Introduction

Education is meant to be the great equalizer that lets every child reach his or her potential.

But a review of the achievement gap between Illinois’ white and Hispanic students raises serious concerns about the ability of Illinois’ public schools to prepare Hispanics for success in an increasingly competitive economy.

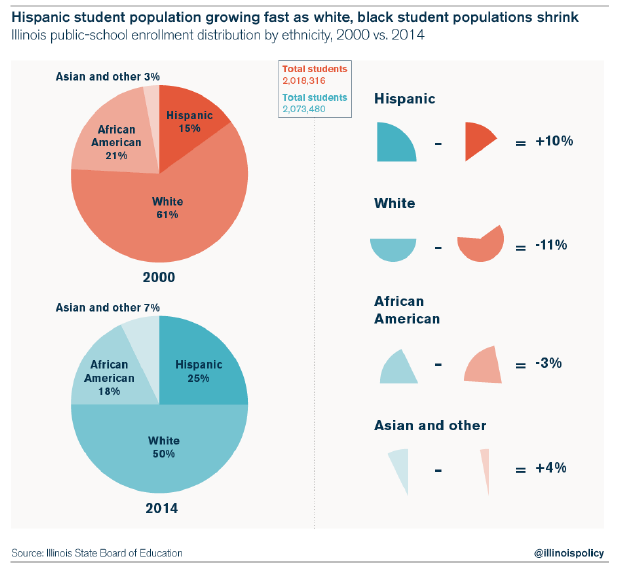

With Hispanics now making up the largest minority population in Illinois,1 their level of achievement will have a large impact on the state’s economic future.

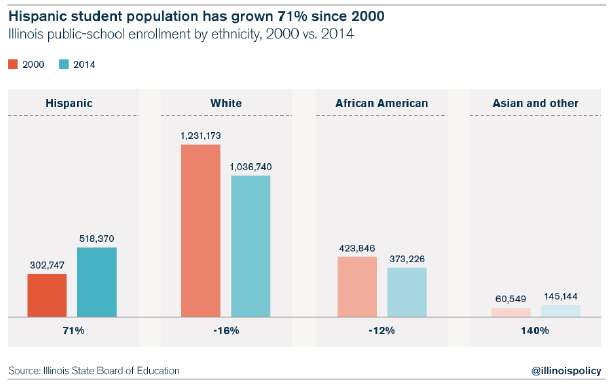

The state’s total Hispanic population jumped by 32 percent between 2000 and 2010, and now exceeds 2.1 million, or 17 percent of Illinois’ total population.

The Hispanic student population now makes up a quarter of the state’s entire student body and nearly 50 percent of the students in Chicago Public Schools, or CPS.2

This report outlines the achievement gaps that exist between white and Hispanic students in Illinois’ public schools, and shows the need to fundamentally reform the education system.

Illinois' hispanic achievement gap

The gap between white and Hispanic students in reading and math is alarming and the overwhelming majority of Illinois’ Hispanic high-school students aren’t graduating college- or career-ready. For many Hispanic students, the learning gap will mean continuing hardship.

Research shows that students who lack basic math and reading skills are more likely to drop out of high school, are incarcerated at higher rates, are more likely to enroll in public assistance programs and will make significantly less money than their peers who receive a quality education.3

This gap has persisted over many years, but real reforms have been lacking. More money and a bigger bureaucracy for the public-school system have not created positive results.4,5

Some proponents of the status quo are quick to blame Hispanic parents and their children for poor educational outcomes, saying parents aren’t engaged and that children aren’t prepared. Others blame poverty and language barriers. Still others fault the state’s education-funding system as ineffective, despite the fact that most of these districts receive more than 50 percent of their funding from state and federal sources.6

Sadly, those excuses have led many schools to lower their expectations and move children through the educational system, whether they are ready for the next grade or not.

State policymakers have a choice. They can blame the parents and the students for the Hispanic achievement gap, maintain the status quo and bear the socioeconomic consequences, or they can evolve how Illinois teaches and motivates its Hispanic children.

What lawmakers can’t afford to do is ignore the state’s burgeoning Hispanic student population.

Illinois' hispanic students have fallen behind

Reading is the gateway to learning. If children can’t read at grade level by the third grade, they’ll face significant learning challenges in later years.

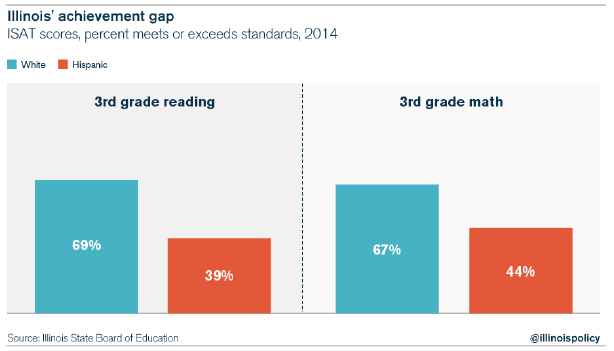

Illinois Standard Achievement Test, or ISAT, results show that only 4 in 10 Hispanic third-graders in Illinois can read at grade level. Third-grade students who don’t meet the reading standards are unable to distinguish between the main idea and supporting details of a story. The chance that these students drop out of school later rises dramatically, according to research from the Annie E. Casey Foundation.7

By comparison, 69 percent of white third-graders in Illinois can read at grade level, resulting in a yawning 30 percentage point achievement gap between whites and Hispanics.

The ISAT math results are equally alarming, though not quite as stark, with a 23 percentage point achievement gap.

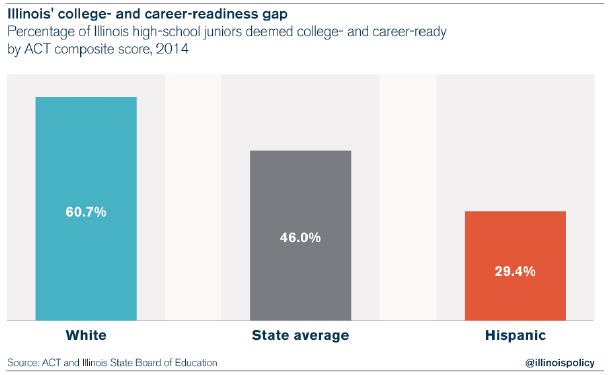

Predictably, this same achievement gap persists into high school. Under Illinois law, every junior in the state is required to take the ACT – a national test that most Midwestern students take if they want to attend college.

According to the Illinois State Board of Education, or ISBE: “a college-ready composite score of 21 or higher on the ACT shows that students have learned important academic skills that they will need in order to succeed in college and careers.”

Only 29.4 percent of Hispanic students graduate college- and career-ready, as determined by their ACT scores.

By comparison, 60.7 percent of whites are college- and career-ready. That’s a 31 percentage point gap when compared to Hispanic students in Illinois.8

An examination of Illinois' majority hispanic districts

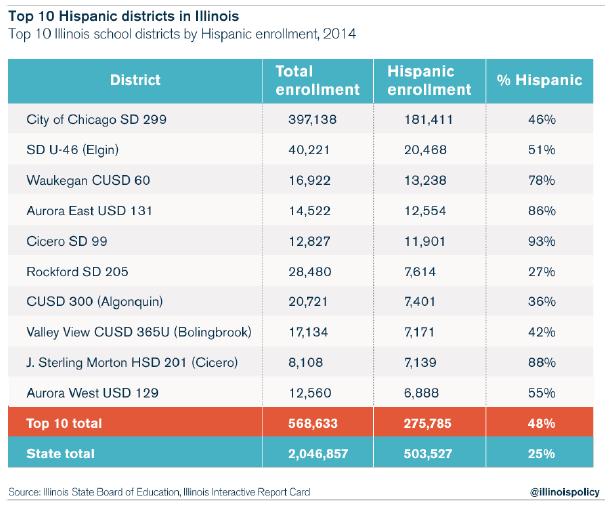

An analysis of Illinois’ student population shows that nearly 55 percent of the state’s total Hispanic student population is located in just 10 school districts.

This concentration of Hispanic students allows for a closer look at how some of those districts are performing. And districts that are more than 75 percent Hispanic can serve as a proxy for how the educational system has failed to adapt to its growing Hispanic population.

Case study: Waukegan CUSD 60

Historically a successful manufacturing and trading hub, Waukegan, Illinois, companies began shuttering their factories as manufacturing in the Midwest took a hit in the 1970s and ’80s. Gone are the many companies that formed the economic backbone of Waukegan, hurting the city’s economy, its job market and housing values.

The collapse in manufacturing led to a massive shift in the city’s demographics. Hispanic and black families moved to a more affordable Waukegan in search of the same educational opportunities and stability promised in other northern suburbs of Chicago.

Hispanics now make up more than half of Waukegan’s total population and Hispanic students represent nearly 75 percent of the population in Waukegan schools. Seventy-two percent of its student population is now low-income.9

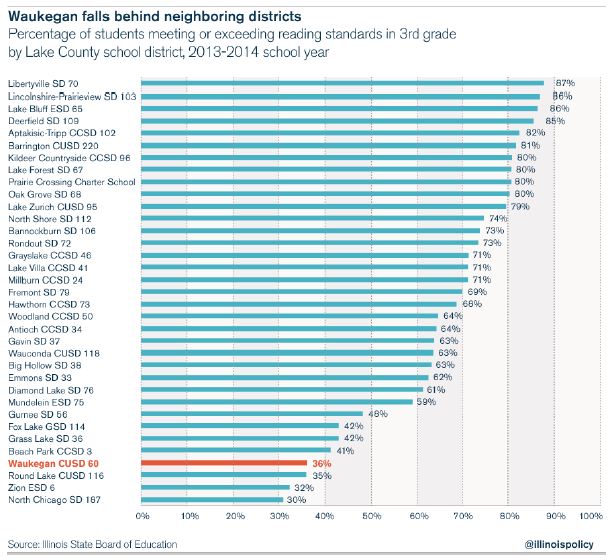

But despite its proximity to some of the best-performing school districts in Lake County and the state, Waukegan’s educational results more resemble those of an urban, inner-city school district.

Only 36 percent of Waukegan’s third-graders read at grade level, significantly below the average in Lake County.

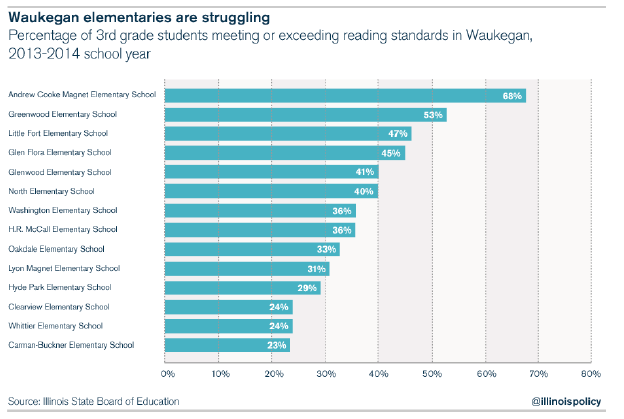

Those troubling results are prevalent across all the schools in the district. Even Waukegan’s magnet schools suffer from low reading scores.

And at its lowest performing school, Carman-Buckner, only 1 in 4 students can read at grade level.

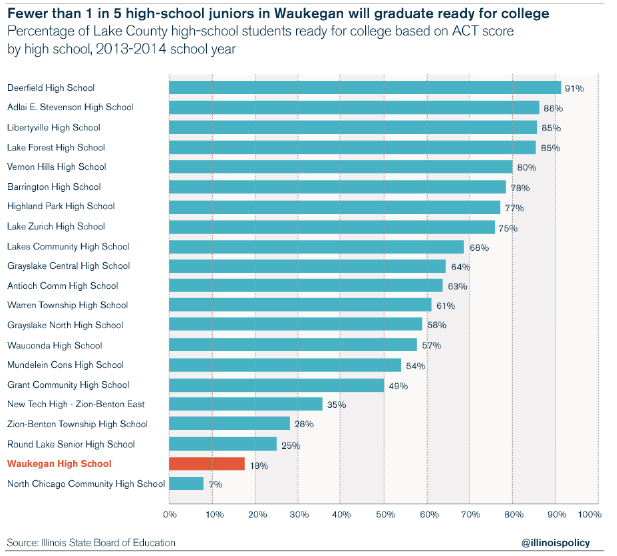

With such low reading scores during pivotal learning years, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that only 18 percent of Waukegan’s high-school juniors will graduate college- or career-ready.

Case study: Cicero SD 99

Over 90 percent of the nearly 13,000 students enrolled in Cicero SD 99 are Hispanic. This allows for an almost direct comparison between it and other school districts that have small-to-insignificant Hispanic populations.

Sadly, the achievement gaps become even more visible.

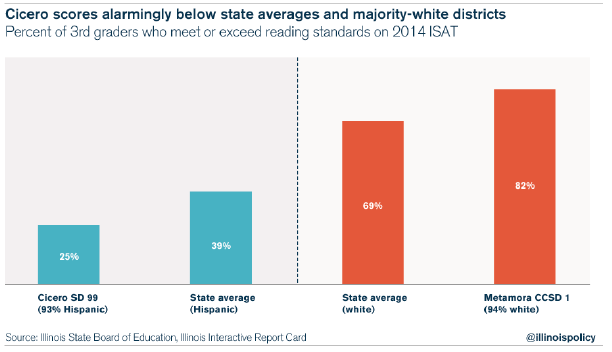

Only a quarter of Cicero’s third-graders can read at grade level. That’s short of the 39 percent state average for Hispanics.

But the gap is more dramatic when compared to the state average for whites (69 percent) or a higher-performing, low per-student spending, significantly white district located downstate (Metamora CCSD 1: 82 percent).

The poor performance of Cicero’s elementary students continues on to high school. At J. Sterling Morton HSD 201, one of the high-school districts for which Cicero SD 99 is a feeder district, only 18 percent of juniors will graduate college- or career-ready.10

Case study: City of Chicago SD 299

City of Chicago SD 299, the official title of Chicago Public Schools, or CPS, merits attention because it is the largest Hispanic district in Illinois, with more than 180,000 Hispanic students. Nearly half (46 percent) of CPS students are Hispanic.

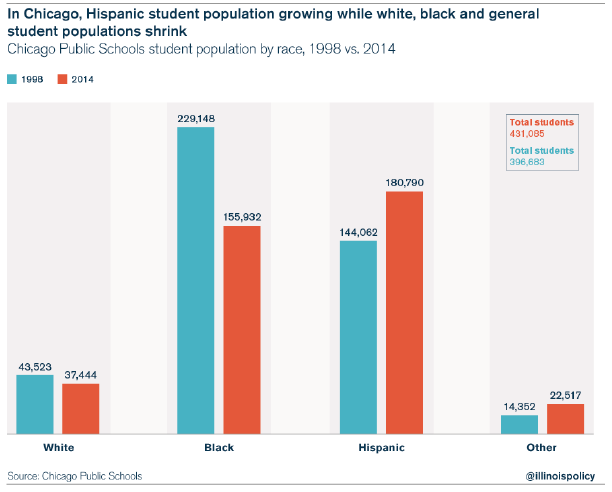

The growth in the number of Hispanic students is remarkable given the downward trend of Chicago’s general student population. From 1998 to 2014, the Hispanic student population grew 25 percent – even as the district’s general student population fell by 7 percent.11

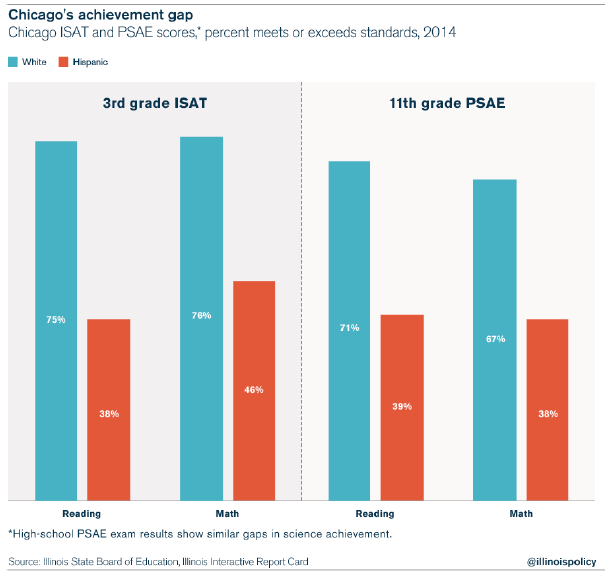

The achievement gaps between white and Hispanic students in Chicago in 2014 are larger than the state’s averages. Over 75 percent of white third-grade students in Chicago can read at grade level, compared to only 38 percent of Hispanic students. That’s a gap of 37 percentage points – seven points higher than the average state gap between white and Hispanic students.

The gap in student achievement continues on to high school – 39 percent of 11th-grade Hispanic students can read at grade level, compared with 71 percent of white students.

This divergence in success is responsible for Chicago’s poor overall achievement levels. By the time they graduate from high school, only 27 percent of Chicago’s students will be ready for college coursework.12

Conclusion

There’s no disputing Hispanics are a growing demographic force within Illinois. With their increasing influence on the socioeconomic future of the state, Illinois must reduce the Hispanic educational achievement gaps.

This analysis focuses on these gaps to highlight the tremendous challenge – and the amazing opportunity – Illinois educators and policymakers face. Such low academic results mean there is dramatic room to improve the lives of Hispanic children and their families.

Every single child in Illinois deserves access to a high-quality school, no matter their neighborhood, how much money their parents make or their ethnicity.

But in many Illinois communities, including those included in this analysis, that access won’t happen by making marginal improvements to the existing educational system. Too many children have been, and will be, left behind.

Instead, Illinois should lead through innovation by offering families and children more educational options and access to a variety of school types, whether public or private, big or small.

Today, only families with financial means can afford to choose schools that best meet the needs of their children, whether by sending them to private schools or by moving to a district in a different community.

But parents without financial means – many Hispanic – don’t have those same options. Instead, they are forced to go to schools based on their ZIP code, not their needs. Many are captive to a system that has repeatedly failed to adapt and address the needs of the community.

Fortunately, more than 25 states across the country, including Wisconsin and Indiana, are now finding ways to engage more families in the education of their children. These states offer parental choice in education in the form of school vouchers or educational savings accounts.13

Under these programs, parents – not bureaucrats – decide where their children go to school and how and what they learn.

Nevada, the most recent state to pass a school-choice program, is offering education savings accounts to every single one of its 385,000 public-school students.14

Nevada parents now have the right to access over $5,000 in state funds to spend on a variety of educational options: from private schools and online classes, to tutoring programs and other learning interventions. These parents now have greater control over their children’s future, allowing them to match various educational offerings with their children’s individual needs and learning styles.

Illinois parents should have the same right as parents in Nevada and other school-choice states.

Their children can’t afford to wait.