Published Jan. 28, 2025

Illinois Policy Institute Center for Poverty Solutions, in partnership with the Archbridge Institute

By Joshua Bandoch, Ph.D., head of policy, Illinois Policy Institute and Justin Callais, Ph.D., chief economist, Archbridge Institute

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

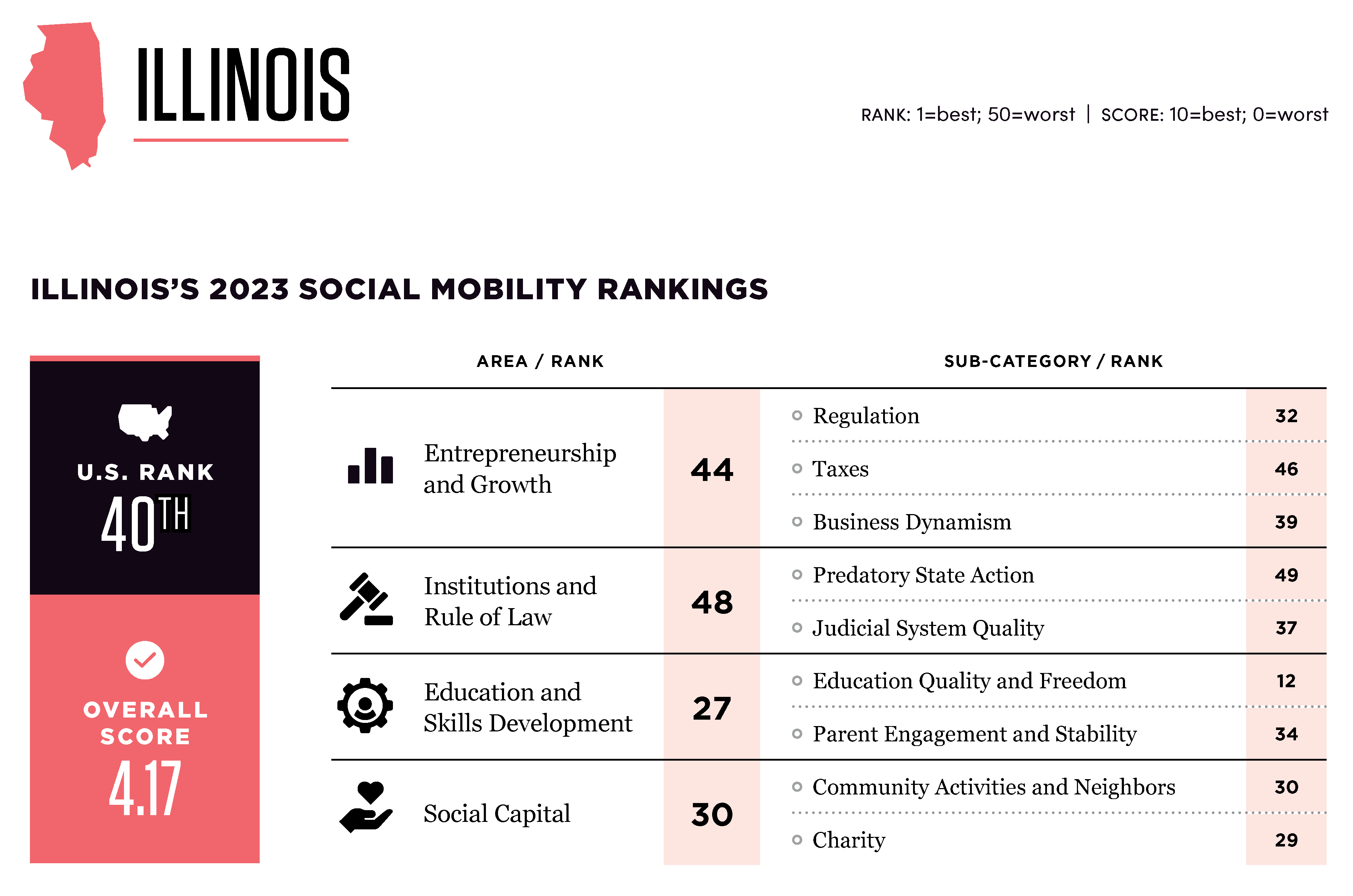

A low-income person’s ability to move up in society is worse in Illinois than in any other Midwestern state, and 40th lowest nationally. Illinois is below average on each of the four aspects determining social mobility – entrepreneurship and economic growth, institutions and the rule of law, education and skills development, and social capital. The state scores particularly low on the first two. Low social mobility puts opportunity and the American Dream out of reach for many Illinoisans, especially the poor, disadvantaged and minorities.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Many of the problems contributing to Illinois’ inequitable lack of opportunity are the product of harmful man-made policies. This means they have man-made solutions.

Illinois’ elected leaders have a chance to turn the state into a true “opportunity society” that empowers people to unleash their potential. This report provides a reform agenda for how Illinois can become a leader in social mobility. Here are the top recommendations to achieve that:

Introduction

Around the globe, America is seen as the land of opportunity. Social mobility, otherwise known as upward mobility,1 is central to this perception of America as a place where individuals are empowered to pursue happiness and capitalize on opportunities. It entails being able to better yourself and those around you economically and culturally, enabling individuals and our nation to prosper. That’s the American Dream. Hundreds of millions of people have left countries they once called home to move here, create a better life and turn that dream into their reality. Many more would do so if they had the chance.

Social mobility has four pillars: entrepreneurship and economic growth, institutions and the rule of law, education and skills development and social capital. These pillars include business dynamism, corruption perceptions, education quality and community involvement. Strength in these pillars allows people to unleash their potential. Weakness holds them back.

While the U.S. ranks 27th out of 82 countries globally in social mobility,1 the reality is when we measure opportunity based on the above pillars, we see it is unfairly distributed across the 50 states. According to a 2023 report published by the Archbridge Institute called “Social Mobility in the 50 States,” in some states such as Utah and Minnesota, opportunity abounds.2 In others, such as New York and Louisiana, far too many people are blocked from accessing opportunities to pursue happiness. That’s inequitable.

Even within geographical regions with similar demographics, social mobility differs greatly among states. Consider the Midwest: Social mobility is highest in Minnesota, which ranks second overall nationally. North Dakota, South Dakota and Nebraska are also in the top 10 nationwide. Illinois has the worst social mobility in the Midwest, with a national ranking of 40th that is well behind second-worst Ohio at No. 32. Such low social mobility leaves many Illinoisans unfairly stuck. That’s a pathway to despair and dependency, not opportunity and prosperity. It’s bad for everyone and explains why hundreds of thousands of Illinoisans have fled the state in recent years.

This report examines what accounts for Illinois’ worst-in-the-Midwest ranking in social mobility. What are the biggest barriers to opportunity in the state? What reforms are necessary to remove those barriers and empower more Illinoisans to unleash their potential? What reforms would turn Illinois into a state where opportunity is not only possible but probable? Most importantly, what would make Illinois a leader in social mobility? This report investigates these questions and makes recommendations for improving social mobility in Illinois based on the four pillars listed above.

The barriers Illinois faces are largely man-made inside the pillars of entrepreneurship and economic growth and institutions and the rule of law. They include factors such as weak business innovation and enthusiasm, an extremely burdensome regulatory environment, too many housing restrictions, high taxes, low judicial quality, and far too much predatory state action.

States often just need to be well-balanced and average across many indicators, and stand out in a few, to really prosper. A lot of modest improvements add up to significant increases in social mobility.

Social mobility’s importance

Social mobility is the opportunity to better yourself and those around you. We commonly think of social mobility in economic terms: is someone able to climb the income ladder and outearn the previous generation? It’s actually much broader. It’s also concerned with achievement, aspirations, meaning, reputation and skills development. It’s about businesses growing, individuals working, access to good education, the quality of the judicial system and high levels of community involvement.

Social mobility is foundational to any successful society. People need to know that if they work hard and create value, they can get ahead. When that isn’t true, or even when people feel like that isn’t true, society becomes unfair and inequitable. People despair because they don’t see a path forward for themselves and those they care about. Society suffers. Low social mobility hurts everyone.

Barriers to achievement play a large role in social mobility because they can dictate whether and how much mobility is possible. These barriers can be natural or artificial. Natural barriers occur at the individual level. These barriers are challenging to address, and only some of them can be remedied. For example, someone who is 6-foot-9 has a higher chance of becoming a professional basketball player than someone who is 5-foot-2, and there’s little a 5-foot-2 person, or anyone else, can do about it. Someone who excels in math has a better chance of becoming an engineer than someone who struggles despite lots of studying.

Artificial barriers, by contrast, are imposed by external forces such as the government. For example, state governments regulate whether someone can work in many industries such as interior design and cosmetology through occupational licenses. These government-issued permission slips to work create significant and often insurmountable barriers to individuals, especially those who can least afford them: the poor.

Public policy can address artificial barriers, particularly the ones it created in the first place. Regulatory barriers that make it more costly to start and operate a business are artificial barriers. Simply removing them will allow for those businesses to prosper more easily. While a lack of parental and family involvement is a natural barrier in a child’s life, policies that make achieving academic success in the classroom difficult, such as bans on school choice proposals, are artificial.

Perceived social mobility is declining in America

In recent years, many Americans have started to perceive social mobility and the American Dream itself to be fading. A Wall Street Journal/NORC survey asked voters in October 2023 whether the American Dream “still holds true.” Barely one-third (36%) said it did. That’s a 17-percentage point drop from the 53% who agreed in 2012, and a 12-percentage-point decline from the 48% who said so in 2016. When asked if life in America was worse than it was 50 years ago “for people like you,” 50% agreed it is.3

Americans appear to be questioning the value of hard work, too. In a January 2024 ABC/Ipsos poll, only 27% of respondents agreed “if you work hard, you’ll get ahead.” That’s down by nearly half from 2010, when 50% agreed. Pessimism about hard work was most pronounced among Blacks and young adults. In 2010, 55% of Blacks and 56% of young adults agreed with that statement, and in 2024 it was down to 21% among both groups.4

Not all surveys find the same pessimism. An April 2024 Pew survey found 53% of respondents agreed “the ‘American Dream’ is possible to achieve,’ with 41% saying it was once possible but no longer is.5 An August 2024 survey by the Archbridge Institute reported 67% of Americans saying they have achieved or are on their way to achieving the American Dream.6

Even these surveys separate along generational lines. In the Pew survey, 61% of Americans 50-64, and 68% 65 and older believe it’s still possible, while only 43% of those 30-49, and a mere 39% ages 18-29 agree. Similarly, in the Archbridge survey, 40% of 18- 29-year-olds, and 41% of 30-44-year-olds agree with the statement, “You believe most Americans can achieve the American Dream.” Even only 53% of 45-59-year-olds agree.

One troubling trend consistent across surveys is the belief in the American Dream appears to be fading among younger Americans. If this continues, and young Americans carry this pessimism about social mobility with them throughout their lives, it’s hard to see how the American Dream can last.

How to measure social mobility

We dissect the state of social mobility in Illinois based on a report published in 2023 by the Archbridge Institute called “Social Mobility in the 50 States.”7 States were ranked based on various factors that academic research has previously shown are important for social mobility. Four pillars of social mobility were considered, using 43 variables affecting social mobility: entrepreneurship and economic growth, institutions and the rule of law, education and skills development, and social capital. States’ final rankings were determined based on combined scores across these four pillars.

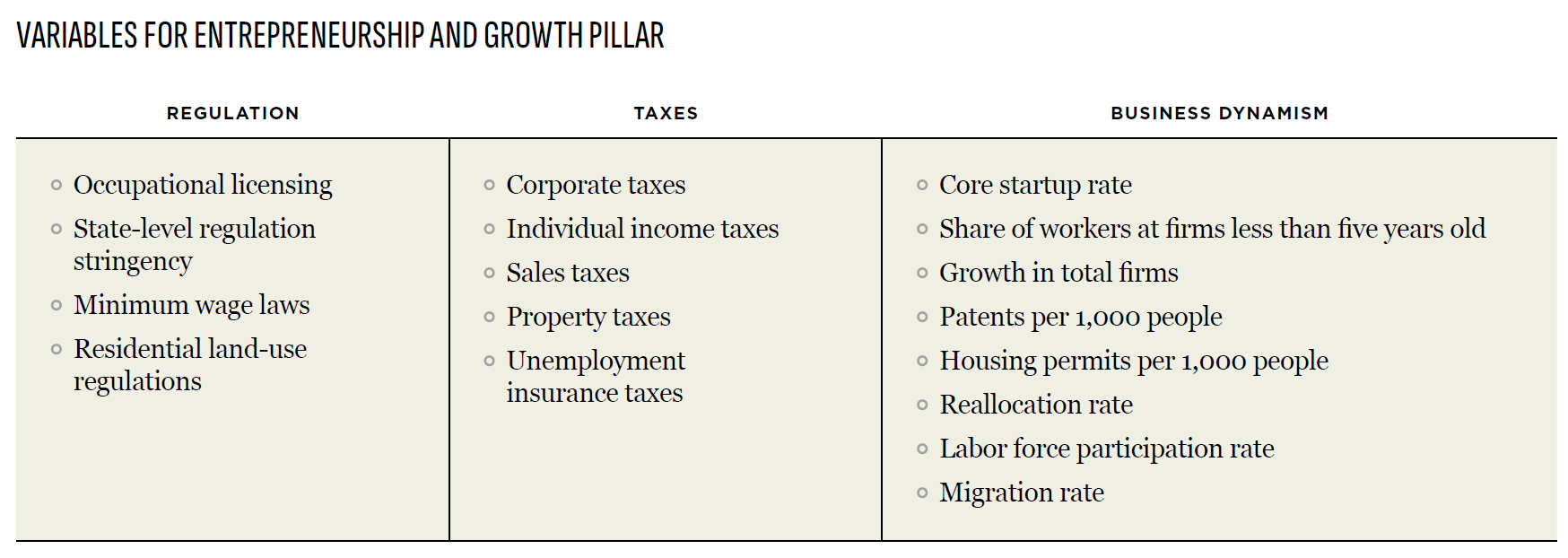

The first pillar is entrepreneurship and economic growth. Social mobility can best be achieved through work. Careers and jobs enable someone to achieve fulfillment and find practical ways to raise their relative standing in life while earning a steady living. Those at the top have access to opportunity. Broad-based economic growth is crucial because it provides relatively more opportunities for those at the bottom of the income ladder. Given that entrepreneurship and innovation are key drivers of economic growth, we consider variables that impact job creation, economic growth, and entrepreneurship. We also look at housing affordability, because where people can live plays a key part in their economic opportunities.

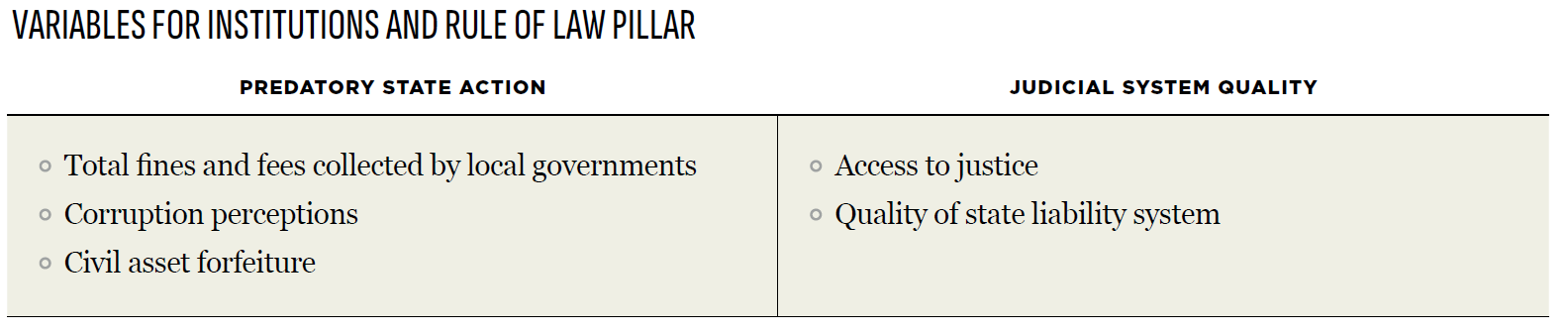

The second pillar considered is institutions and the rule of law. The quality of institutions such as the judicial system and laws are crucial factors for economic prosperity. Corrupt institutions and predatory state action usually benefit those at the top. Even worse, they are often used to target disadvantaged groups who are usually at the bottom of the income ladder, because they do not have the political connections and capital to craft the rules in their favor. Here, the index captures predatory state action (civil asset forfeiture and collection of fines and fees, for instance), as well as judicial system quality, which ensures rights are protected.

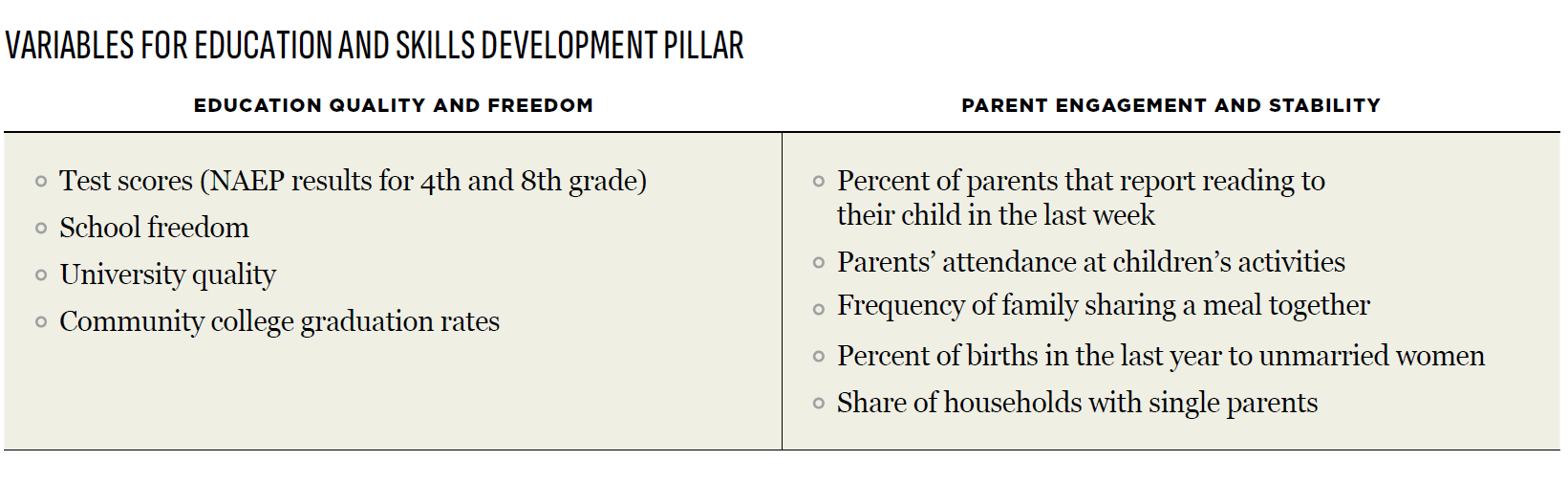

The third pillar is education and skills development, which is a key predictor of future opportunities. This includes the set of “hard” and “soft” skills learned throughout one’s life through formal and informal training. The index considers access to education and education quality during one’s life. This pillar also includes parental involvement in children’s lives and the stability of family homes because education acquired in the home is at least as important as classroom instruction.

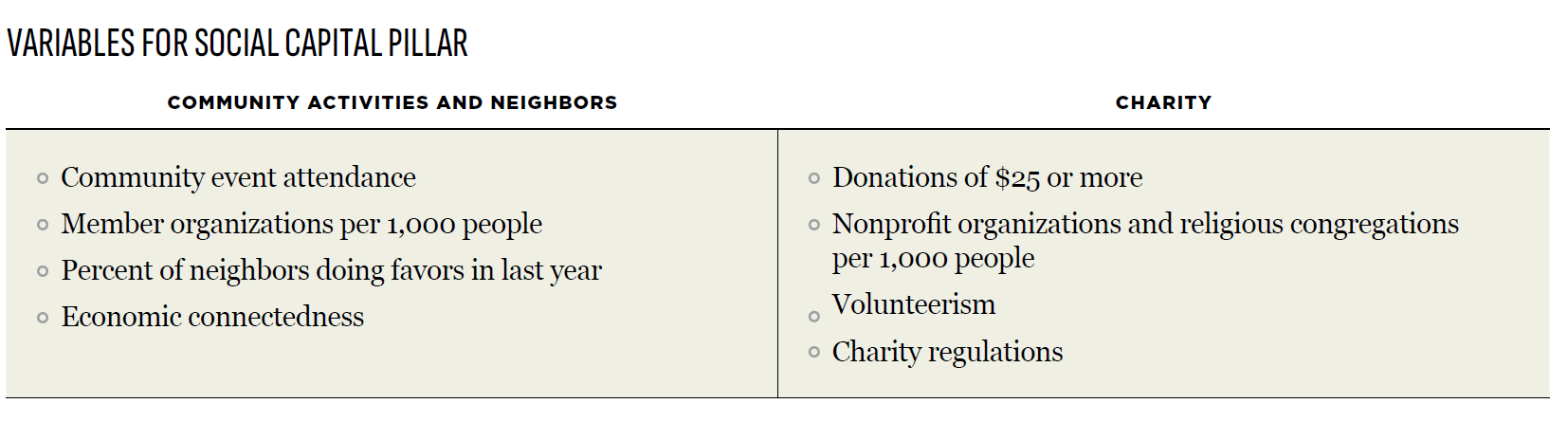

The fourth pillar is social capital. Broadly speaking, it is used to describe how individuals engage in communities and help each other. Two major sub-areas are considered here: community involvement and charity. Community involvement addresses variables that proxy how individuals engage with one another, from helping neighbors, to participating in public events, to joining membership organizations. Membership includes ways in which a state’s people decide to pursue volunteer activities (both financially and with their own time), as well as the legal barriers that prevent them from doing so.

Social mobility in Illinois

In this section we assess the state of social mobility in Illinois across these four pillars and 43 total variables. This section is purely observational. Subsequent sections provide policy recommendations for how Illinois can improve social mobility.

Entrepreneurship and growth

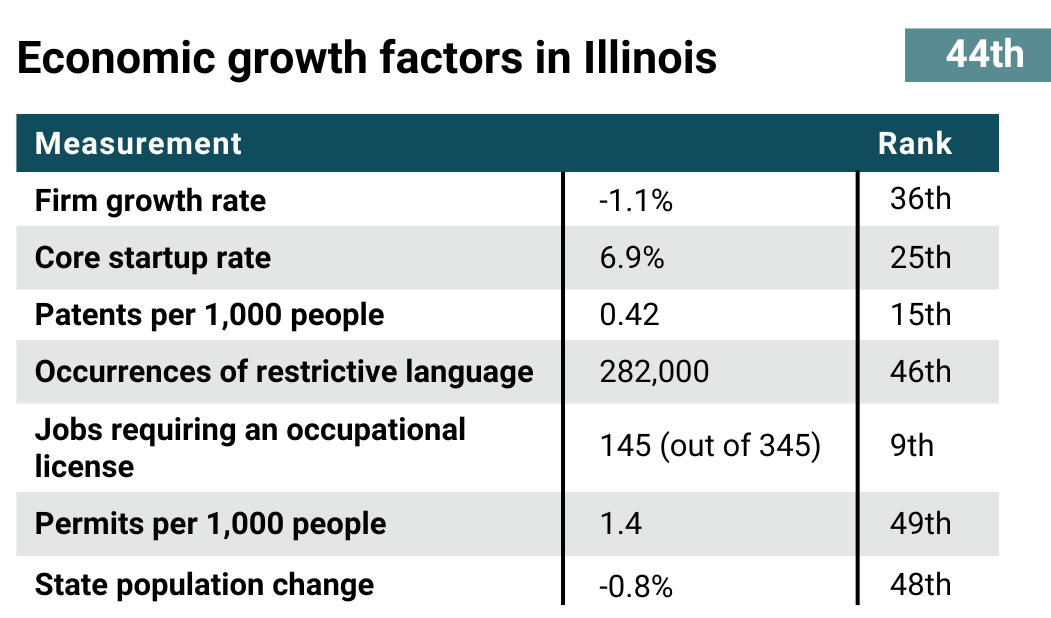

Illinois scores a lowly 44th in the “entrepreneurship and economic growth” pillar of social mobility, well behind all Midwestern states. This result is primarily driven by a lifeless business environment stifled by burdensome regulations and high taxes.

Business dynamism in Illinois is lagging because the number of companies is shrinking and not enough new ones are taking their place. Illinois experienced negative firm growth of 1.11% in 2021, losing on net just over 2000 establishments. That puts it 36th in the country. High-profile firms that have left in recent years include Citadel, Guggenheim, Boeing, and Tyson Foods. They take with them critical economic activity, including thousands of well-paying jobs. The core startup rate, which gauges a state’s ability to encourage the production of new businesses, is 6.9%, placing Illinois right in the middle of the country’s rankings. Patents, another measure of business dynamism, considers the more innovative side of a state’s economy. Here, Illinois has roughly 0.42 patents per 1,000 people, placing it 15th in the country.

Illinois’ punishing regulatory regime is holding the state back, making it hard for businesses to operate and for individuals to innovate. Regulatory stringency, measured by the number of instances of language in the legal code that restrict business activity, is quite high in Illinois. As of 2021, Illinois had over 278,000 instances of restrictive language on its books, which is fourth highest in the country behind California, New Jersey and New York, according to data from the Mercatus Center.8 That number continues to balloon: in 2017, there were 259,000 such restrictions. By 2023, this number has risen to 282,000. For comparison, the average among states is 135,000, meaning Illinois has more than double the average. Idaho has the fewest with only 39,000.

One problematic regulation we consider is occupational licensing, which is a government permission slip to work in particular professions. Relative to other states, Illinois licenses fewer professions. Illinois licensed 145 out of the 345 licenses examined in the Archbridge Institute’s State Occupational Licensing Index report. The state ranked ninth in the country for fewest licenses and barriers.9

In absolute terms, Illinois’ occupational licensing regime places significant burdens on Illinoisans, particularly those most in need of opportunity. University of Minnesota professor Morris Kleiner found in 2015 that 24.7% of the Illinois workforce is licensed, and 5% was workforce certified.10 As of August 2024, Illinois’ workforce was 6.52 million individuals.11 As licensing requirements have stayed approximately the same, in part because of the state’s dormant sunset review process, that means 1.61 million Illinoisans need some sort of government permission slip to work. That’s far too many.

There are numerous odd occupational licenses in need of reform. For example, Illinois is one of just 12 states that mandates a license to be a locksmith, requiring a fee of over $500 and some barriers such as examination and previous education experience in the field. Similarly, Illinois is among the 22 states that require licensing to be a sign language interpreter. To apply for this license, an individual needs two years of education and a nearly $500 fee.

According to a report from the Institute for Justice examining licenses for lower-income careers, Illinois licensed 41 out of 102 possible careers. Thirty-five states have worse licensing burdens.12

Generally, it’s important for states to consider carefully whether a profession truly requires a license, because it often creates a significant barrier to entering a profession. When there are not substantial reasons to require a license, it is better to remove this barrier to work.

Part of fostering a growing, dynamic economy is ensuring housing affordability for current and future residents. Otherwise, they can’t access jobs because they’re too far from where they live, or they leave because they can’t afford to stay. Illinois is the least affordable state for housing in the Midwest. Nearly one-third (32.26%) of Illinois households are considered housing burdened, meaning they spend at least 30% of their income on housing.13 The key to achieving housing affordability is increasing housing supply. On this front, Illinois faces serious issues.

Illinois ranks 49th in approving permits to build housing, with just 1.4 permits annually per 1,000 citizens. The national average is nearly triple, at 4.3 per 1,000 citizens. Illinois is ahead of only Rhode Island’s 1.27 ratio. The Chicago area ranked dead-last among the 10 most populous metropolitan areas for new housing units approved per 100,000 residents, notching only 162. Houston led the way with 915, more than 5.5 times higher than Chicago.14

Land use regulations such as zoning laws dictate what sort of construction or adaptation – if any – is permitted on property. Illinois’ national ranking of 30th obscures that the state is second worst among Midwest states, ahead of only Minnesota.15 This score is being dragged down by Chicago and its surrounding areas. According to data collected by Chicago CityScape from 2019, in total, 41.1% of land in Chicago is specifically zoned for single-family housing. Only 20.8% is zoned for mixed use residential (multi-family housing) and commercial use.16 Residential property is not allowed on 25.1% of land in Chicago.

Illinois’ hefty tax burden also pulls down its social mobility scores. The state is ranked among the five states with the most burdensome tax codes. Only Connecticut, New Jersey, New York and Massachusetts have higher tax burdens. Illinois’ corporate tax rates, sales taxes and property taxes are some of the highest in the country. Higher tax rates change the incentive structure for individuals and businesses. Higher taxes encourage firms to relocate to lower-tax states, which hurts workers in the states they leave and harms the economy. Taxes suppress wages and decrease take-home pay. Sales taxes raise the purchasing price of goods and services purchased, forcing families to make tough decisions on which products to buy and pricing them out of some necessities. This in turn hampers social mobility, as individuals are now less able to achieve a higher socioeconomic status.

Another component of entrepreneurship and growth is net migration, because it’s an overall sign of how healthy a state is. If people see a state as having sufficient opportunity, they move there. If they feel like they can’t get ahead somewhere, they leave. That leads to the breakdown of communities. It hurts the economy, too, because people take their skills and innovation with them, and businesses struggle to replace them. Illinois’ demographic trends are deeply concerning.

Illinois is experiencing severe net outmigration. Illinois’ net migration rate is negative (-0.81%), with over 110,000 people leaving in 2021. That’s the third worst on net, behind only California and New York. All three states have received much media attention because of this issue since a negative number shows systemic problems in the state.

There are many reasons people choose to leave a state. One is housing affordability. Burdensome housing regulations push people to move to places where housing is more affordable. Another is taxes. Of Illinoisans who left in 2022, 97% went to states with lower taxes.17 We revisit taxes briefly below.

Institutions and the rule of law

High quality and unbiased legal systems and protection of private property are among the largest correlates of economic prosperity around the world and across America.

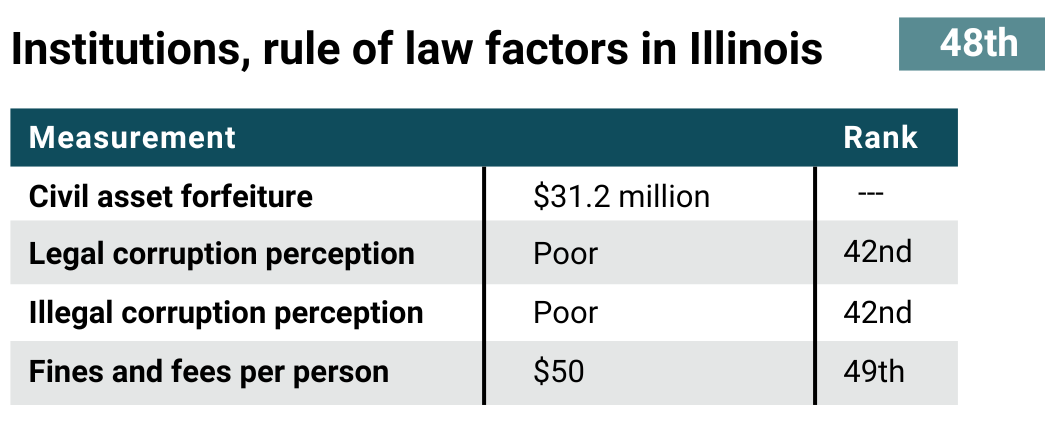

Illinois scores particularly low in the pillar of institutions and the rule of law. Illinois is 48th in the country, trailing just Alabama and Louisiana. This is largely because of poor scores on “predatory state action” which encompasses the reliance on fines and fees for local revenue, corruption perceptions and civil asset forfeiture laws.

The American judicial system is based on the ideal of “innocent until proven guilty.” Many states fail to hold up this ideal sufficiently, leading to potential injustices. One example of this is civil asset forfeiture, which allows states to seize and keep assets solely on the basis of probable cause, a much lower burden than the traditional “innocent until proven guilty” standard used in criminal legal procedures. The standard of proof needed to seize assets is one of the lowest in the country, again tied with many other states and only higher than Massachusetts. Massachusetts scored the worst, receiving an “F” grade according to research from the Institute for Justice. Illinois received a D-, along with over half of the states in the union.

As in many other states, Illinois places the burden on the owner to prove the assets were not used for a crime, the opposite of the general legal requirement for criminal cases. Law enforcement gets to keep 90% of the proceeds it seizes. This incentivizes future acts of asset forfeiture. According to the 2022 Illinois reporting period, 336 of 454 agencies reported receiving funds from asset forfeiture.18 This included $31.2 million in cash and $19.4 million in cash and property that was actually awarded to law enforcement. For reference, Connecticut collected just over $4.7 million. Similarly populous states like Pennsylvania and Ohio collected $24.3 million and $7.5 million. A report on Philadelphia’s civil asset forfeiture scheme shows minorities and the poor are disproportionately more likely to be affected by these programs.19

Illinois scores near the bottom with respect to corruption perceptions. Based on survey data of journalists in states across the country, Illinois tied for seventh worst out of 48 states with data. They scored particularly poorly on legal corruption perceptions, which is the form of corruption that is technically allowed by law but seen as unfair and unjust, such as vast lobbying and political favors. Illinois tied for 42nd out of 48 states. High profile corruption cases drive that, such as former Speaker of the Illinois House of Representatives Mike Madigan, who currently faces a 23-count indictment charging him and a co-defendant with racketeering, conspiracy, bribery and wire fraud.20 Scores on illegal corruption perceptions were no better, also scoring 42nd of out 48 states.

In the final measure of predatory state action, Illinois is the second-most reliant on using fines and fees as a way of raising local government revenue. The most recent data from 2020 showed Illinois raked in over $641 million in fines and fees levied, which averages out to over $50 per person. That’s behind only New York, which took closer to $70 per person. This equates to over $641 million in fines and fees levied in a year. For comparison, Connecticut scored best here, taking just $2 per person.

Education and skills development

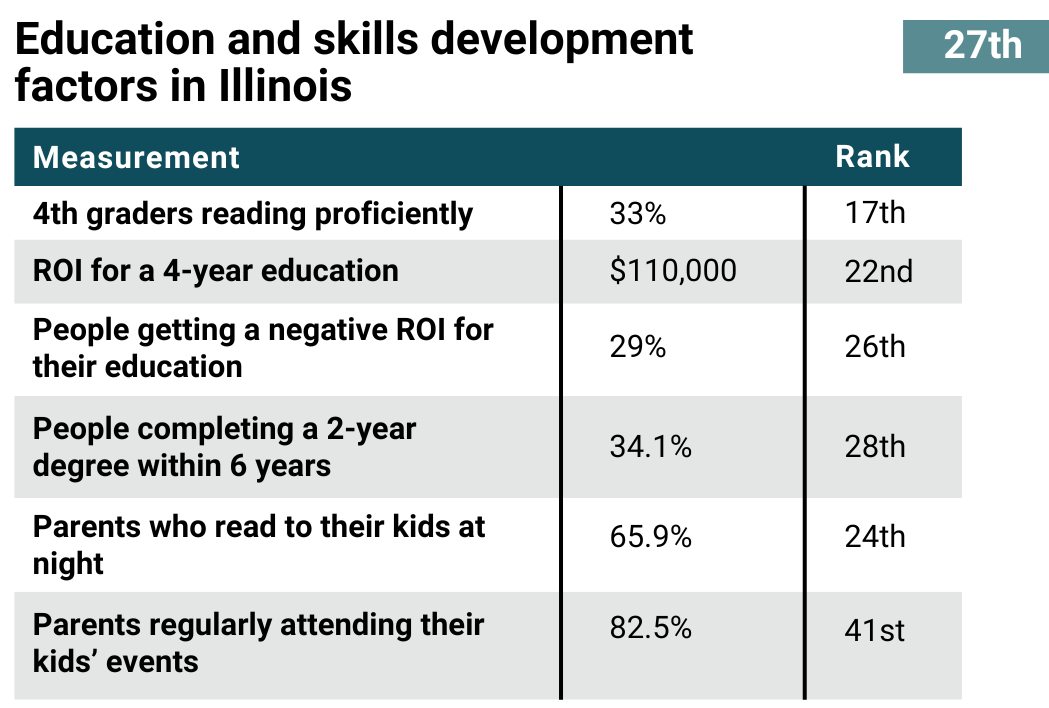

In the third pillar, education and skills development, Illinois ranks much more middle-of-the-pack at 27th. This pillar considers education quality and freedom, where Illinois ranks 12th, and parental engagement and stability, where the state is 34th. As we will see below, the elimination of Illinois’ school choice program – the Invest in Kids Act – will lower the state’s score on education quality and freedom and reduce social mobility.

Illinois’s test scores for fourth and eighth graders on the Nation’s Report Card (NAEP) rank them 10th in the country in reading, which appears promising.21 However, this relative ranking masks deep inequities in Illinois’ educational system. Only 33% of fourth graders performed at or above the NAEP proficient level in reading. Only 15% of Black and 25% of Hispanic fourth graders were at or above proficient in reading.22 The situation is even worse for eighth graders, where only 32% performed at or above proficient. This includes 15% of Blacks scoring proficient, and the number scoring advanced so low it rounds down to zero. 23% of Hispanics were at or above the proficient level in reading.23

Education freedom scores a wide range of policies such as education savings accounts, percentage of students eligible for private school choice, charter school law ranking, scores from the Education Freedom Institute, home-school regulations and reciprocity for teacher certification from other states. School choice is particularly important because research analyzing 187 studies showed school choice improves test scores, educational attainment, parent satisfaction, civic value, racial and ethnic integration, and school safety. School choice also has positive fiscal effects, saving the government money.24

In 2021, Illinois ranked 10th in educational freedom. Illinois currently does not have an education savings account law in place. Previously, 42% of students were eligible for private school choice; charter school law rankings received a D, scoring below average from the Education Freedom Institute. Illinois tied for the top spot on home-school laws, meaning it’s easy for parents to home-school if they choose. Illinois has full reciprocity for out-of-state-teachers to come teach in the state.

In 2023 Illinois eliminated school choice by allowing the Invest in Kids Act to sunset. This law provided 15,000 poor kids, especially minorities, the opportunity to choose a school that meets their needs, even if their family did not have the money. By eliminating school choice for students who most need it, Illinois’ score in this foundational pillar will fall sharply. What’s more, in 2023 alone, eight states expanded school choice: Arkansas, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma and Utah.25 This will boost their score in this area, meaning social mobility in Illinois will fall even further relative to these states.

Illinois’ state universities are not providing a good return on investment for a four-year degree compared to other states. According to the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, the expected return on investment in Illinois is about $112,000 on average. South Dakota’s $217,000 is the highest, nearly double Illinois’. There are 29.9% of Illinois students with a negative return on their degree. This score is much worse than bordering states. For example, only 19.5% of degree holders from Indiana have a negative return; 18.9% have a negative return from Wisconsin; and just one-quarter in Michigan have a negative return.26 Illinois’ scores take a particularly harsh hit in graduation rates at community colleges, where just 34.1% complete a two-year degree in six years or less, which is notably below the average of 37.8%.27

Arguably just as, if not more, important for education and skills development is parental engagement, which has been linked to success for children later in life. Illinois ranks in the middle for the percentage of parents who read to their kids most nights, with 65.9% reporting having done so. For reference, scores range from 46% in Mississippi to 84.3% in Vermont. While their overall response rate is higher, Illinois homes score lower on parental attendance of children’s activities and sharing meals as a household. There were 82.5% who reported attending their kids’ events almost always or mostly. Across the country this ranges from 77% in Hawaii to 92% in North Dakota. Almost three-quarters of parents in Illinois report having dinner as a family most nights of the week, which is slightly below average. Family stability has been found to be crucially important for children’s success. Illinois is in the middle for this category at 34th, which considers the share of births in the last year to unmarried women, as well as the share of households with single parents. This suggests the state of families is not endangered here but has much more room for improvement.

Social capital

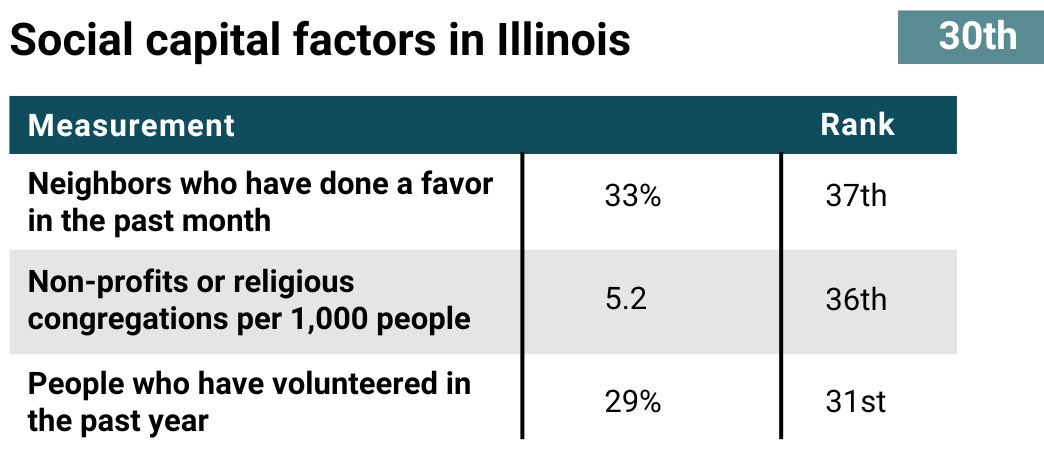

The final pillar of social mobility is social capital. Social capital provides the sort of social and community involvement that can solve more localized, individual issues. Here, Illinois is near the middle, ranking 30th in the nation. Almost across the board, Illinois is right around the average.

With respect to community activities and neighbors, the only indicator that stands out is the percentage of neighbors doing favors in the past month. Just 33% of residents report having done such a favor, which places them very close to the bottom. Utah scores the best here at 51.1%, while Georgia’s 28% puts it in last place. This could perhaps be linked to the outmigration in Illinois, which separates long-time neighbors, making it harder for Illinoisans to have personal connections with one another.

Regarding charity, Illinois is again in the middle. There are just 5.2 non-profit and religious congregations per 1,000 citizens, which puts it much closer to last place Nevada at 2.9 than first place Montana at 10.3. Only 29% of Illinois residents reported volunteering with some group in the past year, once again closer to the bottom, Mississippi at 17.7%, than top-ranked Utah at 46.7%.

Illinois versus other Midwestern states

Illinois’ social mobility ranking in the bottom 10 nationally looks even worse when compared to other Midwestern states. Illinois ranked dead last in the region by a substantial amount. There were four Midwestern states that ranked in the top 10: Minnesota, second; North Dakota, seventh; South Dakota, eighth; and Nebraska, ninth. Two other states, Iowa and Wisconsin, were in the top 15, and Indiana was 21st. Ohio is ranked eight spots higher than Illinois.

Illinois falls flat compared to neighboring states. The silver lining is this analysis makes it clear Illinois truly can improve across these metrics, because other Midwest states do much better.

Illinois is by far the worst-scoring Midwest state for entrepreneurship and growth, where the state is 44th. Many Midwestern states shine here. South Dakota ranks third followed by North Dakota at 11th and Indiana at 14th. Iowa at 33rd and Ohio at 36th were the next closest to the bottom.

Regarding regulations, Illinois was again one of the worst. It scored 32nd, which only beat Minnesota at 33rd and Ohio at 39th. Many neighboring states excelled: Kansas was second, North Dakota was fourth, South Dakota fifth, Indiana sixth, Missouri ninth and Iowa rounded out the top 10.

Relative to the other categories of entrepreneurship and growth, Illinois ranked the worst in taxes and came in last at 46th. South Dakota at third, Missouri at seventh and Indiana at eighth shine in this area. Others such as Ohio and Wisconsin were middle-of-the-pack. Minnesota was just two spots above Illinois and Iowa four spots ahead.

As previously discussed, Illinois ranks low in fostering a dynamic business environment, coming in at 39th nationally. With the exception of South Dakota at 17th and Minnesota at 19th, the Midwest was struggling with business dynamism.

Illinois’ abysmal judicial system and institutional quality look even worse when compared to other Midwestern states. No other neighboring state ranked in the bottom 10. Minnesota and Wisconsin scored in the top 10. Other states such as Indiana and North Dakota were more towards the middle of the rankings.

Illinois lagged other states in education and skills quality, too, with a ranking of 27th. South Dakota and Minnesota were in the top 5, Iowa 6th, and Kansas 10th. Others such as Indiana at 23rd and Ohio at 25th were middle-of-the-road and still ranked higher.

Education quality and freedom was high in Illinois at 12th. But many Midwestern states scored towards the top in the United States in this area: five states – Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota, South Dakota and Wisconsin – were all in the top 10, with Ohio ranking just one spot above Illinois. As discussed above, Illinois’ score will fall noticeably with the elimination of the Invest in Kids Act. Because other Midwestern states such as Indiana, Iowa and Ohio expanded school choice in 2023, their rankings will likely increase while Illinois’ falls.

Social capital in Illinois was second-lowest among Midwestern states at 30th. North Dakota had the top spot in the nation in social capital, with Nebraska at fourth and Iowa at fifth. Minnesota at sixth and South Dakota at seventh were in the top 10. Even states that scored lower than this group were all higher than Illinois, with Wisconsin at 18th, Indiana 21st and Ohio 23rd.

These measures form a blueprint for improving social mobility. Other Midwestern states have better social mobility because they have fewer unnecessary regulations, lower taxes, a fairer judicial system, better education and more social capital. If Illinois focuses on reforms in these areas, which are mostly under the state’s direct or indirect control, it can significantly improve social mobility.

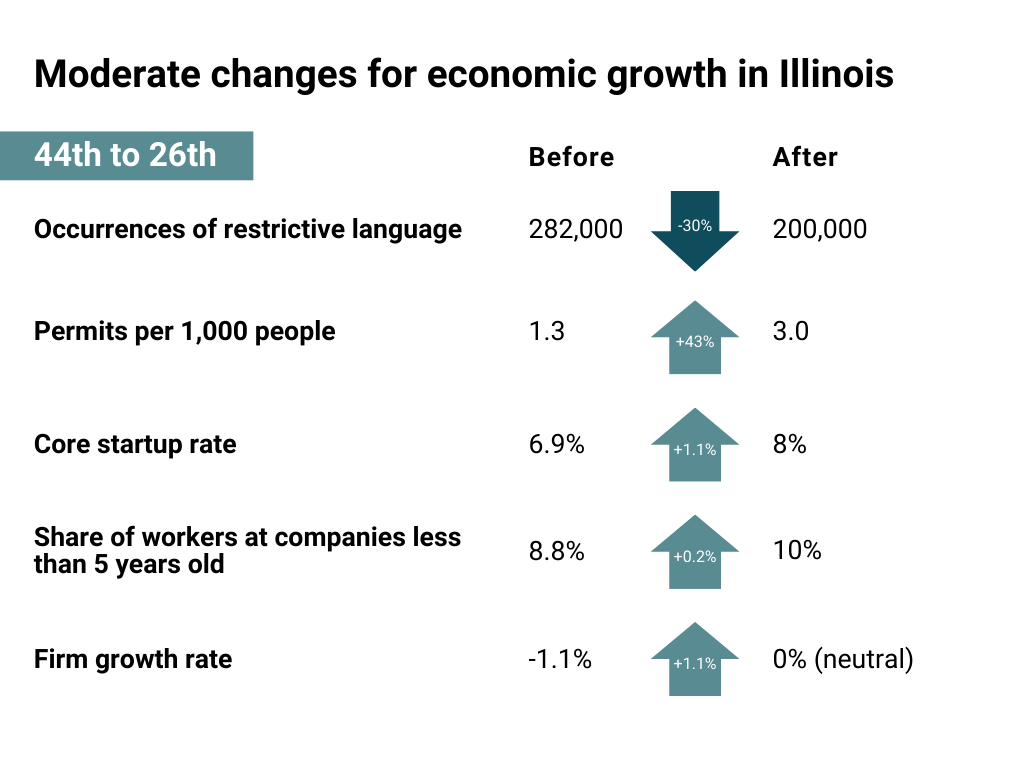

Modest mobility reform proposal: How to get Illinois to No. 25 nationally

With modest reforms, Illinois can achieve middle-of-the-pack social mobility status. These reforms focus on the following:

The environment for entrepreneurship and economic growth is the place to start. Illinois needs to make it easier for businesses and individuals to operate by reducing burdensome overregulation. A 30% reduction in restrictive language would leave Illinois with almost 200,000 such instances, still nearly 50% above the national average of 135,000. The state needs to use already-available mechanisms, and create new ones, to achieve this. The state has some institutions, such as the Joint Committee on Administrative Rules, that could help on this front. The committee has the ability to object to regulations and eventually to introduce resolutions to the General Assembly to prohibit any proposed rule that threatens the public interest, safety or welfare.

Executive branch policies such as a “one-in-two-out” standard would require agencies to eliminate two instances of restrictive language for every one they add. Over time this would significantly reduce restrictive language. A robust sunset review process would review all regulations regularly to make sure they serve an important purpose. If they fail to do so, they’d be eliminated.

Making land use regulations less restrictive would also significantly improve the economic environment by making it easier to build badly needed homes. The bulk of the reforms would need to happen in and around Chicago, where the scores are the worst in the state.

These reforms need to be guided by a proven principle: The key to achieving housing affordability is to increase housing supply. By-right zoning, which means if someone meets requirements for using the property their plan needs to be approved, is an effective means of achieving this. Light-touch density, which allows more units to be constructed on smaller land parcels and includes multi-unit and accessory dwellings such as granny houses, would significantly boost Illinois’ score. We assume modest reforms on this front which would move Illinois from 32nd to 16th for its “regulation” ranking.

Given Illinois’s housing affordability issues, the state needs to focus more attention on increasing supply. Illinois’ permitting process is second worst in the nation. If the state can double the number of permits per 1,000 people, from 1.4 to 3, that would be a significant improvement, and still well below the national average of 4.3 per 1,000.

There are many ways the state can make it easier to get permits. For example, localities can adopt Phoenix’s self-certification model, which allows for registered professionals to certify a project’s compliance with any ordinances and codes associated with buildings, both residential and commercial, to speed approvals. Similarly, New Jersey recently implemented a self-certification program, where architects and engineers can become “qualified design professionals” to ensure compliance with the state’s codes but without developers having to wait for the state’s approval. This will substantially shorten the time needed to build, especially because waiting for permits can be one of the more time-consuming parts of a project. These sorts of reforms would increase the supply of housing, making it more appealing for individuals and businesses to stay in or move to Illinois.

In this modest proposal, we did not alter Illinois’ tax rate, given the political difficulties involved. We will touch more on that in the next section.

Improving its regulation scores would also help Illinois attract business by making it easier for them to start, innovate and grow. While Illinois does not necessarily need its scores to be as good as Indiana in the regulation and tax area, given its advantages in its labor force, and the attractiveness of Chicago, the modest reforms outlined above would be expected to push Illinois up in business dynamism.

If Illinois can move its core startup rate to 8% from 6.9%, this would place the state just above average. This number should rise if they institute the regulatory reforms outlined above. For instance, if Illinois were to install a sunset clause to their regulatory environment, which would allow for unnecessary regulations to be removed after a certain period of time, we would expect to see more businesses open up because they’d face fewer barriers. Research from economists found within the United States, industries that are heavily regulated have fewer new firm starts.28 Similarly, reducing regulations that make it hard to build housing would make it more appealing for someone to move here, or lower the portion of a family’s budget spent on housing. Such reforms would provide workers and would-be entrepreneurs more reasons to move here. If families have more disposable income because their housing costs are lowered, some might use that money to start a business.29

It’s realistic to assume these reforms could increase the share of workers at firms less than five years old up from 8.8% to 10%, getting it to around the average. We can also expect these reforms to get total firm growth at least to a neutral 0%, meaning companies aren’t leaving or closing their doors, from its current negative 1.11%. We can also expect these favorable changes to the business environment to result in more patents. Reducing the regulatory stranglehold would allow for higher gains from innovating. If the patent rate rose to 0.6 per 1,000, it would cause Illinois to rise five spots. Fewer regulations and a stronger entrepreneurial environment should cause innovation to rise slightly, which in turn will increase the number of patents. Research shows areas with more market-oriented economies tend to increase patent activity and specifically patent concentration.

Improvements across this economic pillar, such as the reforms outlined above, can improve Illinois’ dire outmigration rate. Simply getting the migration rate to a stable net-zero level would significantly improve the state’s scores. Tackling regulatory reforms in both the housing and commerce sectors would make it more likely someone would move here for work or other opportunities and would reduce the number of people who leave the state. Sensible reforms can move Illinois’ business dynamism score to 18th from the current 39th. Research shows people move to places with higher levels of economic freedom at the MSA-level; given the link between economic freedom and entrepreneurship, this provides a natural link between less-regulated and more-dynamic economics and its ability to attract citizens.30

Overall, these changes would increase Illinois' ranking in the pillar of “entrepreneurship and economic growth” to 26th, up from 44th, putting it close to Michigan.

Under institutions and rule of law, we propose some modest but important changes. These would have to be done at the local level. Moving fines and fees from $50 a person to just $35 would get Illinois to the average instead of one of the worst in the country. If there are widespread, tangible actions to make corruption reforms a priority, we can expect to see perception scores decrease. For example, changing civil asset forfeiture laws would show signs of trying to reform the judicial process in Illinois, providing more optimism that things are moving in a positive direction.

Given that Illinois’ access to justice score was already good, we don’t recommend ways to improve it.

However, the state is dead last in the quality of the state liability system. Specifically, Chicago and Cook County were seen as the least fair and reasonable litigation environment, with almost 25% of all respondents claiming the area has a poor legal environment. The next closest were Los Angeles at 20% and San Francisco at 19% of respondents viewing those cities as having unfair legal environments.

The state-level liability system scores are based on survey data from in-house general counsels, senior litigators or attorneys, and senior executives at large companies in each state. They specifically are asked questions on aspects of the law such as: treatment of tort and contract litigation, treatment of class-action suits, discovery and evidence, trial judge impartiality and competence, and quality of appellate review. For each individual category, Illinois scored in the bottom three states. They were ranked last for quality of appellate review, trial judge competence, discovery, and treatment of tort and contract litigation. This issue is particularly important for increasing business dynamism in the state, as 89% of respondents reported a state’s litigation environment is “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to influence the willingness to do business in the state.

When prodded further in previous editions of this study, respondents indicated tort reform, timeliness of decisions and eliminating unnecessary lawsuits were particularly onerous areas that could be improved in low-ranking states such as Illinois. Such systems cause injustices to its citizens and make it more costly for businesses to transact in an area. To address this, Illinois could eliminate unnecessary lawsuits to improve their reputation within the state and across the nation. Doing so would provide clarity and optimism that the state will be more friendly to commerce and exchange in the future. Florida has recently undergone similar reforms to their judicial procedures by eliminating one-way attorney fees for all lines of insurance and attorney fee multipliers, protecting small businesses from paying large damages when they are primarily not at fault, and modernizing their ”bad faith” laws to balance between plaintiff attorneys and insurance companies.31 Connecticut’s General Assembly provides another example from a state that has enacted reforms to reduce the number of frivolous lawsuits.32 These reforms would move Illinois from 48th in the country to 31st, between New Jersey and Ohio.

Regarding education and skills development, the state has more work to do since the score in this category will fall because of eliminating school choice. Studies have shown promise in outcomes from school choice policies,xxxiii so we can expect the elimination of the Invest in Kids program to hurt scores. Reinstating or expanding the program would increase test scores. Given the lack of direct state control of parental engagement and stable families, we did not adjust these scores.

Under “social capital” we only modestly addressed charity regulation, which is under the most direct state control. Currently, they have some of the strictest scores in terms of audit requirements. Any charity with revenue of $300,000 or more must have an audit performed.34 There are 24 states that do not require an independent CPA audit. Such a low bar for requiring audits adds unnecessary costs to charities and makes it harder for them to start. It also forces them to shift resources from care to compliance. Simply following these 24 states and removing the CPA audit would increase Illinois’ score significantly, moving the state well into the top half of all states.

Overall, this slate of reforms gets Illinois to 26th in the country, which is just five spots below Indiana and up from 40th, an attainable goal for getting Illinois to the middle of the pack.

Becoming a social mobility leader

In this section, we show how Illinois can become a leader in social mobility, with the goal of getting the state into the top 10. We note that doing so involves not only state policy, but also fundamental changes from Illinoisans.

We now suggest more significant measures for each of the pillars, including additional changes to what we reformed above. These reforms focus on the following:

Again, starting with entrepreneurship and economic growth, we note Illinois has the infrastructure and highly capable labor force necessary to move up the ranks.

With regulation, we recommend some dramatic changes in occupational licensing. We suggest cutting barriers and licenses down to get Illinois to the top 3 in least restrictive licensing codes. There are many low-hanging fruit professions such as community association manager or cemetery customer service employee who shouldn’t require an occupational license.

Infusing the state’s sunset review process with vigor is a simple way to get rid of unnecessary licensing. By putting into place a sunset review process, there is a more realistic avenue to assess the relative benefits and costs associated with each license. In its current process, there is a disproportionate incentive for practitioners to reduce competition. Putting this decision-making process in the hands of those who do not directly benefit from stifling new entrants can allow for broader societal factors to be considered.

If Illinois were to also reduce regulatory stringency to 150,000 instances – the average is 135,000, so still well above average – from 282,000, the state would improve its regulation ranking from 32nd to ninth, just above Missouri.

The Mercatus Center’s snapshot of regulations in Illinois provides some key industries where Illinois is exceptionally stringent.35 Their report reveals waste management and remediation services have over 18,000 restrictive terms used, compared to the average of 7,300 across all states. Chemical manufacturing sits at 15,000 restrictive words, compared to an average of less than 7,000 across states. Perhaps most important are in terms of food and beverage stores, as Chicago is an area people visit often. Food and beverage stores have 9,000 restrictive words, more than half of the 4,464 average. Cutting these to just the average across states would make great headway in establishing Illinois an area primed for more business activity and economic mobility.

While set aside in the previous section, Illinois must reform its tax code to really maximize its social mobility potential. We suggest modest reforms that would still have Illinois rank near the middle, but substantially up from where it is now at 46th. With respect to corporate taxes, Illinois could follow Nevada’s example. Nevada does not have a corporate tax but does have a state gross receipt tax of 6.85%. Sales tax rates would move from 8.85% to 7% to be closer to neighbor Indiana.

Property taxes are where Illinois ranks particularly poorly. As of 2023 the rate was 1.95% of a home’s value paid in taxes each year. Moving closer to the middle would involve mirroring the tax rate of a state such as Georgia at 0.72%.36 Doing so moves Illinois all the way up to 21st in this pillar.

These reforms will help with business dynamism. We can expect a modest increase in the rate of startups, from 8 to 9%, its share of workers in young firms to 11% and growth in total firms to 0.5%. We kept housing permits and patents at the same rate as in the previous section, but now moved its reallocation rate, which measures the rate at which individuals change jobs, from 22.2% to 25%. If regulation and tax systems are reformed, then one would expect new firms to be created in the state, providing more opportunities for people to change careers and help spread ideas and best practices. These reforms will make it easier to work. Under favorable circumstances, the labor force participation rate would increase to 66%, putting Illinois in the top half. As of May 2024, Illinois’ labor force participation rate was 64.9%, meaning it has started to close the gap on this important metric.37

With a much more favorable economic environment, we can expect more people to move to Illinois. We assume a modest positive net migration of 0.5%.

These reforms overall would be expected to improve Illinois’ business dynamism score to 11th in the country,

Overall, these reforms increased Illinois’ “entrepreneurship and economic growth” ranking to eighth, up from 26th in the previous section and well up from 44th in the original index.

Under predatory state action, we recognize even with such reforms, it takes time to rebuild trust in the judicial system. One area where the state can focus that would have a real impact is civil asset forfeiture. If the state were to move to the middle of the pack with less abusive practices, it could move its ranking in “institutions and rule of law” up to 24th. Illinois scores particularly low in penalties for failing to file a forfeiture report, which makes excessive use less likely to be caught. Furthermore, law enforcement agencies can keep up to 90% of the assets seized, providing a large incentive to continue this practice; however, doing so allows for misuse and excessive extraction of assets to continue. Illinois also places the burden on the owner of the property to prove that it was not used for a crime. Simply reforming these three aspects will improve community trust in law enforcement, disincentivize overuse of this practice and lower the probability the poor will be targeted in civil asset forfeiture.

The best way for Illinois to significantly improve its ranking in “education and skills development” is to reinstate and expand school choice. This expansion is happening across the nation, and Illinois would see many benefits from joining the trend. Because Illinois just eliminated school choice, we recognize the low odds this policy will be changed.

We also altered the scores for return on investment of university attendance, which we believe are reasonable given the other changes we suggested. The benefit one achieves after graduation has as much to do with the conditions of the state they work in as it does with the quality and cost of the university itself. Providing a more dynamic labor environment, as outlined in the section on entrepreneurship and growth, will mean university attendees can stay in the state. Such a labor market would provide easier access to jobs, which raises incomes.

The Foundation for Research and Equal Opportunity provides three suggestions for higher education reform, which if adopted by Illinois could improve its students’ return on investment.38 Two of them are particularly important for this pillar. The first is outcome-based funding grounded in student achievement. Indiana and Ohio are leading states in this regard, while Illinois has some of the lowest outcome-based funding in the country. Another potentially more radical approach is state authorization reform. In this report, the foundation shows enrollment was over 13.8 million nationwide, an increase of over 33% since 1990. However, there is virtually no uptick in the number of degree-granting nonprofit colleges during the same time. Given this mismatch, they claim new universities have heavy barriers to entry. More competition in this market can provide lower tuition, because an increase in supply lowers prices. Competition would also provide different avenues of specialization within universities.

Illinois has the benefit of some of the most recognized universities in the country, such as the University of Chicago, Northwestern University and Loyola University-Chicago. Some of these suggestions would provide even more opportunity for those universities and others in the state. Better access to job opportunities would raise students’ return on investment scores.

We expect a modest increase in median return on investment from $112,000 to $150,000 to result from these changes, putting it closer to Michigan, a similar state. The percentage of students with a negative return on investment in a college degree would decrease. We estimate a modest decrease from 29.9% to 25%, again, around the same score as Michigan. This moved Illinois’ “educational quality and freedom” score up to fourth.

For “parental engagement and stability,” we note state policies can have only indirect effects on such variables. States with more opportunities allow parents to choose career prospects with more variety, allowing them to spend more time with their children. A work environment more conducive to engaged parenting would allow more parents to attend children’s activities and share meals in a household. A modest increase would mean 86% of parents attend most of their children’s events, up from 82.5%, and 76% share most meals together as a household, up from 74%. Still, the onus of this change is really on families and individuals. It takes a village.

Similarly, policies can indirectly affect family structure and stability. Tough working conditions incentivize families to split apart in pursuit of higher benefits granted to separated families. When there are incentives to not be married, individuals on the margin of those benefits will often choose to be separate to receive those added benefits.

Illinois can empower more people to follow the “success sequence,” which would improve family stability. According to Ron Haskins and Isabell Sawhill, Brookings Institution scholars who popularized the term, it describes “what young people need to do and when they need to do it” to ensure they are not in poverty and experience more opportunity. “First comes education... Then comes a stable job that pays a decent wage, made decent by the addition of wage supplements and work supports if necessary. Finally comes marriage, followed by children.”39 Haskins’ later refined version of the sequence is: “at least finish high school, get a full-time job and wait until age 21 to get married and have children.” Of American adults who did this, only about 2% were in poverty and about 75% joined the middle class.40 The “success sequence” is a proven pathway to opportunity and is widely accepted across the ideological spectrum.

In addition to being a general pathway to opportunity, this sequence results in stronger families because there are fewer challenges to staying intact. Illinois can indirectly promote the success sequence by empowering people through a strong education system focused on career preparedness and by creating an economic environment with good jobs available.

Because there are not things the state can directly do to improve this pillar, we do not alter these scores.

Overall, these changes would bring Illinois’ ranking on “education quality and skills development” up to 12th in the country from 27th.

In social capital, there are some potential indirect effects from government action. As government policies push people out of the state, communities are hurt. Areas that were once strong and familiar with each other are now broken, a little or a lot depending on the degree of outmigration. This leaves people less familiar with one another. We rely on the changes in this index coming from mostly individualized changes, meaning citizens in the state must also do the leg work to get Illinois to the top 10.

Modest improvements in Illinois in the areas of community activities and neighbors would make a big difference to social mobility: percent attending an event based in the community increases from 13.9% to 15%; member organizations per 1,000 increases from 2 to 2.5; percent of neighbors doing favors for one another from 32.8% to 36.6%; and economic connectedness from 0.84 to 1. These improvements would move Illinois’ ranking in this subarea to 30th.

We similarly assume modest changes to charity: non-profit organizations and congregations per 1,000 increases from 5.2 to 5.9, the average, and percent who volunteered with a group in the past year goes up from 29.2% to 33%. Given the previous adjustments to the charity regulation section, we would expect a marginal improvement in the number of charities in the state, leading to the increase in non-profit organizations. Improvements in the labor market provide more flexibility, which can allow for more volunteer activity to take place.

With community activities and charity, there are no levers the state can pull to improve this directly. Indirect ways to address this include reversing outmigration by creating a state where people want to move. Outmigration breaks down communities.

These changes move the social capital score up to 15th in the country. Overall, these changes give Illinois a social mobility index score placing them in the top 10. Of all bordering states, they would now be at the top, rather than the bottom. This would have Illinois ahead of all nearby Midwestern states, except for Minnesota. While this transformation involves a lot of work, it is well within reach.

Conclusion

For over two centuries, the promise of America has been social mobility and opportunity. Today, Illinois is falling short of that promise. Tomorrow can be better.

In this report we’ve outlined both a modest and more ambitious reform agenda to empower Illinoisans across the state to unleash their potential and create thriving communities. Many of the changes simply require Illinois to move up from near the bottom to the middle of the pack.

Top areas for reform include making housing affordable, reducing the number of harmful regulations constraining individuals and businesses, putting into place a more reasonable litigation environment and reinstating Invest in Kids to allow families choices about their children’s schools.

Illinois’ elected officials face a choice: Will they commit to making Illinois a place where families want to move, call home, and grow? Will Illinois become a place with a booming economy, thriving communities and empowered individuals? Or will it continue to be a place where each year tens of thousands of families flee because they don’t see a future in the state?

Illinois’ problems are man-made. We can fix them. This report provides a reform agenda for doing precisely that, with its focus on restoring the American Dream for all Illinoisans.

Endnotes

1 “Global Social Mobility Index 2020,” World Economic Forum, January 19, 2020, https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-social-mobility-index-2020-why-economies-benefit-from-fixing-inequality/.

2 Justin T. Callais and Gonzalo Schwarz, “Social Mobility in the 50 States,” Archbridge Institute, December 18, 2024, https://www.archbridgeinstitute.org/social-mobility-in-the-50-states/.

3 “WSJ/NORC Poll October 2023,” WSJ/NORC, November 20, 2023, https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/documents/WSJ_NORC_Partial_Oct_2023.pdf.

4 Jared Sousa, “American Dream Far From Reality for Most People: POLL,” ABC News, January 15, 2024, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/american-dream-reality-people-poll/story?id=106339566.

5 Gabriel Borelli, “Americans Are Split Over the State of the American Dream,” Pew Research Center, July 2, 2024, https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/07/02/americans-are-split-over-the-state-of-the-american-dream/.

6 Gonzalo Schwarz, “American Dream 2024 Snapshot: The Health and State of the American Dream,” Archbridge Institute, August 28, 2024, https://www.archbridgeinstitute.org/american-dream-snapshot/.

7 Callais and Schwarz, “Social Mobility,” Archbridge Institute.

8 Dustin Chambers and Patrick McLaughlin, “Illinois’ Regulatory Landscape,” Mercatus Center, August 2024, https://www.mercatus.org/regsnapshots24/illinois.

9 Edward Timmons and Noah Trudeau, “State Occupational Licensing Index,” Archbridge Institute, March 20, 2023, https://www.archbridgeinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/2023-State-Occupational-Licensing-Index.pdf.

Note that higher scores in the original report corresponded to worse licensing score, but in the Social Mobility Report, this score was inverted (10 minus original score) so that higher scores correspond to more mobility in this space. For example, in the original report, Illinois received a score of 4.13 on licenses and 2.15 on barriers.

10 Morris M. Kleiner, “Reforming Occupational Licensing Policies,” The Hamilton Project Discussion Paper 2015-01, January 27, 2015, https://www.hamiltonproject.org/publication/policy-proposal/reforming-occupational-licensing-policies/, p. 6.

11 “Economy at a Glance: Illinois,” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, November 14, 2024, https://www.bls.gov/eag/eag.il.htm.

12 Darwyyn Deyo et al., License to Work: A National Study of Burdens from Occupational Licensing, Institute for Justice, November 29, 2022, 3rd ed., https://ij.org/report/license-to-work-3/, p. 23-24.

13 Josh Bandoch and Joe Tabor, “Regulatory Reform Can Make Housing More Affordable for Illinois Families,” Illinois Policy Institute, July 15, 2024, https://www.illinoispolicy.org/reports/regulatory-reform-can-make-housing-more-affordable-for-illinois-families/, p. 9.

14 Id., p. 19.

15 “Freedom in the 50 States: An Index of Personal and Economic Freedom,” Cato Institute, November 30, 2023, https://www.freedominthe50states.org/land-use.

16 Steven Vance, “Apartments & Condos Are Banned in Most of Chicago,” Medium, May 14, 2019, https://blog.chicagocityscape.com/how-much-of-chicago-bans-apartments-b6c5b68db2fb.

17 Bryce Hill, “Census: 97% of Illinoisans Moving Out Head to Lower-Tax States,” Illinois Policy Institute, November 1, 2023, https://www.illinoispolicy.org/census-97-of-illinoisans-moving-out-head-to-lower-tax-states/.

18 “2022 Illinois Seizure and Awarded Assets Annual Report ,” Illinois State Police, April 20, 2023,

https://isp.illinois.gov/StaticFiles/docs/AssetSiezure/2023/2022%20Annual%20Report%20Summery.pdf.

19 Jennifer McDonald and Dick M. Carpenter, “Frustrating, Corrupt, Unfair: Civil Forfeiture in the Words of Its Victims,” Institute for Justice, October 2021,

20 Todd Feurer, Sabrina Franza, and Marissa Perlman, “Corruption Trial of Longtime Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan Begins,” CBS News, October 21, 2024, https://www.cbsnews.com/chicago/news/opening-statements-corruption-trial-mike-madigan/.

21 “State Performance Compared to the Nation,” The Nation’s Report Card, 2022, https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/profiles/stateprofile?sfj=NP&chort=1&sub=MAT&sj=&st=MN&year=2022R3.

22 “2022 Reading Snapshot Report: Illinois Grade 4,” The Nation’s Report Card, 2022, https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/subject/publications/stt2022/pdf/2023010IL4.pdf.

23 “2022 Reading Snapshot Report: Illinois Grade 8,” The Nation’s Report Card, https://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/subject/publications/stt2022/pdf/2023010IL8.pdf.

24 “123s of School Choice 2023 Edition,” EdChoice, 2023, https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/123s-of-School-Choice-WEB-07-10-23.pdf.

25 Tom Greene, “How 8 States Expanded School Choice to Nearly All K-12 Families in 2023,” ExcelinEd In Action, January 10, 2024, https://excelinedinaction.org/2024/01/10/from-policy-to-action-how-8-states-expanded-school-choice-to-all-k-12-families-in-2023/.

26 Preston Cooper, “Ranking the 50 State Public University Systems on Prices & Outcomes,” FREOPP, December 12, 2022, https://freopp.org/whitepapers/ranking-the-50-state-public-university-systems-on-prices-outcomes/.

27 “Graduation and Retention Rates: What Is the Graduation Rate within 150% of Normal Time at 2-Year Postsecondary Institutions?,” National Center for Education Statistics, 2022, https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/TrendGenerator/app/trend-table/7/21?trending=column&rid=6.

28 James B. Bailey and Diana W. Thomas, “Regulating Away Competition: The Effect of Regulation on Entrepreneurship and Employment,” Journal of Regulatory Economics 52, no. 3 (October 25, 2017): 237–54, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11149-017-9343-9.

29 Jamie Bologna Pavlik and Gary A. Wagner, “Patent Intensity and Concentration: The Effect of Institutional Quality on MSA Patent Activity,” Papers in Regional Science 99, no. 4 (August 2020): 857–99, https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12515.

30 Imran Arif et al., “Economic Freedom and Migration: A Metro Area‐Level Analysis,” Southern Economic Journal 87, no. 1 (May 5, 2020): 170–90, https://doi.org/10.1002/soej.12437.

Daniel L. Bennett, “Local Institutional Heterogeneity & Firm Dynamism: Decomposing the Metropolitan Economic Freedom Index,” Small Business Economics 57, no. 1 (January 27, 2020): 493–511, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00322-2.

31 “Governor Ron DeSantis Announces Comprehensive Lawsuit Reforms to Protect Floridians from Predatory Billboard Attorneys,” Bay County News, February 14, 2023, https://www.flgov.com/2023/02/14/governor-ron-desantis-announces-comprehensive-lawsuit-reforms-to-protect-floridians-from-predatory-billboard-attorneys/.

32 Sandra Norman-Eady, “Remedies for Frivolous Lawsuits,” OLR Research Report, October 10, 2023, https://www.cga.ct.gov/PS98/rpt%5Colr%5Chtm/98-R-0916.htm.

33 Anna J. Egalite and Patrick J. Wolf, “A Review of the Empirical Research on Private School Choice,” Peabody Journal of Education 91, no. 4 (June 29, 2016): 441–54, https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956x.2016.1207436.

34 Wayne Winegarden, “The 50-State Index of Charity Regulations,” Philanthropy Roundtable, January 31, 2023, https://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/resource/the-50-state-index-of-charity-regulations/#data-appendix-d, Appendix D.

35 Chambers and McLaughlin, “Illinois’ Regulatory Landscape.”

36 Andrey Yushkov, “Where Do People Pay the Most in Property Taxes?,” Tax Foundation, August 20, 2024, https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/state/property-taxes-by-state-county-2024/.

37 “Labor Force Participation Rate for Illinois,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, October 22, 2024, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LBSSA17.

38 Annie Bowers and Preston Cooper, “Three Ways States Can Lead on Higher Education Reform,” FREOPP, October 4, 2024, https://freopp.org/whitepapers/three-ways-states-can-lead-on-higher-education-reform/.

39 Ron Haskins and Isabell Sawhill, Creating an Opportunity Society (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institute Press, 2009), p. 15.

40 Ron Haskins, “Three Simple Rules Poor Teens Should Follow to Join the Middle Class,” Brookings Institution, March 13, 2013, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/three-simple-rules-poor-teens-should-follow-to-join-the-middle-class/.