Executive Summary

Over the past several decades, Illinois’ prison population has exploded. Between 1984 and 2014, inmate population increased by roughly 182 percent, while the state population only grew by 12 percent over the same time period.

This rapid increase in the prison population has come with numerous costs for the state: increased prison budgets, growth in the number of people cycling in and out of prison, wasted human capital and overall strain on a system that has become too big to manage.

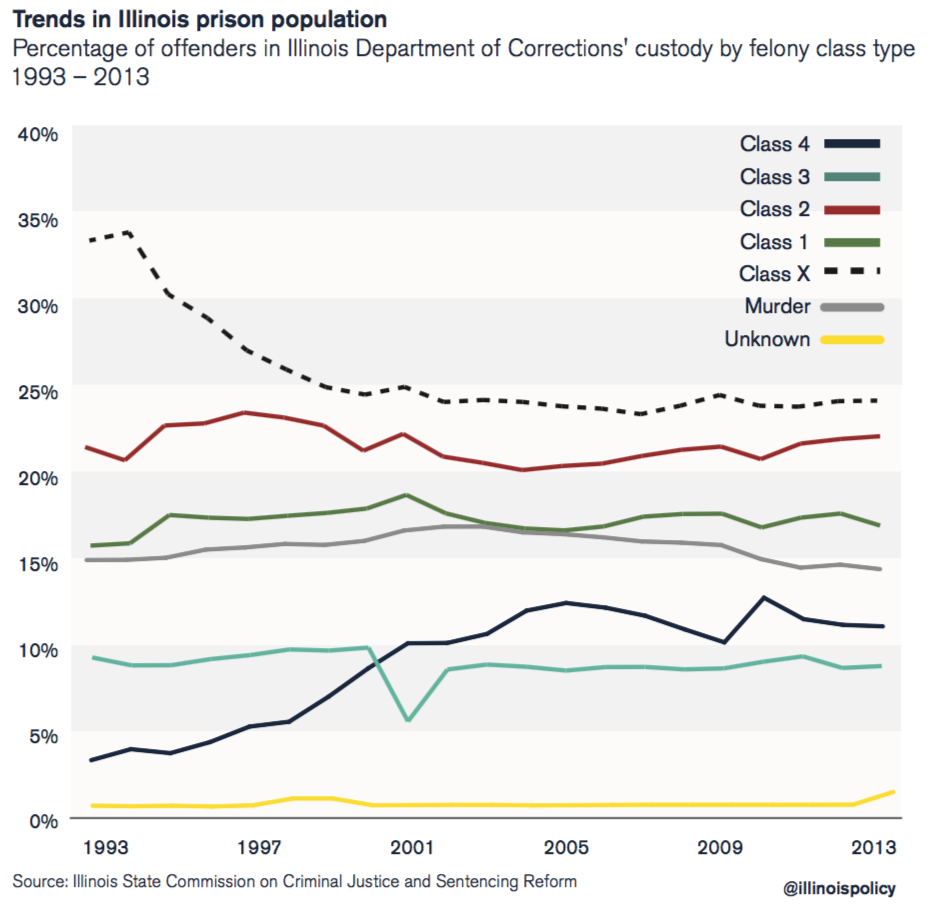

One major first step in reversing this cycle is revising Illinois’ draconian sentencing rules for low-level, nonviolent drug possession and theft crimes. People convicted of these types of crimes, or Class 4 felonies, are the biggest driver behind Illinois’ prison population growth. Between 1989 and 2014, 55 percent of the increase in prison admissions was due to more individuals convicted of Class 4 felonies. Today, Class 4 felony offenders make up the largest sector of incoming inmates in Illinois, accounting for over 37.7 percent of all admissions. The percentage of inmates incarcerated for Class 4 felonies has shot up faster than any other felony class – these inmates made up 11.9 percent of Illinois’ prison population as of 2013, compared with 4.1 percent in 1993.

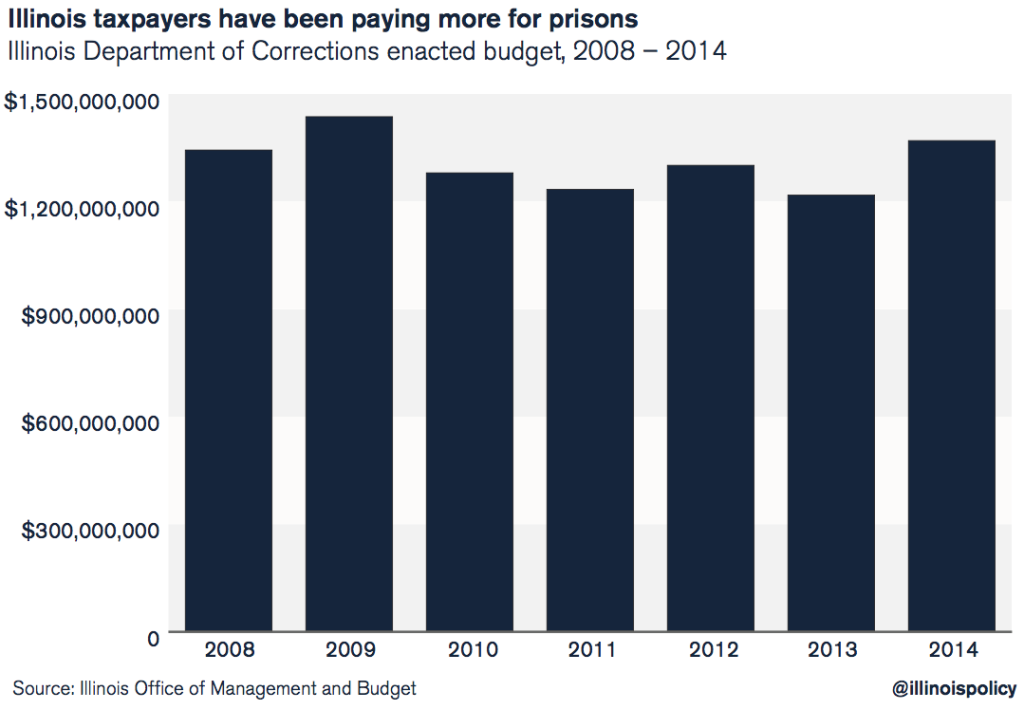

Illinois prisons are among the most overcrowded in the nation, which is dangerous for both inmates and staff. In 2014, the average cost of incarcerating each inmate per year in Illinois was $21,071, and the cost of maintaining the system ballooned to almost $1.4 billion per year. This figure does not include additional outside costs taxpayers bear, such as administrative costs, pension contributions, employee benefits and taxes, retiree health care contributions, and capital costs.

To address these problems, in February 2015, Gov. Bruce Rauner created a criminal-justice task force to identify areas of the criminal-justice system that could be reformed that would result in a 25 percent reduction in the prison population by 2025 – an ambitious task.

The best way to start would be to change how the state responds to low-level, nonviolent drug and property felonies – a modest yet necessary first step in making broader reforms.

In addition to being overcrowded and expensive for taxpayers to maintain, the Illinois Department of Corrections system does not have a successful rehabilitative track record, as nearly half of all prisoners released each year – 48 percent – recidivate, or are convicted of a new crime, within three years of release.

There’s little evidence that requiring low-level offenders to serve lengthy prison terms produces positive results for public safety. Across the country, many states have reduced their prison populations and violent crime rates simultaneously. Several of these states saw reductions in their prison populations and violent crime rates as a direct result of comprehensive sentencing reforms.

With Rauner’s goal in mind, this report recommends making several changes to the way Class 4 felony offenders are sentenced:

- Decriminalizing the possession of small amounts of controlled substances for personal use.

- If decriminalization isn’t adopted, Illinois should at least create a threshold necessary to trigger felony drug possession, effectively making possession of certain controlled substances below that threshold a Class A misdemeanor offense. Several states across the country have done this, and seen positive results in terms of public safety and taxpayer savings. Indeed, South Carolina has seen its prison population decrease by nearly 12 percent and its violent crime rate decrease by over 25 percent in just four years after reforms were enacted. Since the reforms were enacted, the state has also saved over $18 million.

- Illinois should increase the threshold necessary to trigger a Class 4 felony retail theft offense from the current $300, and the threshold necessary to trigger a Class 3 felony theft offense from the current $500. Many other states’ thresholds are twice or four times as high as Illinois’. Wisconsin has a $2,500 felony theft threshold, and the rate of theft in the state is similar to Illinois’, which shows this reform would not necessarily lead to an increase in theft in the state, but instead allow individuals who commit low-level offenses to be punished more proportionately.

This brief shows that reforming the state’s lowest-level nonviolent drug and property felonies is a modest yet necessary first step in making broader reform – and in meeting the governor’s 25 percent reduction goal – an eventual reality.

Introduction

One of the biggest drivers of Illinois’ prison population is the growth in the number of low- level, nonviolent offenders the state incarcerates. Between 1989 and 2014, 55 percent of the increase in prison admissions was due to more individuals convicted of Class 4 felonies, with a large number of these offenders having been convicted of low-level offenses such as drug possession, low-level retail theft, and driving with a revoked license. Today, Class 4 felony offenders make up the largest sector of incoming inmates in Illinois, accounting for over 37.7 percent of all admissions.

Illinois prisons are among the most overcrowded in the nation, which is dangerous for both inmates and staff. In 2014, the average cost of incarcerating each inmate per year in Illinois was $22,191, and the cost of maintaining the system ballooned to over $1.37 billion per year. This figure does not include additional outside costs taxpayers bear, such as administrative costs, pension contributions, employee benefits and taxes, retiree health care contributions, and capital costs.

In addition to being overcrowded and expensive for taxpayers to maintain, the Illinois Department of Corrections system does not have a successful rehabilitative track record, as nearly half of all prisoners released each year – 48 percent – recidivate, or are convicted of a new crime, within three years of release.

There’s little evidence that requiring low-level offenders to serve lengthy prison terms produces positive results for public safety. Indeed, many states across the country have reduced their prison populations and violent crime rates simultaneously.

Illinois, however, saw its prison population increase by roughly 7 percent from 2009 to 2014, despite the fact that its violent crime rate dropped roughly 26 percent during that same time period.6 Today, Illinois’ prison population is unsustainable: The state’s prisons are overcrowded, the cost of maintaining the system significantly burdens taxpayers, recidivism rates are nearly 50 percent, and low-level, nonviolent offenders continually cycle through the system, producing limited to no benefit to public safety.

This report examines the driving factors behind Illinois’ prison population growth, contextualizes corrections system costs, and offers practical solutions to curb the number of low-level, Class 4 felony offenders continually cycling through the Illinois prison system every year – all while ensuring public safety is protected.

Prison population

Over the past three decades, Illinois’ prison population has grown significantly. Between 1984 and 2014, the state prison population grew to 48,278 in 2014 (roughly 0.37 percent of Illinois’ general population) from 17,114 inmates in 1984 (roughly 0.15 percent of Illinois’ general population), which represents a roughly 182 percent increase in the number of inmates.

In fact, growth in Illinois’ prison population far outpaced the growth of the state’s general population. Although Illinois’ prison population increased by roughly 182 percent between 1984 and 2014, its general population only increased by 12.9 percent, to 12.88 million from approximately 11.41 million.

The growth of Illinois’ prison population is expected to continue. According to the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council, the prison population is estimated to increase by over 7,100 inmates over the next 10 years, eventually reaching 55,450 by 2025.

Overcrowding

As a result of the rapid influx of additional inmates over the years, Illinois’ prisons are dangerously overcrowded today. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, Illinois’ prisons were operating at roughly 150.4 percent of operational capacity on average, and 171.1 percent of design capacity at the end of 2014.10 The Bureau of Justice Statistics defines operational capacity as “the number of inmates that can be accommodated based on a facility’s staff, existing programs, and services,” and design capacity as “the number of inmates that planners or architects intended for the facility.”

Out of all states measured, Illinois had the most overcrowded prisons in the nation when it comes to operational capacity, and the second most overcrowded prisons (behind Alabama) when it comes to design capacity alone by the end of 2014.

Additionally, due to Illinois’ financial insolvency, including a $111 billion unfunded pension liability, spending millions to construct and operate additional prisons to accommodate the growing number of prisoners is not a feasible solution to the overcrowding problem.

Cost

With the rising prison population comes rising corrections costs, and Illinois taxpayers are left to bear the financial burden. In 2014, it cost an average of $22,191 to incarcerate one inmate in an Illinois prison for one year, or roughly $1.08 billion to incarcerate the total prison population in that year alone.14 That same year, the enacted budget for the Illinois Department of Corrections was approximately $1.37 billion, an increase of roughly $152 million from 2013.

However, the real cost of the corrections system to taxpayers is estimated to be much higher than this $1.37 billion figure. According to the Vera Institute of Justice, 32.5 percent of the costs of the state corrections system are outside of the corrections budget, the second-highest percentage of costs outside of the corrections budget of any state in the country, just below Connecticut.

While the Illinois Department of Corrections, or IDOC, budget accounts for inmates housed in IDOC facilities and other operational expenditures, additional costs such as administrative costs, pension contributions, employee benefits and taxes, retiree health care contributions, and capital costs are not included, and are allocated from elsewhere. With these additional costs in mind, the actual price of incarcerating each inmate per year is much higher for Illinois taxpayers. According to a Vera Institute analysis, the actual cost of incarcerating each inmate per year, with these additional costs figured in, was roughly, $38,268 in the 2010 fiscal year.

High costs, low returns

In addition to being overcrowded and expensive for taxpayers to maintain, the IDOC system does not have a successful rehabilitative track record. Indeed, nearly half of all prisoners released each year – 48 percent – recidivate within three years of release. According to a 2015 report published by the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council, the average cost associated with one formerly incarcerated person recidivating is $118,746. The report predicts that recidivism will cost the state of Illinois roughly $16.7 billion between 2015 and 2020.

Explosion in Class 4 felony admissions

Felony classifications in Illinois: Overview

Each crime carries a different felony class status in Illinois, ranging from Class 4, the lowest and least-serious felony classification, to Class X, the highest and most serious felony classification just below murder, which is the only offense that falls outside of this felony class structure.

Sentences prescribed for a Class 4 felony conviction range from between one and three years, but the actual time served by those convicted of Class 4 felony offenses is 0.64 years on average, or a little more than seven months. Some examples of Class 4 felonies are possession of any amount of certain controlled substances, retail theft and driving with a revoked license.

Class 4 felony admissions to prison

According to the first report issued by the Illinois State Commission on Criminal Justice and Sentencing Reform, 55 percent of the increase in prison admissions between 1989 and 2014 was due to increased admissions of individuals convicted of Class 4 felonies, with a large number of these individuals having been convicted of drug offenses, such as drug possession.

Indeed, the largest percentage of inmates admitted to prison in Illinois were convicted of a Class 4 felony offense, and the percentage of admissions for Class 4 felony offenses skyrocketed after 1999. In 2013, roughly 37.7 percent of all inmates admitted to prison were convicted of a Class 4 felony offense.

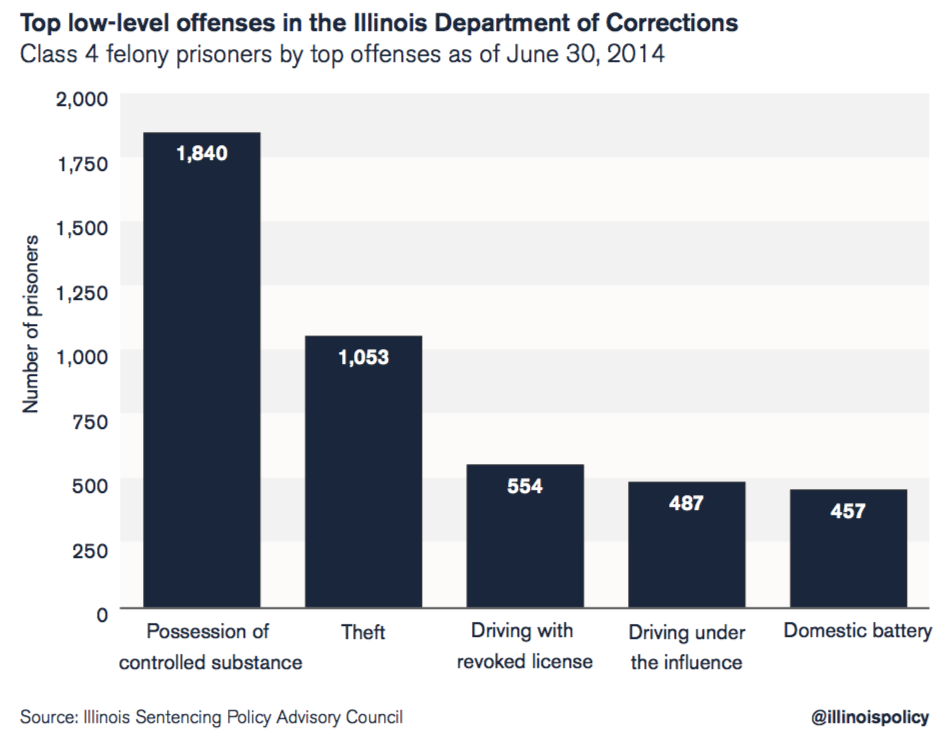

Most offenders serving a sentence for a Class 4 felony offense were convicted of low-level, nonviolent offenses. Most inmates serving a sentence for a Class 4 felony offense were convicted of Class 4 felony possession of a controlled substance, followed by a Class 4 felony theft offense and driving with a revoked license.

High recidivism rate

Because of the relatively short sentences that are served, individuals convicted of Class 4 felony offenses are given little opportunity to engage in rehabilitative programming, or any substance abuse or mental health treatment they may need before they are released back into society. This is problematic, as providing limited access to rehabilitative programming in prison increases the chances inmates will recidivate after release, providing low returns to an already expensive and inefficient corrections system.

Indeed, while the overall three-year recidivism rate in Illinois is roughly 48 percent, according to the Illinois State Commission on Criminal Justice and Sentencing Reform, offenders convicted of a Class 4 felony who are admitted to IDOC have higher recidivism rates and more extensive criminal histories as compared to other offenders. This signals that many of these low-level offenders are continually cycled through Illinois’ criminal-justice system, which is ineffective and expensive for taxpayers.

Class 4 felony drug offenses

Possession of most controlled substances in Illinois is either a Class 1 felony or a Class 4 felony, with the exception of possession of methamphetamine, which ranges from a Class 3 felony to a Class X felony. The duration of incarceration varies according to the amount of the substance involved.

or example, it is a Class 1 felony to possess more than 15 but less than 100 grams of heroin, cocaine or morphine, among other drugs. This offense carries between four and 15 years in prison, depending on the substance. Possession of more than 100 and less than 400 grams of these substances carries a six- to 30-year prison sentence, and increasing amounts carry longer sentences beyond this. However, possession of any amount below 15 grams of certain controlled substances – even a barely detectable amount – is a Class 4 felony offense. Meaning, two individuals convicted of possessing very disparate amounts of these illicit substances could receive the same Class 4 felony sentence for possession. Because there is no threshold necessary to trigger a Class 4 felony drug possession offense, individuals caught possessing even 0.1 gram of such a substance may receive Class 4 felony convictions and subsequent prison sentences.

As of June 30, 2014, 1,841 inmates were serving sentences for Class 4 felony possession of a controlled substance. These inmates represented 32.1 percent of all inmates convicted of a Class 4 felony offense, and therefore the largest category of Class 4 felony inmates.

Methamphetamine

It should be noted that possession of methamphetamine is punished more harshly than possession of most controlled substances in Illinois, and possession of any amount of methamphetamine is at the very least a Class 3 felony. Indeed, possession of less than five grams of methamphetamine is a Class 3 felony, and possession of five to 15 grams of methamphetamine is a Class 2 felony offense. As highlighted above, possession of 15 grams or less of most controlled substances is a Class 4 felony offense.

There is little evidence that requiring tougher sentences for individuals convicted of possessing methamphetamine – as opposed to other drugs – is an effective deterrent, is cost-effective, or provides an added benefit to public safety. Instead, it results in more individuals in prison for longer periods of time, with no added benefit for taxpayers.

Class 4 felony property offenses

In Illinois, the threshold necessary to trigger certain felony theft statutes is very low, and indeed lower than those in many neighboring states. For example, theft of property from a person is a Class 3 felony if the amount involved is $500, and retail theft is a Class 4 felony offense if the amount involved is only $300.

With felony theft, Illinois has two classifications, theft of property not from the person, and theft of property from the person. Theft of property not from the person when the amount is $500 or less is a Class A misdemeanor offense, but is a Class 4 felony offense if the theft was committed in a school, place of worship, was government property, or if the offender has previously been convicted of certain offenses, including any type of theft, burglary, armed robbery, etc.

Theft of property from the person when the amount is between $500 and $10,000 is a Class 3 felony offense under Illinois law. If this theft of property valued at between $500 and $10,000 occurs in a school or place of worship, or if the theft is of government property, it is a Class 2 felony offense in Illinois. It’s important to note that Illinois did increase its felony theft threshold to $500 from $300 in 2010, though it did not benchmark this increase against inflation.

As of June 30, 2014, 23.9 percent of inmates serving a sentence for a Class 3 felony were convicted of a theft offense. This was the top offense of which Class 3 felony offenders were convicted. Similarly, 18.3 percent of all inmates serving a sentence for a Class 4 felony were convicted of a theft offense. This was the second-most frequent offense for which all Class 4 felony offenders were serving sentences, below possession of a controlled substance.

Using 2011 reporting data from Rockford, Ill. – the only Illinois county to submit data to the National Incident-Based Reporting System, or NIBRS, in 2011 – the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council found that most retail thefts committed in Illinois are low in value. In 2011, over 87 percent of all retail thefts in Rockford were for items valued at $500 or less, and over 91 percent of all retail thefts were items valued at below $1,000. Of those thefts of items valued below $500, 5.2 percent were for thefts of items valued between $300 and $500, a Class 4 felony offense in Illinois, while the majority were under $150.

The Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council also examined 2011 property theft value data for Rockford, Ill., from the NIBRS and found that most incidents of theft in the county were low in value as well. In 2011, over two-thirds of all property thefts were of items valued below $500, and 80 percent were of items valued below $1,000.

While the analysis states Rockford numbers are not fully representative of all theft in Illinois, it notes that the numbers match closely the theft statistics in neighboring states.

Many other states have increased their felony theft thresholds in recent years. Since 2001, at least 33 states have increased their felony theft thresholds. Of those 33 states, 27 have increased their thresholds beyond Illinois’ $500 level. Some of these states have a threshold twice or more than four times as high as Illinois’. Such states include Texas ($2,500), South Carolina ($2,000), Alabama ($1,500), Mississippi ($1,000), and Ohio ($1,000), to name just a few.

In neighboring Wisconsin, theft of items valued at $2,500 is the threshold necessary to trigger the lowest-level felony offense for theft and retail theft. Theft of items valued at less than $2,500 is a Class A misdemeanor in Wisconsin.

Despite having much higher thresholds necessary to trigger felony theft offenses, Wisconsin has a slightly lower rate of theft than Illinois. According to the 2014 FBI Crime Statistics report, Illinois’ rate of larceny theft, a term the FBI uses to broadly describe all theft offenses, was 1,552.2 (i.e., 1,552.2 larceny theft crimes for every 100,000 inhabitants), and Wisconsin’s larceny theft crime rate was 1,547.6 (1,547.6 larceny theft crimes for every 100,000 inhabitants). This signals that having higher felony theft thresholds does not necessarily result in higher levels of theft, since Wisconsin experienced a slightly lower rate of theft than Illinois despite having much higher dollar thresholds to trigger felony theft statutes.

Recommendations

In February 2015, Gov. Bruce Rauner created a criminal-justice task force with the hope that it would identify areas of the criminal-justice system that could be reformed to accomplish a 25 percent reduction in the state’s prison population by 2025 – an ambitious task. Reforming sentencing rules for the state’s lowest-level nonviolent drug and property felonies is a modest yet necessary first step in making broader reform – and that 25 percent reduction – an eventual reality.

Reform Class 4 felony drug possession offenses: Raise the threshold

Possession of wildly disparate amounts of controlled substances triggers the same Class 4 felony offense and subsequent prison sentence. An individual convicted of possessing less than one gram of certain controlled substances, and another convicted of possessing 14 grams, or roughly half an ounce, of certain controlled substances may both receive the same Class 4 felony sentences despite disparate amounts of drugs involved.

Instead of continuing to incarcerate individuals for possessing small amounts of illegal substances, Illinois should first consider decriminalizing possession of small amounts of controlled substances for personal use. Decriminalization differs from legalization in that it would not legalize the sale of controlled substances, but rather prevent individuals who possess small amounts of drugs for personal use from receiving criminal records. Decriminalization would allow law enforcement to issue infractions, similar to how traffic laws are enforced.

Decriminalizing the possession of a small amount of controlled substances would significantly reduce the number of individuals cycling through Illinois’ prison system for low-level drug possession. As noted above, most offenders serving Class 4 felony sentences were convicted of possession of a controlled substance. The decriminalization of possession of small amounts of controlled substances would significantly free up space and resources that can be prioritized for those who have committed more serious offenses.

If decriminalizing small amounts of controlled substances for personal use is not politically possible, Illinois should at least consider creating a threshold necessary to trigger felony drug possession, effectively making possession of certain controlled substances below that set threshold a Class A misdemeanor offense. Although less ideal than decriminalization, prescribing misdemeanor sentences for individuals convicted of low-level drug possession offenses gives judges flexibility in sentencing, which could range from probation, to drug treatment, to behavioral therapy, to other rehabilitative programming.

Several states across the country have reformed their felony drug-possession statutes and made low-level drug possession a misdemeanor offense. These changes have occurred in both liberal and conservative states, such as South Carolina, Utah, Connecticut and California.

For example, South Carolina enacted comprehensive sentencing reforms in 2010 with Senate Bill 1154, or the Omnibus Crime Reduction and Sentencing Reform Act. This law made possession of a small amount of certain controlled substances a misdemeanor offense.41 Since then, South Carolina has seen its prison population and violent crime rate decrease simultaneously. Between 2009, the year before the reform was enacted, and 2014, South Carolina’s prison population decreased by 11.89 percent, to 21,401 in 2014 from 24,288 in 2009. During the same time, South Carolina’s violent crime rate decreased by 25.8 percent, to 497.7 violent crimes per 100,000 residents in 2014 from 670.8 violent crimes per 100,000 residents in 2009. Additionally, according to The Pew Charitable Trusts, this reform has allowed the state to close two prison facilities, and has saved the state at least $18.7 million, with additional cost savings from avoided incarceration.

Reducing penalties for possession of a small amount of controlled substances, while less ideal than decriminalizing possession of a small amount of controlled substances, would bring about significant cost savings for Illinois’ taxpayers, while ensnaring fewer low-level offenders in the criminal-justice system, which allows the state to prioritize prison space for those convicted of more serious offenses. All of this can be done without compromising public safety.

Indeed, the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council found that if Illinois were to increase the threshold necessary to trigger a Class 4 felony possession-of-controlled-substances offense, including methamphetamine, to one gram, and require those offenders to serve a term of probation or a misdemeanor jail term, the state would save roughly $57.6 million over three years. furthermore, using 2011 data from the Administrative Office of the Illinois Courts, the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council found that over 5,200 inmates would be diverted from prison to either probation or a misdemeanor jail term if these legislative changes were to be enacted.

Reform Class 4 felony retail theft and Class 3 felony theft statutes: Raise the thresholds

Another commonsense reform Illinois legislators could enact would be to significantly increase the thresholds necessary to trigger a Class 4 felony retail theft and a Class 3 felony theft offense. While the amount can and should be debated among legislators, Illinois should take note of the felony theft statutes of its neighboring state of Wisconsin, which establish a $2,500 threshold necessary to trigger a felony offense, and other states such as Texas, Mississippi, South Carolina and Ohio, which have all raised their felony theft thresholds in recent years.

Despite a much higher threshold to trigger a felony theft offense, Wisconsin has similar rates of theft crimes as Illinois. This signals that having higher felony theft thresholds does not automatically result in higher rates of theft.

If increasing the threshold to $2,500 is not politically possible, at the very least, Illinois should increase the threshold to adjust for inflation – starting from the dates the original amounts were set – and require the General Assembly to re-evaluate this legislation on a biennial basis. This too would effectively make these crimes a Class A misdemeanor offense if the value involved were less than the set amount.

Using data from 2010 to 2012, the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council estimates that if Illinois had increased the threshold for Class 3 felony theft to $1,000 from $500, and increased the Class 4 felony retail theft threshold to $500 from $300, the sentences of roughly 2,000 inmates might have been affected. The inmates whose sentences might have been affected by these changes represented 8 percent of the 13,411 theft convictions, and 5 percent of the 21,574 retail theft convictions during those years. The council notes that it’s difficult to conduct a fiscal analysis of these changes because other factors beyond the value of the property stolen affect the sentence imposed.

These reforms would require that low-level, nonviolent offenders are punished for their actions, but the punishment would be more proportionate to the crime committed. Instead of requiring these offenders to spend time in jail, wasting taxpayer dollars with little added benefit to public safety, these reforms would allow them to work to reimburse victims for the value of the property taken, and ensure that prison space is reserved for those who have committed more serious offenses.

Conclusion

While the reforms recommended in this policy brief are modest, they represent a promising first step in correcting some of Illinois’ draconian sentencing laws by ensuring punishment is more proportionate to the crime committed. Most importantly, these proposed reforms will also be effective in reducing the number of low-level nonviolent inmates in prison, thereby allowing prison space and resources to be used on offenders who pose a larger risk to public safety.

If Illinois is serious about reforming its overcrowded, expensive and inefficient criminal-justice system, it must consider reforming nonviolent Class 4 felony offenses, such as the drug and property offenses highlighted in this brief, first. Doing so would set the state on a path toward eventual broader reforms necessary to meet the goal of reducing the prison population by 25 percent, all while ensuring public safety is protected.