The problem

Opponents of pension reform at the state and local level often argue that the average government-worker pension is modest.

In a May 2011 commentary, government union chiefs Ken Swanson and Henry Bayer wrote that “at the end of a working life devoted to public service, an Illinois teacher, firefighter or librarian retires with an average pension of just $32,000 a year – and many much less.” This low pension figure is recycled repeatedly throughout union messaging materials.

The narrative for city workers mirrors these talking points. The Chicago Teachers Union’s website uses the average pension figure to argue that pensions are modest in the city: “The average Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund (CTPF) retiree earns $42,000 per year.”

But the reality is that government-worker pensions have ballooned to a level that’s no longer sustainable. Today, the average career downstate teacher who retired recently in Illinois earns a $69,600 pension. The average career university worker who retired recently earns a pension of $73,500. Even state workers, a majority of whom earn Social Security, draw an average pension of $45,700.

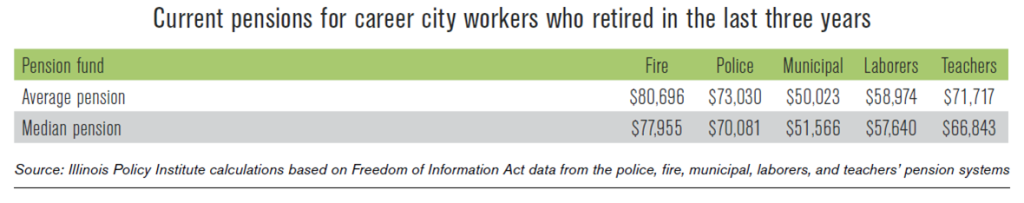

In Chicago, the average pension for career city workers who recently retired totals $65,000.

To be clear, government workers who earn these generous pension benefits have done nothing wrong. They benefit from labor negotiations that have led to lucrative compensation packages. But as the city’s credit rating begins to approach junk-bond status, it’s become obvious that the city’s budget and its taxpayers can no longer afford to offer these benefits.

Pension benefits

Average pension benefits are one of the most commonly used and misleading pension statistics. That’s because averages include older retirees who’ve been retired for a long time and short-term workers who receive relatively small pensions for their limited time working for government.

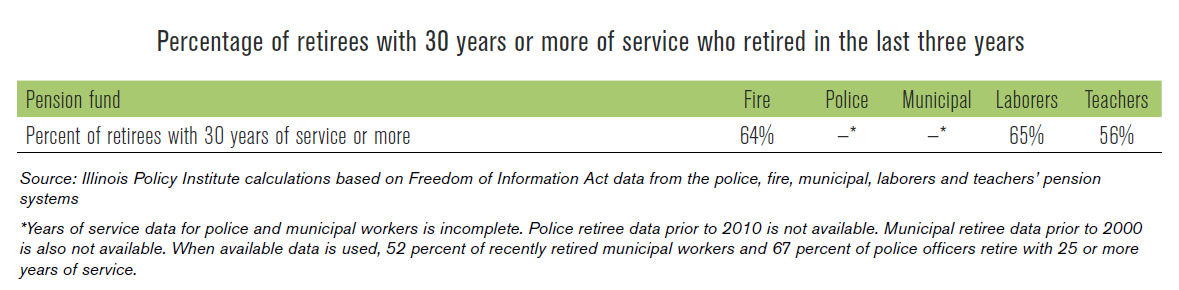

A more appropriate and accurate measure of how generous pension benefits have become is the average pension for a worker who retired recently (within the last three years) and dedicated his or her career (at least 30 years) to city government. Career workers make up about half of all currently retired city workers in Chicago.

The average pension for Chicago teachers is $47,700, which includes short-term workers and individuals who retired years ago at much lower compensation levels.

But the average pension for a career teacher in Chicago who recently retired is $71,700 – a full $24,000 more than the average for all teachers. It’s also more than double the maximum $31,700 Social Security benefit that private sector workers who reach full retirement age can receive.

To put that further into perspective, a recently retired career teacher makes more in retirement than the average Chicago household income ($71,020).

And the median benefit of recently retired career teachers is nearly $67,000. That’s 23 percent higher than the median family income in Chicago ($54,188) and more than double the median earnings of Chicago workers ($31,052).

Demographic realities

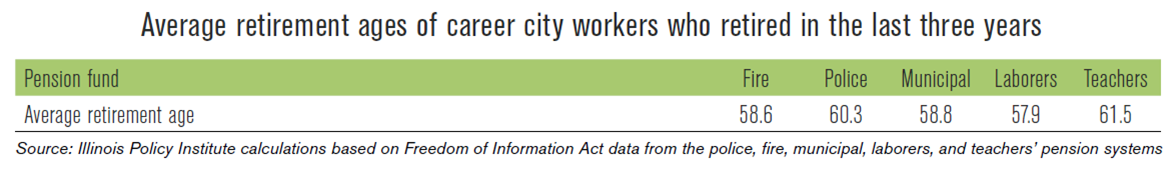

Pension benefits for most career workers don’t reflect today’s fiscal and demographic realities. People are living longer, which means government retirees are collecting more retirement benefits for longer than in the past.

On top of that, the average career worker in Chicago retires at or near the age of 60. some career city workers even retire in their mid-50s while collecting pension benefits equal to most of their final salary. In contrast, private sector workers cannot begin drawing a full Social Security benefit until nearly a decade later – at the age of 67.

Contributions vs. benefits

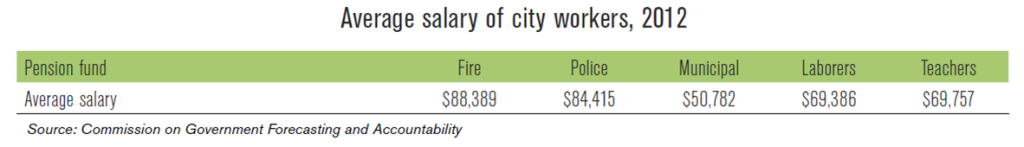

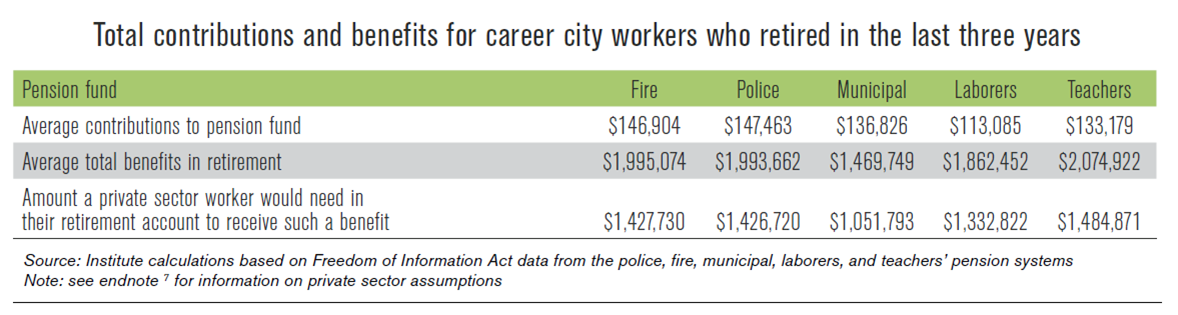

The amount of money a career city worker contributes to his or her pension has no bearing on what that worker will receive in retirement.

With every paycheck, a city employee contributes a fixed percentage of his or her salary to the pension system. Over a worker’s career, their total contributions are based on their average salary. But pension benefits aren’t based on those contributions. Instead, pension benefits are based on a worker’s end-of-career salary, when their salary is likely to be at its highest point.

Retirees with 30 or more years of service will receive, on average, total pension benefits nearing, and sometimes exceeding, $2 million over the course of their full retirement. In contrast, an individual in the private sector would need to have $1 million to $1.5 million in the bank at the point of retirement to purchase an annuity that mirrors what career city workers receive during retirement.

Case study: Chicago Public Schools

Rhea Fries Boldman’s experience as a Chicago Public Schools teacher reveals just how out of sync city worker contributions are compared to the benefits they receive.

Boldman retired in 2012 at the age of 59 with a final average salary of $87,057.

Boldman is receiving an annual pension of $71,674 – and she will receive $2.4 million in pension benefits during her retirement if she lives to her full life expectancy.

Yet she contributed just $147,032 to the pension system over her 30-plus year career. Her direct contributions to the Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund will cover just 6.2 percent of her expected lifetime benefits. Including the interest earned on those contributions, the total would cover approximately 12 percent of her expected lifetime pension benefits.

Chicago Public Schools – and by extension city taxpayers – will foot the lion’s share of Boldman’s pension benefits in retirement.

That’s the problem with the current system: worker contributions are completely unrelated to their retirement benefits.

Current pension benefits for city workers are no longer sustainable or affordable.

It’s not fair to ask Chicago workers, who earn a median income of $31,052, to pay for career government workers to retire in their 50s and draw lifetime pension benefits nearing $2 million. The overgenerous pension benefits are also unfair to the poor and disadvantaged who suffer as the city cuts core government services to pay its rising pension costs.

The solution

The Illinois Policy Institute has developed a comprehensive reform plan that aligns the structure of public-sector retirement with the private sector, while protecting what current workers have already earned.

The core of the Institute’s solution is a retirement plan that gives city workers a self-managed 401(k)-style retirement plan and a Social Security-like benefit. This allows their savings to grow with the market while providing a stable source of income each month.

The plan also makes retirement costs a stable and predictable portion of Chicago’s budget and helps prevent indiscriminate cuts to core government services due to rising pension costs. Finally, the Institute’s plan protects taxpayers from paying higher taxes to fund ever-growing pension shortfalls.

The Institute’s holistic pension reform plan is the only plan on the table that puts Chicago back on a path to financial security and aligns the structure of public-sector retirement with the private sector.