The novel coronavirus, COVID-19, is creating volatility and uncertainty in financial markets and among businesses across the globe. Every state government will face serious fiscal and economic challenges as a result.

But Illinois is uniquely vulnerable.

Without preventative policy action, Illinois could face a state budget deficit of $6.3 billion more than expected, widespread job losses as businesses struggle to cope with reduced economic activity, and a slide toward insolvency for the state’s pension systems.

Health professionals, business leaders and government officials have united to take drastic, necessary action to combat the spread of the disease, including cancelling large gatherings and educating the public on “social distancing.” Gov. J.B. Pritzker also announced an order requiring restaurants and bars statewide to close their doors to dine-in customers. These actions follow from the advice of public health professionals regarding minimizing human contact to “flatten the curve” of transmission, a concept explained in depth by the Washington Post.

These severe measures underscore the seriousness of the coronavirus pandemic.

Likewise, policymakers must take the pandemic’s economic and financial risks seriously, and take significant steps to mitigate harm for state residents. The Illinois Policy Institute proposes the following policy responses:

- Targeted tax relief to save jobs: In order to help businesses cope with lost revenue and prevent layoffs, the state of Illinois should mandate that all local governments delay the collection of one installment of this year’s business property tax payments until at least Oct. 1. State officials can make use of emergency borrowing authority granted in the state constitution to issue short term bonds of about $6 billion – equal to 15% of this year’s appropriations as the constitution allows – to cover the temporary loss to local governments.

- Remove barriers to maximizing the supply of medical care:

-

-

- Illinois should consider suspending “certificate of need” laws that impose restrictions on acquiring new medical equipment, expanding the number of beds available, and changing the scope or function of existing medical facilities.

- Evaluate nurse and medical licensing reciprocity with other states to make it as easy as possible for out-of-state medical practitioners to operate in Illinois during the outbreak.

- Evaluate scope of practice regulations to ensure that non-physician medical professionals, such as nurse practitioners, are able to provide as many services as possible.

-

-

- Reform state pensions to help cover budget holes without economic harm: The Illinois Policy Institute’s pension reform plan would enable the state to save $2.4 billion on this year’s pension payment by reducing the growth in unearned future pension benefits, without taking away a single dollar earned by retirees or current workers. This is the only major budgetary response that would not reduce aggregate demand in the economy because outlays from the pension funds, or checks going to retirees, are made independently of state contributions to the funds. No retiree checks would be reduced, so there would be no harm to consumption expenditures during the crisis.

While all states would face challenges if COVID-19 triggers a recession or prolonged market downturn – including lost revenue, automatic spending increases in means-tested programs, growing budget deficits and lost investment assets – decades of mismanagement have left Illinois with the worst budget health in the nation, making the risks particularly severe here.

Other states with high fixed costs and large public debt burdens, including New Jersey and Kentucky, among others, are also at acute risk and should take action to shore up state finances as soon as possible.

The following is an assessment of the risks the COVID-19 outbreak poses to Illinois’ budget, local governments and pension systems, with details on how proactive policy can mitigate these risks.

Fallout risk No. 1: Increase in the budget deficit of up to $6.3 billion

If a recession occurs, Illinois would be hit by inevitable declines in revenues and required automatic increases in means-tested programs. The largest automatic spending increases would be in Medicaid as rising unemployment and falling income increase eligibility for the program.

Last year, Moody’s Investors Service conducted a “stress test” to see how a recession is likely to affect state budgets. For Illinois, a moderate recession would mean a more than $4 billion budget hit, with tax revenues coming in $3.4 billion lower and Medicaid spending jumping by $674 million, according to Moody’s analysis. A severe recession of close to the same magnitude as the Great Recession would cause deficits to jump by $6.3 billion, with $5.5 billion in lost revenue and $770 million in increased Medicaid spending.

These projections roughly track with the effects of the last recession in Illinois.

As a result of the 2008 financial crisis and ensuing recession, Illinois’ total tax revenues came in 9.4% below expectations in fiscal year 2009. A similar drop in total tax revenue for next year’s budget would mean $3.83 billion in lost revenues. Corporate and personal income taxes dropped even further than overall revenues – nearly 12% each – underscoring their volatility compared with other sources of tax revenue.

These deficits would likely prevent the state from funding government programs at adequate levels during a recession and would grow the backlog of unpaid bills – which sits at close to $7.5 billion as of March 17 – leaving state vendors awaiting payment at a time when they can least afford to carry the state’s debts and leaving residents without needed services.

The state currently has no cushion to absorb these higher budget deficits, much less manage the hit to the pension system. Illinois has not managed to truly balance a budget – meaning spending came in lower than revenues in actual practice, rather than just on paper – since 2001. Decades of spending more than the state brings in has left Illinois with significant high-interest debt and very little in reserve funds.

The Prairie State’s “rainy-day fund” – which states are supposed to use to help pay bills during a recession without economically harmful tax hikes or spending cuts – is essentially empty. The $1.189 million Illinois had saved as of March 13 is equal to just .002% of last year’s $40.2 billion budget, or roughly enough to cover 15 ½ minutes of state spending. From 2005 to 2018, the Illinois Policy Institute found Illinois ranked 45th out of 50 states in rainy day savings because politicians frequently swept the fund for non-emergency purposes and failed to make deposits during periods of growth. Experts recommend states save between 5% and 10% of annual expenditures to cover the lost revenues and automatic spending increases caused by a recession.

Fallout risk No. 2: Shock to the pension funds could start a slide to insolvency

Asset loss in state and local pension funds could trigger a slide to insolvency while increasing the cost of what is already the largest budget category for the state and many cities. Further decline in pension funding ratios and corresponding increases in debt are also likely to trigger a credit downgrade, making Illinois the first state to drop to junk status and raising the cost of borrowing.

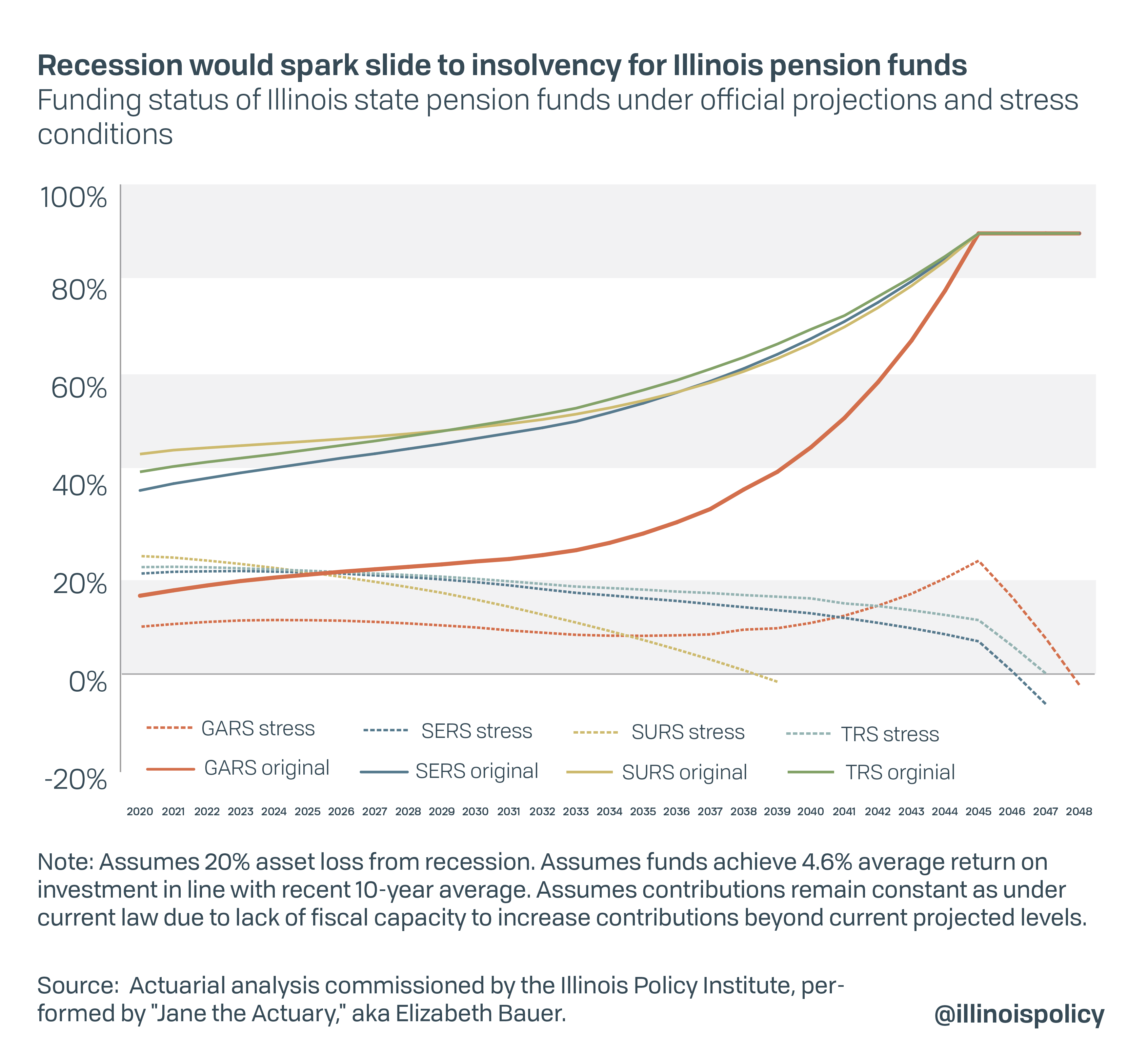

An actuarial stress test of state pension funds commissioned by the Illinois Policy Institute last fall shows that another major recession without structural reform could trigger a slide to pension insolvency, leaving the state without the means to pay benefits promised to retirees. The State Universities Retirement System would run out of money first in 2039, followed by the remaining state systems.

The stress test assumes a 20% loss in asset value in pension investments, the same loss experienced in 2009, and that funds would average the same roughly 4.6% rate of return on investment they achieved in the decade after the last recession. Because total pension costs including debt service and pension subsidies to Chicago Public Schools already exceed $10 billion and more than 25% of the state budget, Illinois has virtually no fiscal slack to significantly increase pension funding beyond current levels and prevent this decline.

Stock markets have been highly volatile in recent days and weeks, with steep losses followed by sharp rebounds and then further losses. On March 11, the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed 20.3% below its Feb. 12 high point, and the S&P 500 was down 19% from its peak, according to the Wall Street Journal. While it is so far unclear if these losses will be made up later in the year, a 20% annual loss in the funds appears quite possible. Over the past decade, the pension funds have experienced years of loss even while the economy was growing.

Previous recessions also significantly increased annual pension costs to the state, with direct contributions in 2010 exceeding official state projections from before the financial crisis by 14.2%. When pension funds lose assets, the unfunded liability grows and taxpayers must generally make larger payments on the debt. However, as part of the 2018 budget, lawmakers now require unexpected increases in pension funding to be spread evenly across five years. That means the increased budget cost will be mitigated in the first year after a recession, but the pension debt will grow faster than it otherwise would due to artificially lower contributions.

Solutions: How proactive reform measures can mitigate the financial fallout of COVID-19

It’s important to note that significant uncertainty remains regarding the economic impact of the virus. A recession is possible, but not assured. Illinois’ elected leaders can help prevent the worst-case scenario with bold, proactive steps today.

Chetan Ahya, chief global economist for Morgan Stanley, wrote that his team does not think the virus will “fundamentally challenge the growth cycle” in the long term. In two of the three possible scenarios they present, growth will be depressed for the next three months but could rebound as early as this summer with appropriate preventative actions. A recession is defined as two consecutive fiscal quarters, or 6 months, of economic contraction rather than growth.

On the other hand, some bond investors told the Bond Buyer that the sell-off caused by COVID-19 was “worse for the market than the aftermath of September 11th and the 2008 financial crisis combined.” The panic in financial markets is why former deputy director of the International Monetary Fund, Desmond Lachman, warns against writing off the risk of a recession: “Serious coronavirus-related economic troubles in systemically important countries abroad could soon trigger a financial and economic crisis in the United States.” Lachman argues the federal government must take significant preventative action now, rather than get caught “flat footed” after the fact.

Indeed, the federal government has already indicated a willingness to take emergency action through both fiscal and monetary policy. The Federal Reserve has slashed interest rates to near zero and announced plans for $700 billion in stimulative bond purchases, among other measures. The U.S House of Representatives has already passed two major pieces of legislation, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, which were negotiated with White House representatives. Key provisions would provide emergency funding for relevant agencies, impose paid leave mandates on private employers, provide job security for the quarantined and increase federal aid to states for poverty alleviation, including raising the Medicaid reimbursement rate.

However, the threats to Illinois’ finances are so large, state leaders should not count on the federal government closing all the holes. The $1.56 billion stimulus Illinois received in 2010 only accounted for 54% of lost revenue.

Unfortunately, Illinois has limited options it can take on its own due to its poor financial health.

Many government programs cannot be targeted for cuts without negatively impacting service quality. Since fiscal year 2000, after adjusting for inflation, state spending on a range of core government services including aid to the poor, public health, and public safety has been reduced in real terms by 32% as it was crowded out by a more than 500% increase in pension spending. Programmatic spending cuts during or before a recession also risk deepening the contraction by reducing aggregate demand.

On the revenue side, Illinois already has one of the highest state and local tax burdens in the country. And raising taxes during a recession would cause significant economic harm. Often, governments look instead to cut taxes during a recession as a form of economic stimulus.

While stark, none of these factors mean Illinois is powerless in deciding its own fate. Springfield should pursue proactive reform in at least the following three areas:

1) Grant temporary property tax relief to businesses to encourage hiring and minimize job losses

Because property taxes are often the biggest burden Illinois government places on taxpayers, tax relief stimulus should start there. The combination of mandatory restaurant closures, voluntary isolation, and cancelled events will significantly reduce business income in affected and connected sectors. Asking these businesses to pay thousands of dollars or more in property taxes would be irresponsible at this time and risk forcing businesses to resort to layoffs to prevent from going under.

Pritzker and the General Assembly should pass emergency legislation delaying collection of one half of this year’s business property tax payments for all local governments. Property tax payments are generally due in two installments. Business property taxes apply to commercial, industrial, agricultural, railroad and mineral property. The first payment in Cook County was already due March 3, but the second installment, which is usually due in August, should be delayed until Oct. 1 to help businesses and workers. Most other counties do not collect the first installment until June and could delay taxpayers’ first payment until at least Oct. 1, when the viral threat could be reassessed.

The state of Illinois could cover the lost local revenue with emergency borrowing. The state constitution reads:

“State debt may be incurred by law in an amount not exceeding 15% of the State’s appropriations for that fiscal year to meet deficits caused by emergencies or failures of revenue. Such law shall provide that the debt be repaid within one year of the date it is incurred.”

After the last recession, the state used this authority to issue $1.3 billion in bonds for the operating budget. Today, this provision would allow for a little over $6 billion in emergency bonds given this year’s $40.14 billion budget. The bonding would allow Illinois to provide tax relief where it is needed most without harming local government finances. Because the bond must be repaid within the year, the interest cost could be relatively minor and covered by modest changes to the fiscal year 2021 budget. The principal of the debt would be repaid by counties when they collect the delayed installments.

According to the most recent data from the Illinois Department of Revenue, property tax collections across all business types equaled just under $11.5 billion in 2018. Deferring half of that amount would cost $5.74 billion, less than the state’s emergency bonding authority.

2) Loosen health care industry regulations to provide needed medical resources

To help mitigate COVID-19’s spread and effects, Springfield should consider reducing regulatory barriers to the supply of medical care. One place to look would be certificate of need, or CON, laws, which allow state regulators to limit growth in the supply of medical facilities and equipment to the benefit of established medical providers. Jeffrey Singer, a medical doctor and senior fellow at the Cato Institute, has warned that CON laws must be waived to guard against the threat of a breakdown in the hospital system, which could become flooded with new patients.

Other areas that should be evaluated for undue barriers to medical supply include scope of practice laws – which define which type of work that can be performed by mid-level or non-physician medical professionals – and interstate licensing reciprocity. Illinois enacted a law expanding practice authority for certain advanced practice nurses in 2017, and policy makers should examine other health care professions to see whether scope of practice could be expanded more broadly to meet increased need for medical services.

Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker issued an emergency order on interstate licensing reciprocity that he said would allow qualified out-of-state nurses to practice in his state in “one day.” Illinois is currently party to the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact but not the Nurse Licensure Compact. Now is the time to make it as easy as possible for medical professionals to work across state lines, rather than practice economic protectionism.

3) Enact modest pension reforms to ease pressure on the budget and protect retirement systems from insolvency

After shielding workers from job losses and mitigating the spread of COVID-19, the next challenge is minimizing budget deficits.

Illinois’ last best option to quickly save money without negative economic effects is pension reform. A pension reform plan proposed by the Illinois Policy Institute could immediately save the state $2.4 billion in pension contributions to add some cushion to the budget, without taking away a dollar earned to date by public workers. While a necessary constitutional amendment would take time to enact, lawmakers could pass the amendment this spring so it is on the ballot in November 2020. They could then change the funding ramp immediately to match what actuarial contributions would be if voters approve reform.

Pension reform would enable the state to reduce deficits and spending without harming vulnerable residents or deepening a potential recession. That’s because payouts from the pension funds themselves would not be reduced, just the contributions the state makes to the funds to cover future obligations, preventing any depressive economic effects cuts can cause.

Pritzker has historically been opposed to pension reform, often citing the opposition of public-sector labor unions. However, as the governor himself said: “There are no easy decisions left to make as we address this unprecedented crisis. Every choice now is hard, and it comes with real consequences for our residents.”

During a crisis, politics should be set aside to do what’s right for state residents. Pension reform is a critical need for Illinois. And failing to tackle this challenge proactively will ultimately result in serious harm for public-sector retirees.

Illinois leaders in the public and private sectors have shown an incredible ability to come together to fight COVID-19’s public health threats, including making politically difficult decisions. With the real threat of a recession looming, they should do the same to fight COVID-19’s threats to public finances.