Illinois can spend another $10B on infrastructure without tax hikes

By Adam Schuster

Drivers need not travel far to understand Illinois’ roads and bridges need work, but just try to find someone willing to pay more for those improvements and repairs at a filling station.

That is, unless the filling station is in Springfield. Lawmakers in the state capital seem to be focused on only one question regarding construction spending in Illinois: how do we pay for it? The only answer they’ve come up with so far is to take more money from overtaxed drivers.

Absent from the conversation are reforms to maximize the economic benefits of infrastructure spending and ensure taxpayers get value for what they already pay.

There are much better ways to build up Illinois, and without gas tax or vehicle fee increases. Those ways require lawmakers to be smart about how and when they spend infrastructure dollars to get the most return for taxpayers’ investments. They require the political will to stop buying votes with pork projects.

If state leaders listen to the experts and learn from other states, the following principles should guide the effort to rebuild Illinois:

- With details on a federal capital plan still in the works and at this point in the economic cycle, capital spending should focus on maintenance infrastructure rather than expansive new projects

- Illinois should reform costly prevailing wage mandates and adopt an evidence-based, data-driven project selection process to maximize return on investment

- Common-sense savings reforms coupled with dedicating revenues to transportation from legalized sports betting and sales taxes on gasoline would enable the state to fund its most needed capital projects without economically harmful tax and fee hikes on drivers

Spending legislation focused on improving Illinois’ infrastructure, known as a capital bill, is a core component of Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s legislative agenda. Pritzker campaigned on a “comprehensive 21st Century Capital Bill,” including ambitious new projects such as statewide high-speed broadband.

Capital or infrastructure spending in Illinois refers to how the state pays for repairs and new construction on roads, bridges, government buildings and other structures such as water treatment plants. The governor is required to present a capital plan to the General Assembly detailing available revenue from transportation-related fees and taxes, as well as a plan for how to invest them. This is separate from the general revenue or operating budget proposal that typically gets most of the attention.

Illinois has not had a major new capital program since 2009, the $31 billion Illinois Jobs Now! Plan.

A new plan is needed, but with all of Illinois’ fiscal challenges it cannot just be the same old plan that leans hard on taxpayers and then squanders their money.

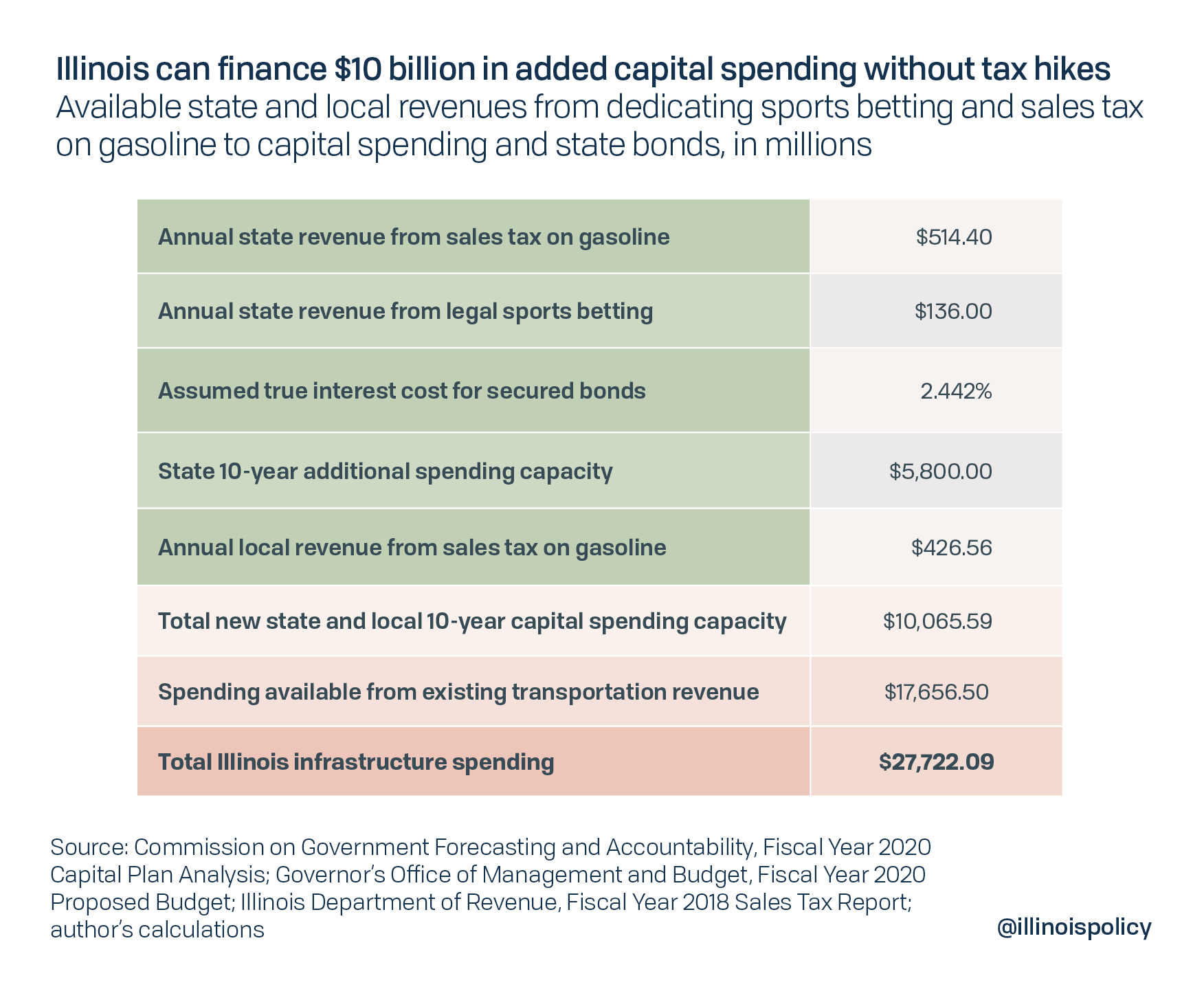

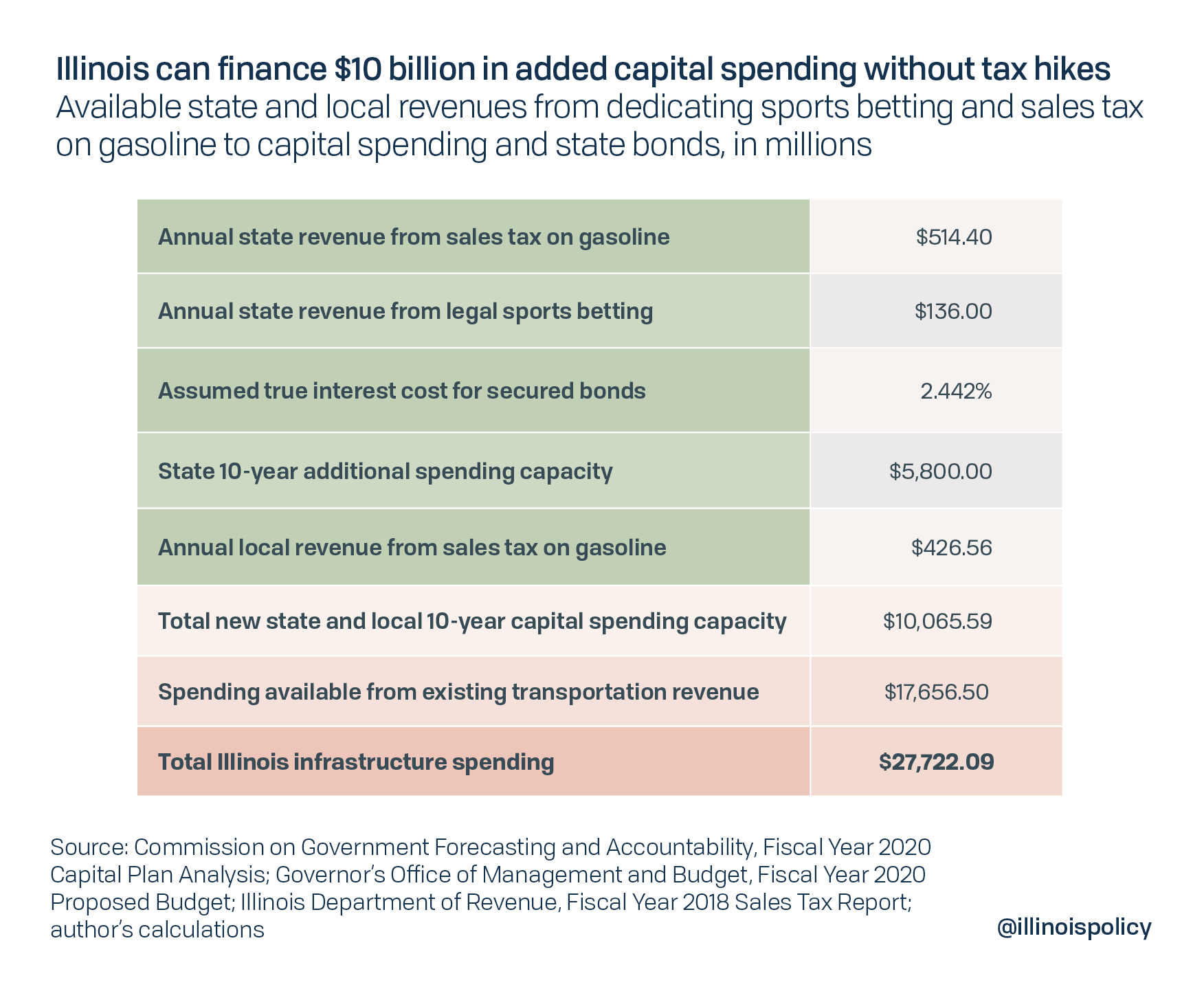

Without raising taxes, Illinois can add $10 billion in new capital spending over 10 years. Total state and local spending on infrastructure can reach nearly $28 billion if coupled with reforms and combined with existing resources and capacity reflected in the governor’s proposed fiscal year 2020 capital budget. Again, that’s without raising taxes.

The first priority should be taking care of what Illinois already has.

Before pursuing new projects, lawmakers should wait for federal assistance and for an economic downturn, when costs drop and the Illinois economy will most benefit from a public spending boost. Federal assistance looks increasingly more likely with President Donald Trump and Democratic leadership in Congress recently reaching an agreement in principle to pursue a $2 trillion federal infrastructure plan, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Advocates of a capital bill are correct that transportation infrastructure is of critical importance to Illinois’ economy and the quality of life of its residents. But without reform and thoughtful project selection, a capital plan could easily become a vehicle for wasteful spending, political favoritism and more tax hikes that fail to provide value to Illinois residents while harming the state’s struggling economy.

The case for patience and restraint in infrastructure spending

Many advocates for a capital bill in Illinois argue in favor of tens of billions of dollars in new spending, including expensive new projects. In a 2018 email to the Civic Federation, a Chicago-based think tank, the Illinois Department of Transportation, or IDOT, argued for a $1.7 billion annual increase in maintenance infrastructure spending and a $2.25 billion annual increase for new projects. IDOT’s figures suggest a capital plan of nearly $40 billion over a typical 10-year period for bond repayment. Similarly, the Metropolitan Planning Council has argued for $43 billion in spending over 10 years.

Commonly, those arguing in favor of the most expansive capital plans – along with tax and fee hikes to fund them – stand to benefit financially. This includes IDOT, the International Union of Operating Engineers Local 150, whose members would work on roads and other projects, and Build Up Illinois, a coalition of hospitals, schools, colleges and labor unions who benefit from building construction.

However, expert research does not support the idea that expansive new construction will substantially benefit Illinois’ economy right now. And lawmakers must ensure that a capital plan does not become a bloated and politically motivated handout to self-interested lobbyists.

Illinois should focus on maintenance infrastructure rather than new construction

In most cases, maintenance infrastructure has a better economic return on investment compared to spending on new projects, according to peer-reviewed academic economics literature.1 The reason is that maintenance infrastructure – such as repairs and upkeep on existing roads, bridges, airports and dams – prevents damage to private-sector investments and therefore increases the firms’ return on capital investment. For example, a trucking company is likely to make more productive use of a new fleet of trucks if they do not have to regularly repair damage from potholes.

Economist Jeffrey Dorfman, writing for Forbes, argued the next federal infrastructure plan should include no new infrastructure at all. Dorfman argues a focus on improvements and repairs limits the risk of politicians wasting money on unnecessary projects that have a poor return on investment.

Even proponents of new project spending acknowledge the case is stronger for maintenance infrastructure, as seen in a recent forum hosted by the Hutchins Center, a project of the non-partisan research Brookings Institution. Larry Summers, Harvard economist and former economics advisor to Presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton, argued that there is an “overwhelming case” for expanded spending on maintenance infrastructure while acknowledging the case for new projects was “more speculative.”

Another Harvard economist, Ed Glaeser, argued in the forum that maintenance infrastructure has a higher return on investment in large part because projects will naturally be focused on infrastructure that is most used by the public and therefore in the most need of repair, echoing comments by Dorfman in Forbes. However, political forces push new projects that get more press and attention. As Glaeser put it, “Nobody ever named a maintenance project…”

To deliver value for Illinois residents and drivers, lawmakers must resist the urge to fund a wish list of new projects. They must focus on a more limited plan to repair existing roads, bridges and facilities.

Illinois should not go it alone in the 11th year of an economic expansion

The federal government has historically been an important partner in major state and local capital planning.

The federal government funded 86% of state and local capital spending from 2005 to 2014, according to the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Additionally, the federal government typically matches state spending on interstate highways at a rate of 90% and on other roads and highways at 80%.

With President Trump and congressional Democrats working together on a potential $2 trillion federal infrastructure plan, Illinois lawmakers should wait until those details are finalized. They should not pursue more expansive infrastructure spending on their own that includes new projects, rather than maintenance. By exercising patience, lawmakers can maximize federal matching grants so less of the burden is borne by Illinois’ financially strapped state and local governments, as well as the overburdened taxpayers who fund them.

While details of the federal plan are still not final, the Trump administration has suggested prioritizing federal matching grants for states that create new dedicated revenue streams for capital spending. Federal transportation advocacy groups, including Transportation for America, have long suggested a federal matching grant formula that prioritizes maintenance costs.

Illinois lawmakers risk leaving federal matching dollars on the table by acting now. By limiting state action to more modest maintenance spending that’s within the state’s current capacity, lawmakers give the state more flexibility to structure additional capital spending in the future.

Additionally, economics literature suggests now is the wrong time for Illinois to advance expansive new capital spending. Peer-reviewed academic research has found that economic stimulus benefits are maximized when governments spend on capital improvements during a recession or financial crisis, when private-sector demand in the economy is low. Government spending is less likely to crowd out private investment during such downturns.2

The U.S. economy is in the 11th year of an economic expansion, and the National Highway Construction Cost Index, which measures the cost of building projects, is at its highest level since 2008.

Cross-national economics research has also found that government spending stimulates economies less when debt burdens are high. It may even have a negative return on investment in high-debt countries.3 High debt burdens combined with new spending send a signal to residents and businesses that taxes will be higher in the future, crowding out private sector investments. Illinois’ debt burden at $50,800 per taxpayer is the third-highest in the nation, according to Truth in Accounting.

Illinois must invest in maintenance infrastructure now to prevent damage to roads and bridges that could be more costly to repair in the long run, as well as to prevent harm to Illinois motorists. The case for more expansive capital spending would be stronger during an economic downturn, when Illinois has made necessary spending reforms to reduce its debt burden, and when the federal government has finalized its own capital program.

Limiting political influence, easing costly mandates will ensure a good return on investment

There are credible concerns that Pritzker’s administration hopes to trade capital projects for votes on his plan to scrap Illinois’ constitutionally protected flat tax and make way for a state income tax hike. Not only is it wrong to hold infrastructure spending hostage to force through an economically harmful tax hike, but taxpayers will get far less value from a capital bill if projects are selected for political reasons rather than based on a neutral cost-benefit analysis.

Before adopting a capital bill, lawmakers should implement controls to ensure spending goes first to needed projects. They should make reforms to ensure the money is spent as efficiently as possible.

Data-driven project selection, not pork

As recently reported by the Chicago Tribune, capital projects in Illinois are often used as a political vote-buying mechanism to earn support for unrelated legislation. By “bringing home the bacon,” lawmakers hope to earn support for reelection, which is where the term ‘pork barrel spending’ comes from. Improvements or new construction for buildings, roads and bridges in lawmaker districts are highly visible to voters and likely to be rewarded.

When politics determines capital spending, projects can be granted or withheld by party leaders as leverage for support on controversial issues that might not otherwise pass. The Chicago Tribune reported that state Rep. Jay Hoffman, D-Swansea, recently acknowledged this form of horse trading explicitly, saying, “A capital bill is helpful for people being able to take votes so they can show that these (other) votes were worth it for their district.” Hoffman is assistant House leader under House Speaker Michael Madigan and a former House Transportation Committee chairman.

Even without a comprehensive capital plan, pork projects are commonplace in the Prairie State. The Illinois Policy Institute identified $27 million of pork-barrel spending projects in the fiscal year 2019 state spending plan, including $10 million for the privately owned Uptown Theater in Chicago. The last major new capital plan, Illinois Jobs Now!, included wasteful projects such as $670,000 for copper-plated doors and $500,000 for chandeliers and sculptures, both for the Illinois Capitol building in Springfield.

To prevent political influence over capital spending and to ensure a good return on investment for taxpayers, Illinois should adopt a comprehensive capital improvement plan that includes a data-driven cost benefit analysis. The Civic Federation, a Chicago-based think tank, has long advocated for such a system in Illinois.

According to the Government Finance Officers Association, best practices in capital planning include multi-year evaluations of funding capacity, ongoing monitoring and oversight provisions, and significant commitments to maintenance infrastructure.

Lawmakers should look to adopt a system similar to Virginia’s Smart Scale for project selection. State law requires Virginia to use an “objective and quantifiable” prioritization process for project selection that takes into account the cost and benefits of infrastructure spending. Factors include congestion mitigation, safety, accessibility, economic development and effects on the environment. The Smart Scale then assigns a specific score to each proposed project and ranks them relative to other potential projects.

Jeffery C. Southard, executive vice president of the Virginia Transportation Construction Alliance, argued in an article published by the Richmond Times-Dispatch that the Smart Scale has improved Virginia’s allocation of infrastructure dollars and enhanced the “quality of life for all Virginians.”

Ideally, Illinois should apply this data-driven project selection to all construction, not just for transportation projects as in Virginia. However, transportation infrastructure should be prioritized. Vertical construction projects should be funded only if lack of action poses an imminent threat to state residents and employees, or if inaction would cause an interruption in core government systems. The harm of structurally unsound bridges or badly damaged roads far outweighs the fact that carpeting in the Thompson Center is held together with duct tape, for example.

Adopting such a system in Illinois would maximize return on investment as well as transparency, to give residents more faith that politics are not driving project selection. If politicians continued to select projects for political reasons after adopting a Smart Scale, residents across Illinois would better see when they misused infrastructure dollars.

Reforming or eliminating prevailing wage mandates

Illinois’ prevailing wage law, which mandates industry-specific minimum wages for public construction that vary by county, drives up the cost of construction for taxpayers. In practice, prevailing wage rates are determined by local collective bargaining agreements negotiated by private sector unions.4

On average, labor costs account for 20 to 30 percent of the total cost for construction projects and the average prevailing wage rate in Illinois is 40% higher than the average wage for private construction jobs in the same area.

Fully repealing Illinois’ prevailing wage law and allowing true competitive bidding on construction projects would save taxpayers an average of 10% on public construction costs. This reform would enable each dollar Illinois spends on infrastructure to go farther.

Short of full repeal, lawmakers could give taxpayers more for their money by adopting thresholds for when prevailing wage mandates apply. Of the 27 states with this type of public construction labor mandate, Illinois is one of only eight that apply the law to all construction regardless of size and cost.

For example, Connecticut’s prevailing wage law only kicks in if a project’s cost exceeds $400,000 for new construction or $100,000 for remodeling.

Adopting thresholds for prevailing wage would enable local governments in Illinois to competitively bid smaller construction projects such as additions to schools or minor road work. They could contract services for the lowest possible cost. Full repeal would maximize spending efficiency even more.

More tax hikes on a struggling state economy are the wrong way to fund capital spending

For advocates of increasing taxes and fees on drivers, there are two main ideas: a vehicle miles traveled tax, or VMT, and increases in traditional sources of transportation funding, such as the motor-fuel tax or registration fees. Both options would raise the cost of owning and using a vehicle.

Illinois already has one of the highest state and local tax burdens in the nation. High taxes are the No. 1 reason people say they want to leave, and given the state’s five straight years of population loss, it cannot afford to alienate more residents.

Proponents of making drivers pay more miss the mark

An attempt to introduce a VMT per-mile tax, House Bill 2864, was defeated in Springfield earlier this year. Proponents say a VMT would be a better way to fund infrastructure because the rise of more fuel-efficient cars, as well as increased use of electric cars, has broken the “user fee” model for the traditional gas tax. Ideally, drivers would pay more as they drive more to account for their share of wear and tear on roads. But electric cars pay no fuel taxes at all and fuel-efficient vehicles pay less than their relative share.

Unfortunately, a VMT currently requires an unacceptable tradeoff between forcing drivers to overpay or invading their privacy with GPS tracking devices. For example, in Oregon drivers must choose between allowing a tracking device to be installed in their vehicle or a GPS-free dongle that tracks miles. The first choice requires giving up privacy and the second means drivers could overpay if they drive out of state or in private lots. While technology might solve this trade-off, no solution currently exists.

There are multiple proposals currently before the General Assembly to raise revenue through more traditional taxes and fees, two of which seek to raise nearly $2 billion annually according to reporting by the Daily Herald. These plans are:

- House Bill 3823, which has support from the Illinois Chamber of Commerce, would more than double Illinois’ motor fuel tax to 44 cents a gallon from 19 cents during the course of five years. The initial increase would take place July 2019, raising the state’s current 19-cent tax to 34 cents per gallon. The tax would rise by 2 cents per gallon annually until reaching 44 cents in 2024. In return, the bill phases out the state general sales tax on gasoline.

- Senate Bill 103, which is supported by Local 150, would increase the state motor fuel tax to 38 cents and index it to inflation thereafter, with a 1-cent annual cap. The bill would essentially make gas tax increases automatic, reducing political pressure on lawmakers to spend existing dollars more efficiently and avoid relying on additional revenues as the only method for funding infrastructure spending.

Both bills would increase numerous fees for vehicle and license registration.

One recent gas tax hike proposal is House Bill 391 from state Rep. Michael Zalewski, D-Chicago. It was not accompanied by a revenue estimate. Like the other two proposals, it would hike fees on license and registration renewals. The bill would increase the gas tax to 44 cents per gallon, but all at once on July 1, 2019, rather than over five years like the chamber-backed proposal. It comes with the same automatic annual increases as Local 150’s proposal, with a 1 cent per year cap, allowing the gas tax to increase every year without holding lawmakers accountable for the vote.

The only positive aspect of the Zalewski bill is it would require a data-driven project selection process.

There is some evidence lawmakers understand the likely taxpayer backlash. State Sen. Martin Sandoval, D-Chicago, introduced an amendment to House Bill 3323 that mirrors the Zalewski bill – including a 44-cent state gas tax and prioritizing projects. Sandoval got the Senate to suspend the rules so he could get his bill out of committee on May 14, but then he ended the committee meeting within minutes so he said he could continue negotiating to scale back some fees, such as the $1,000 electric vehicle fee. The gas tax increase may also be in play.

Proponents say the Illinois gas tax has not increased since 1990, when it was set at 19 cents per gallon, while most states raised their gas taxes in recent years. This implies the base motor fuel tax is too low. Advocates for higher gas taxes and inflation indexing also claim the purchasing power of the motor fuel tax has decreased over time because the motor fuel tax has not risen with the price at the pump.

These claims are misleading.

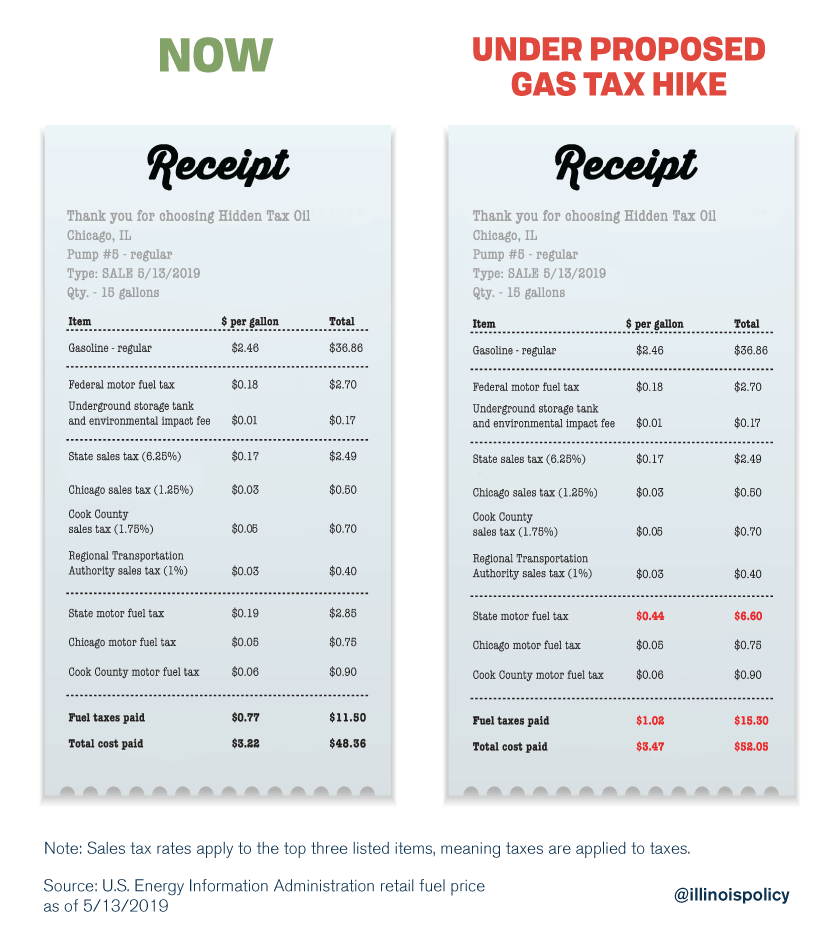

First, Illinoisans currently pay the 10th highest average total state and local tax burden on gasoline at 37.32 cents per gallon, according to the Tax Foundation. The Tax Foundation uses a methodology developed by the American Petroleum Institute which measures total effective gas tax rates, not just motor fuel taxes, to see how much consumers actually pay at the pump. The Prairie State is one of just seven states where drivers pay general state and local sales taxes on gasoline purchases. Drivers also pay underground storage and environmental fees of 1.1 cents per gallon, along with various local charges.

To see how these costs add up, consider the typical Chicagoan’s gasoline bill that includes the following taxes per gallon, then compare that to what would happen should Zalewski’s HB 391 pass:

An 18-cent increase in the motor fuel tax, as Local 150 wants, would move Illinois up to second in the Tax Foundation’s ranking of total average gas taxes, just behind Pennsylvania’s 58.7 cents per gallon. A 25-cent increase as proposed by Zalewski and Sandoval would give Illinois the highest gas-tax rate in the nation.

Second, because Illinois sales tax on gasoline is percentage based, revenue from gasoline sales does vary with the price of gasoline over time. For this reason, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy includes Illinois on its list of 22 states with variable-rate gas taxes.

The problem is that sales tax collections from gasoline purchases currently go into the state’s general revenue fund, rather than being dedicated to transportation.

Illinois residents don’t want tax- and fee-hikes on drivers – they’re right to be wary

Who opposes an increase in taxes and fees on drivers? The vast majority of Illinois residents.

A poll commissioned by AAA from January to February 2019 found that 74% of Illinois residents would be unwilling to pay more in taxes and fees, and an equal 74% don’t believe Illinois uses current infrastructure dollars appropriately.

Another notable finding of that poll is that while only 27% of Illinoisans believe the state’s infrastructure is good or excellent, 47% believe it is “fair” and just 26% consider it to be poor or terrible. Michigan residents rank their infrastructure significantly worse – 60% poor or terrible, just 13% good or excellent – despite the state’s higher effective gas tax rate of 44.13 cents per gallon.

A key lesson for lawmakers is that more infrastructure spending does not always mean better infrastructure quality. How you spend money is often more important than how much you spend.

“An almost inverse relationship exists between the resources that state governments take in and how effectively they build and maintain infrastructure,” Steven Malanga, a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, recently argued in the City Journal. Comparisons of data from the Tax Foundation’s gas tax rankings and infrastructure quality rankings show the argument has merit.

There is no statistically significant relationship between a state’s total gas tax per gallon and its rankings on the U.S. News and World Report’s Infrastructure Rankings or 24/7 Wall Street’s States that Are Falling Apart report. In fact, while the correlation is not strong enough to be statistically significant, there is actually a negative relationship between high gas taxes and infrastructure upkeep.5 That means states with higher gas taxes are actually “falling apart” slightly more, on average.

Pennsylvania, the state with the highest total gas tax, ranks 29th in terms of infrastructure quality, according to U.S News. It has the fourth worst state of disrepair, according to 24/7 Wall Street.

Illinoisans are all too familiar with seeing their infrastructure dollars wasted and misspent.

In 2017, a federal investigation into hundreds of “staff assistant” hires made at the Illinois Department of Transportation found the agency had for years been doling out patronage jobs to politically connected applicants. The agency pushed candidates through the application process with “‘little or no regard’ for actual hiring need, or whether the candidate was qualified for the job,” according to the Chicago Tribune.

And in September 2018, the Daily Herald reported the board chair of the Illinois State Toll Highway Authority awarded a number of six-figure positions to political allies. The agency had also contracted with firms staffed by officials’ relatives and former political associates to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars.

Finally, Illinoisans are used to seeing hundreds of millions of dollars in infrastructure revenues diverted annually to prop up politicians’ overspending. From fiscal year 2002 to fiscal year 2015, Illinois politicians swept $6.8 billion from transportation funds to pay for other expenses. This led to voters approving a “Lockbox Amendment” in 2016 with nearly 79% of the vote.

The lockbox means taxes and fees collected from transportation sources can only be used for transportation-related spending, such as a capital bill.

This reform may give Prairie State residents some confidence their gas tax dollars will not be squandered. Still, the case for tax- and fee-hikes on drivers will remain weak until reforms are enacted to maximize each dollar spent and until patronage scandals become a thing of the past.

A no-tax-hike capital plan

It is easy to focus on Illinois infrastructure at its worst, such as when a Chicago Transit Authority retaining wall broke loose and fell on April 18, crushing two parked cars. The political reaction to these stories implies there’s no infrastructure spending and everything is crumbling.

In reality, Illinois ranked 34th – in the bottom half of states for needed repairs in 2018, according to 24/7 Wall Street. The state already has significant capacity to fix roads and bridges with existing revenues.

Pritzker’s proposed 2020 Capital Budget requested a total of $17.6 billion in capital spending authority from the General Assembly, including bond-financed projects and pay-as-you-go infrastructure spending. New spending authority in the budget request totals $3.7 billion, including $600 million in spending for deferred maintenance at state agencies, $150 million for repairs and upgrades to higher education facilities, and $1.8 billion for the Illinois Department of Transportation to work on roads and bridges. This spending is entirely separate from the state’s general operating budget, and is based on existing revenues.

More maintenance spending on infrastructure could benefit the state. However, lawmakers should be patient and restrained in the scope of a new capital bill, adopt project selection reforms and lessen labor mandates to maximize return on investment. They should dedicate existing or proposed revenue sources to new spending rather than hike taxes and fees on drivers.

The easiest option is to stop diverting the state’s gasoline sales tax revenue into the state’s general funds. Use it for infrastructure spending as intended. By legally mandating this source of money be used only for capital spending, lawmakers would be acting in the spirit of the Lockbox Amendment approved by voters. This change would also address the concerns of some advocates that motor fuel tax revenues do not rise with the price of gasoline, because the sales tax is percentage-based and variable.

Changing where sales tax revenue from gasoline sales is deposited would cost the general funds budget about $514 million per year, but this could be offset with savings reforms. For example, asking state workers to pay for 40 percent of the cost of their generous health insurance packages, up from just 23 percent, would save roughly the same amount annually. This reform would also bring government worker health insurance costs more in line with private sector employee shares. Notably, Illinois state workers are already the second-highest paid in the nation when adjusting for cost of living.

Next, lawmakers should look to dedicate revenue from legalization of sports betting to transportation purposes. Many states are moving to legalize sports betting after a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision enabled the change. Pritzker advocated for legal sports betting during the campaign and in his budget address called for a 20% tax rate estimated to raise as much as $136 million annually. Expanding gambling was also the most popular option among Illinois residents for raising additional revenue for infrastructure in AAA’s poll, at 39% approval.

If both of these revenue sources were secured for infrastructure bonds, Illinois could front-load its infrastructure spending with a $5.8 billion infusion. Secured bonds also generally require lower interest costs, a necessary goal given Illinois’ worst-in-the-nation credit rating.

If local sales tax revenues from gasoline totaling nearly $430 million were also dedicated to transportation purposes by state law, total additional guaranteed state and local spending during 10 years could exceed $10 billion. This would ensure local governments spend their gasoline sales tax revenues on transportation, in the spirit of the Lockbox Amendment. As in Virginia, projects with significant local resources would score higher on the Smart Scale because they require less in state resources.

This $10-billion infusion, on top of the state’s existing $17.6-billion spending capacity, would enable Illinois to address the state’s most critical infrastructure needs now. Additional capital spending could then be put on hold until economic conditions change and details of a federal infrastructure plan are finalized to maximize matching grants.

Coupled with the transparency and efficiency reforms of data-driven project selection and wage mandate relief, a no-tax-hike capital plan will protect Illinois drivers and provide them with confidence that they are getting value for their taxes.

Endnotes

- See for example: Felix K. Rioja, 2003, “The Penalties of Inefficient Infrastructure,” Review of Development Economics, 7(1): 127-137; Felix K. Rioja, 2003b, “Filling Potholes: Macroeconomic Effects of Maintenance Versus New Investments in Public Infrastructure,” Journal of Public Economics, 87(9-10): 2281-2304; Pantelis Kalaitzidakis and Sarantis Kalyvitis, 2004, “On the Macroeconomic Implications of Maintenance in Public Capital,” Journal of Public Economics, 88(3-4): 695-712; Pierre-Richard Agenor, 2009, “Infrastructure Investment and Maintenance Expenditure: Optimal Allocation Rules in A Growing Economy,” Journal of Public Economic Theory, 11(2): 233-250.

- See for example: Giancarlo Corseeit, Andre Meier, and Gernot J. Muller, 2012, “What determines government spending multipliers?”, Economic Policy, 27(2); 1. Lawrence Christiano, Martin Eichenbaum, and Sergio Rebelo, 2011, “When is the Governemnt Spending Multiplier Large?,”Journal of Political Economy, 119 (1).

- Ethan Ilzetzki, Enqirue G. Mendoza, and Carlos A. Vegh, 2013, “How Big (small?) Are Fiscal Multipliers?”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 60(2): 239-254.

- Author previously worked for the Illinois Department of Labor on a process to move away from reliance on collective bargaining agreements and determine a true market wage through industry surveys, which was stopped pursuant to litigation and legislative action.

- Tax Foundation’s total gas tax ranking is positively correlated with infrastructure rankings by U.S. News and World Report with a correlation coefficient of just .154, short of statistical significance. Total gas taxes are correlated with a higher ranking on ‘Sates Falling Apart’ at .246, with higher rankings indicating a higher state of infrastructure disrepair.