Tamales y temor: The world of Chicago’s shadow chefs

By Austin Berg

Respect

“Every day, every year; summer, winter. These people don’t stop,” says Mario Gonzalez, flanked by hundreds of pallets of imported foods, stacked as high as the warehouse ceiling.

He’s the assistant manager at La Hacienda, a grocery wholesaler on Chicago’s southwest side.

“[Food-cart street vendors] aren’t a majority of our business, but I’ll say this: We open at 5 a.m. every day … they’re here before that, waiting. It makes me feel good that we can serve them.”

Two salespeople for La Hacienda are singing similar praises in a nearby parking lot. Sylvia Kestler mentions how they help poor people who have no intention of paying them back. Andrea Caballero says she remembers speaking to them since she was little.

Food-cart street vendors command respect in communities across Chicago – from those selling chicharrones and shaved ice in Little Village and Pilsen to the tamaleras in Albany Park.

But not in City Hall.

In Chicago, it’s illegal to sell prepared food out of a cart. Only whole, uncut fruit and frozen desserts are permitted. Sell anything else and you risk reprisal from law enforcement.

Risk

Claudia Perez, a 62-year-old tamale vendor who operates in Little Village, tells of a police officer who threw her food away, calling it trash. Meant for hungry construction workers in Little Village, her tamales were strewn across Chicago concrete instead.

Joaquina, who sells chicarrones (fried pork rinds) and shaved ice on 26th Street, has tried to improve relations between the police and vendors like herself.

“I’ve been trying to help other vendors to see how best to work with police. If they say ‘you need to leave’ we need to pack up and leave, even if there are 20 customers,” she says. “They are the authority … the alternative is that the police officer gets mad and throws away your food, handcuffs you, takes you away.”

Interactions with police aren’t always adversarial. Cecilia, another street vendor on the southwest side of the city, says police officers buy tamales from her cart three times a week. But they also harass her occasionally.

Cecilia wakes up at 2 a.m. most days to prepare those tamales, selling them through breakfast and lunch hours, after which she heads to her shift at a factory job at 1 p.m. She works to support her three children.

Vendors not only risk wrongdoing in the eyes of law enforcement, they also operate in communities that present serious safety risks. Claudia was recently robbed while pushing her cart before dawn in Little Village. Two men grabbed her, threw her in their truck, took her to a nearby bank and demanded she withdraw money. Claudia lost $4,000, a large chunk of her savings.

“Of course I’m scared. But god willing I will stay safe,” she says.

Reason

Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel has promoted mobile vending as a solution to the city’s food deserts – areas where people lack access to fresh, nutritious food – but he has withheld praise for the sustenance offered by hundreds of Chicagoans already operating in those areas.

Emanuel held a press conference on July 10 to herald the launch of a city-funded “produce bus” project called Fresh Moves. This is the second rollout of the program after the buses posted more than $200,000 in losses from 2011 through 2012, according to the Chicago Tribune.

Directing more public money toward providing fresh food to underserved areas is an affront to the Chicagoans struggling under the boot of City Hall to do just that.

As anyone who’s walked down 26th street on a summer day can tell you, there’s no shortage of Chicagoans trying to feed their communities – the city need only unleash them.

An ordinance that would immediately allow thousands of food-cart street vendors the freedom to serve their communities sits before Emanuel’s City Council, and along with it the potential for explosive growth in the industry. New research from the Illinois Policy Institute indicates city aldermen should act to pass it.

Reconnaissance

For many who hear stories of struggle from Chicago’s street vendors, the solution seems simple: legalize street food. This response has taken the form of an ordinance introduced in City Council on May 20, which would let most of these vendors seek permission from city government to sell their fare.

Of the largest 25 cities in the U.S., Chicago is one of only two cities that do not allow food-cart street vending.

Reluctance to embrace food carts comes at a high cost to the city and its residents, new research from the Illinois Policy Institute shows. Legalization would be a boon for both entrepreneurs and city coffers.

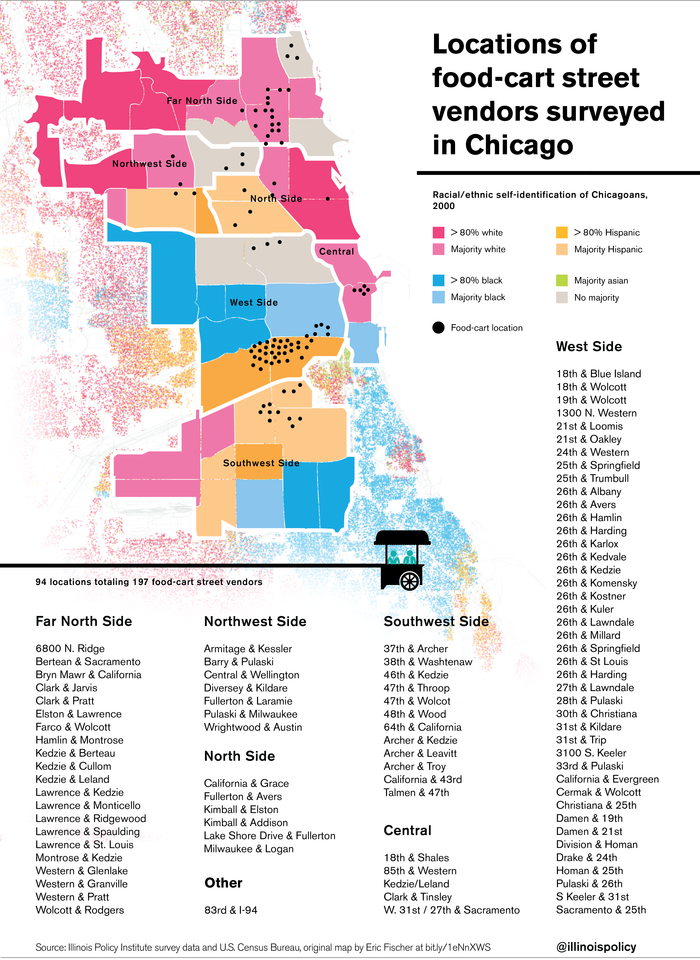

According to Institute analysis of survey data from nearly 200 of the estimated 1,500 food-cart street vendors across Chicago, food carts generate an estimated $35.2 million in annual sales, $16.7 million in annual income, 2,100 jobs and as many as 50,000 meals served per day. Food-cart street vending earnings support over 5,000 dependents.

The survey data also give insight on broader trends among Chicago’s food-cart community.

The average food-cart street vendor in Chicago is a Hispanic, middle-aged woman from Little Village or Pilsen. She supports three dependents with her earnings, which come from serving dozens of customers daily. She often risks ticketing for selling food (nearly 40% of vendors surveyed told researchers they had been ticketed at least once).

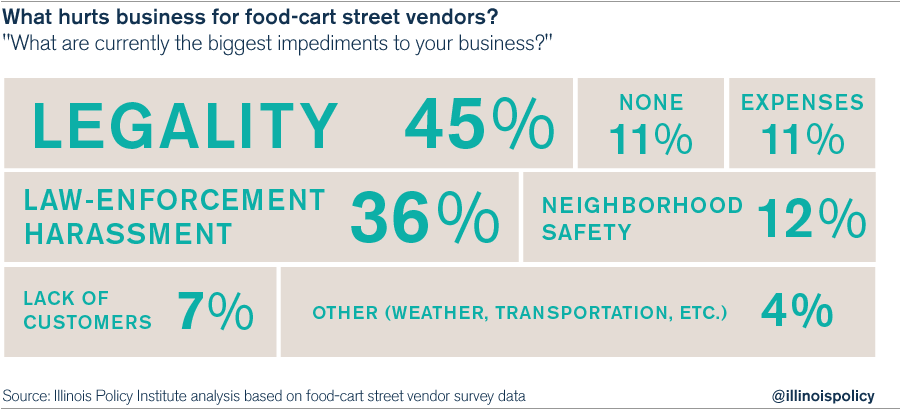

Legality of the trade is the biggest impediment to business growth for food-cart street vendors.

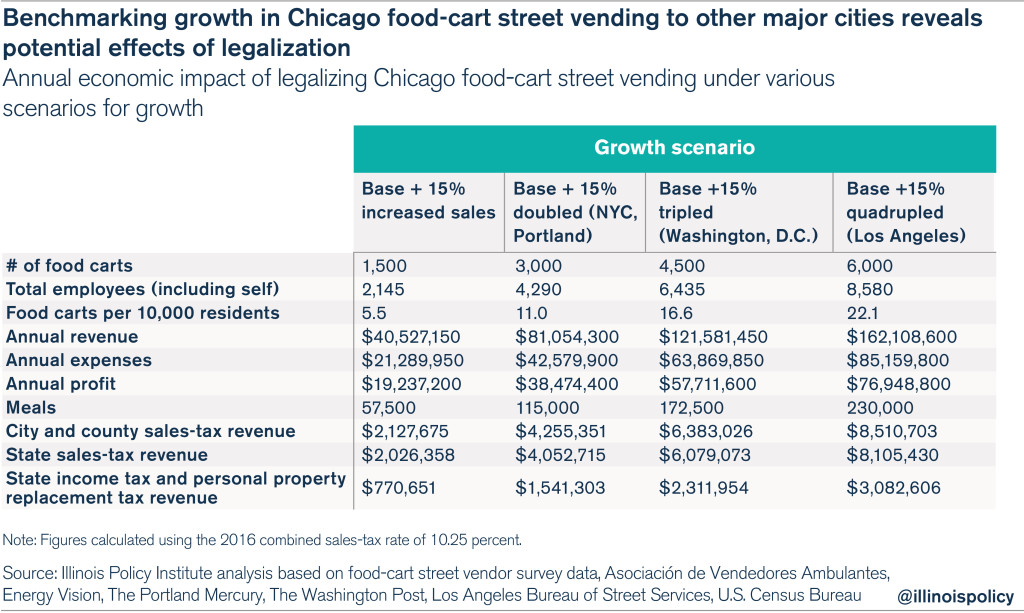

By pegging Chicago’s food-cart street vendor population to cities with more liberal legal climates, the Institute was able to estimate the potential impact of food-cart legalization.

Los Angeles, where a ban on food carts is enforced on a complaint basis only and a massive geographical area allows vendors to operate relatively unencumbered, is home to 25.8 food carts per 10,000 residents. That number is just 5.5 in Chicago. If legalization yielded a food-cart industry approaching the size of Los Angeles’, the Windy City would gain:

- 6,400 new jobs

- $127 million in new retail sales

- $60 million in additional income

- $8.5 million in city and county sales-tax collections

- 180,000 additional meals served each day

Looking past potential growth in income, jobs and fresh meals for Chicago communities, the estimated increase in tax revenue is notable given the city’s junk-rated finances. With limited ability to raise taxes without driving residents out of Chicago city limits, legalizing hundreds of legitimate, minority-owned businesses and reaping the associated tax revenue would be a win-win for politicians.

Rising

For Chicago’s food-cart street vendors, legalizing their trade means much more than just being able to expand their businesses, as 80 percent of survey respondents said they would.

It means living in a city that embraces the entrepreneurial spirit of immigrant families. It means being able to prove to future generations that hard, honest work can bring success, even in difficult circumstances.

It means being able to serve good food to hungry people without fear of legal repercussions – just like tens of thousands of Americans in other major cities do from food carts every day.

In the eyes of Claudia Perez, permission to succeed in the eyes of city government would mean “everything.”