The problem

Chicago is suffering from one of the worst pension crises in the nation.

To begin fixing its failing system, the city should move away from a politician-controlled, defined-benefit system.

But another important step is reforming retirement-age requirements.

The Chicago systems’ retirement ages don’t reflect today’s fiscal and demographic realities.

People are living longer, which means government-sector retirees are collecting more retirement benefits for longer periods than in the past.

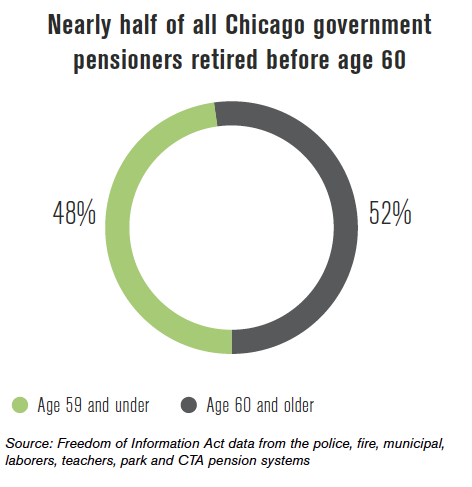

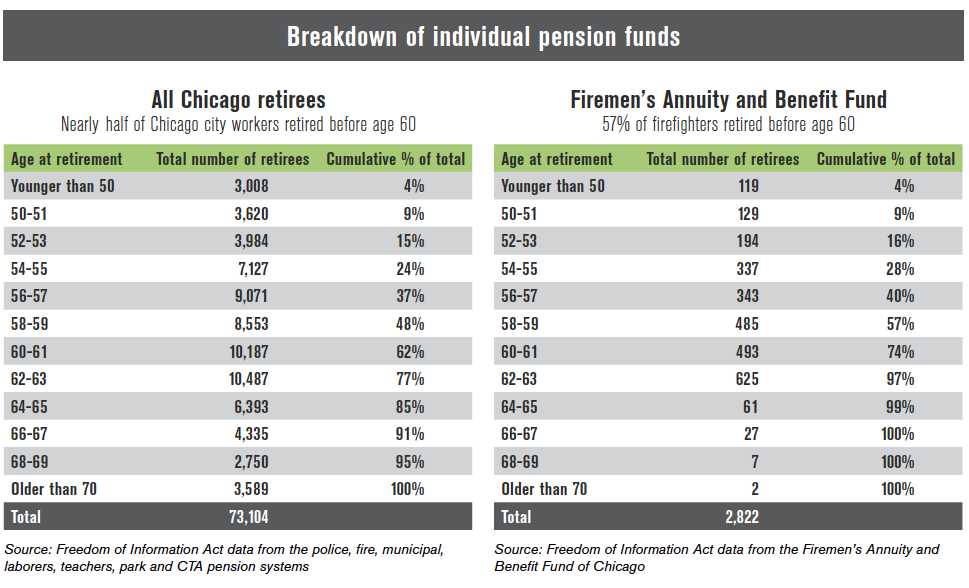

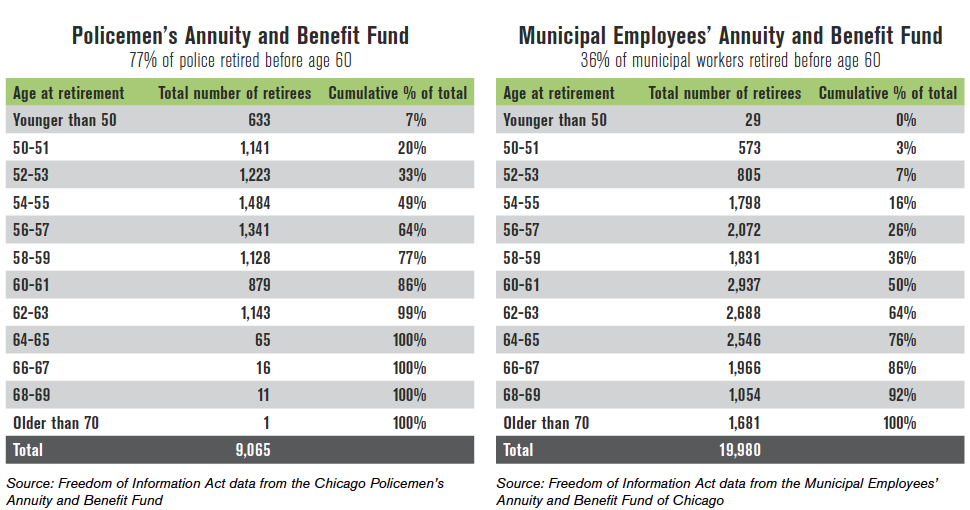

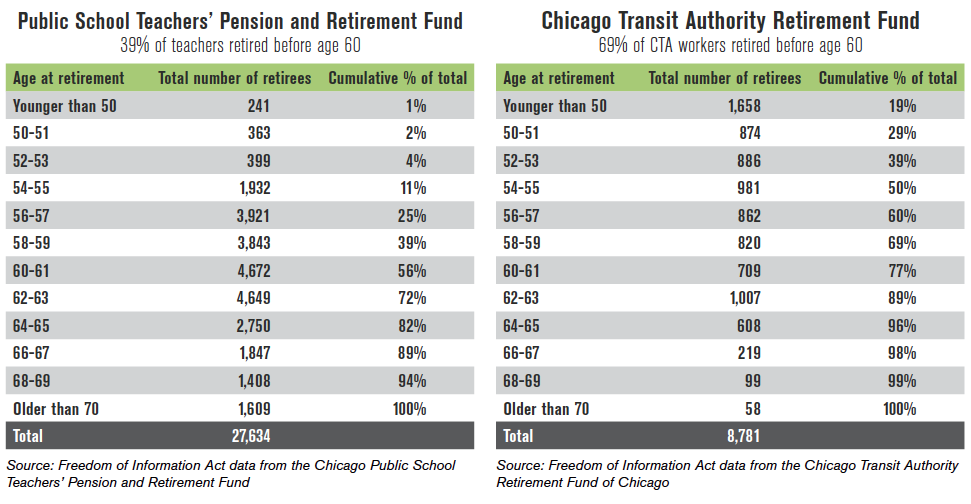

This problem is compounded by the fact that Chicago’s city workers are able to retire in their 50s while collecting a majority of their final average salary. Nearly half of all Chicago government retirees quit working before age 60.

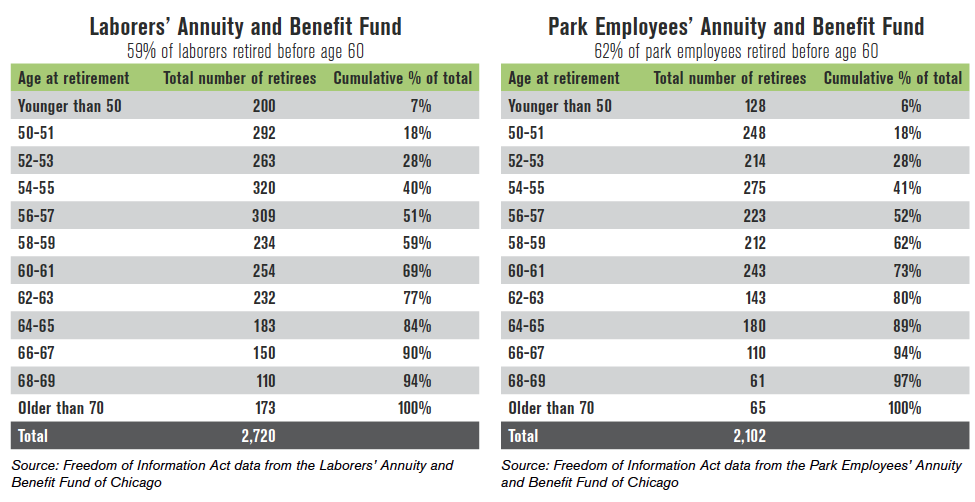

While police and fire employees can understandably be expected to retire at younger ages, other city workers are retiring early as well. Nearly 70 percent of Chicago Transit Authority workers retired before age 60. Another 59 percent of laborers retired in their 50s.

Allowing city workers to retire so early puts a tremendous strain on both city taxpayers and the city’s pension systems that neither group can afford.

City workers who have retired early have done nothing wrong. They made an economic decision that’s fair game under the law. But those benefits are no longer sustainable.

Private-sector retirements ages

Private-sector workers are retiring much later than their public-sector counterparts.

Stung by a weak job market, declining earnings and low home values, older Americans in the private sector have accepted the reality of a retirement that comes later in life and no longer represents a complete exit from the workforce.

According to a recent survey, 40 percent of working Americans age 50 or older say it is at least somewhat likely they will work for pay in retirement.1

And a recent Gallup poll found that the majority of all age groups expect to retire at age 65 or older.2

The solution

The retirement age for city workers should be more closely aligned with private-sector retirement ages going forward.

Any reforms should bring the retirement age of city workers in line with Social Security retirement ages, while making sure not to penalize workers near retirement under current law (due to the nature of their work, Chicago’s police and fire employees would retire at an earlier age).

The Illinois Policy Institute’s comprehensive pension reform plan does just that.

This plan aligns the retirement age for city workers with the private sector. The age at which workers can begin collecting a pension is based on how close workers are to retirement under current law and how many years they’ve dedicated to the city.

The plan protects the retirement ages of longtime employees who are already nearing retirement. The closer employees are to their current legal retirement age, the fewer additional years are added to that retirement age, provided the new age will be no younger than 59. Younger workers will be given more time to plan and budget for changes in the retirement age.

The Institute’s proposal also creates a hybrid retirement plan that gives city workers control over their own retirements.

Going forward, workers would own and control a hybrid retirement plan that contains two key elements: a self managed plan and a Social Security-like benefit. The plan is careful to protect benefits that have already been earned by current workers and retirees under the existing pension plan.

By moving to a hybrid pension plan, retirement costs would become a more stable and predictable portion of city budgets, helping prevent indiscriminate cuts to core government services. And taxpayers would no longer be subject to paying higher taxes to fund ever-growing pension shortfalls.

The Institute’s plan is the only fair and affordable proposal to both guarantee a secure retirement for city workers and retirees, and ultimately solve the city’s pension crisis.