Bureaucrats over classrooms: Illinois wastes millions of education dollars on unnecessary layers of administration

By Orphe Divounguy, Adam Schuster, Bryce Hill

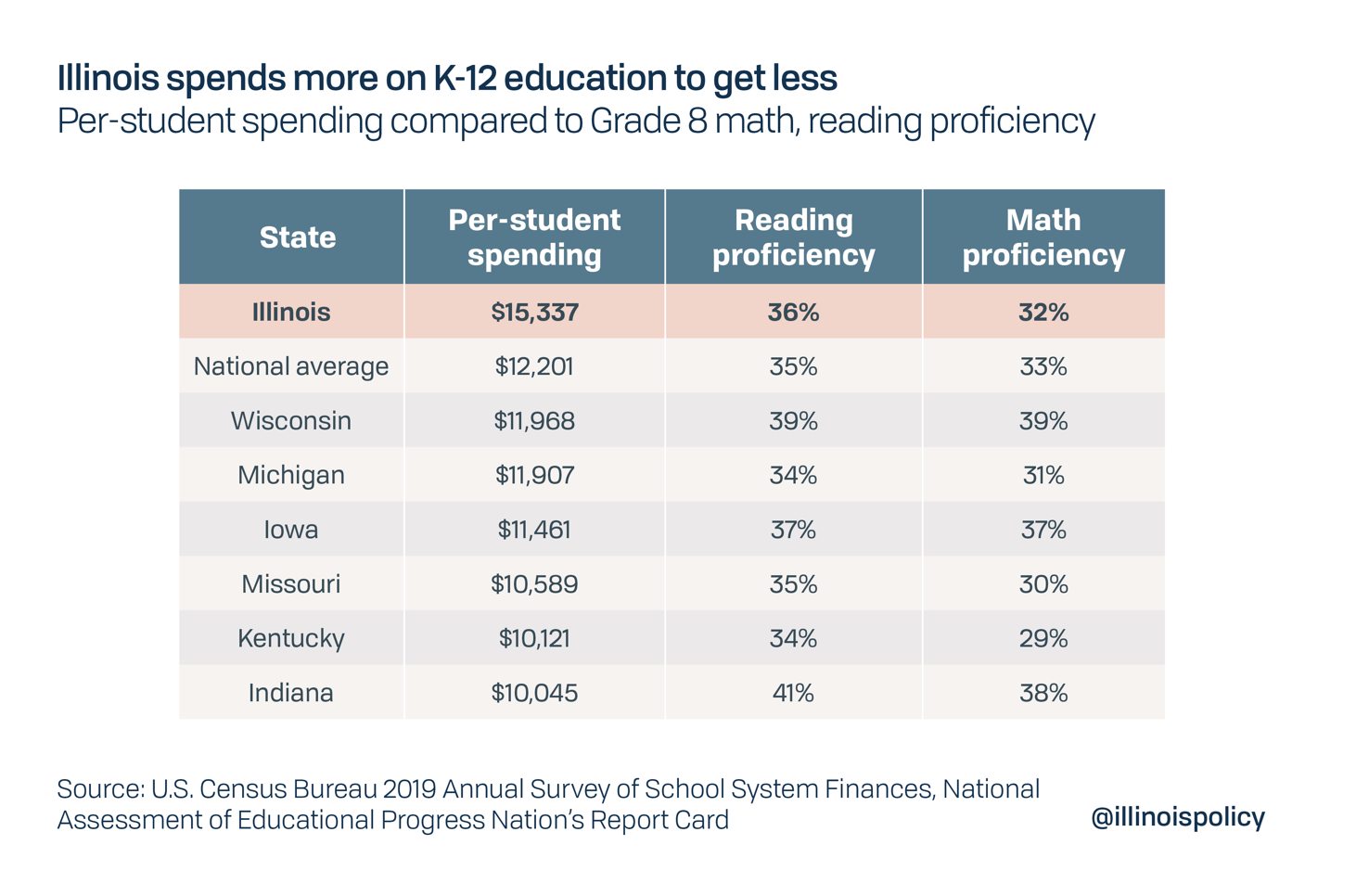

Illinoisans face the second-highest property tax rates in the nation, with the bulk of those taxes going to schools. They spend among the most per student in the Midwest on education, but student outcomes lag many of the state’s neighbors.

Why? Too many education dollars get trapped in bureaucracy before reaching the classroom. In the past four years, Illinois public schools employed fewer teachers and had fewer students, but the number of administrators grew.

Illinois spent $8.4 billion on public education in its fiscal year 2019 budget, not including pension costs for the Teachers’ Retirement System. Too much of that money is propping up a system with 852 school districts – one of the nation’s highest counts. Staffing those districts are over 9,000 school administrators who in 2017 earned over $100,000 per year, and they’ll each receive $3 million or more in pension benefits during their retirements.

The problem is Illinois puts its money into too many administrators running too many school districts. By consolidating school districts without closing schools, Illinois can improve college readiness and save taxpayers money. If Illinois pursued reforms suggested by the Metropolitan Planning Council, and reduced general administration spending to the national average, Illinois could save $708 million annually – double the new money put towards education when the school funding formula was rewritten in 2017.

Top dollar yields lukewarm student results

Illinoisans endure the second-highest property tax rates in the nation. In exchange for exorbitant tax rates, residents expect high-quality public services that will improve the value of their communities and provide greater opportunities for their children. However, while nearly two-thirds of Illinois’ property tax dollars go to pay for public education, and Illinois spends more than all neighboring states and the national average on education, schooling outcomes remain average.

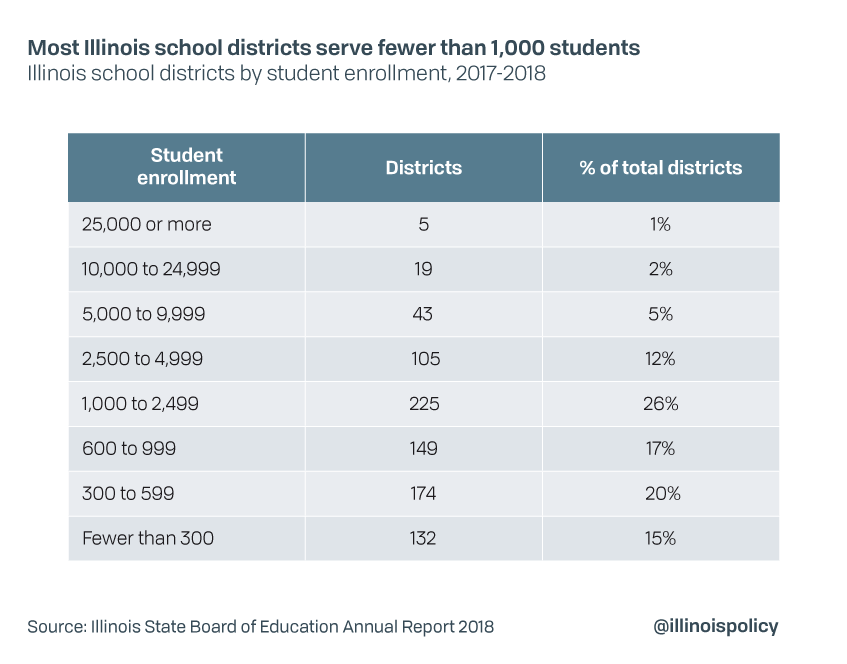

At 852 school districts, Illinois has the fifth-largest number of school districts in the nation. Over half of Illinois school districts serve just 1,000 students, compared with the national average of 3,600 students per district. One in four districts serve just a single school.

The large number of school districts serving relatively few schools and students is a problem that is becoming worse. From 2014 to 2018, student enrollment at Illinois K-12 public school districts fell by 2%, reflected by a nearly identical percentage drop in those districts’ total teachers during that time.

Despite Illinois school districts losing both students and teachers, the number of administrators grew 1.5% during the four-year period.

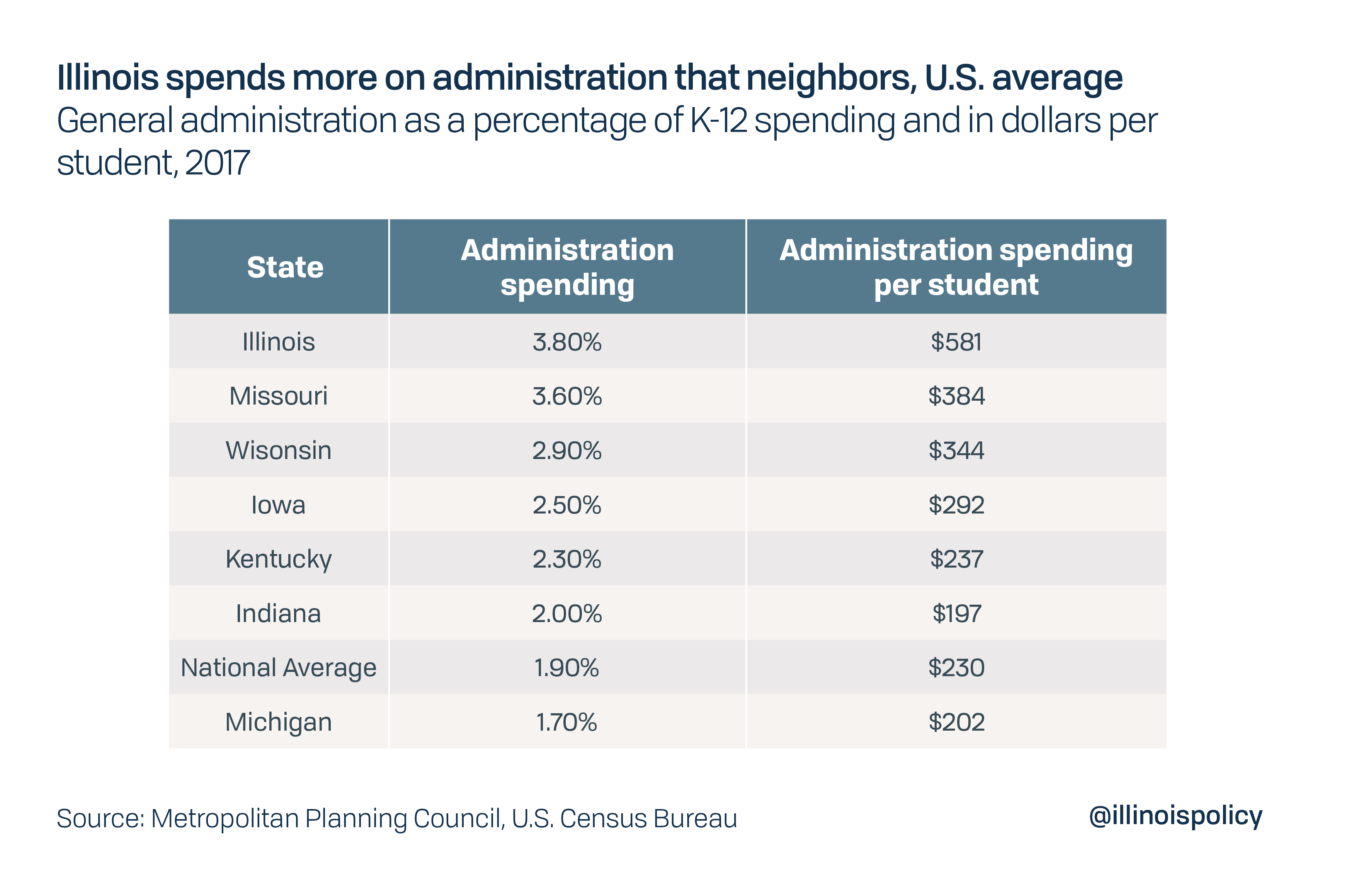

Illinois spends $581 per student on “general administration” costs, which measures spending on school districts but excludes administrative costs within individual schools. That is more than 2.5 times the national average and more than any neighboring state. This excessive spending on bureaucracy keeps money away from students and teachers, where it matters most.

The Metropolitan Planning Council estimated using 2016 Census data that the state could save about $645 million annually if general administration spending were reduced to the national average.1 These savings could result from creating larger school districts, sharing administrative roles such as treasurers or expanding school programs across districts. Since the council’s estimates, new Census data has come out for 2017 that reveal these savings would be even greater at $708 million.2 By comparison, Illinois leaders in 2017 set a target of $350 million in new annual spending in the first rewrite of the state school funding formula in 20 years. It was heralded as a historic, bipartisan effort.

Putting that same effort into school district consolidation could yield double the benefits, plus create better student outcomes. Raising the quality of public education would also boost Illinois property values, which are still far below their pre-recession levels.

Emphasizing schools rather than school districts

Parents prefer certain neighborhoods because of quality public schools. They want small class sizes where their children will receive individual instruction from knowledgeable teachers and be provided with opportunities that will allow them to excel in their future endeavors. These are byproducts of high-quality schools, not of school districts.

While it is challenging to find the perfect balance of class size and resource allocation for any school district, one thing is certain: Increased spending on school district administration does little to improve student outcomes. Instead, investments in the classroom are almost always the best use of education resources to increase student performance.

In order to free up the resources needed to make these investments and to provide much-needed property tax relief, Illinois should consider consolidating its school districts. Consolidating school districts does not mean closing schools. It is a simple way for school districts to benefit from economies of scale and to prioritize students over administration. By combining districts, or forming new larger ones, Illinois can eliminate many costly and excessive positions such as superintendents and reduce overhead costs by owning and operating fewer district offices.

One in four Illinois school districts serve just a single school, so there is significant potential to combine districts and share administrative functions. At the same time, the number of schools could remain unchanged, with the savings from school district consolidation going directly toward classrooms or property tax relief.

What are the effects on student achievement?

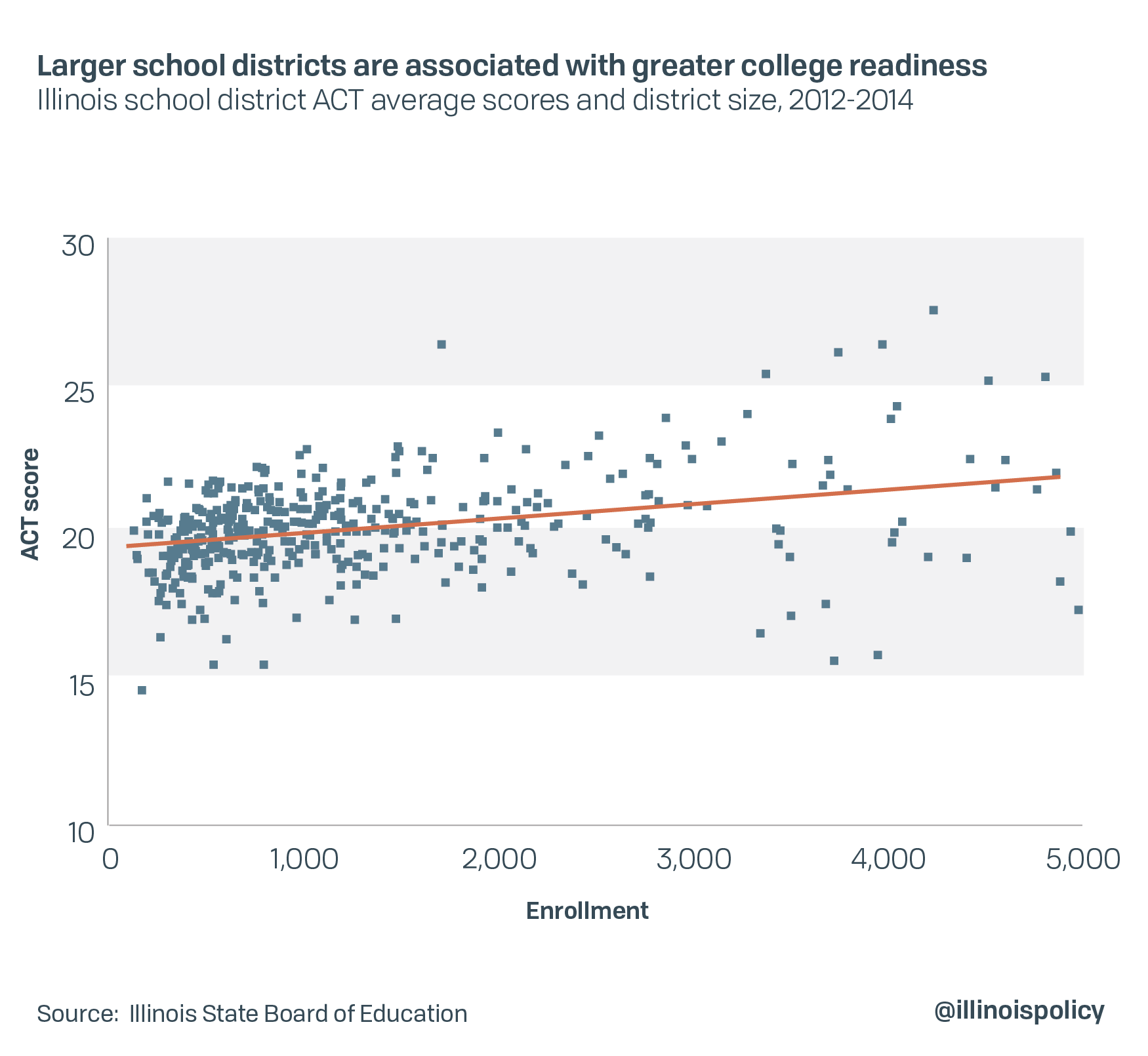

The relationship between Illinois’ school district size and student outcomes – measured in average ACT scores – is clear: larger school districts often yield higher student performance and better college readiness (see Appendix).

To put these results in context, compared with a school district that serves only 300 students with an average composite ACT score of 21, a school district with 1,000 students is likely to have an average composite ACT score of 23, despite similar geographic location, student population demographics and state aid per student.

While this study finds evidence that ACT scores are higher for larger districts, Devaraj, Faulk and Hicks (2018) find that this positive relationship also holds for other standardized test scores in Indiana. In Illinois there appears to be no correlation between other standardized test scores and district size, perhaps because the state has changed testing formats several times in recent years.3,4

In Illinois, a 10% increase in student enrollment is associated with a 0.04 to 0.06-point higher composite ACT scores on average. The results are more extreme for smaller school districts. For districts with fewer than 1,000 students, a 10% increase in district size is associated with up to a 0.09-point higher average composite ACT scores.

These results match what the bulk of the expert literature has to say on the subject. Most experts agree that so long as school district consolidation does not result in school consolidation and longer transportation times, the relationship between school district size and student performance is positive.5

Studies also find larger districts may have a greater quantity and diversity of instructional resources.6 Because larger school districts have larger budgets, they generally spend less on administrative areas, meaning they can spend more on instruction and enrichment programs. For example, a larger school district could more easily recruit an AP math teacher who has more education and requires a higher salary. If needed, the district could even share the teacher between its schools. A smaller district may not be able to find a qualified teacher and then would not be able to offer its students advanced math.7 Unlike schools, school districts can be organized in a variety of ways. The organizational structure of the school district changes many environmental factors at the schools that affect student achievement.8 District size is one of the factors that determines the district’s organizational structure. Larger districts tend to be organized in a way that is more conducive to student success.

Using Indiana school district data, Devaraj, Faulk and Hicks (2018)9 find that, after controlling for income, student demographics and state aid, school district size plays a significant role in student performance. They find that increasing the size of small districts to around 1,000 students increases the average student’s performance on the SAT by 48 points; biology ECA pass rates by 10 percentage points and ISTEP eighth grade pass rates by 8 percentage points. Increasing the size of school districts to 2,000 students can further increase SAT scores by an additional 15 points, increase ACT scores by 0.85 points and pass rates on AP exams by 14.5 percentage points. The evidence also suggests that school districts that serve 4,000 students see a larger share of students earning honors diplomas.

Potential effects on property taxes and home values

Too many districts with too many administrators increase local costs and help explain why Illinois is home to some of the highest property taxes in the nation. Gov. J.B. Pritzker commissioned a property tax task force to dig into solutions to Illinois’ excessively expensive property taxes. Two-thirds of property taxes go toward education, and so education spending must be part of that conversation.

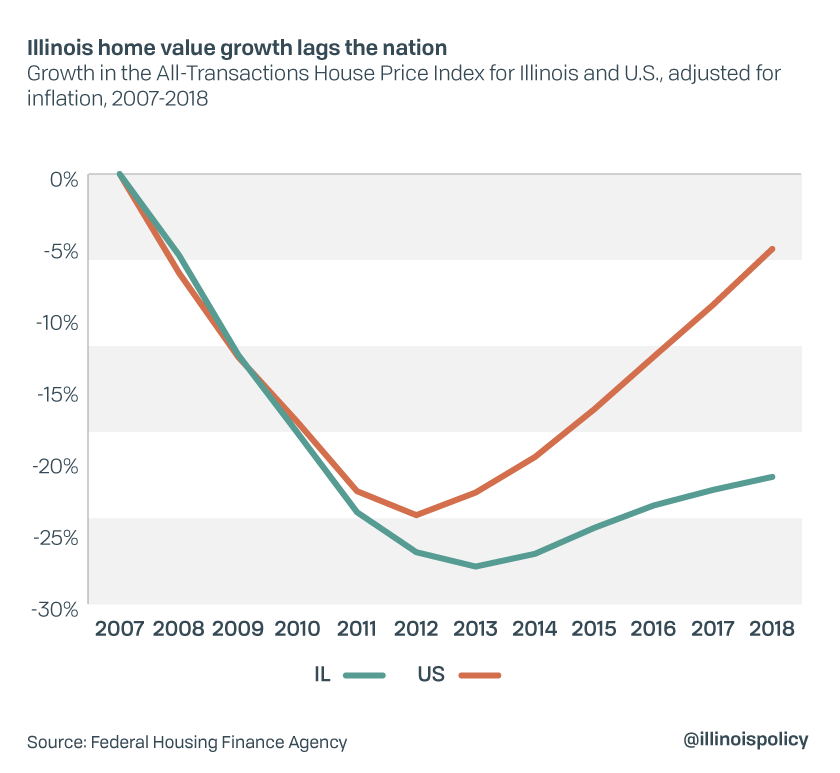

During the past decade, home values in Illinois have dropped by 21%. Meanwhile, property taxes have grown 9%.

The recovery of home prices in Illinois is more painful compared with the national recovery. Since 2007, the decline in home values remains 300% worse in Illinois than the national average – with homeowners nationwide seeing property values just 5% lower today on average than they were in 2007.

The dependence of local governments – primarily school districts in Illinois – on property taxes has been traditionally justified with the claim that an increase in the tax rate has little to no detrimental effect on the tax base. One explanation offered for why property taxes may not lead to changes in property values is that taxes are used to finance public services that may benefit homeowners and businesses. When property ownership is related to individuals’ use of public services, e.g., better policing and better schools, then property taxes can be justified as user fees, implying it is the provision of amenities, not property taxes, that lead to changes in property values.10,11,12,13

However, despite facing such high tax rates and high spending on education, outcomes in Illinois lag those of similar states.14 Part of the reason is because Illinois spends an excessive amount of money maintaining an abnormally high number of school districts. Operating the state’s 852 school districts drives up property taxes and takes money from classrooms, harming students, taxpayers and home values. In cases where property taxes are disproportionately high compared with the quality of the services they fund, home values are negatively affected by increases in property taxes. This has happened in many Illinois communities.15,16

School district consolidation has the ability to promote higher quality education and boost student outcomes while saving taxpayer dollars. This reduced price could be used to deliver property tax relief for Illinoisans, who face the second-highest property tax rates in the nation. At the same time, improvements to the quality of public education would also likely stimulate the appreciation of residential home values, further reducing the burden of property taxes on homeowners.

How can Illinois achieve the benefits of greater efficiency in school districts?

Consolidating school districts is an easy way to improve the quality of education and save taxpayers money. It requires no reduction in either the number of schools or teachers. It could take the same form as House Bill 305317 which passed out of the Illinois House of Representatives in a 109-0 vote18 during the 101st General Assembly. The bill was never given a full Senate vote.

More than 400 school district administrators across Illinois filed witness slips in opposition to HB 3053. Over 130 of those administrators collected six-figure taxpayer-backed salaries, as of May 13.

In total, more than 9,000 top school administrators in 2017 earned more than $100,000 per year. During retirement they’ll each receive $3 million or more in pension benefits. While school districts pay administrators’ salaries and benefits through local property taxes, state taxpayers are on the hook for those pension costs.

HB 3053 would have created the School District Efficiency Commission, tasked with reviewing the state’s 852 school districts,19 which together consume nearly two-thirds of property taxes collected in Illinois. The commission would then make recommendations for consolidating districts, with the goal of reducing the number of districts by a minimum of 25 percent.

The commission’s district reduction goal would not force any individual district to consolidate. Rather, its recommendations would go directly to voters in the various school districts as a ballot question, allowing parents, teachers and local taxpayers living within each school district to determine what is right for the students in their communities.

Finally, the bill would require all newly formed districts to be unit districts, meaning they’d serve both high schools and elementary schools. Data from the Illinois State Board of Education shows unit districts are the most efficient in terms of spending per student.20

Conclusion

By pursuing reforms such as the ones laid out in House Bill 3053,21 the state can prioritize classrooms over bureaucrats. The bill would allow for consolidation – if approved by voters within the affected districts – that would not require altering the number of schools or cutting teachers. Instead, the bill would allow school districts to benefit from economies of scale by pooling their resources, allowing for savings that could be passed on to taxpayers or re-invested in the classroom. School district consolidation has the potential of boosting teacher pay, to improve teacher quality and student performance.

If the Metropolitan Planning Council’s target could be achieved, then reaching the national average for administrative spending would provide at least $708 million a year to help classrooms and property taxpayers. That would be a significant boost, doubling the new dollar target of the new school funding formula.

Illinoisans pay large sums for public education, yet a large portion of the money goes to Illinois’ bloated school district bureaucracy that diverts resources away from the classroom. Through smart, strategic reforms, Illinoisans can better prepare their youth for the future as well as provide property tax relief.

Endnotes

- Ibid.

- Adam Schuster, “More efficient school administration could maximize student potential,” Springfield State Journal-Register, August 27, 2019.

- Diane Rado, “Spring State Testing Season Brings Changes, Unknowns, and Pushback,” Chicago Tribune, March 7, 2016.

- Kate Thayer, “Illinois Scraps Controversial PARCC Test in Favor of Shorter Exam with New Name,” Chicago Tribune, March 6, 2019.

- Andrews, Matthew, William Duncombe, and John Yinger, “Revisiting economies of size in American education: are we any closer to a consensus?,” Economics of education review 21.3 (2002): 245-262.

- Bidwell, Charles E., and John D. Kasarda. “School district organization and student achievement.” American Sociological Review (1975): 55-70.

- Devaraj, Srikant, Dagney Faulk, and Michael Hicks, “School District Size and Student Performance,” Journal of Regional Analysis & Policy 48.4 (2018): 25-37.

- Bidwell and Kasarda, “School district organization and student achievement.”

- Devaraj, Faulk and Hicks, “School District Size and Student Performance.”

- Dennis Carlton, “Why New Firms Locate Where They Do: An Econometric Model,” Interregional Movements and Regional Growth (Washington D.C.: The Urban Institute, 1979).

- Timothy Bartik, “Business Location Decisions in the United States: Estimates of the Effects of Unionization, Taxes and Other Characteristics of States,” Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, no.3 (1985).

- Ronald C. Fisher, Timothy J. Bartik, Harley T. Duncan, Therese McGuire, and Robert M. Ady, “The effects of state and local public services on economic development,” New England Economic Review (1997): 53.

- M. Wasylenko, “Taxation and economic development,” New England Economic Review (March/April 1997): 37-52.

- Bryce Hill and Joe Tabor, “Illinois Spends More on Education, but Outcomes Lag,” Illinois Policy Institute, February 25, 2018.

- Bryce Hill, “Cook County Home Values Down 31%, Property Taxes Up 22% since 2007,” Illinois Policy Institute, August 6, 2019

- Orphe Divounguy and Bryce Hill, “Illinois Home Values Down 21%, Property Taxes Up 9% Since 2007,” Illinois Policy Institute, July 19, 2019.

- Illinois 101st General Assembly, Illinois House Bill 3053

- Illinois 101st General Assembly, House Roll Call, House Bill 3053

- Illinois State Board of Education, “School District Reorganizations 1983-84 to 2018-19,” July 2018

- Adam Slade and Nick McFadden, “How Can Illinois School Districts Address Funding Woes? Share Administrative Services,” Metropolitan Planning Council, April 7, 2019.

- Illinois 101st General Assembly, Illinois House Bill 3053