Heavy metals: Behind the fall of Illinois industry

By Austin Berg

Future

Jesse Huerta may be the shortest man in the building, but he walks tall across the factory floor at Tri-State Industries Inc. in Hammond, Indiana. Tri-State manufactures robotics, among other fabricated metal products. Huerta is the assistant plant manager.

“Every day I see people from Chicago moving out here,” he said. “It’s not because we’re a poor city, it’s not because the government doesn’t have our back, it’s because they know there’s work out here. They know you can still have a future out here.”

“And really that’s what everybody’s looking for, is a future.”

Huerta knows this better than most. He was born and raised in Chicago, but his two daughters will grow up as Hoosiers. His life at Tri-State is a far cry from what he left behind on the other side of the state border.

Before Huerta moved to Indiana, his South Side Chicago employer went belly-up. Chains bound the double doors Huerta walked through for three years to his factory job. He joined the ranks of the unemployed.

“The union stewards never told us a thing,” he said. “You pay your dues all those years … I was infuriated.”

He moved to Indiana for seasonal work in construction but left that job to find stable income on which to raise his family. The morning Huerta walked out on construction, he walked into Tri-State, which offered him an entry-level job making shipping blocks.

Huerta quickly moved his way up the ranks.

“For me personally [this job] is life-changing,” Huerta said. “The skills that I’ve learned here I didn’t come with.”

Middle-class manufacturing opportunities like Huerta’s are growing fast in Indiana. In fact, contrary to the narrative of Midwestern industry being crushed by cheap labor in China and Mexico, federal jobs data indicate Great Lakes states such as Wisconsin, Michigan, Indiana and Ohio are experiencing a manufacturing renaissance.

But that’s not what’s happening in Illinois, the state Huerta left behind for a better future.

Fallout

From Elgin to Effingham, Peoria to Pontiac, Galena to Granite City, Illinois was once a manufacturing titan.

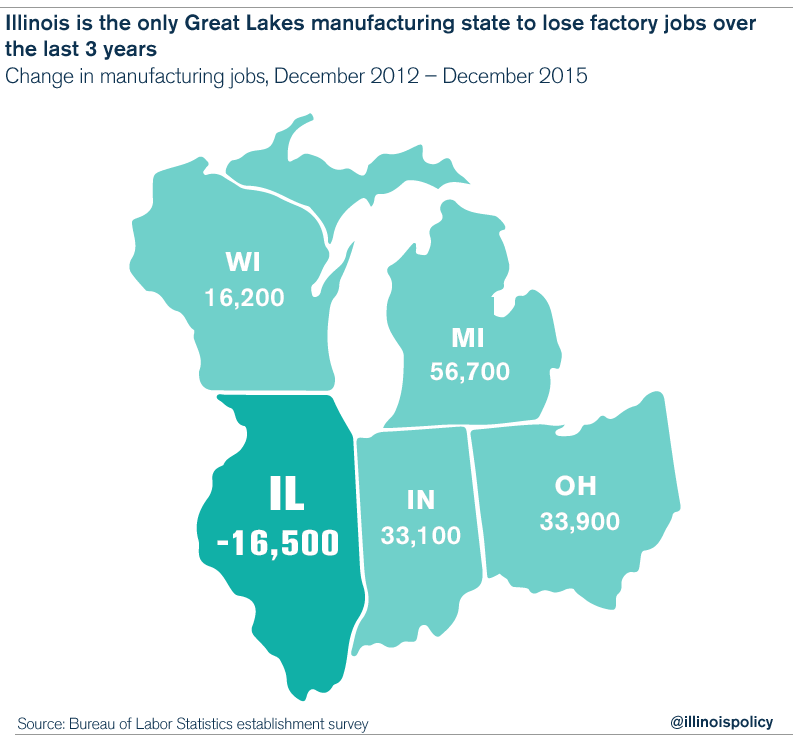

But now, when it comes to forging middle-class jobs through a strong manufacturing sector, it is a laggard state. Illinois is the only Great Lakes manufacturing state to lose factory jobs over the last three years.

Illinois is also home to a devastatingly weak manufacturing recovery in the wake of the Great Recession. Since Illinois’ recession bottom, manufacturing jobs have grown by a mere 2.7 percent, the lowest rate by far among surrounding states.

The Illinois manufacturers that can afford to keep workers on the job are cutting costs on salaries. Production workers in Illinois take home the lowest pay in the Midwest.

Meanwhile, Michigan passed Illinois in late 2014 for total manufacturing jobs with a workforce less than three-quarters the size of Illinois’. And Indiana is on its way to passing Illinois for manufacturing jobs with a workforce half the size. According to the BBC, the Hoosier State is “the nation’s leader in manufacturing.”

The Rust Belt is rising again. But Illinois is floundering. Neighbors are flush with well-paying manufacturing jobs, while the Land of Lincoln shrugs.

The family-owned businesses that create those jobs know why this is the case, but as of yet, their cries for help have not been met with action in Springfield.

Failure

Steel from the Selvaggios built the governor’s mansion. Now, Mark Selvaggio says his family-owned fabricating business in Springfield, Illinois, is lucky Indiana industry is seeing success. Across the state border, firms just like his send extra work Selvaggio’s way.

“There’s nothing being built here anymore,” Selvaggio said. “Illinois work is completely flat or down compared to all of the surrounding states, and it’s crushing us.”

“Everybody asks if I want an incentive to hire someone to come in. I don’t need their $5,000. I need work.”

One major expense Selvaggio says is killing work in his industry? Workers’ compensation costs. Compared to Indiana, Illinois manufacturers often pay triple the cost for insurance to pay injured workers.

Some may think these expensive insurance premiums mean Illinois workers are safer. Far from it, according to Jesse Huerta.

“No. That’s not how it works,” he said. In addition to serving as the assistant plant manger, Huerta is head of safety for Tri-State.

“When I worked in Illinois I never went through one safety class. I never saw one safety video. When I was driving a forklift, it was, ‘You know to operate it? Know what these levers are for? Go for it.’”

In fact, high labor costs can lead to disastrous outcomes for workers, according to Huerta.

“In Illinois, those jobs … it’s value,” he said. “[Employers] are paying so much money to have [workers] in the building that [they] need workers to push and get as much stuff out to justify the cost of being open. Therefore, [they’re] going to turn a blind eye.”

“Here, I don’t care how fast you’re going. I don’t care how much more money you’re making. If you’re doing it unsafely, we’re going to stop you right there.”

Not only can these high costs impact worker safety in Illinois, they also prevent employers such as Selvaggio from growing their businesses, and can even push well-paying jobs out of the state altogether. Professor Don Haider at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management spoke to this “irritant” for Illinois employers.

He noted that too often, Illinois’ workers’ compensation system does not function to the benefit of worker interests, but rather to that of legal insiders.

“We have a number of states in this area that Illinois can easily benchmark against … [in terms of] protections to workers and to their employers that are paying this cost,” Haider said.

But workers’ compensation is far from the only “irritant” Illinois manufacturers endure, as business leaders may tell you on their way out of the state.

Flight

When Marty Flaska moved his forklift business to Illinois 17 years ago, he never compared the cost of doing business across state lines. Last year, his son showed him the numbers.

“I didn’t believe him,” Flaska said.

By the end of 2015, Flaska will have moved nearly 300 manufacturing jobs at Hoist Liftruck Manufacturing Inc. out of Illinois. Those jobs will be at a brand-new Hoist facility in East Chicago, Indiana, along with 200 more that Flaska plans to create. The average pay for one of those positions is $55,000.

His reason for moving was simple. “It’s all about cost,” Flaska said.

“When someone starts doing due diligence, it’s a no-brainer. We’ve been working on this for a year, and it’s a given. We’re moving.”

Chief among the costs that forced Flaska out? Uncompetitive workers’ compensation costs and sky-high, volatile property taxes. Illinois is home to the nation’s second-highest property taxes. And Cook County, where Hoist is located, is home to a notoriously corrupt property-tax assessment scheme.

“If I didn’t have the workers’ compensation issue and the extortion of assessors raising property taxes and me having to pay a third of that cost [to attorneys] to get them lowered, I probably never would have even considered moving,” he said.

“Why would I?”

Beyond the dollars and cents of tax rates and insurance premiums, Flaska also cited the difficulty of day-to-day operations in Illinois, waiting up to a year for simple permits he got in a matter of days in Indiana. Uncertainty surrounding where Illinois’ tax rates may go in the future given the state’s enormous financial problems also weighed heavily on Flaska as he considered whether to leave.

Unfortunately, Hoist’s departure for Indiana is just one of a long line of manufacturers that have made a beeline for neighboring states.

For example, Illinois-based manufacturers T&B Tube Co., American Stair Corp. Inc. and Edsal Manufacturing Co. Inc. have all decided to move to or expand in Indiana in 2015.

Losing a manufacturing company is not equivalent to losing a real-estate business, a mall, a bank or a corner store. Not only are manufacturing jobs usually well paying, unlike many retail jobs, but the businesses that provide them are often closely tied to the local economy. Flaska’s “milk run” – his purchases of the materials to make Hoist forklifts – primarily happens within a 200-mile radius of his Bedford Park location.

Illinois businesses are buoyed at every step of the industrial process, and so are the lives of those who work manufacturing jobs, which can often be attained with a high-school diploma and a strong work ethic.

“[This job] changed my whole life, my whole outlook,” Huerta said. “And it changed the lives of the guys here, too. Most of the guys here come from the same walk of life I do: minimal skills, a high-school education, but no money for college.”

“… to know that companies out [in Illinois] are closing left and right, and they’re moving out because financially the state and city are making it so hard for manufacturers to keep their doors open … it’s saddening. I’m saddened because it’s not just one man losing his job, it’s a family losing their way of life.”

Fight

Gov. Bruce Rauner is the first Illinois leader in recent memory to push for a comprehensive set of changes to transform Illinois’ manufacturing climate.

To lower Illinois’ high workers’ compensation costs to levels comparable to those in neighboring states, Rauner has proposed: bringing workers’ compensation medical payments in line with those made by private insurers, tightening the definition of a traveling employee and of an injury caused by employment, and encouraging common sense in arbitrator and judicial rulings on workers’ compensation claims. Rauner has also pushed for a property-tax freeze.

These proposals will help, and still further action will be necessary, for the state’s industrial sector to regain its competitive edge.

But these reforms have not been well received among Springfield’s old guard. Illinois House Speaker Mike Madigan refuses to discuss “nonbudgetary” issues with the governor while negotiating the state budget, even as companies such as Hoist make decisions to leave the state over many of these “nonbudgetary” policies.

Illinois has the potential to be a worldwide leader in combining a tech-savvy urban workforce with skilled labor and brawn. Downtown Chicago could house sales offices for a heavy machinery plant downstate. Autoworkers could build a fleet of self-driving cars in Aurora as programmers work on cutting-edge code in River North. But basic policy missteps must be corrected for manufacturers to start thinking about moving to the Land of Lincoln, or expanding within it.

“I was born and raised in Chicago. And I feel bad for the working man,” said Huerta. “All we need is our head honchos to get their act together and look at the big picture. Who are you representing? Without the people you ain’t got nothing.”