Chicago’s ban on food carts is costing the city jobs and revenue. The city has fallen behind its peers: Street vending from food carts is already legal in 23 of the 25 largest cities in the U.S.

The Illinois Policy Institute conducted a survey of nearly 200 Chicago food-cart street vendors to assess the social and economic impact of their activity on Chicago’s neighborhoods, and to project the potential economic gains that could be realized by legalizing and legitimizing this form of commerce. Institute research found that this form of commerce currently generates an estimated $35.2 million in annual sales, $16.7 million in annual income, 2,100 jobs and as many as 50,000 meals served per day. Legalizing this occupation holds the potential of dramatic growth in the industry.

Who are Chicago’s food-cart street vendors?

Here are quick facts on the industry’s demographics based on Institute survey results:

- Most vendors are middle-aged: 78 percent are age 35-64

- 55 percent are women and 45 percent are men

- 100 percent of vendors surveyed are Hispanic, with the vast majority of vendors reporting Mexican heritage

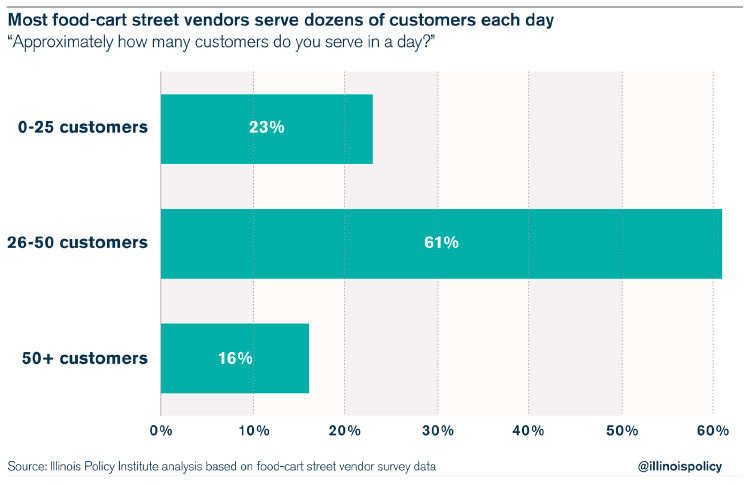

- Most vendors serve between 25-50 customers per day

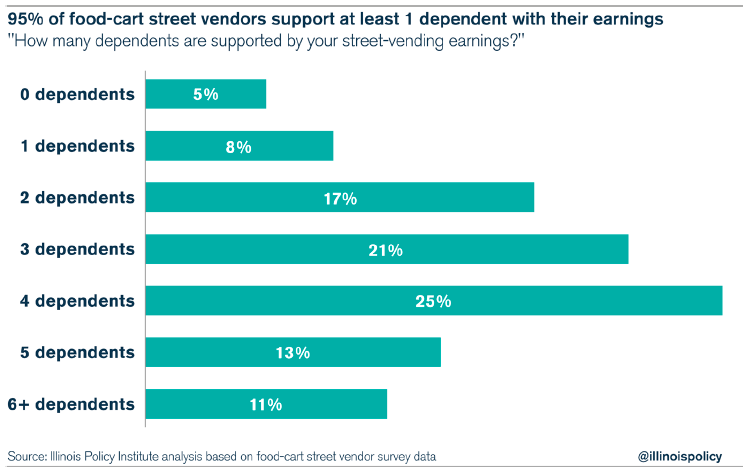

- 95 percent of vendors support at least one dependent with their earnings

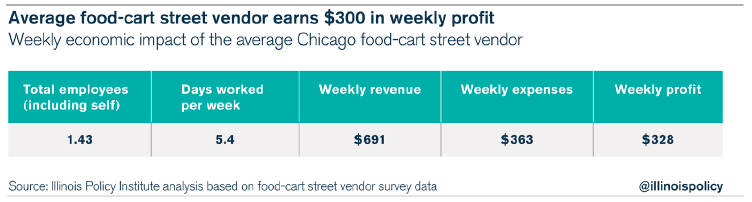

- The average vendor generates $691 per week in revenue and spends $363 per week on expenses, earning $328 per week in profits

- The average vendor employs 1.43 people, including himself or herself, and works 5.4 days per week

Why do vendors pursue this profession?

- Most vendors said they could not find other work due to age, health or poor job prospects in the city

- Many vendors enjoy the flexible schedule this career path offers

- Some vendors enjoy the profession’s roots in Hispanic culture, and view the work as a family tradition

What makes life for food-cart street vendors difficult, aside from the city banning their trade?

Street vendors face a variety of risks and challenges, largely based around the legality of their occupation. All of this could change for the better if Chicago legalized food carts. The city has immense, untapped potential for millions of dollars worth of growth in the street-vending industry, according to Institute research.

Here’s what Chicago could see if it legalized food carts:

- 2,145 jobs legalized, with the potential for as many as 6,435 jobs on top of that

- $40 million to $160 million in total annual sales

- $19 million to $78 million in annual earnings

- $2 million to $8.1 million in new state sales-tax revenues, and $2.1 million to $8.5 million in new local sales-tax revenue

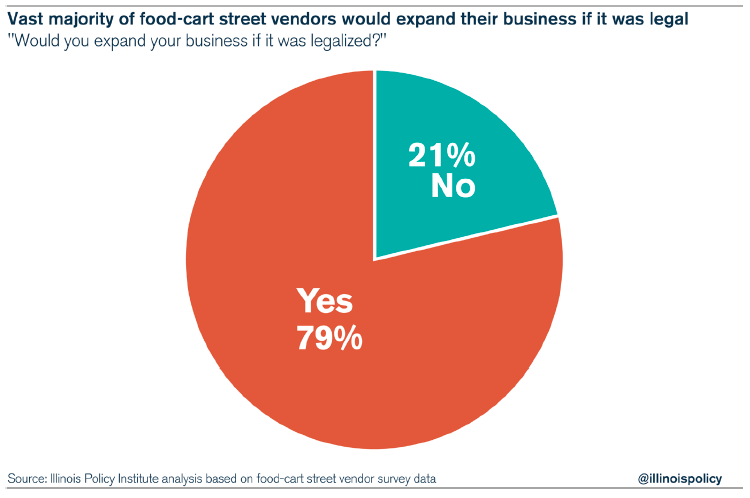

- 79 percent of current vendors would expand their business

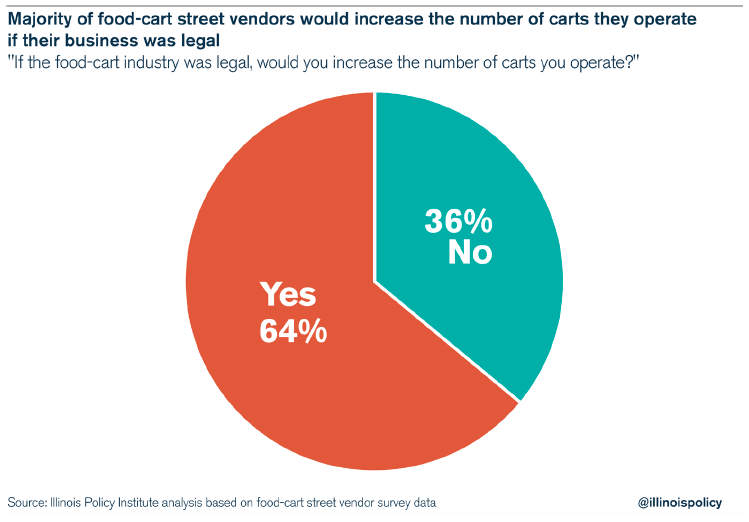

- 64 percent of current vendors would add more carts

- Thousands of new entrepreneurs would be able to enter this occupation

Chicago’s regulations are hurting residents, whether they are entrepreneurs trying to make a living as street vendors or hungry workers looking for a good meal near their home or place of employment. The ban on food carts isn’t stopping all of these vendors, it is simply driving them underground and thwarting opportunities for growth and expansion. Keeping food carts illegal reduces food safety and dramatically hurts the well-being of vendors, especially in immigrant communities. The total loss due to current laws, in terms of economic growth and human potential, is devastating. It’s time for Chicago to legalize food carts.

Introduction

Chicago should seize the opportunity to cultivate a new flavor of entrepreneurs

Chicago’s immigrant entrepreneurs have fought for more than a decade to legalize food carts, an affordable small business that enables many to provide for themselves and their families. The city of Chicago should legalize food carts so entrepreneurs can flourish and serve customers across the city.

Out of the 25 largest American cities, Chicago is one of only two that do not allow street vending from food carts (see Appendix 1). This regulation is harmful to Chicago’s immigrant population, and it also stunts the positive economic impact that these entrepreneurs can have on Chicago’s economy.

There are estimated to be 1,500 food-cart street vendors operating across Chicago,1 creating and distributing fresh meals to workers across the city, oftentimes in neighborhoods where there aren’t plentiful food options. This entrepreneurship is having a significant and positive economic impact in terms of generating millions of dollars in sales for wholesale food suppliers, thousands of jobs for vendors and most importantly, an honest day’s work that will allow immigrant entrepreneurs to support their families and cultivate the spirit of entrepreneurship in Chicago.

The Illinois Policy Institute conducted a survey of nearly 200 Chicago food-cart street vendors to assess the social and economic impact of their activity on Chicago’s neighborhoods, and to project the potential economic gains that could be realized by legalizing and legitimizing this form of commerce.

The Institute’s findings show this form of commerce generates an estimated $35.2 million in annual sales, $16.7 million in annual income, 2,100 jobs, as many as 50,000 meals served per day and the untapped potential for millions in new sales-tax revenues. The best part about this is that street vending provides an economic stimulus for lower-income neighborhoods, which are the primary areas of operation for vendors. And these estimates are almost certain to go up dramatically if food-cart street vending is legalized. That’s because new entrepreneurs will be attracted to the industry and current vendors will be able to expand their operations. The potential total economic impact upon legalization ranges as high as $162 million in annual sales, $77 million in annual income, 8,580 total jobs and 230,000 meals served per day, creating a compelling case for legalizing and licensing Chicago’s next generation of culinary entrepreneurs.

A city can be judged by how it treats its most vulnerable populations, especially those who are striving hardest to create something positive for their neighborhoods. The city of Chicago should do the right thing and open the gates of the American dream for the next generation of American entrepreneurs.

Methodology

There are two primary data sources used in this study: the U.S. Census Bureau and a survey of food-cart street vendors conducted by the Illinois Policy Institute from April 2015 through June 2015. The data from the U.S. Census Bureau are publicly available, and the use and citation of that data is straightforward.

The Illinois Policy Institute’s survey of food-cart street vendors was conducted through in-person interviews, conducted in Spanish, most frequently at a vendor’s location of commerce or at wholesale grocers where vendors purchase food supplies. Some interviews were also conducted at meetings of the Asociación Vendedores Ambulantes, or AVA, an advocacy group whose membership is made up of Hispanic street vendors. See Appendix 2 for the survey questionnaire.

The Illinois Policy Institute worked with the Institute for Justice Clinic on Entrepreneurship at the University of Chicago Law School, which has been a leading organization both in supporting street vendors with legal services and in drafting the ordinance proposal for legalizing food carts. The Institute also collaborated with AVA, which opened up its meetings to our researchers and provided keen insight into street vending in the Little Village and Pilsen neighborhoods.

Completing one survey took an average of 15 minutes, depending on how busy the vendor was with serving customers. Survey responses were averaged to determine the economic impact of a single vendor, and then applied to the entire population of 1,500 food-cart street vendors in Chicago to project the total economic impact of street vending in the city. Modeling the potential economic impact of legalizing street vending was done by benchmarking potential growth in Chicago against other cities that have more liberal vending policies.

Street vending is seasonal, and food-cart street vendors vary widely in what months they are active. As such, a conservative estimate of 34 active weeks per year was applied across the vendor population when calculating annual economic impact.

Out of the entire estimated population of 1,500 food-cart street vendors, our surveyors were able to find and survey 13.3 percent of them.

Demographics

Who are Chicago’s food-cart street vendors?

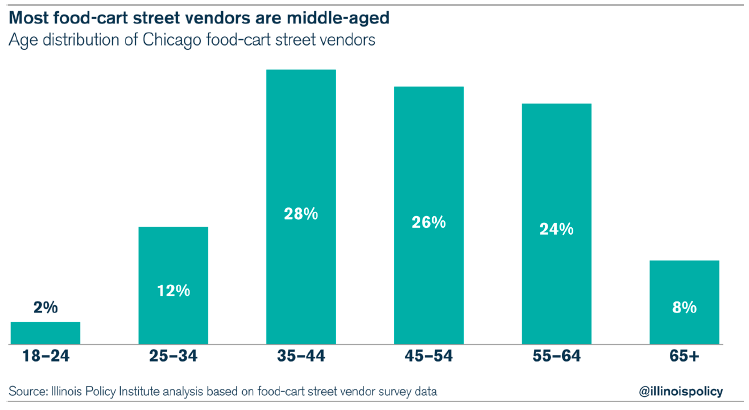

Chicago’s food-cart street vendors range in age from their early 20s to over 65 years old, and more than half of all vendors are women. Most street vendors are middle-aged, with 78 percent of street vendors being between 35-64 years old.

It is interesting to note that 8 percent of vendors are over 65 years old, and age likely plays a role in why they are street vendors. According to a question on the survey about why vendors chose this profession, several respondents reported they are too old to get other work, indicating that food-cart street vending is a way for older folks to make ends meet when they are not eligible for other work.

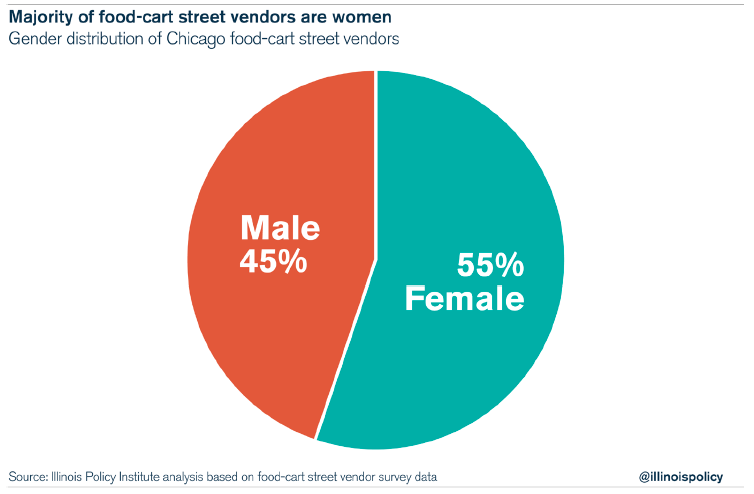

Fifty-five percent of food-cart street vendors are women and 45 percent of vendors are men.

Employees and customers

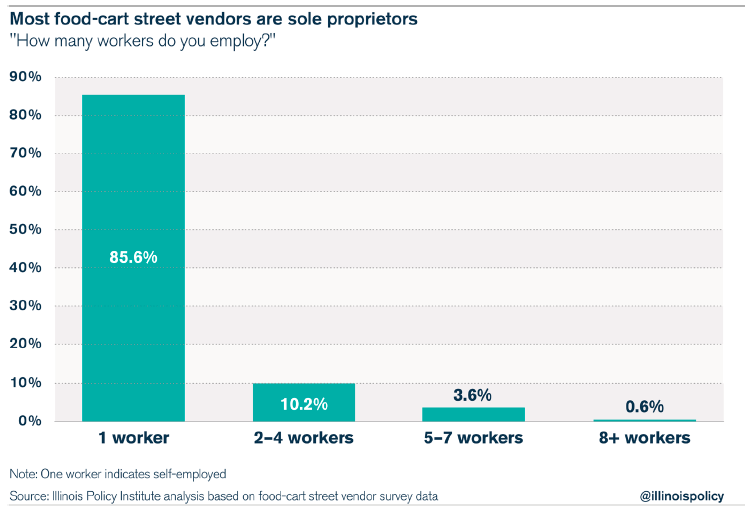

The overwhelming majority of food-cart street vendors are sole proprietors. Less than 15 percent of all vendors have regular employees, although many indicated they would grow their business and hire if food carts became legal. The average street vendor has 1.43 employees, including him or herself.

All of the vendors surveyed were Hispanic, with the vast majority reporting a Mexican national heritage. Other nationalities represented in the surveyed population include Peruvian, Guatemalan and El Salvadorian. All street vendors surveyed reported Spanish as a first or primary language.

Food-cart street vendors sell a variety of products. The most common products are tamales, elotes (corn), chicarrones (pork meat and rinds), cut fruit, shaved ice, fruit drinks and hot cocoa.

Seventy-seven percent of survey respondents indicated they serve more than 25 customers per day, with 16 percent of all vendors serving more than 50 customers per day.

With as many as 1,500 food-cart street vendors operating per day and each serving an average of 36 meals per day, Chicago street vendors serve as many as 50,000 meals per day.

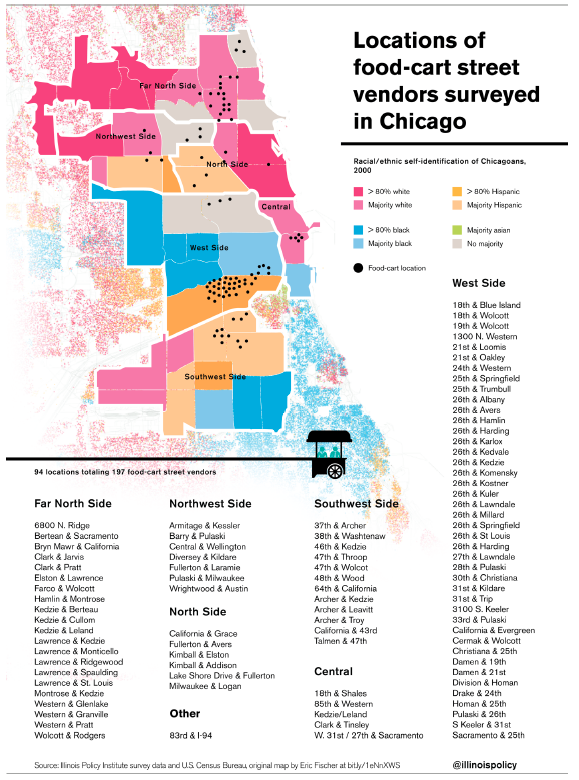

Locations throughout the city

The most popular neighborhood for street vendors is the primarily Hispanic Little Village neighborhood. Pilsen, another Hispanic neighborhood, is also a popular location for street vendors. Most commonly, street vendors operate in minority neighborhoods, serving minority and immigrant customers.

Motivations for street vending, supporting family and dependents

Survey respondents were encouraged to provide a unique answer to describe why they choose to engage in street vending as a profession. The motivations for food-cart street vending vary widely. However, there were several recurring themes:

- No other options

- The most common response was some form of the fact that the vendor could not find other work

- Several vendors cited their age and health as reasons why it was difficult to find work elsewhere

- Other vendors said they consistently tried for other work but were never called back

- Flexible schedule

- Some vendors cited the freedom of schedule as a primary reason for preferring this occupation

- Vendors with families cited the flexible schedule of street vending as ideal for raising children

- Better than alternatives

- Vendors cited the grueling nature of some factory jobs and the risk of workplace injuries to explain why they prefer street vending over factory work

- Street vending provides many workers with a more consistent income than temporary work

- Street-vending wages are better than alternative wages for many of the higher-earning vendors

- Heritage, culture and enjoyment of the occupation

- A few vendors cited their heritage and family tradition for choosing to be street vendors

- Others simply said they enjoy their vending occupation

The four themes point out respondents’ decision to make a living by street vending over alternative occupations. However, the overriding factor that drives workers into street vending is the need to take care of family and dependents. Ninety-five percent of respondents said they used earnings from street vending to support at least one dependent. Eight percent support one dependent with earnings, 17 percent support two dependents, 21 percent support three dependents, 25 percent support four dependents, 13 percent support five dependents and 11 percent of workers said they used their earnings to support six or more dependents.

Thus, the average vendor uses earnings from work to support 3.4 dependents. The entire population of 1,500 food-cart street vendors supports over 5,000 dependents with earnings from their occupation.

Primary concerns of food-cart street vendors

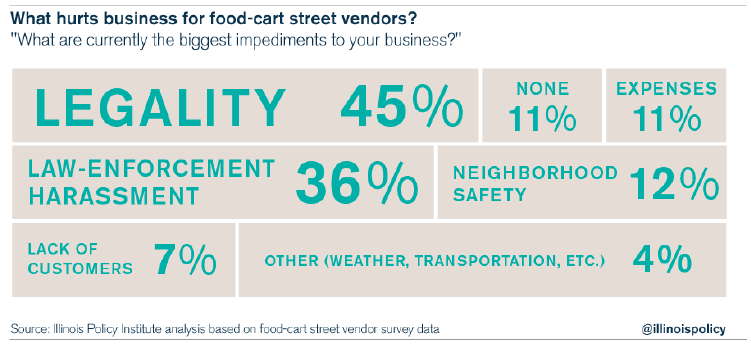

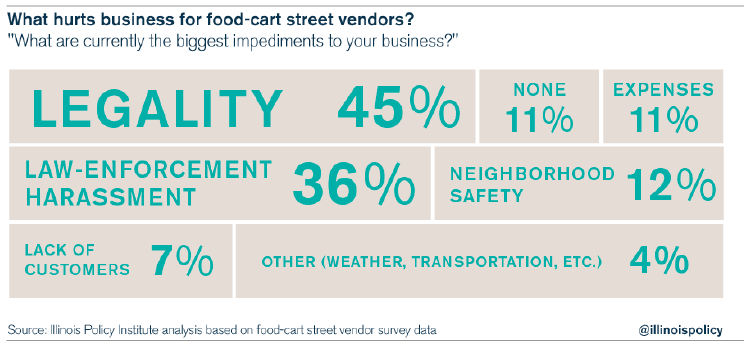

The primary business concerns of street vendors are the legality of their occupation and potential harassment from law-enforcement officials. Neighborhood safety came in a distant third place as a concern.

Street vendors often operate in neighborhoods that present the possibility of robbery and other forms of serious crime. In Chicago, there is no shortage of real crime and violence for law enforcement to deal with. That makes it especially strange for law-enforcement resources to be used to shut down a legitimate form of commerce that supports thousands of dependents.

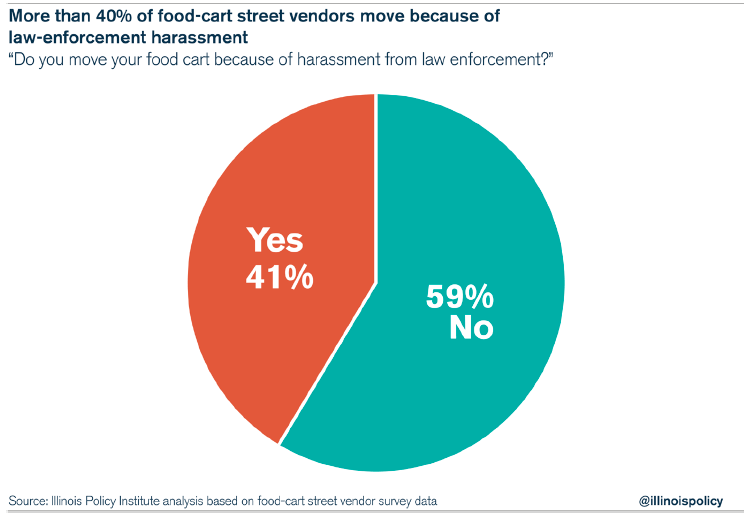

More than 40 percent of respondents indicated they had to move their location because of harassment by law enforcement. This harassment leaves these vendors in less prime locations, costing them in lost business due to less-than-ideal locations and time wasted for relocating their operations, in addition to the costs of police tickets and court appearances.

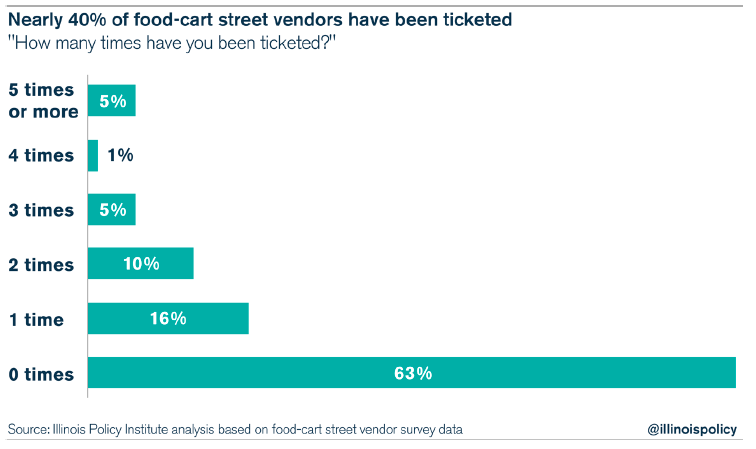

Thirty-seven percent of respondents admitted to having been ticketed by the police for operating their food carts, and more than 20 percent of respondents had been ticketed multiple times. It’s possible that these estimates are on the lower end, as vendors might have been reluctant to disclose a possible criminal record as part of the survey.

The prospect of food carts becoming legalized

Because food-cart street vendors operate in the shadow of the law, they are not able to achieve as much growth and sales as they would if their occupation was legal. The top two concerns of vendors are the legal status of their operations and the possibility of police harassment. These leading considerations stymie growth and discourage hiring, along with making major thoroughfares that are trafficked by police a risky place to do business. When asked about the possibility of food-cart street vending becoming legal, nearly 80 percent of vendors said they would expand their business in response. Legalizing food carts is a quick way to jump-start economic growth and innovation across Chicago, especially in minority communities.

More specifically, nearly 2 out of 3 food-cart street vendors said they would increase the number of food carts they operate if vending was made legal.

The overwhelming majority of vendors are Hispanic, meaning Hispanic neighborhoods stand to benefit most from legalization. However, legalizing food carts won’t merely benefit Hispanic neighborhoods. There are other would-be entrepreneurs who are currently sticking to other occupations because of the ban on food-cart street vending. These innovators might bring their culinary talents to bear if City Council passes an ordinance to allow food-cart street vending.

Current economic impact

The economic impact of Chicago’s food-cart street vendors

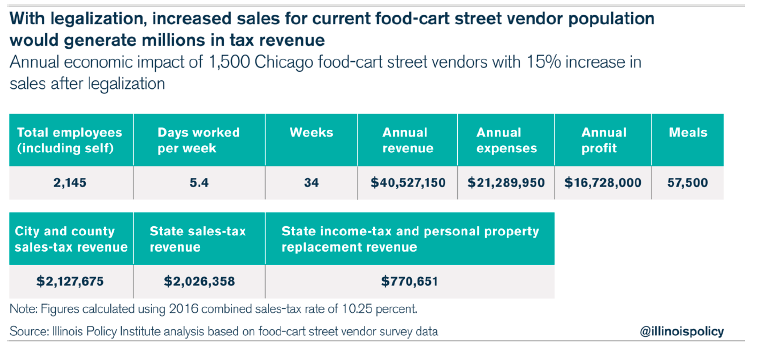

The average Chicago food-cart street vendor generates $691 per week in revenue and spends $363 per week on expenses, earning $328 per week in profits. The average vendor also employs 1.43 people, including him or herself, and works 5.4 days per week.

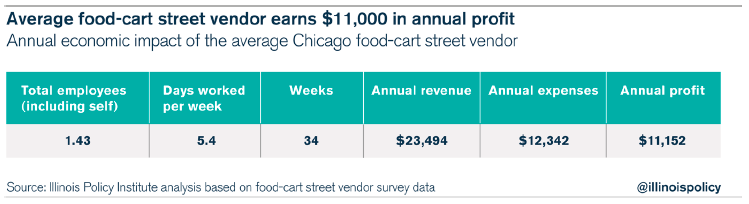

Street vending is a seasonal occupation. Under the conservative assumption that vendors make their regular earnings from street vending for only 34 weeks out of the year, and make no more money from vending during the rest of the year, the average vendor generates $23,490 in annual sales and makes $12,340 in annual purchases, earning $11,150 in annual profits.

The current effect on local tax collections is primarily driven by the vendors’ purchases of food supplies. A local tax of 2.25 percent is levied on unprepared foods in the city of Chicago, which are inputs for food-cart street vendors. Thus, the average food-cart street vendor pays $277.65 per year in local sales tax on food purchases. Because vendors aren’t able to practice their occupation legally, sales-tax compliance on the retail sales they generate is likely low.

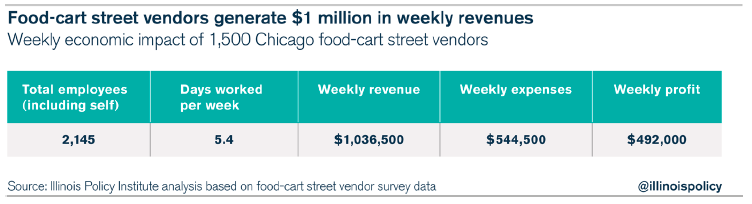

There are estimated to be 1,500 food-cart street vendors in Chicago. In combination, the entire population of street vendors is estimated to generate $1 million in weekly revenues for roughly eight months of the year, while spending nearly $545,000 in expenses, leaving $492,000 per week as earnings.

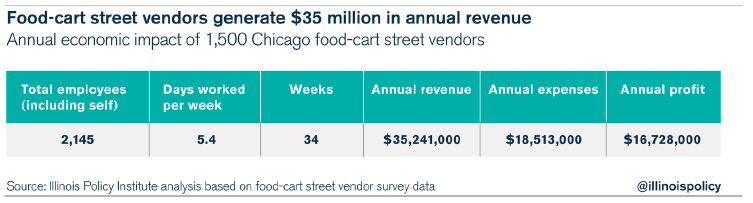

Thus, the entire population of vendors is estimated to generate $35.2 million in annual sales, which cover $18.5 million in annual purchases, leaving $16.7 million in annual profits. This activity generates an estimated $416,543 in annual sales-tax revenue for the purchase of food supplies.

Food-cart street vendors contribute approximately 2,100 jobs to the city, including their own, and as many as 50,000 meals per day for hungry consumers who see food carts as a go-to choice.

Based on other survey indicators, specifically the vendors’ concern about legal problems and police crackdowns, and the vendors’ indication that they would hire and expand if their occupation was legalized, it is likely that these estimates are conservative for what would be achieved by workers who were unencumbered by legal restrictions and police harassment that force them to operate in the shadow economy.

Potential economic impact

The potential economic impact of legalizing food-cart street vending

To estimate the potential economic impact of legalizing food-cart street vending, it is necessary to recognize the two primary limitations that result from current regulations. The first limitation is the lower sales per cart that vendors experience because of forced relocations and concerns about avoiding police and legal repercussions. Nearly 80 percent of vendors say they could expand their business if food carts were legalized and more than 40 percent say they’ve had to move their cart due to law-enforcement harassment.

Surveys indicate that vendors experience a 50 percent decrease in sales when they run into legal troubles and they are constantly worried about ending up on the wrong side of the law, forcing them to expend effort on priorities other than making their business work. In addition, according to the Illinois Policy Institute’s survey, nearly 40 percent of vendors have been ticketed, costing them more in revenue and time from court hearings.

A conservative 15 percent increase in total economic activity would result from legitimizing the vendors and liberating them from concern for legal problems. With the same 1,500 food-cart street vendors, this increase in economic activity would lead to $40 million in total annual sales, $21 million in annual purchases and expenses, $19 million in annual earnings, and $2.1 million in annual sales-tax revenue to the city and county (at Chicago’s 2016 sales-tax rate of 10.25 percent, minus the 5 percent portion reserved for the state). In addition, there would be $2 million in additional state sales-tax revenue along with $770,000 in state income-tax revenue.

However, addressing the increased sales that legalization would allow current food-cart street vendors to achieve only addresses a small part of growth potential. The second and larger limitation on economic growth is on the total number of participants in the street-vendor market that results from fear of legal consequences. Compared to other cities, the stories of police harassment and threat of legal enforcement seems to cause a major bottleneck to growth in Chicago, and street vendors are virtually nonexistent outside of Chicago’s communities of recent immigrants.

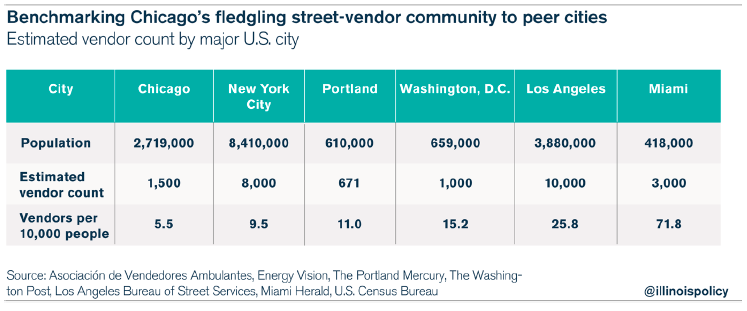

Compared to peer cities for which estimates are available, Chicago has a much lower number of food carts per 10,000 residents. New York City recognizes and licenses some food-cart street vendors, and as a result is generally more hospitable to vendors than Chicago. Energy Vision estimates there are as many as 8,000 mobile food vendors operating in New York City.2 Los Angeles has made several starts at legalizing street vending and is home to a strong Latino community with a cultural affinity to food-cart street vending. Despite LA’s food-cart ban, which is enforced on a complaint basis only, the city has a flourishing food-cart industry. Food-cart street vendors sell across a massive geographical area relatively unencumbered, allowing the trade to grow.3 The Los Angeles Bureau of Street Services estimates there are 10,000 food-cart street vendors in LA.4 The Miami Herald estimates a count of 3,000 street vendors in Miami, where vendors can get a business license but operate under heavy regulations.5 The Washington Post estimates that when Washington, D.C., let street vendors operate relatively unencumbered in the 1990s, there were “thousands” of active vendors in the city.6 Portland is home to an estimated count of 671 food-cart street vendors, who are allowed to operate under strict guidelines after gaining approval from the city.7, 8

If Chicago’s growth potential is anything similar to places where vendors are treated better, then the number of food carts in Chicago could easily grow by multiples. Currently, there are only 5.5 vendors per 10,000 residents in Chicago, compared with 9.5 in New York City, 11 in Portland, 15.2 in Washington, D.C., 25.8 in LA and 71.8 in Miami.

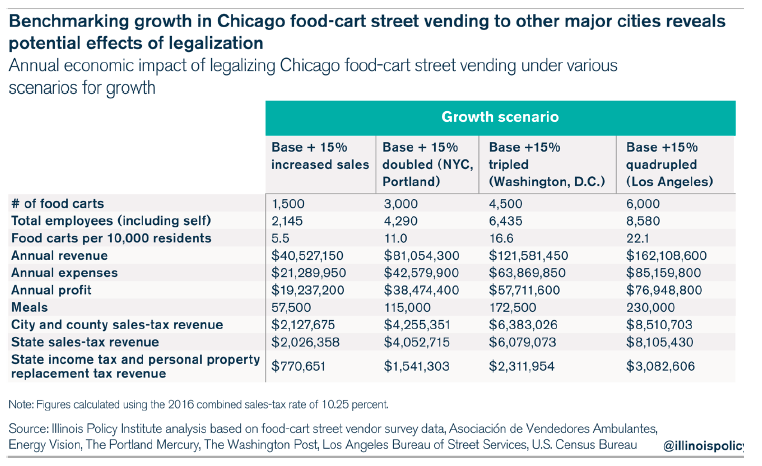

Under a low-end assumption for growth in Chicago, the city would double the number of food-cart street vendors to 11 per 10,000 residents from 5.5 per 10,000 residents. This would put Chicago roughly in line with Portland, Oregon, and New York City in terms of vendors per 10,000 people. With associated economic activity going up correspondingly, the total increase in economic activity would lead to 2,145 additional jobs (4,290 jobs total), $45.8 million in annual sales beyond current levels ($81 million total), $24.1 million in additional annual purchases and expenses ($42.6 million total) and $21.7 million in additional annual earnings ($38.5 million total). Legalization would also drive new tax revenues at the state and local level. Assuming tax compliance, there would be $4 million in new state sales-tax revenues, $4.3 million in new sales-tax revenues for the city and county, and $1.5 million in state income taxes.

A midrange estimate for growth would triple the number of vendors to 16.5 per 10,000 residents from 5.5 per 10,000 residents. This would put Chicago roughly in line with count of vendors per 10,000 residents of Washington, D.C. With all other economic activity going up correspondingly, the increase in economic activity would lead to 4,290 additional jobs (6,435 jobs total), $86.3 million in annual sales beyond current levels ($121.6 million total), $45.4 million in additional annual purchases and expenses ($63.9 million total), and $41 million in additional annual earnings ($57.7 million total). Assuming tax compliance, there would be $6.1 million in new state sales-tax revenues, $6.4 million in new sales-tax revenues for the city and county, and $2.3 million in state income taxes.

A higher-range estimate for growth would quadruple the number of vendors to 22 per 10,000 residents from 5.5 per 10,000 residents. This would put Chicago roughly in line with count of vendors per 10,000 people of Los Angeles. With all other economic activity going up correspondingly, the increase in economic activity would lead to 6,435 additional jobs (8,580 jobs total), $127 million in annual sales beyond current levels ($162 million total), $67 million in additional annual purchases and expenses ($85 million total), and $60.2 million in additional annual earnings ($77 million total). Assuming tax compliance, there would be $8.1 million in new state sales-tax revenues, $8.5 million in new sales-tax revenues for the city and county, and $3.1 million in state income taxes.

Putting it all together

How much Chicago and Illinois are losing out, and what stands to be gained

Current regulations are hurting Chicago residents, whether they are entrepreneurs trying to make a living as street vendors or hungry workers looking for a good meal near their place of employment. The ban on street vendors isn’t stopping vendors, it is simply driving them underground and thwarting their opportunity for growth and expansion. Keeping food carts illegal dramatically harms the well-being of vendors, especially in immigrant communities. The total loss due to current laws, in terms of economic growth and human potential, is devastating.

Currently, thousands of jobs and millions of dollars in personal income and tax revenue are being pushed into the underground economy due to Chicago’s ban on food-cart street vending. The estimates on lost potential are as follows:

- $35.2 million in final sales, which would be added to the city and state’s gross domestic product

- $1.8 million in state sales-tax collections from final sales (at 5 percent of total sales)

- $1.5 million in city and county sales-tax collections (at current 4.25 percent of total sales)

- $641,700 in state income-tax collections (a high-end estimate based on income minus individual deductions taxed at 3.75 percent income tax plus 1.5 percent business personal property replacement tax)

However, these estimates understate the true losses in the city of Chicago, because they don’t account for the strong growth that would occur if food carts were legalized. Therefore, estimates on the true loss to the Chicago economy along with lost tax revenue are much higher. The cost of the current law is that the entire industry has been delegitimized, and cannot operate above board. Conservative estimates on these losses are:

- 2,145 to 6,435 total jobs, most of them self-employed vendors

- $40 million to $160 million in final sales, which would be added to the city and state’s GDP

- $19 million to $78 million in personal income

- $21 million to $85 million in purchases from local wholesalers

- $2 million to $8 million in state sales-tax collections from final sales (at 5 percent of total sales)

- $2 million to $8.5 million in city and county sales-tax collections (at next year’s local rate of 5.25 percent of total sales)

- $0.77 million to $3.1 million in state income-tax collections (a high-end estimate based on income minus individual deductions taxed at 3.75 percent income tax plus 1.5 percent business personal property replacement tax)

There are other losses that cannot be easily quantified. One indirect loss is the knock-on effects of economic growth that would occur based on the increased income and spending from growth in the street-vending sector.

Perhaps most powerfully, legalizing food carts would allow immigrant children to see their parents succeed in Chicago through hard work and long hours. It would teach children of street vendors that if they work hard and do things the right way, Chicago is a great place to pursue their American dream.

Conclusion

Legalizing food carts will not only provide a powerful economic impact in immigrant communities, it will also legitimize a generation of Chicago entrepreneurs. It will also level the playing field among Chicago’s culinary startups. Food-cart street vending allows an entrepreneur who is short on capital to get started up and on her way to making a positive economic impact.

Based on the results of the Illinois Policy Institute’s survey collection projected onto various scenarios for growth, legalizing food carts would legitimize workers who are already on the job, generating tens of millions of dollars in sales and income, and serving 50,000 meals per day. It would also translate into as much as 6,400 new jobs, $127 million in additional new retail sales, $60 million in additional income, $8.5 million in state sales-tax collections, $8.5 million in city and county sales-tax collections, $3 million in additional state income taxes, and 180,000 additional meals served every day. This will make culinary startups more likely to remain in Chicago, and immigrant communities more likely to want to call Chicago home. It will enhance Chicago’s reputation as the fun, flavorful, dynamic city that it has become known to be.

The city of Chicago and the state of Illinois have faced more than a decade of economic headwinds, with more people leaving the state and fewer coming in. Public policy can help change that, one legalized dream at a time. Chicago’s City Council can kick off a new wave of prosperity by enacting policy changes, and start by securing the future of Chicago’s most recent wave of immigrant entrepreneurs.