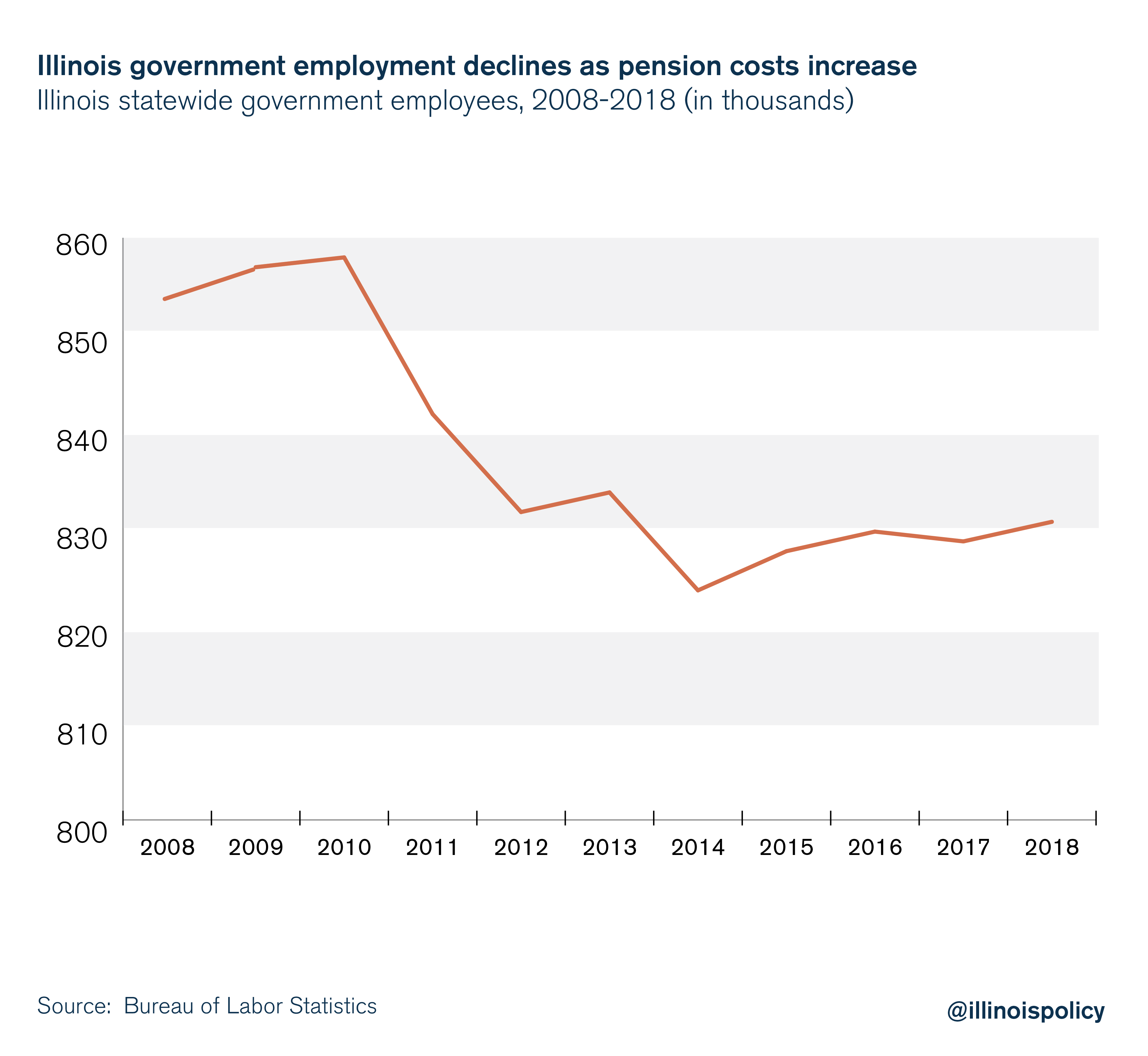

Public employment data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics suggest this may be a statewide problem. Since the dramatic increases in pension expenditures began in 2008 – resulting from the Edgar ramp40 – Illinois state and local government employment has been decreasing.

Taken together, the state’s poor credit rating and evidence of crowding out core services suggest Illinois needs to tackle its pension crisis sooner rather than later. Moody’s estimates that pensions, debt service and retiree health benefits will consume over 30 percent of revenue next fiscal year. If a national recession hits, that share could rise to 40 percent.41

This structural debt poses a serious threat to government retirees as well as taxpayers. If unexpected recessions or poor investment returns lead to insolvency of the funds, Illinois’ government retirees will find that the state’s pension protection clause cannot guarantee them a secure retirement.42

A modest reform effort in 2013 would have made important strides toward solving Illinois’ pension problem

In 2013, Illinois lawmakers took action to reduce the future growth in pension benefits, without reducing any earned benefits for retirees or current workers.

Public Act 98-0599, resulting from the passage of Senate Bill 1, was originally filed by Democratic Senate President John Cullerton, sponsored by Democratic House Speaker Mike Madigan, and signed by then-Gov.Pat Quinn, also a Democrat.43 The history of the bill shows that at one time the reality of Illinois’ pension crisis was apparent to bipartisan majorities of Illinois politicians, and that enough lawmakers on both sides of the aisle saw structural pension reform as necessary to restoring the fiscal health of Illinois.

The reform measures would have made a number of modest changes to future benefit increases as well as increased funding guarantees.

First, the bill required the state to target 100 percent funding by 2045. Under current law, even if every assumption works perfectly, the state’s pension system will never be fully funded, despite massive projected contributions. Current law only targets 90 percent funding by 2045, a violation of sound actuarial principles, according to the state actuary.44

In other words, current law guarantees that pension debt will still exist far into the future, even as taxpayers see contributions increase to nearly $20 billion annually.45

Perhaps the most important aspect of the 2013 reforms is that they would have had a dramatic and positive impact on the state’s finances.

According to actuarial projections at the time, SURS would have reached full funding by 2037 while TRS, SERS, and GARS would have all reached full funding by 2039.46

Furthermore, the state would have seen its fiscal year 2016 contribution reduced by $1.2 billion and unfunded liabilities decrease by $21.1 billion and $23.7 billion in fiscal years 2014 and 2015, respectively.47 Such savings could have made recent spending negotiations between Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner and the Democrat-controlled General Assembly significantly easier, potentially averting the state’s two-year budget impasse and subsequent permanent income tax hike.

Comparing projections under the reforms with projected contributions under current law shows how beneficial the structural changes to pensions would have been for the overall budget.

Under PA 98-0599, pension costs as a percentage of general fund expenditures would have fallen below 2 percent of annual expenditures by 2040, with total pension costs falling below $1 billion annually for the first time since 1998, according to actuarial projections at the time.

All of this would have been achieved without reducing the pension payment to any current retiree or reducing the amount already earned and promised to any current worker.48 Future benefit changes focused on three key areas:

- Gradually increasing the retirement age for current state workers under the age of 45

- Capping the maximum pensionable salary, with future growth in the cap pegged to inflation

- Eliminating 3 percent guaranteed post-retirement raises in favor of a COLA increase tied to inflation

Unfortunately, the Illinois Supreme Court ruled in 2015 that the pension protection clause of the state constitution protects not only earned benefits, but all potential future benefits as of the date an employee is hired by the state, striking down the 2013 reforms in their entirety.49 This restrictive interpretation has made even modest pension reforms difficult absent a constitutional amendment.

Lawmakers certainly could have foreseen the possibility of a court challenge and subsequent defeat of the reform. Had politicians included a constitutional amendment with their reform bill in the first place, they could have prevented a judicial setback. As it stands today, lawmakers have delayed action for five years and allowed the pension problem to worsen significantly.

Illinois Supreme Court’s precedent ties taxpayers to unreasonable standard

Under the Illinois Supreme Court’s 2015 precedent, a government worker’s pension benefits cannot be changed in any way after their first day working for the state. This precedent protects not only the benefits a worker has accrued – or earned to date – but also the formula under which those benefits will increase going forward. This view of pension protections is more restrictive than both the federal contracts clause and other state protections, and denies Illinois lawmakers the flexibility they need to make financial decisions necessary for the fiscal health of the state.

The Illinois Constitution states that “membership in any pension or retirement system of the State, any unit of local government or school district, or any agency or instrumentality thereof, shall be an enforceable contractual relationship, the benefits of which shall not be diminished or impaired.”50 This was the basis for the court striking down future benefit reforms.

Other state supreme courts have upheld pension reforms very similar to Illinois’ 2013 reforms, even when recognizing that pensions are contractual benefits that cannot be diminished or impaired.

For example, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that reductions in future cost-of-living increases did not violate retirees’ constitutional or contractual rights.51 The decision hinged on the differentiation between earned pension benefits, or vested base pension benefits, and future increases based on a COLA formula. According to the court, retirees in Colorado do not have an indefinite right to a particular COLA formula forever after their first date of hire.

Colorado’s decision is consistent with an analysis of contract rights and pensions by a legal expert who focuses on employment benefits, Amy Monahan. Many states now view pension promises as contractual rights – though some states guarantee them through less protective standards, such as promissory estoppel or property rights – but that does not mean all such states offer retirees the same level of protection as Illinois.52

For example, Hawaii’s constitution specifically states that only “accrued financial benefits” are protected, and courts there have interpreted this language as guaranteeing benefits already earned, but not the future growth in those benefits.53

Even under the most restrictive legal framework – such as Illinois’ precedent – states can still theoretically reduce benefits under their police powers if they can prove that doing so serves an important public purpose, and if the action undertaken to advance the public interest is reasonable and necessary. In order for an action to be considered necessary, (1) no other less drastic modification could have been implemented and (2) the state could not have achieved its goals without the modification. In practice, this standard is very difficult to meet, 54 and the argument failed in Illinois.55

The “earned, but not going forward” standard strikes a suitable balance between providing states with needed financial flexibility while still guaranteeing that no government workers will lose benefits they had a reasonable expectation of receiving and on which they might have based their decisions to work for their employers. Because only future benefits can be changed, workers maintain the ability to leave for a different job without risking past benefits if they no longer see the deal as in their interest.56

Other states that have seen success with reforming future benefits include Michigan, Arizona, Pennsylvania and Utah.57 Utah saw the need to reform pensions when annual pension expenditures reached 10 percent of the state’s general funds budget,58 a level Illinois reached in 2009 and nearly tripled in 2016.59

If Illinois passes a constitutional amendment to modify the pension protection clause, clarifying that it protects only earned benefits, it can achieve similar success in protecting taxpayers, the state’s fiscal health and public worker retirement security, all at the same time.

Quick win: Reforms Illinois can enact without changing the constitution

Changing the Illinois Constitution will take time. Any amendment needs to pass each chamber of the General Assembly with a three-fifths majority and then go to voters for approval on the ballot.60 The earliest this can be done is 2020.

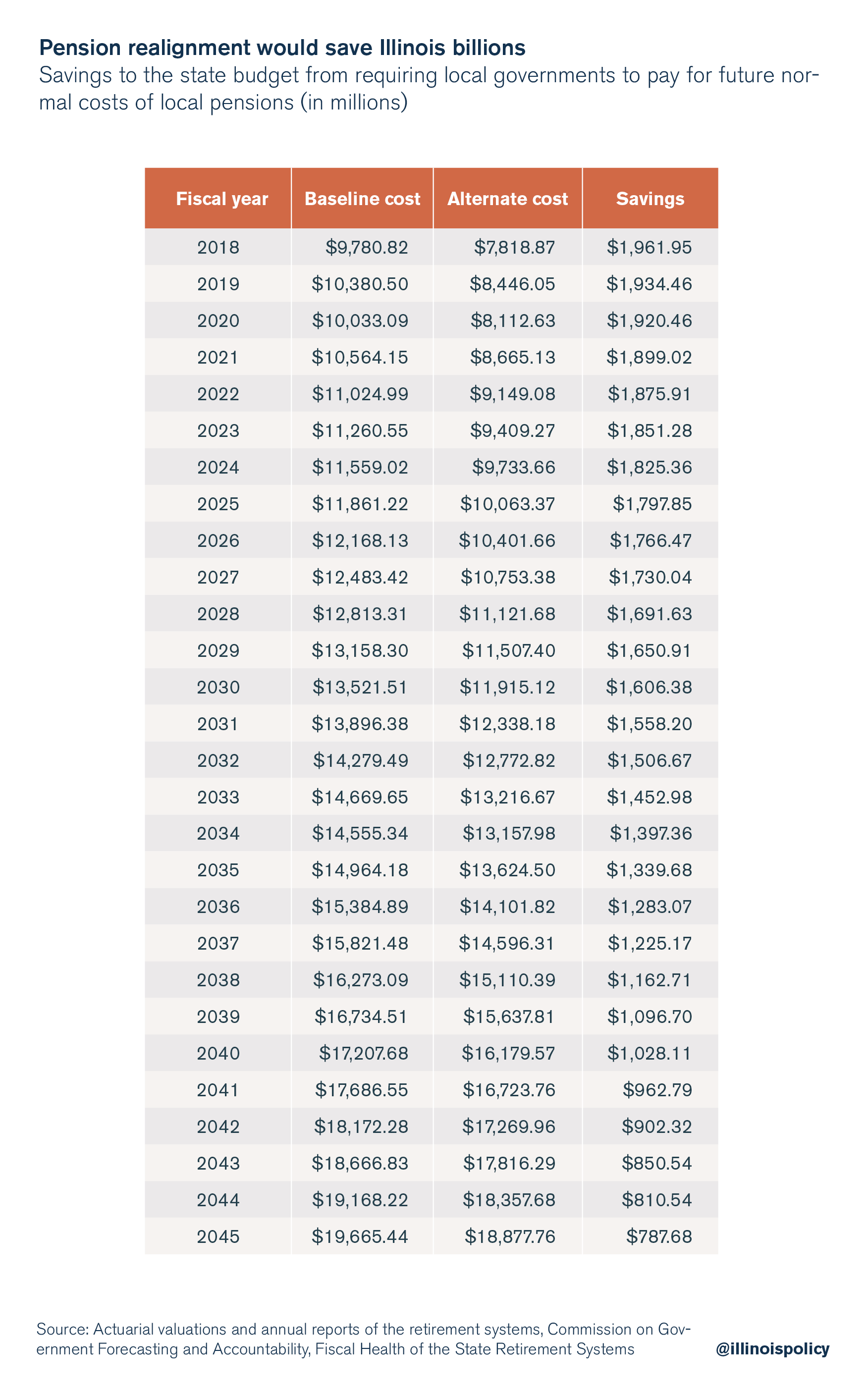

Moody’s Investors Service’s most recent analysis of Illinois’ finances makes clear that lawmakers cannot wait that long to start addressing the state’s structural spending challenges.61 In that report, the ratings agency spoke favorably about a plan proposed by Gov. Bruce Rauner to gradually realign local pension costs so that the one who pays the bill is the one who incurs the cost.

Under current law, the state of Illinois picks up the employer share of annual pension costs for schools and universities, as well as the cost of retiree health care for life.62 This policy creates a misalignment in incentives because local employers can dole out generous pension boosters in contract negotiations knowing that they will never feel the full cost.

The governor’s fiscal year 2019 proposed budget suggested phasing out this distortionary subsidy over four years.63 Savings for the first year would total $825 million, broken down as follows:

- $262 million by transferring 25 percent of the TRS normal costs

- $101 million by transferring 25 percent of the SURS normal costs

- $228 million by returning to the practice of Chicago Public Schools paying for the full normal cost of the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund, or CTPF

- $129 million by ending lifetime health insurance support for retired teachers

- $105 million by transferring some university group health insurance costs back to state universities

Fiscal year 2018 was the first year the state paid for the normal cost of the CTPF, which is why the proposal returned their full normal costs to the local level all in one year. Realignment of pension costs is a commonsense proposal to control the growth in pension benefits and reduce pressure on the state budget, which has repeatedly led to tax hikes. Combined with policies to reduce property taxes, properly aligning public retiree costs will protect taxpayers and help put Illinois back on a path toward fiscal solvency.

Requiring local school districts to pay the pension costs they incur going forward would only increase expenditures by an average of 2.5 percent per school district,64 which can be offset by reforms to better allow local governments to control costs, such as unfunded mandate relief. The current system of subsidizing local pensions is also highly regressive and against the state’s stated goal of providing increased funding to local schools with the least property wealth. Because teachers in wealthier districts have higher salaries, wealthy districts benefit disproportionately from the pension subsidy.65

A total realignment of the costs of local pensions would net significant savings for the state, reducing pension-related expenditures by nearly $2 billion a year for the next several years.

In the near term, these savings would ease the pressure of pensions on the state budget, buying lawmakers time to pass a constitutional amendment allowing for more substantive reforms in keeping with the defeated bipartisan 2013 reforms.

Unfortunately, the enacted fiscal year 2019 budget included none of these cost-realignment reforms. Lawmakers should adopt this commonsense solution as soon as possible.

Restoring Illinois’ fiscal health: Real, lasting pension reform

In addition to curbing government employee retirement costs by realigning resulting pension costs with salary and benefit decisions, saving Illinois from the fiscal abyss requires meaningful reform to pensions themselves. Such reform should come in two steps.

First, the state needs to stop the bleeding. Benefits for new hires must be doled out with an eye toward what taxpayers can afford. To an extent, the state has started this process through the implementation of a second tier of pension benefits for employees hired after Jan. 1, 2011. Tier 2 benefits come with more reasonable retirement ages, benefit increases that are tied to inflation and a maximum pensionable salary.66

However, because Tier 2 benefits are still part of a defined-benefit system, they rely on a number of assumptions that pose inherent risk to state finances. Additionally, Tier 2 is inherently unfair to younger government workers who by some calculations are paying more than they will receive in retirement benefits, subsidizing the more generous benefits of Tier 1 employees.67

A more secure and predictable plan calls for calls for mandatory 401(k)-style personal accounts for all newly hired employees, which could be modeled on the the successful, though currently optional, plan offered by offered by the State Universities Retirement System.68 Ending the defined-benefit system for future workers would ensure that spending on government worker retirement is secure and predictable going forward.

State lawmakers in Michigan, Alaska and Oklahoma have transitioned public pension systems to 401(k)-style plans.69

Second, the state needs to eliminate its unfunded liability. There are only two ways to do this: massive tax hikes or structural reforms. The tax hike route threatens to damage Illinois’ economy,70 chase more residents out of the state and impose on remaining Illinois taxpayers a future where they pay more for less, as pensions increasingly crowd out core government spending on public safety and social services.

Reform might be politically difficult – it demands lawmakers be honest with retirees about their promised retirement benefits – but it is possible, and far better for Illinois’ short- and long-term fiscal condition and economy. Because Illinois’ fiscal health has deteriorated further since the Illinois Supreme Court’s ruling, the medicine will need to be stronger than the 2013 reforms. Additionally, those reforms left the state spending close to one-fifth of annual expenditures on pensions for over a decade. Because of the deterioration of the state’s financial condition, and in order to achieve budget relief more quickly, lawmakers will need to modify the changes sought in the 2013 reforms. However, those bipartisan changes included in PA 98-0599 still provide a solid framework for the types of reforms Illinois should pursue conceptually.

A constitutional amendment allowing reductions in the growth of future benefits could be followed with legislation that essentially reintroduces the 2013 reform concepts with differences in degree, including the following:

- Increasing the retirement age for those not currently close to retirement

- A cap on the maximum pensionable salary that grows at a rate pegged to inflation

- Replacing Illinois’ 3 percent guaranteed benefit increases with a cost-of-living increase tied to inflation

- Potentially suspending COLA increases for certain years to allow inflation to catch up to past raises

By reforming future benefit accruals, Illinois will finally be able to provide a secure retirement for public employees without threatening the state’s credit rating and spending on core services.

Endnotes

- Benjamin VanMetre, “7 in 10 Fortune 100 Companies Provide Only Defined Contribution, 401(k)-Style Retirement plans”, Illinois Policy Institute, July 25, 2013.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klinger, “Pensions 101: Understanding Illinois Massive, Government-Worker Pension Crisis,” Illinois Policy Institute, February 2016.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klinger, “Pensions 101”.

- Excludes Alaska’s one-time surplus cash infusion, National Association of State Retirement Administrators, “State and Local Government Spending on Public Employee Retirement Systems,” March 2018.

- Pub. Act 86-0273.

- Leonard Gilroy, Anthony Randazzo, and Pete Constant, “Arizona Reforms Second Public Safety Pension Plan,” Reason Magazine, April 17, 2017.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klinger, “What’s Driving Illinois’ $111 Billion Pension Crisis: Retirement Ages, COLAs and Out-of-Sync Pension Payouts,” Illinois Policy Institute, April 2016.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klinger, “Pensions 101.”

- Ted Dabrowski, “The Edgar Ramp: The ‘Reform’ that Unleashed Illinois’ Pension Crisis,” Illinois Policy Institute, October 27, 2015.

- Pub. Act 94-0004.

- Adam Schuster, “Chicago Park District Pension Reform Ruled Unconstitutional,” Illinois Policy Institute, April 5, 2018.

- Pew Charitable Trusts, “The State Pension Funding Gap: 2016,” April 12, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Moody’s Investors Service, State of Illinois in Depth, “Pension Burden Will Erode Credit Without Offsetting Actions,” May 30, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Moody’s Investor Services, “Medians Show US State Net Pension Liabilities Tick Higher in Fiscal 2016,” September 13, 2017.

- Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, “Financial Condition of the State Retirement Systems as of June 30 2017,” Updated May 2018.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klinger, “Illinois Owes Over $250 Billion in Pension Debt”, Illinois Policy Institute, June 1, 2017.

- National Association of State Retirement Administrators, “Public Pension Plan Investment Return Assumptions,” February 2018.

- Moody’s Investors Service, Adjusted Net Pension Liability Methodology, April 13, 2017.

- State Actuary’s Report, Office of the Auditor General, December 2017.

- For several reasons, Illinois official reporting is a better measure to use when estimating the impact of pension spending on the budget, regardless of which measure more accurately reflects the liability. First, the future contribution levels in official reporting are reflective of current law, which means they more closely match what will actually be paid. Second, the state actuary performs an audit of the state pension system each year and has found that the investment return assumptions are generally reasonable compared to the systems’ historical rates of return. In fact, each of the state pension systems has significantly outperformed its assumed rate of return in recent years. Third, even Moody’s uses the state’s officially reported numbers in its most recent analysis of Illinois’ fiscal health, and the ratings agency admits that its methodology is primarily useful for comparing across states and should not be used as a set of guidelines for state reporting. Lastly, the official numbers tell a bad enough story on their own.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klinger, “Each Illinois Household On the Hook for $56k in Government-worker Retirement Debt”, Illinois Policy Institute, March 23, 2017.

- Adam Schuster, “Illinois Bonds Once Again Rated Just Above Junk,” Illinois Policy Institute, April 10, 2018.

- Adam Schuster, “Bad Budgeting Basics: How Illinois’ Budget Process Hurts Taxpayers,” Illinois Policy Institute, Spring 2018.

- D. Roderick Kiewiet and Mathe D. McCubbins, 2014, “State and Local Government Finance: The New Fiscal Ice Age,” Annual Review of Political Science, 17: 105-122.

- Sarah F. Anizia, 2017, “Pensions in the Trenches: Are Rising City Pension Costs Crowding Out Public Services?” Goldman School of Public Policy Working Paper: University of California, Berkley.

- Ibid p. 16

- Ibid p. 29-35

- Sarah F. Anzia and Terry M. Moe, 2017, “Polarization and Policy: The Politics of Public Sector Pensions,” Legislative Studies Quarterly 42 (1): 33-62.

- Sarah F. Anzia and Terry M. Moe, 2015, “Public Sector Unions and the Costs of Government,” Journal of Politics 77(1): 114-127.

- Sarah F. Anzia and Terry M. Moe, 2017, “Interest Groups on the Inside: The Governance of Public Pension Funds,” Working Paper, Goldman School of Public Policy.

- Governor’s Office of Management and Budget, “Fiscal Year 2019 Operating Budget Book.”.

- Adam Schuster, “Failure: On the Anniversary of Illinois’ 2017 Tax Hike,” Illinois Policy Institute, July 3, 2018.

- Rich Miller, “Think that Progressive Tax Will Fix Illinois Finances? Well…,” Crain’s Chicago Business, May 4, 2018.

- Adam Schuster, “Harvey Pension Crisis Leads to Mass Layoffs,” Illinois Policy Institute, April 11, 2018.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klinger, “Harvey, the First Domino in Illinois: Data Shows Nearly 400 Other Pension Funds Could Trigger Garnishment,” Wirepoints, April 16, 2018.

- Ted Dabrowski, “The Edgar Ramp.”

- Moody’s, State of Illinois in Depth, May 30, 2018.

- Amy B. Monahan, 2016, “When a Promise is Not a Promise: Chicago-style Pensions,” UCLA Law Review 64, Minnesota Legal Studies Research 16-17.

- Illinois General Assembly, Bill Status of SB0001, 98th General Assembly.

- Office of the Auditor General, “State Actuary’s Report”, December 2017.

- Illinois Policy Institute calculations based on systems’ pension data.

- Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, “Financial Condition of the Illinois State Retirement Systems”, June 30, 2013.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Pension Reform Litigation v. Pat Quinn, IL Supreme Court 2015 IL 118585.

- Illinois Constitution, Article XIII, Section 5.

- Justus v. State of Colorado, Supreme Court Case No. 12SC906, October 20, 2014.

- Amy B. Monahan, 2010, “Public Pension Plan Reform: The Legal Framework,” Education Finance Policy, 5(4): 617-646, Minnesota Legal Studies Research 10-13.

- Ibid.

- Ibid p. 19.

- Pension Reform Litigation v. Pat Quinn. “Under all of these circumstances, it is clear that the State could prove no set of circumstances that would satisfy the contracts clause. Its resort to the contracts clause to support its police powers argument must therefore be rejected as a matter of law.”

- Ibid p. 34-35.

- Dan Liljenquist, “Pension Reform Comes in Many Shapes and Sizes,” Forbes, December 8, 2017.

- Ibid.

- Illinois Policy Institute calculations of data obtained from five state retirement systems

- Ill. Constitution, Article XIV, Section 2.

- Moody’s, State of Illinois in Depth, May 30, 2018.

- Adam Schuster, “Civic Federation Calls for Tax hikes, Opposes Sensible Reform in Budget Criticism,” Illinois Policy Institute, May 17, 2018.

- GOMB, Fiscal Year 2019 Operating Budget Book.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klinger, “Illinois Regressive Pension Funding Scheme: Wealthiest School Districts Benefit Most,” Wirepoints, March 9, 2018.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klinger, “Education Finance Solutions”, Illinois Policy Institute, Spring 2017.

- Public Act 96-0889 for state employees, Public Act 96-1495 for local government employees.

- Mark Glennon, “The Tier 2 Pension Mess in Illinois”, Wirepoints, January 16, 2014.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klinger, “Pension Reform Plan for Illinois: Right Under its Nose,” Illinois Policy Institute, March 24, 2017.

- Ben VanMetre, “Take note, Illinois: Transition Costs Not an Issue in Pennsylvania’s Pension Reform”, Illinois Policy Institute, March 30, 2015.

- Orphe Divounguy, Bryce Hill, and Joe Tabor, “Why the 2017 Tax Hike Will Harm Illinois’ Economy”, Illinois Policy Institute, Winter 2018.