Illinoisans shoulder one of the highest property tax burdens in the nation. The assessment process determines how that burden is distributed among property owners. While property values themselves shouldn’t raise or lower the overall level of property taxes in a given locale, Illinois’ property assessment laws and practices do affect individuals’ property tax bills, and inaccurate or unfair assessments can mean that some homeowners shoulder more of the property tax burden than they should.

To get a glimpse at property tax assessments in some of Illinois’ most populous counties, the Illinois Policy Institute examined data for Cook, DuPage, Lake and St. Clair counties. The Institute then studied the extent to which state assessment laws make the system less fair and more complicated than it should be. Here is what the research shows:

1. Cook County performed worst on measures of assessment accuracy and fairness, but each county studied fell outside accepted standards in some cases.

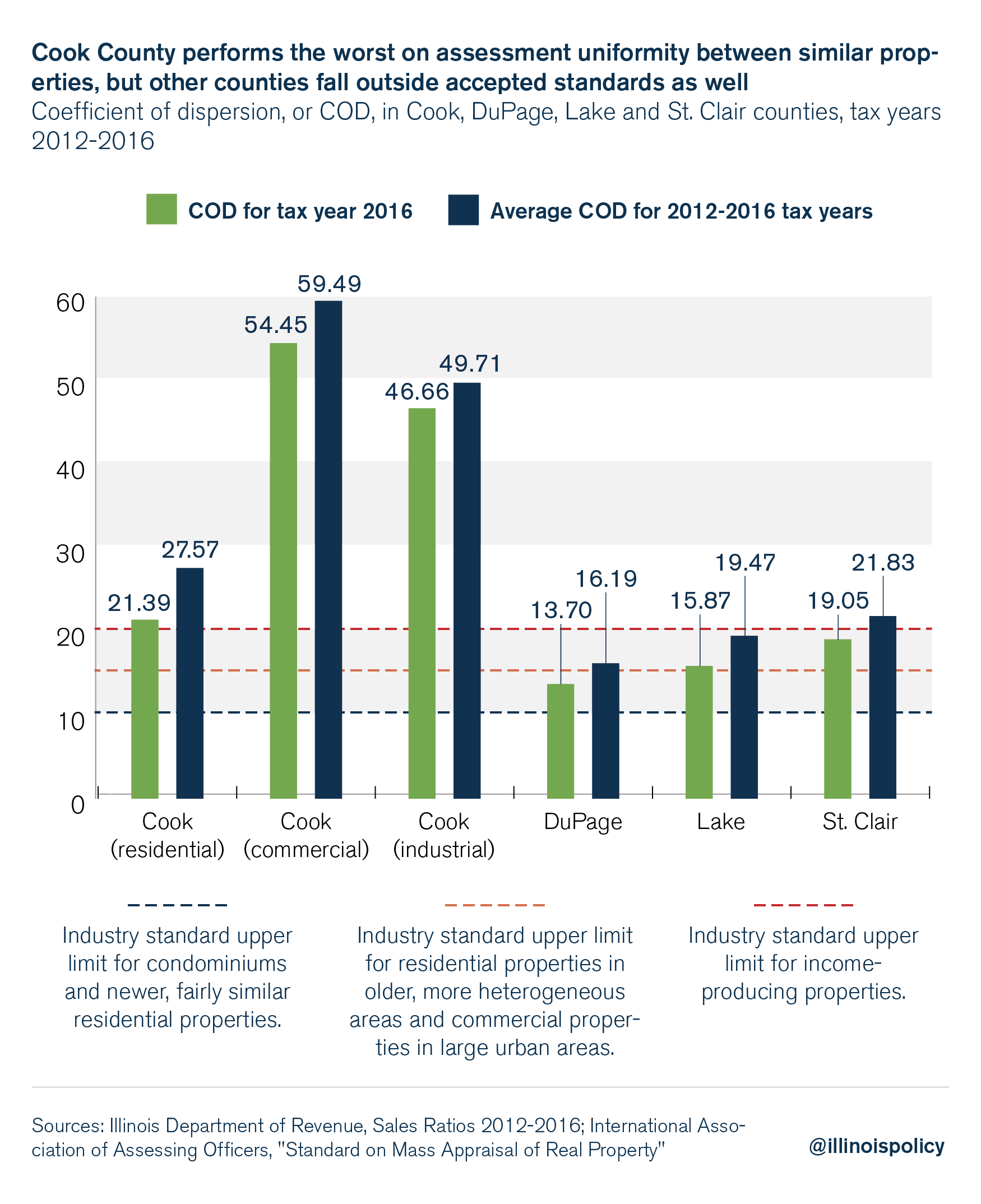

Properties with comparable features located in similar areas should have roughly the same assessed value. Data from the Illinois Department of Revenue, or IDOR, show Cook County performed worst on uniformity of assessments among similar properties, compared with DuPage, Lake and St. Clair counties. All of the counties studied were outside accepted standards in at least some instances, though.

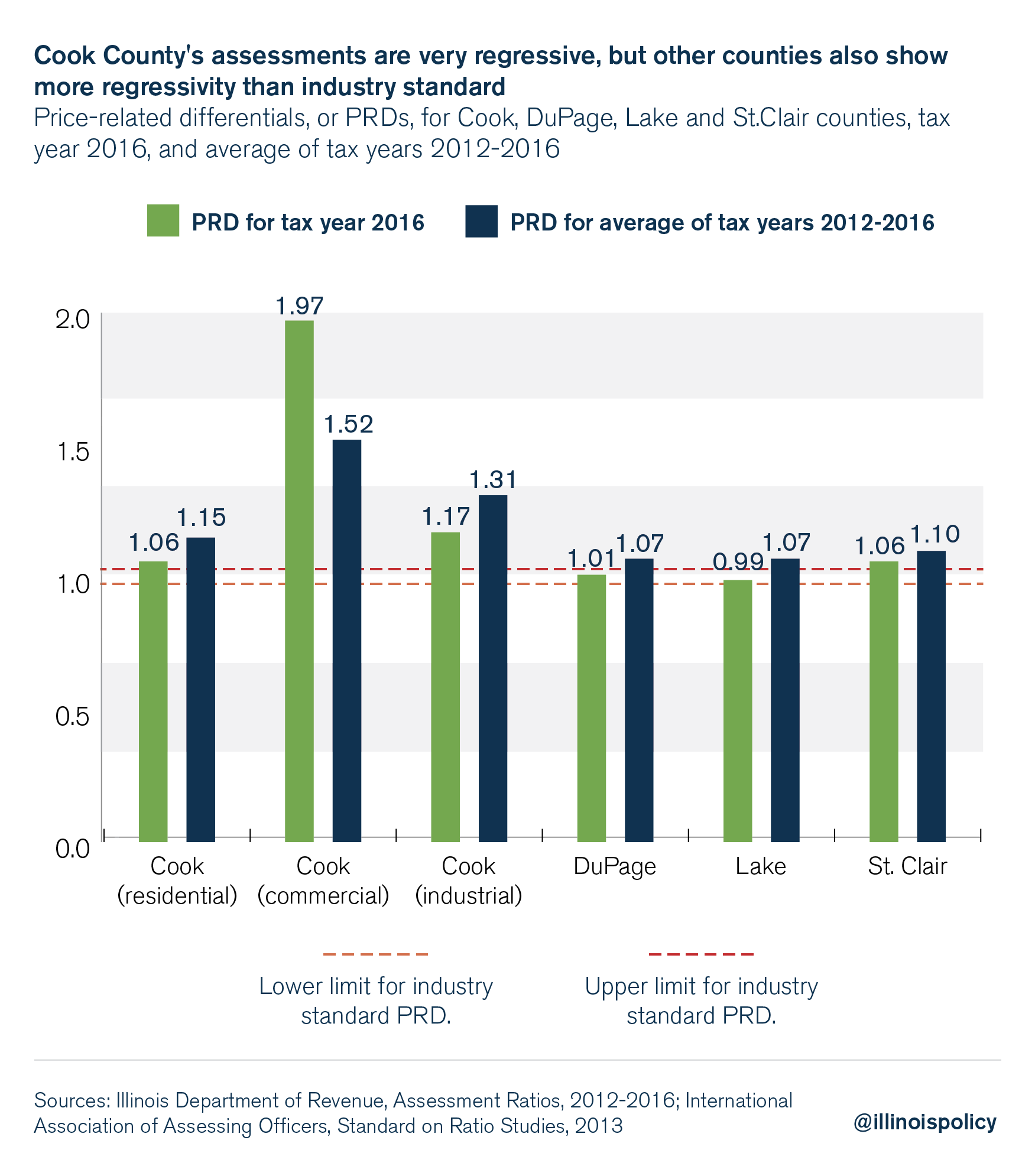

Cook County also showed considerable regressivity in its assessments, according to IDOR information. This means owners of higher-value residential, commercial and industrial property had lower levels of assessed value than owners of less expensive property. In short, wealthier property owners in Cook County tended to catch a break in their assessed values, while poorer property owners did not. The other counties studied also had some instances of regressivity, though not to the extent that Cook County did.

2. Illinois can improve its assessment process by replacing fractional assessment with assessment at full market value.

Illinois law requires property to be assessed at 33 1/3 percent of its market value outside of Cook County; in Cook County, property is assessed at 10 percent and 25 percent of market value for residential and commercial property, respectively. This system of fractional assessments makes it harder for a homeowner to read his or her property tax bill and immediately tell what the assessor thinks the market value is.

Property taxes should be based on the full value of the property, not a fraction of that value. This would eliminate an unnecessary step in the calculation of assessed value, and would make bills easier for taxpayers to read and less likely to obscure overassessment and the effective tax rate.

3. Illinois can improve its assessment process by requiring more frequent assessments and more recent sales data.

In general assessment years, local assessment officials evaluate each parcel of property within a county to determine its fair market value. This happens every four years in all counties outside of Cook County, and every three years in Cook County.

That’s not a good way to operate, considering the fluctuation that can take place in the housing market. Conducting assessments more frequently, such as every year or every other year, would especially benefit taxpayers in times of declining home values, which can’t happen when homes are evaluated every few years.

Additionally, policymakers should reconsider the use of sales data going back three years in the assessment process. Although this might smooth the ascent of assessed values in rapidly rising markets, using the previous three years’ sales data also means that in declining markets, assessed values can be higher than what a homeowner could actually sell his or her property for. Where enough annual sales occur to constitute a representative sample of market data, policymakers should consider whether using only the previous year’s sales data would better serve assessment accuracy and fairness.

4. Targeted relief programs should be limited to homeowners who need help the most.

To the extent that Illinois maintains exemptions from assessed value or other similar relief programs, they should be targeted at property owners who might not otherwise be able to afford their property tax bills. Tailoring exemptions in this way could help struggling Illinoisans while not unduly complicating the property tax system, making it less clear who pays what, or severely distorting the distribution of the burden.

Improving the assessment process, which determines what portion of the tax burden each property owner must shoulder, would result in more accurate, fair and easily understandable property valuations and tax bills – and a more transparent, less complicated and fairer system than Illinois has today.

Introduction

Property taxes are among the most unpopular taxes.1 In Illinois, this anger has recently been fueled by reports of unfair assessment practices, government incompetence and a lack of transparency.2 Taxpayer outrage has spurred a host of campaign promises by Illinois gubernatorial candidates pledging to fix the problem.3

Illinoisans are justified in thinking they have high property taxes.

The median effective tax rate in Illinois, or property taxes paid as a percentage of home value, was 2.29 percent in 2016, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.4 This was close to twice the U.S. median of 1.15 percent5 and the second-highest rate in the nation.6

Moreover, the real burden of property taxes – the share of household income they consume – has grown heavier over the last several years. Property taxes grew six times faster than Illinoisans’ household incomes from 2008 to 2015.7

Illinoisans’ property taxes are high because local taxing bodies in Illinois, such as school districts, spend a lot of money.8 Reducing tax bills will require local governments to keep their spending – and the taxes they demand to cover it – in line with what Illinoisans can afford.

But Illinois’ system also has several features that make the property tax process itself more complicated, less transparent and less fair than it should be.

Recently, the process by which the property tax burden is distributed has come under increasing scrutiny. In Cook County in particular, critics have called attention to the incompetence and corruption behind the egregious variability and unfairness in Cook’s property tax assessments.

The Illinois Policy Institute examined data for assessments – which determine what portion of the tax burden a given property owner must shoulder – in Cook, DuPage, Lake and St. Clair counties. The Institute’s study confirms reports of a lack of uniformity in Cook County’s valuation of similar properties, as well as the relatively heavier burden that Cook County places on owners of lower-valued homes compared with owners of more expensive homes. But Cook County was not alone in failing to meet industry standards for uniformity and fairness: Albeit to a lesser degree, the other counties studied fell short in some instances as well.

This report highlights the overly variable and unjust results of current assessment practices and shows how improving Illinois’ assessment process would result in more accurate, fair and easily understandable property valuations and tax bills for all Illinoisans.

Fairness of assessments: Comparing Cook, DuPage, Lake and St. Clair counties

Cook County performs worst on uniformity of assessments among similar properties, compared with DuPage, Lake and St. Clair counties, although all of the counties studied were outside accepted standards in at least some instances.

As explained in detail in Appendix A, the amount of a property tax bill is determined by two things: the amount of money local governments charge property owners to cover government spending – the levy – and the value of a taxpayer’s property. The levy determines how much taxpayers pay in total, and the property owner’s assessed value determines his or her share of the tab.9

The Illinois Property Tax Code provides for assessment of property at a fraction of fair market value: In Cook County, which uses a classification system, residential property is assessed at 10 percent of fair market value, and commercial and industrial properties are assessed at 25 percent of fair market value. In the rest of Illinois, nonfarm property is assessed at 331/3 percent of its fair market value.10

In general assessment years, local assessment officials review, inspect and evaluate each parcel of property within a county to determine its fair market value. This happens every four years in all counties outside of Cook,11 and every three years in Cook County.12

Industry standards hold that similar properties should be assessed at similar levels, so owners do not unfairly bear disproportionate shares of the property tax burden.13 For example, if two homes in Chicago would each sell for $100,000, they should both be assessed at $10,000, which is 10 percent of the fair market value in accordance with Cook’s classification system. If the Cook County Assessor’s Office assesses one property at $8,000 and the other at $12,000, there is a uniformity problem, and the second homeowner will have a higher property tax bill than the first homeowner.

Assessment officials use the coefficient of dispersion, or COD, as a chief measure of the uniformity of assessments among similar properties.14 The COD measures the variation of individual assessment ratios around the median level of assessments and gauges the degree to which assessments cluster near the median.15 Assessment industry norms provide that a COD of 5 to 10 is the acceptable range for newer or more similar homes, and a COD of 5 to 15 is an acceptable range in areas that are older or have more varied types of properties.16 Similarly, the COD should be between 5 and 20 for income-producing properties, or between 5 and 15 if those properties are in larger, urban market areas.17 CODs above these ranges indicate assessors are valuing similar properties at different levels.

The Illinois Policy Institute examined Cook, DuPage, Lake and St. Clair counties to see how different counties perform on assessment fairness according to metrics reported by the Illinois Department of Revenue, or IDOR. Among the four counties examined for this report, Cook performed the worst on assessment uniformity, according to assessment ratio tables compiled by IDOR.18 DuPage had the most uniform assessments.

In 2016, Cook County had a countywide COD for residential property that was almost 43 percent above the acceptable upper level for an older area with a more diverse housing stock.19 And Cook County’s commercial and industrial assessments varied even more drastically. The countywide COD for commercial properties for 2016 was more than 260 percent higher than the upper range for income-producing properties in larger, urban areas.20 The countywide COD for industrial properties was 211 percent higher than the industry standard.21 These 2016 numbers were significantly better than the average for the five-year period from 2012 through 2016.

Behind the countywide numbers for Cook are CODs that varied widely among the townships within the county. For example, in 2016, the COD for residential assessments in the Hyde Park area of Chicago was 143 percent above the industry upper limit, while the COD for residential assessments was 8 percent below the upper limit in the North Chicago assessment township, which includes the Near North Side parts of the Lincoln Park neighborhood.22 The northern suburb of Barrington had a COD for residential properties that was 35 percent higher than the upper limit, while the south suburban town of Thornton had a COD that was 138 percent above the upper limit.23

CODs for other counties – which lack Cook’s assessment classifications – are for both residential and commercial properties combined. As demonstrated by the following graphic, these counties all performed significantly better than Cook, and DuPage had the most uniform assessments, as measured by the COD.

While the numbers show their assessments are more uniform than Cook’s, every county studied had a five-year average outside the accepted standard.24 Lake also had a COD slightly above the norm for 2016, and St. Clair’s COD was about 27 percent higher than the norm for 2016.

Cook County performs the worst on equity between low- and high-value properties

The price-related differential, or PRD, measures the pattern of inequity in assessments that has a correlation with the value of the property.25 This shows the degree to which higher-value properties are assessed at a lower level than lower-value properties, or lower-value properties are assessed at lower levels than high-value properties.26 The Illinois Department of Revenue, along with the International Association of Assessing Officers, or IAAO, considers a PRD of more than 1.03 indicative of regressive assessments and a PRD of less than 0.98 indicative of progressive assessments.27 From a standpoint of assessment accuracy, neither regressivity nor progressivity is desirable.

Cook County showed considerable regressivity in its assessments, according to the PRD metric. This means owners of higher-value residential, commercial and industrial property had lower levels of assessed value than owners of less expensive property. In short, wealthier property owners tended to catch a break in their assessed values, while poorer property owners did not. Neither DuPage nor Lake showed regressivity in 2016, as measured by PRDs, while St. Clair’s PRD showed some regressivity. The 2012-2016 averages for all counties demonstrated regressivity.28

Illinois Department of Revenue data support other findings of unfair assessments in Cook County

The data from IDOR’s assessment ratios come as no surprise, as Cook County has drawn much criticism for the lack of uniformity in its assessments and the regressivity the system has fostered. Reports have also noted the booming business that has flowed to property tax appeals lawyers – who have donated heavily to Cook County Assessor Joseph Berrios’ political campaigns – as a result of Cook’s faulty assessment system.29

The Chicago Tribune in 2017 released a series of reports that showed how for years the Cook County Assessor’s Office assessed homes and business property in less affluent areas of the county more highly relative to actual market values than it assessed properties in wealthier areas.30 The result is that lower-income property owners pay a higher percentage of their properties’ value in taxes than do owners of more expensive properties.31 A study by the Civic Consulting Alliance commissioned by Cook County in the wake of the Tribune’s reporting confirmed the regressivity and lack of uniformity in the system.32 And in March 2018, a study by University of Chicago researchers quantified the effects of the Cook County Assessor’s Office’s underassessment of higher-value properties: The report noted that in Chicago, $800 million of the property tax burden had shifted to poorer homeowners from owners of properties in the top 10 percent of sale prices.33

The Tribune investigation noted that some of the problems with the assessment process stemmed from using an outdated mainframe computer from the 1990s and failing to implement a more accurate computer assisted mass appraisal, or CAMA, system.34 Moreover, assessment officials adjusted results by hand on a case-by-case basis and did not conduct sales ratio studies of their work on a neighborhood basis to gauge its accuracy and uniformity.35

The Civic Consulting Alliance recommended the assessor conduct and publish sales ratio studies throughout the assessment process, which would reveal the accuracy and uniformity of the assessor’s work as it is completed.36

By contrast, DuPage County notes that its supervisor of assessments conducts yearly sales ratio studies to ensure the different townships within the county are at the proper level of assessment compared with actual sales in the area.37 Lake County also performs regular sales ratio studies for this purpose.38 Personnel in the St. Clair County Assessor’s Office said the board of review examines sales data each year as part of the equalization process.39 The Illinois Policy Institute could not determine whether the St. Clair County Assessor’s Office itself also monitors its assessment accuracy by conducting its own annual sales ratio studies.

A closer look at the assessment process

Some of the problems outlined above are exacerbated by certain features of Illinois’ assessment system. The following is a description of the processes by which property values are determined for tax purposes.

Determining market value

In Illinois, the assessed value is supposed to be based on market value, which the Illinois Department of Revenue defines as the amount at which property would sell in a competitive, open market with a knowledgeable buyer and seller using sound judgment, allowing a sufficient time for a sale, which is not affected by pressures such as foreclosure or bankruptcy.40

To arrive at market value, assessment officials use different valuation approaches depending on the kind of property they are assessing. For residential property, assessors generally use a combination of cost analysis and market value approaches.41 Cost analysis means an assessor will value the land a house is on and add what it would cost to build the house. Then the assessor will subtract an amount for depreciation of the property.42 The assessor also uses market data going back three years for the house and similar properties in the neighborhood to adjust the numbers arrived at through the cost estimate to comport with the actual sales prices of similar houses in the area.43 Assessors rely on computer-assisted mass appraisal, or CAMA programs in the property valuation process.44

For commercial properties, assessors often examine the income the owner derives from the property to arrive at a value for property tax purposes.45

Property classification and fractional assessment

State law sets forth Illinois’ scheme of property valuation. The Illinois Constitution allows counties with over 200,000 residents to establish a classification system for taxing different kinds of real property and gives the General Assembly the right to establish how property will be valued.46 Only Cook County uses a classification system47 – it has 13 different classes of property.48 Cook’s property classification system is structured to impose a lesser share of the property tax burden on homeowners than on owners of office buildings or factories and to provide incentives to property owners to engage in activities such as preserving historically significant structures and building commercial or industrial properties in economically depressed areas. In Cook County, residential property is assessed at 10 percent of fair market value, and commercial and industrial property is assessed at 25 percent of fair market value.49

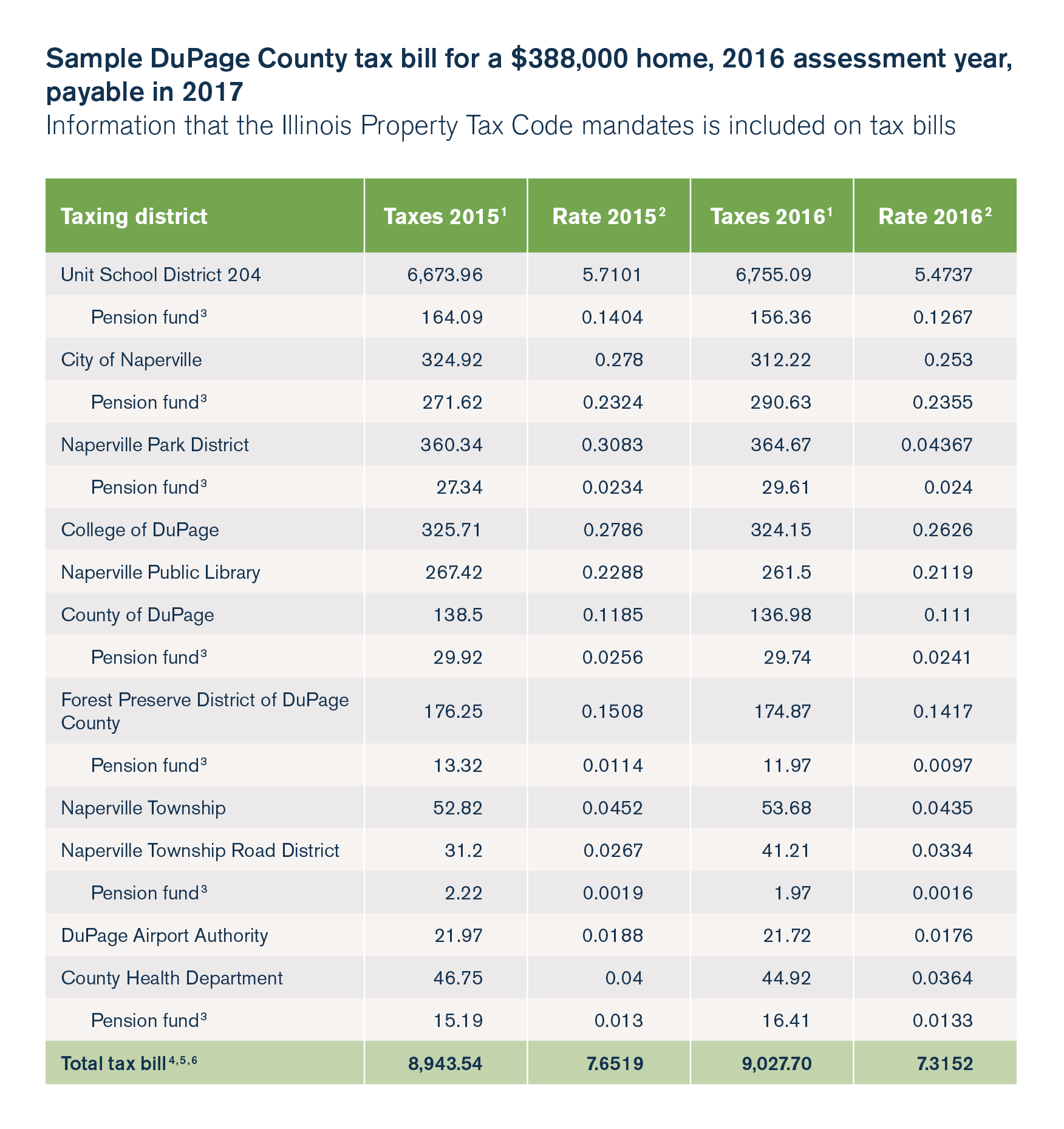

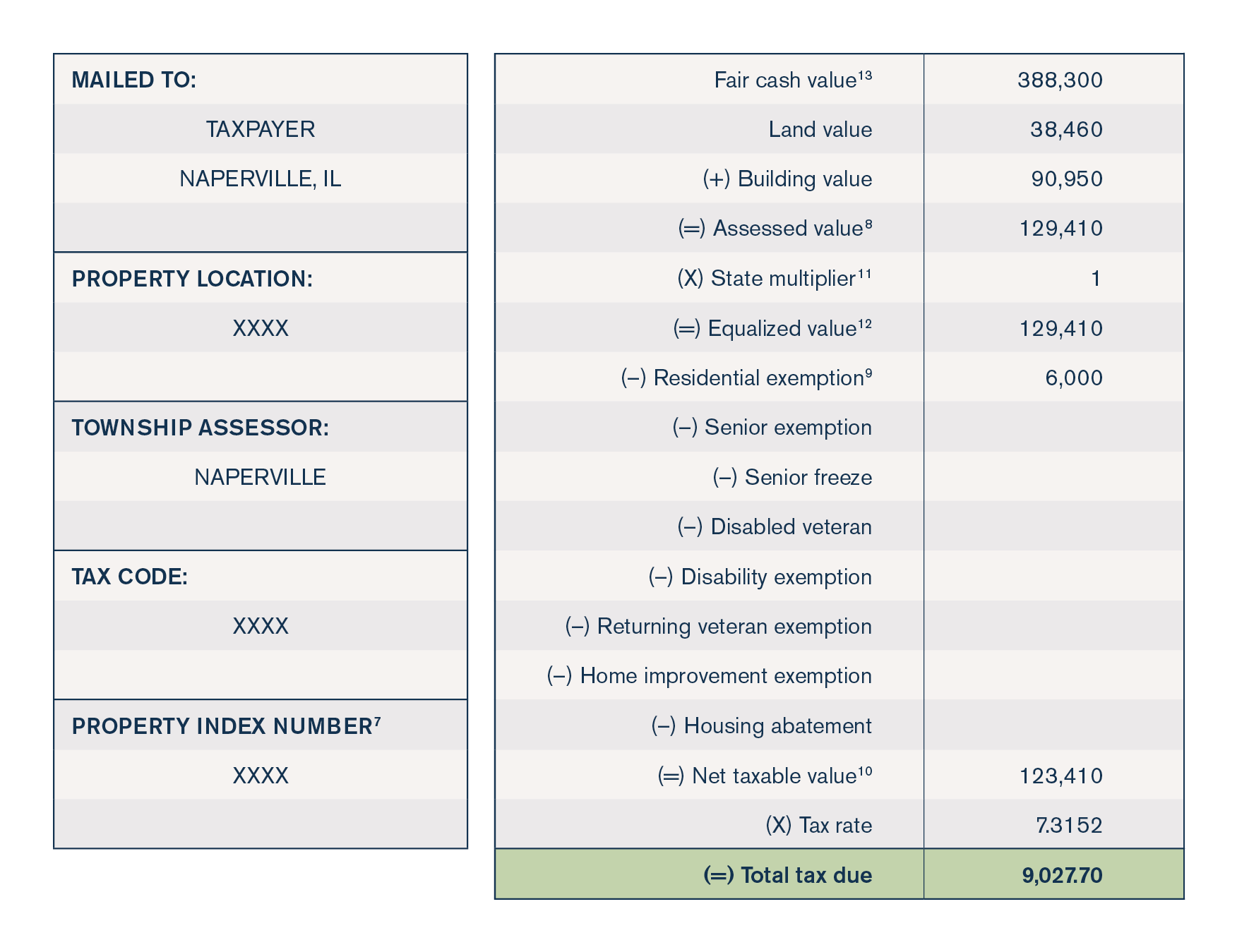

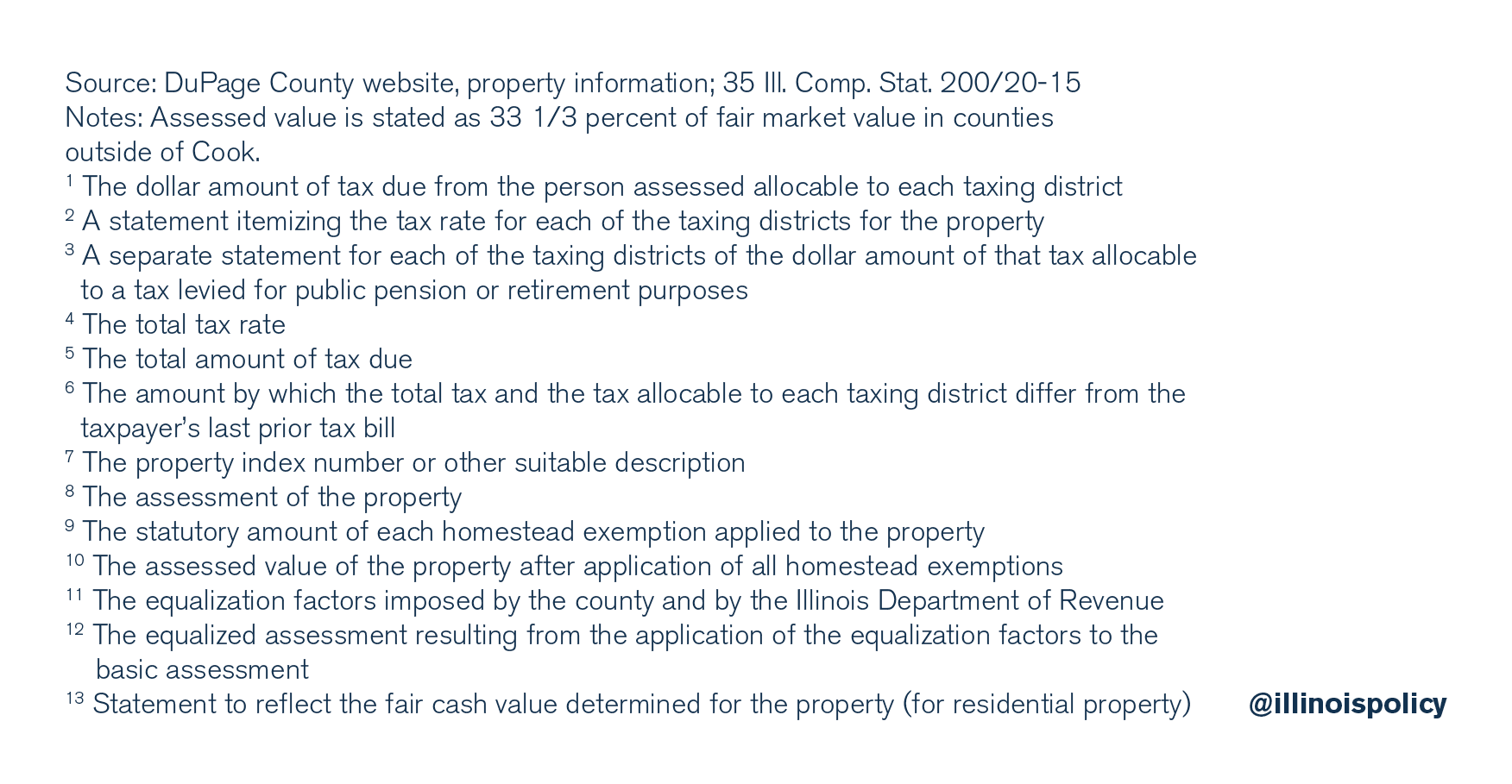

The Illinois Property Tax Code requires counties that do not use classification systems to value nonfarm property at 33 1/3 percent of its fair market value.50 This is called fractional assessment and is authorized by statute in a number of states.51 In many cases, official fractional assessment has replaced a de facto system in which assessors were informally valuing certain kinds of property at a fraction of the full market value.52 The following graphic shows the fractional assessed value on a sample property tax bill.

How Illinois can improve its assessment process

1) Replace fractional assessment with assessment at full market value

In addition to having lower-performing counties such as Cook improve the quality of assessments by implementing high-quality CAMA systems and conducting sales ratio studies on an ongoing basis to monitor uniformity, Illinois should address other factors that make assessment and property tax bills less accurate and less transparent than they should be.

First, the fractional assessment system makes it harder for a homeowner to read his or her property tax bill and immediately tell what the assessor thinks the market value is. At first glance, assessed value stated as 10 percent or 33 1/3 percent of market value can make the assessor’s estimate appear low. Some observers have wondered whether this opaqueness might be viewed by taxing districts as a feature, not a bug, of fractional assessment.53

Moreover, applying fractional assessment requires one more step in the assessment process where errors can potentially be introduced. The state assessor of Maine once described it as “an unnecessary step in the assessment process whereby the full value which must first be found is factored back to produce the fractional assessment to be used.”54 The assessor went on to characterize fractional assessment as a “very real hindrance to true equalization of assessments.”55

According to the International Association of Assessing Officers, or IAAO, “[n]umerous studies indicate that appraisal equity, as measured by such indicators as the … COD, improves significantly when governments eschew fractional assessments and classification schemes for full market value.”56

Significantly, “classification obscures the effective tax rate … [as] the assessment fraction … for the class must be multiplied by the nominal tax rate to determine the effective tax rate.”57 The IAAO concluded: “This step increases confusion and reduces understandability.”58 Scholars have pointed out that fractional assessment can breed “secretiveness” in the tax system, obscuring politically motivated errors, as well as those stemming from incompetence and corruption.59

Other authors have observed that literature on the matter shows fractional assessment can make uneven or unfair assessments harder for property owners to discern.60 This especially hurts property owners with the fewest resources of time and money to pore over and challenge their property tax bills.

Requiring assessment at full fair market value, as Virginia,61 Wisconsin62 and Massachusetts63 do, would eliminate an unnecessary step in the calculation of assessed value and would make bills easier for taxpayers to read and less likely to mask overassessment and the effective tax rate.

2) Require more frequent assessments and more recent sales data

Illinois could improve the accuracy of its assessments by conducting general appraisals more often than every four years or every three years. This would especially benefit taxpayers in times of declining home values, which are not quickly reflected in quadrennial or triennial assessments. The IAAO has observed, “The longer the period between reappraisals, and the more rapidly market conditions are changing, the greater the inequity and the larger the potential magnitude of changes in appraised value.”64 During the Great Recession, property taxes nationwide peaked in 2009, two years after housing prices began to fall.65 To the extent infrequent reassessments cause or exacerbate phenomena such as this, more frequent assessment would improve the situation.

The IAAO has noted that a current market value standard implies the annual assessment of property.66 Accordingly, each year assessors should at least analyze the factors that affect value and use mass appraisal techniques to estimate property values. Assessed values might not necessarily change each year, but assessment officials should monitor the elements that influence them to make sure assessments reflect current market value.67 Cook County’s failure to perform ongoing sales ratio studies or otherwise effectively monitor assessment accuracy flies in the face of this advice.

Illinois lawmakers in consultation with local assessment officials should consider whether annual assessments could be implemented in Illinois, as is the case in Michigan.68 If this is not feasible or if it is too burdensome for local assessment officials, then Illinois could consider conducting general assessments every other year, as Missouri69 and Iowa70 do. Moreover, policymakers should ensure that all localities – including Cook County – measure the accuracy of their assessments through meaningful and effective mechanisms such as properly conducted sales ratio studies.

In addition, policymakers should reconsider the use of sales data going back three years in the assessment process. Although this might smooth the ascent of assessed values in rapidly rising markets, using the previous three years’ sales data also means that in declining markets, assessed values can be higher than what a homeowner could actually sell his or her property for.71 Where enough annual sales occur to constitute a representative sample of market data, policymakers should consider whether using only the previous year’s sales data would better serve assessment accuracy and fairness.72

3) Targeted relief programs should be limited to homeowners who need help the most

Appendix B provides an explanation of Illinois’ property tax exemptions and relief and incentive programs. To the extent that Illinois maintains exemptions from assessed value or other similar relief programs – as opposed to restrictions on levies or rates imposed on local governments – they should be targeted at property owners who might not otherwise be able to afford their property tax bills. Tailoring exemptions in this way could help struggling Illinoisans while not unduly complicating the property tax system, making it less clear who pays what, or severely distorting the distribution of the burden.73

Conclusion

Illinois should take steps toward more accurate and frequent property assessments to ensure the tax burden is distributed as fairly as possible. More accurate, equal and fair assessments can diminish cases in which neighbors with similar homes pay different taxes, and prevent the poor from bearing a disproportionate share of the tax burden, while wealthier homeowners benefit from lighter assessment levels. Limiting relief programs to homeowners who especially need help can also play a role in creating a fairer system.

Unfortunately, improving the assessment process alone will not protect taxpayers from high bills. Illinois needs effective limits on local government spending – which gives rise to high tax levies and rates – to bring property taxes down. Although Illinois has some property tax limitations such as the Property Tax Extension Limitation Law, these have not sufficed to keep the growth in property taxes from outpacing increases in personal income. As a first step, freezing levies or tax rates might be needed to accomplish this. Pension reform and changes to collective bargaining laws will be crucial to holding government costs down.74 Consolidating many of Illinois’ nearly 6,000 taxing districts would help streamline operations and reduce costs as well.75

Endnotes

- Nathan B. Anderson and Daniel McMillen, “Why Is the Property Tax So Unpopular?” Institute of Government & Public Affairs Policy Forum, vol. 22, no. 3, April 2010; see also Matt Moon, “Special Report: How Do Americans Feel About Taxes Today?” Tax Foundation, April 2009, (finding 25 percent of survey respondents considered local property taxes “not at all fair,” while only 5 percent considered property taxes “very fair”); Gallup, poll, April 2005, (a plurality of 42 percent of respondents said local property taxes were the least fair tax, compared with 20 percent who said the federal income tax was the least fair tax).

- See, e.g., Jason Grotto, “An Unfair Burden,” Chicago Tribune, June 10, 2017.

- See, e.g., Rick Pearson, “Chris Kennedy Calls Property Tax System ‘Extortion,’” Chicago Tribune, May 30, 2017; “Candidate Q&A: Daniel Biss, Democratic Candidate for Illinois Governor,” Rock Island Dispatch-Argus, March 1, 2018.

- U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, one-year estimates (table S2506).

- Ibid.

- Median effective property tax rates calculated using median household value and median property tax paid in each state according to U.S. Census Bureau, 2016 American Community Survey, one-year estimates.

- Orphe Divounguy, “Rising Property Tax Burdens Squeeze Illinois Families,” Illinois Policy Institute.

- Illinois spent the second-most per student in the Midwest and the 13th-most in the nation in fiscal year 2015. Bryce Hill, Joe Tabor, “Illinois Spends More on Education, but Outcomes Lag,” Illinois Policy Institute, February 25, 2018. And Illinois school districts collectively spend more per year on administrative costs than school districts in any other state. Andy Shaw, “How Illinois Schools Could Spend More in the Classroom – Without Raising Taxes,” Crain’s Chicago Business, March 31, 2017.

- Illinois Department of Revenue, Illinois Property Tax System, 10, 19.

- 35 Ill. Comp. Stat. 200/9-145.

- The Illinois Property Tax Code allows county boards to divide their counties into four assessment districts in order to stagger general assessments; St. Clair County’s assessment system is structured this way. See 35 Ill. Comp. Stat. 200/9-225.

- 35 Ill. Comp. Stat. 200/9-220. Cook County’s assessment areas are divided into the north suburbs, the city of Chicago and the south suburbs. The general assessments for these three areas are staggered. Cook County Board of Review, Township Triennial Reassessment Schedule.

- International Association of Assessing Officers, Standard on Property Tax Policy, full revision approved January 2010, 9.

- International Association of Assessing Officers, Standard on Mass Appraisal of Real Property, 2017, 10-11.

- The Illinois Department of Revenue states the formula as: COD = average deviation ÷ median x 100%. Illinois Department of Revenue, Publication 136: Property Assessment and Equalization, 12.

- International Association of Assessing Officers, Standard on Mass Appraisal of Real Property, 2017, 11.

- International Association of Assessing Officers, Standard on Ratio Studies, 2013, 19.

- Illinois Department of Revenue, Sales Ratio and Equalization Tables, Table 1: Assessment Ratio.

- Illinois Department of Revenue, Assessment Ratios 2016.

- International Association of Assessing Officers, Standard on Ratio Studies, 19; Illinois Department of Revenue, Assessment Ratios 2016.

- Ibid.

- Illinois Department of Revenue, Assessment Ratios 2016.

- Illinois Department of Revenue, Assessment Ratios 2016.

- While commercial properties in smaller, less urban areas can have an upper COD of 20, and assessments of residential properties in similar, newer neighborhoods can have an upper COD of 10, the Illinois Property Code contemplates a COD of 15 as the acceptable upper limit for counties such as DuPage, Lake and St. Clair. This is seen in the provision of performance bonuses for assessors in counties with populations of 50,000 to 3,000,000. These bonuses are awarded only to assessors who have achieved CODs of 15 or less, along with assessment levels near the statutory 33 1/3 percent. 35 Ill. Comp. Stat. 200/4-20. Though the Cook County assessor is not eligible for a performance bonus under the statute, according to industry standards, a COD of 15 should apply to both Cook County residential and commercial assessments.

- Illinois Department of Revenue, Property Assessment and Equalization, 11.

- The Illinois Department of Revenue states the formula as: PRD = Mean assessment ratio ÷ sales-based average ratio. Property Assessment and Equalization, 12.

- Illinois Department of Revenue, Property Assessment and Equalization, 11; International Association of Assessing Officers, Standard on Mass Appraisal of Real Property, 11.

- Illinois Department of Revenue, Assessment Ratios 2012-2016.

- See Jason Grotto and Sandhya Kambhampati, “Commercial Breakdown,” Chicago Tribune, December 7, 2017; Austin Berg, “Investigation: Madigan Firm the Biggest Player in Commercial Property Tax Appeals,” Illinois Policy Institute, December 8, 2017.

- Jason Grotto, “An Unfair Burden,” Chicago Tribune, June 10, 2017; Jason Grotto and Sandhya Kambhampati, “Commercial Breakdown,” Chicago Tribune, December 7, 2017.

- Ibid.

- Civic Consulting Alliance, Residential Property Assessment in Cook County: Summary of Analytical Findings, February 15, 2018.

- Christopher Berry, Estimating Property Tax Shifting Due to Regressive Assessments: An Analysis of Chicago, 2011-2015, University of Chicago, March 2018.

- Grotto, “An Unfair Burden.”

- Ibid.

- Civic Consulting Alliance, Residential Property Assessment in Cook County.

- DuPage County Supervisor of Assessments, “Assessment Cycle Overview,”; DuPage County Supervisor of Assessments, “Equalization Factor Calculation Background,”.

- Lake County Chief County Assessment Office, “Sales Ratio Studies,”.

- Call with personnel in St. Clair County Assessor’s Office, April 18, 2018.

- Illinois Department of Revenue, Illinois Property Tax System, 10.

- Lake County website, “How Is the Value of Real Property Assessed?”.

- Illinois Department of Revenue, Illinois Property Tax System, 11.

- York Township Assessor’s Office; Lake County, “How Is Real Property Assessed?”.

- Cook County Assessor’s Office, “How Residential Property Is Valued,”.

- Illinois Department of Revenue, Illinois Property Tax System, 11.

- Ill. Con. art. IX, § 4.

- Illinois Department of Revenue, Illinois Property Tax System, 14.

- Cook County Code of Ordinances, Art. II, Div. 1, Sec. 74-63; Richard F. Dye, State-by-State Property Tax at a Glance Narratives: Illinois, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, February 2018.

- Cook County Assessor’s Office, “Definitions for the Codes for the Classification of Real Property,”.

- 35 Ill. Comp. Stat. 200/9-145.

- For example, Missouri assesses residential property at 19 percent and commercial property at 32 percent of value. State Tax Commission, Property Reassessment and Taxation, revised January 2017; Michigan assesses real property at 50 percent of market value. State Tax Commission, Guide to Basic Assessing, January 2018.

- Joan Youngman, A Good Tax: Legal and Policy Issues for the Property Tax in the United States, (Cambridge: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2016) 98-102.

- Youngman, A Good Tax, 102.

- Robert L. Beebe and Richard J. Sinnott, “In the Wake of Hellerstein: Whither New York,” Albany Law Review 43(3) 482-83 (1979), cited in Youngman, A Good Tax, 102.

- Ibid.

- International Association of Assessing Officers, Standard on Property Tax Policy, 19.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- John A. Miller, “Rationalizing Injustice: The Supreme Court and the Property Tax,” 22 Hofstra L. Rev. 79, n. 17 (Fall 1993), citing Diana B. Paul, The Politics of the Property Tax 4-5 (1975).

- Andy Hultquist and Tricia L. Petras, “Determinants of Fractional Assessment Practice in Local Property Taxation: An Empirical Examination,” Proceedings. Annual Conference on Taxation and Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the National Tax Association Vol. 105, 105th Annual Conference on Taxation (November 15-17, 2012), 147.

- Va. Code. Ann. § 58.1-3201.

- Wis. Stat. § 70.05(5)(b).

- ALM GL ch. 59, § 38.

- International Association of Assessing Officers, Standard on Property Tax Policy.

- Benjamin H. Harris and Brian David Moore, “Residential Property Taxes in the United States,” Tax Policy Center of the Urban Institute and Brookings Institution, November 18, 2013, 3.

- International Association of Assessing Officers, Standard on Property Tax Policy.

- Ibid.

- MCLS § 211.10.

- State Tax Commission, Property Reassessment and Taxation, (Jefferson City, Mo., revised January 2017), 3.

- Iowa Department of Revenue, Iowa Property Tax Overview.

- See DuPage County Supervisor of Assessments, “Equalization Factor Calculation Background,” (noting Illinois’ three-year sales data period “somewhat disconnect[s] the timely relationship between property values and property assessments”).

- See International Association of Assessing Officers, Standard on Ratio Studies, 10-11.

- See Jeremy Horpedahl, “Principles of a Privilege-Free Tax System, with Applications to the State of Nebraska,” working paper, Mercatus Center, September 2014, (noting that from an economic and a tax transparency standpoint, it is preferable to apply exemptions to low-income taxpayers rather than to all individuals). See also Nathan B. Anderson, “No Relief: Tax Prices and Property Tax Burdens,” Regional Science and Urban Economics 41 (2011), 548 (explaining that “homestead exemptions do not produce reductions in average residential property tax payments” and that “elimination or reduction of these relief programs is likely not to result in property tax increases for homeowners, but rather declines in commercial-industrial tax payments and public expenditures”).

- See, e.g., Ted Dabrowski, “Rahm Trades Reform for the Largest Property-Tax Hike in Chicago’s Modern History,” Forbes, October 26, 2015; Mailee Smith, “Rigged: How Illinois’ labor laws stack the deck against taxpayers,” Illinois Policy Institute, Winter 2017.

- Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner, “Too Many Districts: Illinois School District Consolidation Provides Path to Increased Efficiency, Lower Taxpayer Burdens,” Illinois Policy Institute, Spring 2016.