Asset forfeiture in Illinois: What it is, where it happens, and reforms the state needs

By Ben Ruddell, Bryant Jackson-Green

Most people expect Illinois law enforcement to defend the private property of Illinois residents. As long as you obey the law, your life, liberty and property should be secure from the law – or so common sense would suggest.

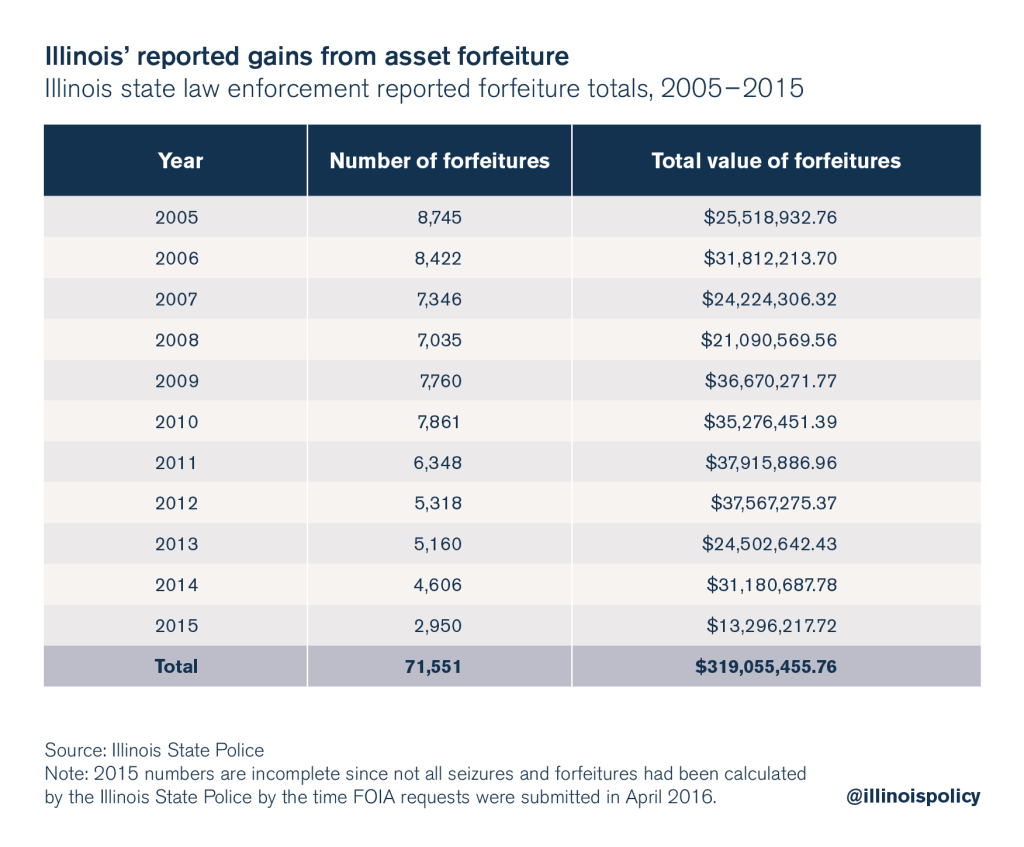

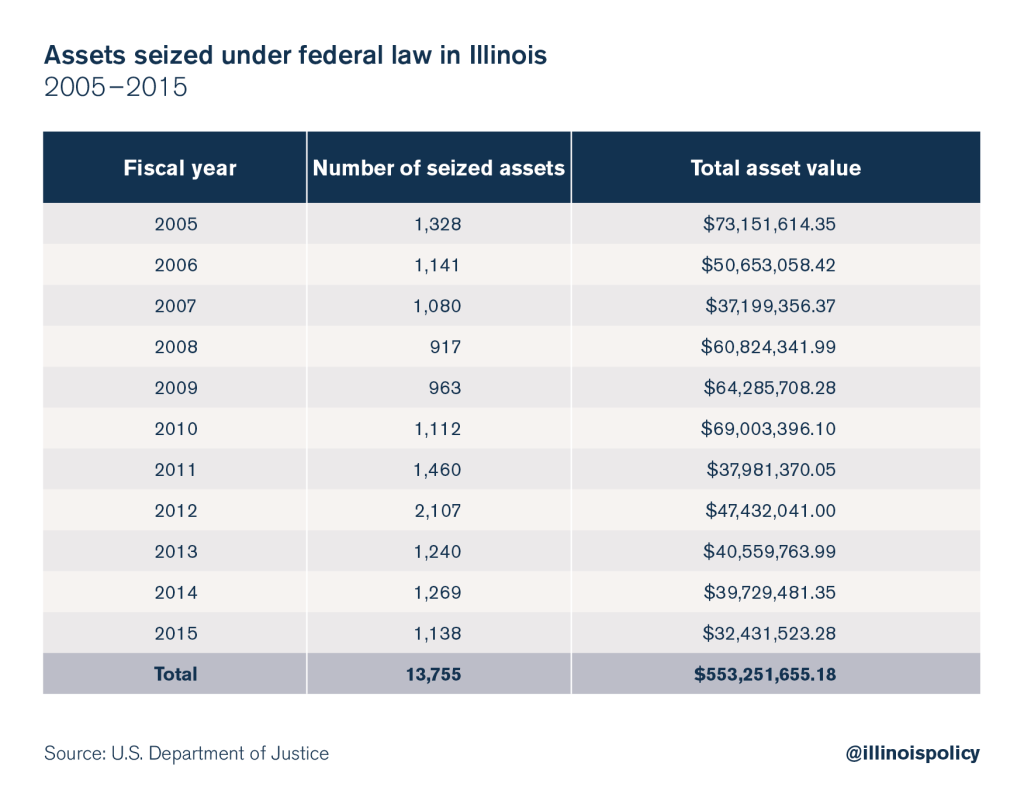

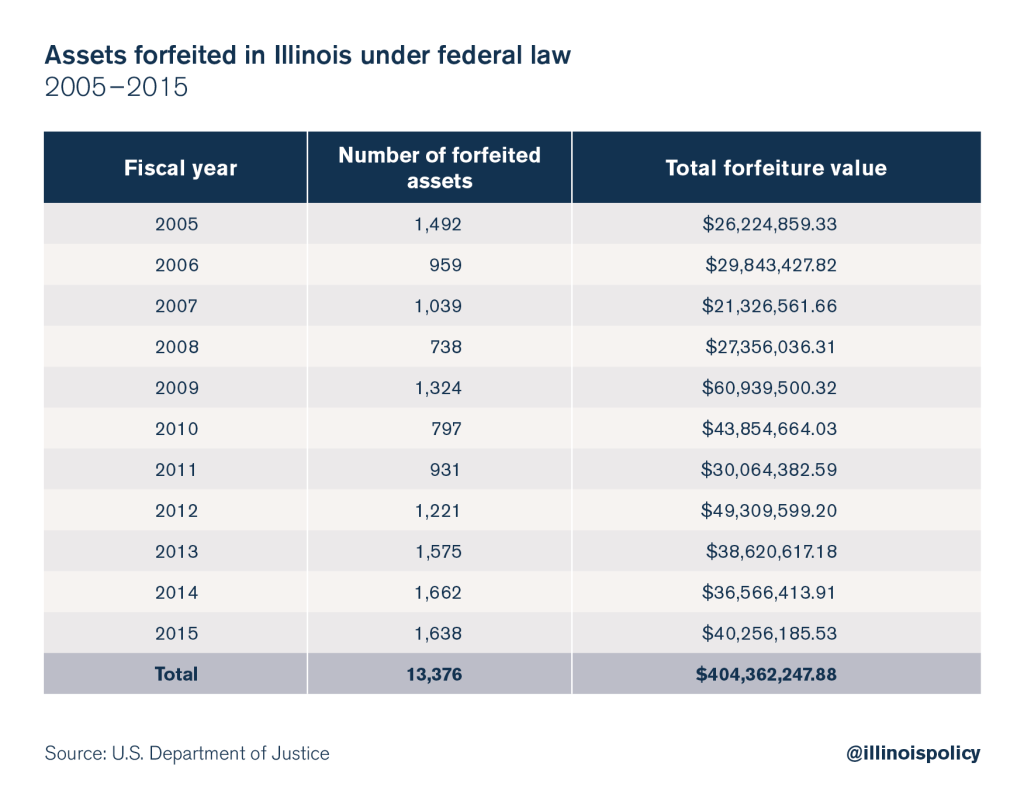

Yet, every year, Illinois law enforcement agencies take tens of millions of dollars in cash, vehicles, land and other assets from state residents – in some cases without bringing criminal charges, let alone obtaining convictions, against property owners. Asset forfeiture laws, which allow the confiscation of private assets suspected of involvement in illegal activity, have been subject to abuse – and have produced large payouts for law enforcement. Since 2005, Illinois has pocketed more than $319 million from private citizens throughout the state.[1] Federal law enforcement took in more than $404 million in Illinois over the same time period.[2]

While forfeiture is lucrative for law enforcement, it can be devastating to the people from whom property is taken. Motor vehicles, because of their high value, have become particularly popular targets of seizures. But losing a vehicle even temporarily can precipitate a cascade of negative consequences in a person’s life, including the inability to maintain employment or even to attend court proceedings to try to reclaim the seized property. This practice can exacerbate impoverishment and harm the person’s innocent children and family members.

Exactly how much is gained by Illinois law enforcement through asset forfeiture, and which agencies are responsible for the bulk of asset seizures? And what can be done to ensure property owners face a fair, efficient and equitable process when their property is seized?

New research from the Illinois Policy Institute and the American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois answers these questions. Drawing on data from Freedom of Information Act requests to Illinois State Police and the U.S. Department of Justice, this report sheds light on how much specific law enforcement agencies are taking in Illinois under state and federal asset forfeiture laws. This report finds:

- Between 2005 and 2015, forfeiture proceedings have resulted in gains of more than $319 million for Illinois police departments, sheriffs, state’s attorneys and other law enforcement agencies.

- Most asset seizures take place in Cook County, followed by Lake, Will, Rock Island, Macon and Winnebago counties – but millions more dollars’ worth of property have been seized by jurisdictions throughout the state.

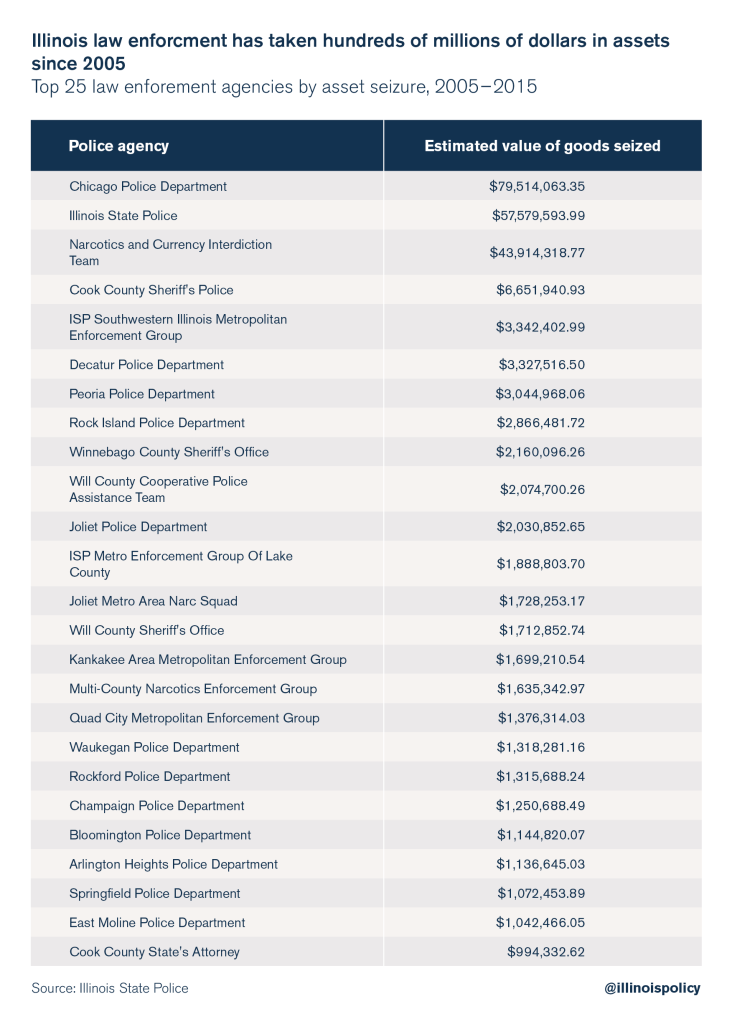

- The law enforcement agencies making the most seizures are the Chicago Police Department, the Illinois State Police, the Narcotics and Currency Interdiction Team, the Cook County Sheriff’s Office and the Decatur Police Department.

This report recommends policy reforms in three areas to better protect the rights of innocent property owners:

- Provide fair legal standards and procedures in forfeiture cases: Illinois forfeiture laws should require a criminal conviction before property can be forfeited to the government. The burden of proof in a forfeiture action should rest squarely upon the government and should be raised to require clear and convincing evidence. The practice of “nonjudicial” forfeiture, where property may be forfeited without a judge’s consideration of the merits of the case, should be eliminated. The law should require that civil forfeiture proceedings be instituted against the property owner rather than against the property itself, and all known owners of seized property should be named in the complaint and served with process. Finally, lawmakers should eliminate the requirement for the owner to post a cash bond for the right to challenge a forfeiture in court.

- Remove incentives to engage in “policing for profit”: Any property gained by the government through forfeiture should be auctioned and the proceeds deposited directly into the general revenue fund and appropriated by the General Assembly rather than being awarded directly to police and prosecutors’ offices. Illinois law enforcement agencies should be restricted from participating in federal equitable sharing programs so they cannot circumvent reforms to state forfeiture law and procedures.

- Increase transparency about how forfeiture funds are acquired and used: Law enforcement agencies and prosecutors’ offices should be required to publicly report information about how much property they seize, where and when the seizures took place, the outcome of all forfeiture cases, and how they spend any forfeiture proceeds.

Forfeiture is a powerful tool – far too powerful to allow governments to wield it with little public oversight or accountability. Lawmakers need to adopt meaningful asset forfeiture reforms to better protect the rights and property of Illinois residents.

[1] Information received from Illinois State Police pursuant to Freedom of Information Act 2016 request.

[2] Information received from U.S. Department of Justice pursuant to Freedom of Information Act 2016 request.

Introduction

Asset forfeiture is the permanent confiscation of private property by law enforcement agencies at the local, state and federal levels. Illinois and federal law both permit law enforcement agencies to take cash, land, vehicles and other property they suspect is involved in or derived from illegal activity.

From 2005 through 2014, approximately $31 million a year on average was extracted from Illinoisans through forfeiture on the state level – and that number doesn’t even include additional “Article 36” vehicle forfeitures, potentially numbering in the thousands annually, that are never reported.[1] An average of more than $36 million more was seized each year in Illinois under federal law. Illinois stands out among other states for its high seizure rates, ranking among the top 11 in takings through equitable sharing with the federal government.[2]

American forfeiture laws originated from admiralty and customs laws, which allowed seizure of contraband from ships at sea. However, the practice remained relatively obscure until the “War on Drugs” of the 1980s and 1990s. The Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 expanded civil forfeiture at the federal level[3] and inspired states to enact their own forfeiture laws.[4] By “removing the proceeds of crime and other assets relied upon by criminals and their associates to perpetuate their criminal activity against our society,” it’s reasoned, law enforcement would have another tool to “disrupt or dismantle” criminal organizations, including but not limited to drug dealers.[5]

But despite good intentions, asset forfeiture has proved subject to abuse.

Civil asset forfeiture litigation is brought not against a person, but against his or her property when the property is suspected of being involved in illegal activity. But the law offers little protection for property owners. Under Illinois law, a person need never be convicted of any crime – or even arrested or charged – in order to be permanently deprived of cash, a car, or even a home. And regardless of whether the person from whom property is seized is ever charged with a crime, he or she has no right to appointed counsel in a forfeiture proceeding.

Law enforcement agencies have a strong financial incentive to seize property, because they reap almost all of the proceeds from civil asset forfeiture. Once police seize property on the suspicion that it is connected to a crime, the burden of proof is essentially on the owner to prove that the property should not be permanently forfeited to the government – if he or she can afford to challenge the taking at all. Some of Illinois’ laws even force property owners to pay up front for the right to challenge the forfeiture in court. The high cost of challenging a seizure, and the fact that many who face seizure of their property cannot afford private legal representation, means that innocent people can be effectively denied access to justice.

One especially egregious example comes from the Quad Cities. In August 2015, Judy Wiese, then 70 years old, received an unwelcome lesson about Illinois forfeiture laws after her grandson borrowed her 2009 Jeep Compass to drive to work. While he assured her that he had fulfilled his legal obligations arising from a prior DUI, in fact Judy’s grandson’s driving privileges were still suspended, and that night he was arrested, and the vehicle was seized. Subsequently, the prosecutor’s office instituted a forfeiture action to take the vehicle away permanently. For more than five months, Wiese pleaded for the return of her vehicle and tried in vain to complete the legal paperwork required to contest the attempted forfeiture. During this time, without transportation, she was unable to attend therapy appointments for her broken arm, or even to make trips to the grocery store without help from friends.[6]

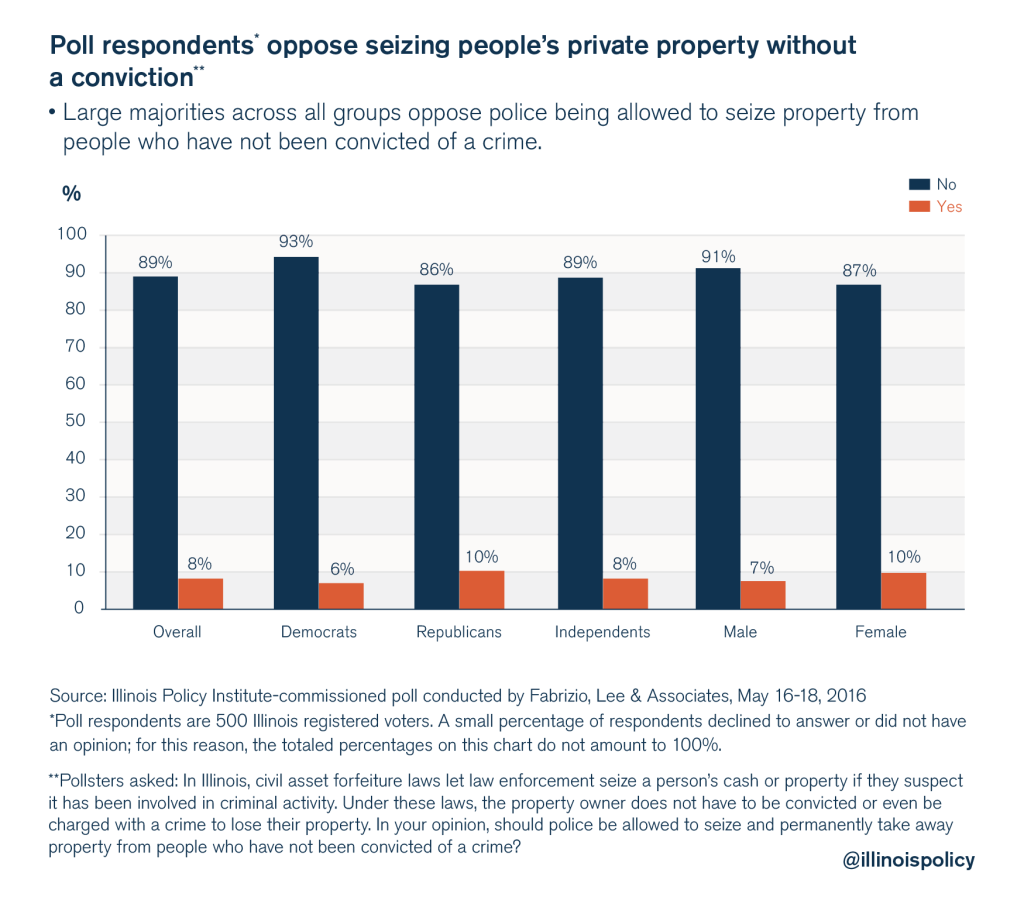

Judy Wiese is just one of many innocent people across the country who have suffered under asset forfeiture laws – and voters are beginning to take notice. A May 2016 poll of Illinois registered voters commissioned by the Illinois Policy Institute showed an overwhelming majority of poll respondents are skeptical of civil asset forfeiture.[7]

One question asked, “In Illinois, civil asset forfeiture laws let law enforcement seize a person’s cash or property if they suspect it has been involved in criminal activity. Under these laws, the property owner does not have to be convicted or even be charged with a crime to lose their property. In your opinion, should police be allowed to seize and permanently take away property from people who have not been convicted of a crime?”

The response was negative across all political affiliations: 89 percent of registered voters opposed property seizures without a conviction. This includes 93 percent of Democrats, 86 percent of Republicans and 89 percent of Independents.

Having heard about instances of forfeiture abuse in Illinois and nationally, voters are ready for reform. This paper examines the state of forfeiture law in Illinois, how much property Illinois law enforcement agencies seize through asset forfeiture and where, and suggests a path to reform.

What is asset forfeiture?

Asset forfeiture is the legal process by which the government may permanently confiscate a person’s property.

Property may be subject to forfeiture under federal or state law if it is suspected to be either the proceeds of a crime or an “instrumentality” of a crime (used or intended for use in the commission of a crime). Practically any type of property may be forfeited, including cash, a vehicle, personal property, or even real estate.

Seizure of property occurs when the police or another arm of state or local government takes custody of private property, and is generally authorized whenever an officer has probable cause to believe that the property was derived from, or used in the commission of, a crime.

After seizure, the government may seek forfeiture of the assets; in a judicial or quasi-judicial forfeiture proceeding, the government seeks to permanently deprive a person of the property. If the government succeeds in the forfeiture action, then legal title to the property will be transferred from the property owner to the government.

Criminal forfeiture laws provide that forfeiture proceedings are part of, or ancillary to, a criminal prosecution, often before the same judge and jury, and require the defendant to be found guilty of the charged offense beyond a reasonable doubt before the court orders the forfeiture of property.[8]

In contrast, civil forfeiture laws allow the government to pursue a civil action to take away a person’s property regardless of whether the owner or any other person is criminally prosecuted.[9]

Some states, but not Illinois, have adopted a hybrid approach, allowing property to be forfeited in a civil rather than a criminal proceeding, but requiring that, before property can be permanently forfeited to the state in the civil proceeding, the owner or another person must have been convicted of a criminal offense.[10]

Civil asset forfeiture proceedings may be in personam (“directed toward a particular person”) or in rem (“against a thing”). Outside of forfeiture cases, most civil actions in American courts are in personam: lawsuits filed against a specific person or persons, who must be joined as parties and served with a summons and complaint to give the court jurisdiction to try the case.[11] Any judgment entered in an in personam action applies only to the defendant, and may be enforced anywhere that he or she may be.[12]

In personam is distinguished from in rem jurisdiction, in which the “defendant” is one or more pieces of property. A judgment in rem operates directly on the property itself and is enforceable against the world at large.[13] While the law typically requires notice to be sent by mail to known property owners, unlike in most civil lawsuits, owners are not required to be personally served with a summons and complaint to ensure that they do in fact receive proper notice of the action being taken against them.[14]

In jurisdictions authorizing civil in rem forfeiture actions, where the “defendant” is property rather than a person, there is generally no right to appointed counsel, regardless of whether the owner has the financial means to hire an attorney. Federal forfeiture law provides a narrow exception, under which the court has discretion to appoint counsel for a property owner if there is a related criminal matter in which that person is represented by the federal defender. The federal system also gives a person the right to have counsel appointed if he or she is using the property as a primary residence.[15]

Judicial forfeiture proceedings, whether civil or criminal, involve the determination by a judge that the government has met, or has failed to meet, its evidentiary burden of proving that the property is subject to forfeiture under the relevant law.

However, some states, including Illinois, and the federal government, also authorize “nonjudicial” or “administrative” civil forfeitures.[16] In a nonjudicial forfeiture proceeding, the government is never required to present evidence that the property is subject to forfeiture;[17] rather, the property is forfeited by default unless the owner acts swiftly to take the correct legal steps required to contest the forfeiture in court.

Forfeiture statutes generally provide that, in order to prevail in a forfeiture action, the government has the burden of proving that the property at issue either derived from the proceeds of a crime or was used in the commission of the crime. Different forfeiture laws require different standards of proof for the government to meet its burden in a forfeiture case. A commonly used standard in forfeiture cases is preponderance of the evidence[18] (the claim is more probably true than not), which is the usual standard for a plaintiff to meet his or her burden in a civil lawsuit. But some laws require only that the government show probable cause that the property in question is subject to forfeiture.[19] Still others require clear and convincing evidence[20] (the claim is substantially more likely to be true than not), or even proof beyond a reasonable doubt.[21]

But, while a few states’ forfeiture laws require the government to prove that the property owner had knowledge of and/or consented to the crime in order to prevail in the forfeiture action,[22] more frequently, forfeiture laws impose a burden upon the innocent property owner to prove that he or she did not know of or consent to the alleged crime in order to avoid losing the property.[23]

Forfeiture laws also vary as to what becomes of property after it is declared forfeited by a court. Usually the property is to be sold at auction, after which the proceeds may be deposited into law enforcement budgets (as in most states, including Illinois),[24] general revenue funds,[25] or diverted to one or more special-purpose funds,[26] depending on the requirements of the relevant statutes.

Frequently, forfeiture statutes set forth a formula for distributing the sales proceeds to ensure that the money derived from forfeiture will primarily or exclusively benefit the law enforcement agency that seized the property, and/or the prosecutor’s office that instituted the forfeiture case.[27] Some laws allow the seizing law enforcement agency to keep the property itself (e.g., vehicles, electronics, firearms) for its own use instead of selling it at auction.[28]

State and local law enforcement authorities also seize property in cooperation with the federal government, through a process called equitable sharing. The Department of Justice’s equitable sharing program allows local and state police to collaborate with federal law enforcement so that any property taken will be forfeited under federal law, bypassing state forfeiture laws. Local agencies may keep up to 80 percent of these forfeited funds.

Property may be subject to equitable sharing if it is seized by a joint task force that includes both federal and state or local officers, or if it is seized as part of a joint investigation by federal and state or local authorities. Federal agencies can “adopt” property seized by state authorities, and local law enforcement can turn over property they seize for forfeiture under federal law, as long as federal law authorizes forfeiture based on the conduct giving rise to the seizure.[29]

How does asset forfeiture work in Illinois?

Scope of forfeiture laws

Currently, there are numerous laws throughout the Illinois Compiled Statutes that pertain to forfeiture. These include:

- Forfeitures in connection with suspected drug violations

Forfeiture is authorized for property derived from or used in the commission of any violation of the Illinois Controlled Substances Act or the Methamphetamine Control and Community Protection Act, including the simple possession (no intent to deliver) of any quantity of a controlled substance[30] or methamphetamine.[31] Forfeitures based on cannabis offenses are limited to felony violations (simple possession of more than 100 grams of cannabis, or possession with intent to deliver more than 10 grams of cannabis).[32] Forfeiture is also authorized on the basis of a violation of the “legend drug” prohibition under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act.[33]

The Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act sets forth the procedures for civil forfeitures authorized under the above-mentioned drug statutes.[34]

- “Article 36” forfeitures of vehicles, vessels and aircraft

Article 36 of the Illinois Criminal Code[35] authorizes seizure and forfeiture of a vehicle, vessel or aircraft on the basis of the property allegedly having been used in the commission of any of a long list of assorted crimes, including driving offenses such as DUI or driving on a suspended license, violent crimes such as murder and rape, certain firearms offenses, and several property crimes.[36]

The statute also sets forth the procedures for seizures and forfeitures of property under Article 36.

Several other statutes that authorize seizure and forfeiture of property (including, in some cases, other types of property besides vehicles, vessels and aircraft) explicitly provide that forfeiture under those statutes shall happen in accordance with the procedures set forth in Article 36.[37]

- Forfeitures under the money laundering law

Article 29B of the Illinois Criminal Code is Illinois’ money laundering law.[38] The statute authorizes two very different types of litigation: (1) criminal prosecution for the offense of money laundering, which involves conducting financial transactions or transmitting monetary instruments with the intent of furthering or concealing criminal activity; and (2) civil in rem proceedings for forfeiture of property suspected to be the proceeds of money laundering.

While the statute authorizes forfeiture proceedings instituted in connection with a criminal prosecution for money laundering, it also authorizes a civil in rem forfeiture action to be instituted independent of, or even in the absence of, any criminal prosecution.

The provisions of Article 29B setting forth procedures for forfeiture of property also apply in forfeiture cases under the Illinois RICO law[39] and the Financial Aid Fraud law.[40]

- Illinois Street Gang and Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Law

Illinois’ Street Gang and Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Law, or RICO law, allows criminal prosecution of individuals alleged to be participants in certain organized crime enterprises. The RICO law provides that a violation may subject property to seizure and forfeiture, in accordance with the procedures provided under the money laundering law.[41]

- Narcotics Profit Forfeiture Act

This statute provides for criminal forfeiture when a person is convicted of narcotics racketeering. It provides for the forfeiture of any property, profits or proceeds or property interest he or she has acquired or maintained through the violation, and property used to facilitate a narcotics racketeering violation.[42]

- Article 124B of the Illinois Code of Criminal Procedure

Most of Illinois’ criminal forfeiture provisions are consolidated in Article 124B of the Illinois Criminal Code.[43] This law sets forth the legal standards and procedures for seizing and forfeiting property in connection with criminal prosecutions for a wide range of offenses, including child pornography, human trafficking, animal fighting, public assistance fraud, and terrorism.[44]

- Other Illinois statutes authorizing asset forfeiture

In addition to the laws enumerated above, there are numerous other Illinois statutes authorizing the seizure and forfeiture of property on the basis that the property is connected to some violation of the law.[45]

An Illinois civil asset forfeiture case from the property owner’s perspective

The forfeiture process usually begins when property is seized by a police officer who believes the property is involved in criminal activity. The property might be seized directly from the owner, but may just as easily be seized from another person having possession (e.g., a vehicle seized from a family member or friend of the owner).

After the property is seized, the owner has no legal recourse to seek the return of the property until a preliminary hearing at least 14 days after the seizure. If the court finds at the preliminary hearing that the police had probable cause to seize the property, then the person will be required to prepare and file a “verified answer” under penalty of perjury and, in addition to applicable court fees, may even be required to post a cash bond equal to 10 percent of the value of the seized property just for the right to contest the forfeiture. Failure to take these steps will result in the property being forfeited automatically through a “nonjudicial forfeiture.” If the person cannot afford to hire an attorney, then he or she will have to represent himself or herself.

At trial, the government is supposed to prove that the property was involved in a crime – although at no point must it be proved that the owner committed the crime, or even knew about it. Despite the usual rule barring admission of hearsay testimony, the prosecutor – but not the property owner – can admit hearsay evidence in the case.

If the court finds that the state has met its low burden, then the owner is placed in the untenable position of having to prove his or her innocence. To get his or her property back, he or she must somehow “prove a negative” and convince the court not only of the fact that he or she did not commit a crime, but also that he or she did not know and could not have known about the crime.

Even if the owner manages to win the case, he or she will still be responsible for 10 percent of the bond he or she posted for the right to have his or her day in court, and can’t recover attorneys’ fees (in the event that he or she had the resources to hire a lawyer). No additional compensation is available for having been wrongfully deprived of possession of the property, however long it was in the custody of the authorities.

Procedures and legal standards for forfeiture in Illinois

While there is significant variance among Illinois’ numerous forfeiture laws with regard to the procedures and standards that govern different kinds of forfeiture cases, some of the significant features of these laws are described in this section.

Criminal conviction usually not required

Criminal forfeiture in Illinois is the exception rather than the rule. A criminal conviction is required to forfeit property under most provisions of Article 124B of the Illinois Criminal Code,[46] the Narcotics Profit Forfeiture Act[47] and the Public Corruption Profit Forfeiture Act.[48]

However, other Illinois forfeiture laws, including the Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act, money laundering statute and Article 36 of the Criminal Code, do not require a criminal conviction as a prerequisite to forfeiture; in fact, there is no requirement that any person ever be arrested or charged with any offense before the state can take away property through civil asset forfeiture under those statutes and others.

Nonjudicial forfeiture

The Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act and money laundering law each authorize nonjudicial forfeiture. Under those statutes, seized property will be automatically forfeited without judicial involvement unless the owner has, within 45 days of the state sending him or her notice of the proceeding, filed a verified answer with the court and posted a cost bond equal to 10 percent of the value of the seized property.[49]

In drug cases, nonjudicial forfeiture is unavailable if the seized property is real property, or if the seized property (other than a vehicle, vessel or aircraft) exceeds $150,000 in value. In those cases, a hearing is required at which the state must prove its case in order to prevail. Vehicles, vessels and aircraft are subject to forfeiture even if they exceed $150,000 in value.[50]

In money laundering cases, nonjudicial forfeiture is unavailable for real property or personal property exceeding $20,000 in value. Vehicles, vessels and aircraft are excluded and may be the subject of nonjudicial forfeiture irrespective of their value.[51]

Preliminary hearings

In 2012, precipitated by a due process challenge to Illinois drug forfeiture laws,[52] a new law was enacted requiring that seizures under the Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act and under Article 36 shall trigger a preliminary hearing, required to take place within 14 days of the seizure, at which the state must make a showing of probable cause for the seizure to a judge before the case can proceed to a nonjudicial forfeiture. The rules of evidence do not apply in these preliminary hearings.[53]

The money laundering statute, however, was not amended as part of the 2012 reform; no preliminary hearing is currently required by statute in forfeiture proceedings brought under that law.

Cost bonds

Some of Illinois’ forfeiture laws require property owners to post a “cost bond” of 10 percent of the property’s value and to agree to pay all costs and expenses of forfeiture proceedings in the event that the government prevails, in order to have the case heard by a judge. Failure to post the bond will result in nonjudicial forfeiture of the property. Even if the claimant prevails in the forfeiture case, the law provides that the circuit court clerk shall retain 10 percent of the bond amount as “costs.”[54]

Burdens and standards of proof

Most Illinois forfeiture laws at least ostensibly place the burden of proof on the state to prevail in its case in order to prevail in a forfeiture action.[55] But in order to establish a prima facie case for forfeiture, the prosecutor need only show, under very lenient evidentiary standards, that the property itself was probably involved in some violation of the law; the burden of proof then shifts to the owner to either rebut the government’s case or to affirmatively prove his or her own innocence.

The standard of proof that the government must reach in order to meet its burden under many of the state’s forfeiture statutes is preponderance of the evidence.[56] However, in forfeiture cases brought under the Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act,[57] money laundering law[58] and Illinois Street Gang and Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations, or RICO, Law,[59] the standard is merely probable cause.

Innocent owners

While most Illinois forfeiture laws purport to require the state to prove its case to prevail in a forfeiture action, the reality is that, in order to avoid forfeiture of his or her property, an owner who protests that he or she is innocent of any criminal wrongdoing actually has the burden of proving that he or she was innocent. Astonishingly, in some cases, the owner must even prove that he or she could not possibly have known about the alleged wrongdoing.

For example, under the Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act, a property owner facing forfeiture of personal property, in order to successfully assert an “innocent owner” defense, must establish by a preponderance of the evidence that he or she “is not legally accountable for the conduct giving rise to the forfeiture, did not acquiesce in it, and did not know and could not reasonably have known of the conduct or that the conduct was likely to occur.”[60]

While Article 36 of the Criminal Code (authorizing forfeiture of vehicles, vessels and aircraft) states that property is forfeitable if it is used “with the knowledge and consent of the owner” in the commission of a criminal offense,[61] the state’s burden is actually limited to proving that “such vessel or watercraft, vehicle, or aircraft was used in the commission of an offense described in Section 36-1.”[62] If the state proves that the property was used (by anyone, not necessarily by the owner) in the commission of an offense, then an innocent owner must “show by a preponderance of the evidence that he did not know, and did not have reason to know, that the vessel or watercraft, vehicle, or aircraft was to be used in the commission of such an offense” in order to avoid losing the property.[63]

Rules of Evidence

Both the Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act and the money laundering law provide that, “[d]uring the probable cause portion of the judicial in rem proceeding wherein the state presents its case-in-chief, the court must receive and consider, among other things, all relevant hearsay evidence and information. The laws of evidence relating to civil actions shall apply to all other portions of the judicial in rem proceeding.”[64] These provisions permit the government to introduce evidence that would otherwise be inadmissible as hearsay, while the property owner has no reciprocal right.

Awards of forfeited property to the seizing law enforcement agency

Several of Illinois’ forfeiture statutes explicitly authorize the Illinois State Police to award the seized property itself back to the law enforcement agency that seized it, or to the prosecutor, for “official use” after the property is declared forfeited.[65] Records received in response to a Freedom of Information Act request reveal that Illinois law enforcement agencies took advantage of these provisions: In 2014 and 2015 alone, hundreds of seized items, the vast majority of which were vehicles, were awarded to the seizing law enforcement agencies; electronics such as televisions, smartphones and tablets were also common items claimed by law enforcement for “official use.”[66]

Distribution of auction proceeds from forfeited property

Most of Illinois’ forfeiture laws provide that, when cash is forfeited or physical property is sold at auction, the proceeds are to be divided entirely among law enforcement agencies, in the following manner:

- 65 percent to the seizing agency;

- 12.5 percent to the prosecutor instituting the forfeiture action;

- 12.5 percent to the Office of the State’s Attorneys Appellate Prosecutor (the Office of the Cook County State’s Attorney, which handles its own appeals, receives 25 percent of forfeiture cases instituted in that county);

- 10 percent to the Illinois State Police

In some cases, the law requires a portion of the proceeds to be set aside for a special purpose. For instance, under Section 124B-305 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 50 percent of the proceeds of assets forfeited in connection with a prosecution for involuntary servitude, human trafficking or a related offense must be deposited into the Specialized Services for Survivors of Human Trafficking Fund.[67] The fund is administered by the Department of Human Services, and the monies set aside are required to be used for grants to organizations to provide services for victims of prostitution and human trafficking.[68]

Unlike other Illinois forfeiture statutes, Article 36 provides no fixed formula for dividing proceeds of property forfeited under that law. Rather, the statute provides that the entire proceeds of the forfeited property go to the same law enforcement agency that seized it, “after payment of all liens and deduction of the reasonable charges and expenses incurred by the State’s Attorney’s Office.”[69]

Reporting of seizures and forfeitures

Law enforcement agencies that seize property under the drug statutes,[70] the money laundering law,[71] and select provisions of Article 124B of the Code of Criminal Procedure[72] are required to report to the Illinois State Police certain basic information about the seized property. There is, however, no requirement that these data be made public or reported to state lawmakers and executive branch officials. Nor does the law require that the scant amount of information that is collected be aggregated or sorted in any particular form, nor that it be kept for any particular length of time. While a member of the public can access the information by issuing records requests to the State Police under the Freedom of Information Act, the available data paint an incomplete and somewhat confusing picture.

No reporting of seizures or forfeitures whatsoever is required under Article 36 of the Criminal Code, or under any of Illinois’ many other forfeiture laws. No data about these seizures or forfeitures are available through the State Police, with the exception of property seized by the department itself.

Furthermore, law enforcement agencies are not required under any law to report or account for their expenditures of monies received from distributions of forfeiture proceeds.

Illinois asset seizure and forfeiture data

Exactly how much private property has been taken from Illinois residents? And how much of this money was taken from people who’ve been proven guilty? Answers to these questions aren’t readily apparent because, even though the Illinois State Police keep track of asset seizures and forfeitures made throughout the state, their data don’t delineate whether or not a forfeiture was based upon an alleged crime for which the property owner or someone else was ultimately convicted.

The data below give a broad overview of both asset seizures and forfeitures that have taken place in Illinois. The data were provided in response to a Freedom of Information Act request to the Illinois State Police for state seizure and forfeiture information and the United States Department of Justice for federal seizures and forfeitures that have taken place in the state of Illinois.

These data have limits. For one, many seizures and forfeitures of property, such as those authorized under Article 36 of the Criminal Code, are not required to be reported by the seizing law enforcement agency to the State Police at all, and therefore are not included here. A second limitation of the Illinois State Police data is that they don’t clearly differentiate among seizures as to which were subject to civil as opposed to criminal forfeiture, and under which statute forfeiture was sought, so it’s difficult even to begin to distinguish when property may have been seized from an innocent owner. On the federal level, between 1997 and 2013, just 13 percent of forfeitures were criminal, while the overwhelming majority, 87 percent, were civil forfeitures.[73] So it may well be that the majority of the seizures in Illinois, too, are civil rather than criminal and, thus, lacked basic due process protections that usually accompany criminal proceedings. These data also do not tell how many of the seizures were contested by property owners, or how many were nonjudicial forfeitures.

The totals below describe the number of reported seizures – discrete interactions where law enforcement physically took private property under state or federal law – and the value of the property seized (values are exact for seized cash but estimated for vehicles and other forms of property). This report also includes data on forfeitures – assets that a court has adjudicated can be permanently kept by the government following seizure.

Because forfeitures that occurred during the relevant time period are inclusive of some property seized prior to that period, and because some of the property seized during 2005 – 2015 would not have been forfeited until sometime after the end of that period, the data don’t allow the tracking of cases from seizure to final disposition in order to determine, for instance, what percentage of property seized during 2005 – 2015 was ultimately forfeited. For this reason, the values of property seized and forfeited during these years will not be the same.

By Law Enforcement Agency

According to Illinois State Police data, the Chicago Police Department seized more reported assets than any other law enforcement agency in Illinois, followed by Illinois State Police themselves and the Chicago area-based Narcotics and Currency Interdiction Team:

Outside of task forces that operate throughout the state or in multiple jurisdictions, police departments in Decatur, Peoria, Rock Island and Joliet, along with sheriffs in Cook and Will counties, stand out for their high seizure numbers. This is somewhat unsurprising because they’re based in parts of the state with higher population numbers (largely Cook and collar counties) and higher crime rates.

By County/Jurisdiction

By far the largest amount of seizures take place in Cook County – again, this is unsurprising given its size and population relative to the rest of the state of Illinois.

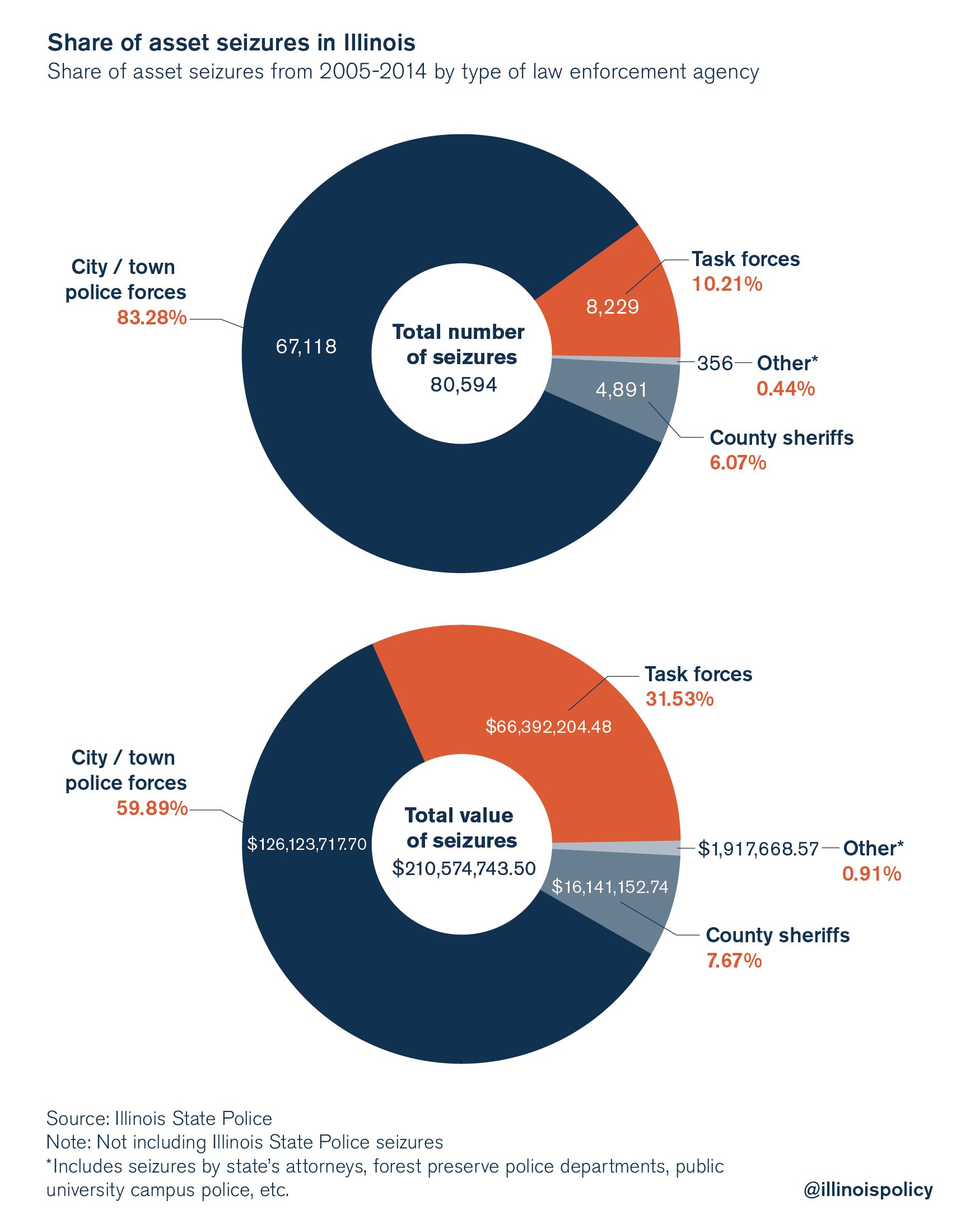

A mixture of law enforcement organizations, from state and city police departments, to county sheriffs, joint task forces, state’s attorneys and even public university police forces, conduct asset seizures in Illinois. The largest share come from city and town police forces, followed by task forces, county sheriffs, and a smaller group composed of state’s attorneys, park districts and other law enforcement groups.

A more specific method of comparison, however, looks at seizure rates by population in major Illinois cities. Rock Island, Decatur, Peoria, Chicago and Moline lead the state in the number of asset seizures per resident. Note that this calculation only includes seizures made by that city’s police agency, since it’s not possible to clearly pinpoint a task force seizure or a sheriff’s office seizure to a specific city when they have a wider geographic jurisdiction, usually at the county level.

A more specific method of comparison, however, looks at seizure rates by population in major Illinois cities. Rock Island, Decatur, Peoria, Chicago and Moline lead the state in the number of asset seizures per resident. Note that this calculation only includes seizures made by that city’s police agency, since it’s not possible to clearly pinpoint a task force seizure or a sheriff’s office seizure to a specific city when they have a wider geographic jurisdiction, usually at the county level.

In all, Illinois law enforcement seized over $278 million in assets between 2005 and 2015.

Illinois gained over $319 million from assets that were forfeited between 2005 and 2015.

Federal Seizure and Forfeiture Totals

As discussed earlier, both federal and state laws permit asset forfeiture. The following charts lay out the number and value of assets seized in Illinois under federal law either directly by federal agencies or through cooperation between federal and local law enforcement. These totals reflect the total value of assets seized and the total amount approved for federal forfeiture in the Illinois for Justice Assets Forfeiture Fund.

One major difference between federal and state seizures is that, on average, fewer assets of greater value are seized through federal seizures.

This report provides just a glimpse of the data acquired on asset seizures and forfeitures in the state of Illinois. For a much more detailed look, readers should see the Illinois Policy Institute’s online database of Illinois forfeiture data, which provides information regarding both the value and number of reported asset seizures made by every Illinois law enforcement agency from 2005 through 2015.

Reforms Illinois needs

Illinois forfeiture laws provide few protections for property owners, who have to pay for the right to challenge a seizure, and must then prove their innocence in order to keep their property, even if they were never convicted of, or even charged with, a crime. And nearly all of the proceeds from forfeiture go to law enforcement, creating a perverse incentive for law enforcement agencies to seek out opportunities to profit from forfeiture. In fact, Illinois ranks toward the bottom of a ranking of state asset forfeiture laws by the Institute for Justice, receiving a grade of D-minus for the quality of its protections for property owners.[74]

But reform is possible. Six states have enacted major reforms to their asset forfeiture laws so far in 2016 alone, including Virginia, California, Maryland, Florida, Michigan and Wyoming, along with New Mexico and Montana in 2015. States like Michigan have revamped the forfeiture reporting process to require law enforcement agencies to report seizures and forfeitures to the state police, who must then issue an annual report detailing them on its website. Michigan also raised the standard of proof for forfeiture proceedings to “clear and convincing evidence” before the government can take ownership of property in a forfeiture proceeding. The broadest reform, passed in New Mexico in 2015, ended civil asset forfeiture altogether. Today, no one in that state can have his or her property forfeited without first being convicted of a crime. These states and others have provided a roadmap for the kinds of reforms Illinois should consider as well.

There are at least 10 key points that Illinois lawmakers should consider to better protect the rights of innocent property owners:

- Require a criminal conviction before property can be forfeited to the government

No one should permanently lose his or her property to forfeiture without having first been convicted of a crime. One of the most basic yet substantive reforms Illinois could pass would be to require a criminal conviction as a prerequisite to civil asset forfeiture.

There can be no serious debate that having one’s property permanently confiscated constitutes a punishment. Civil asset forfeiture allows law enforcement to do an end-run around the criminal justice system while still imposing a severe punishment on the basis of a person’s alleged involvement in crime.

Justice is too easily compromised when, as in Illinois, quasi-criminal sanctions like civil asset forfeiture can exist completely unmoored from the criminal justice system and its attendant due process protections, like the defendant’s right to be represented by counsel and the government’s burden to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt. Requiring a criminal conviction as a prerequisite to the forfeiture of property in a civil proceeding would provide some measure of assurance that there has, in fact, been an actual crime to justify the imposition of this punishment.

- Place the burden of proof in forfeiture actions squarely upon the government

Basic norms of fairness mean property owners shouldn’t be burdened with proving their conduct was legal just to keep their property; rather, just as with a criminal charge, the state should have to prove wrongdoing before depriving Illinoisans of their liberty or property.

Right now, innocent owners who challenge forfeiture following seizure have to prove that they were not involved in the criminal activity alleged to have taken place, turning the principle that a person has the right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty – one of the cornerstones of the American legal tradition – on its head.

It is very difficult to even imagine how, in practical terms, a person might expect to succeed at proving a negative – that he or she was not involved in a crime, or did not know about or consent to a crime committed by another person. But that is precisely the predicament people in Illinois face when the state seizes their property and institutes civil forfeiture proceedings.

Lawmakers should correct this backward policy by relieving property owners of the burden to prove their innocence, and placing the burden of proof in forfeiture cases where it belongs: squarely upon the state.

- Raise the standard of proof for the government to prevail in a forfeiture case to clear and convincing evidence

There’s also a need to raise the standard of proof required to be met by the government in order to forfeit property in Illinois. The state’s current forfeiture laws employ low standards of proof: In a drug or money laundering case, the prosecutor need only show that there is probable cause to believe that property was involved in a crime in order to obtain an order of forfeiture. While this might be a fair standard for the seizure of property by police, a permanent order of forfeiture should require more. In Article 36 and other types of forfeiture cases, Illinois law employs the higher but still relatively low “preponderance of the evidence” standard, essentially that it’s more likely than not (at least 51 percent likely, in the judge’s view) that the property owner either used or gained the property illegally, instead of the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard required for criminal cases, or the intermediate “clear and convincing evidence” standard adopted by other states.

It is unclear what policy rationale, if any, justifies a lower standard of proof in some forfeiture cases than in others. Also unclear is the rationale for allowing the government, but not the property owner, to rely upon hearsay testimony that would ordinarily be excluded from evidence at trial.

Property rights are key to the exercise of basic liberties, not ancillary to them. Vehicles in particular are necessary to many Illinoisans’ ability to provide for themselves and their families; often one of the most expensive pieces of property people own, a car is a necessity for day-to-day life outside of the largest metropolitan areas. Because of the severe negative economic consequences that can flow from forfeiting a person’s property, the law should demand a reasonably high standard of evidence be brought to bear before forfeiture may be imposed. It is therefore appropriate that the standard of proof under Illinois forfeiture laws be raised to require clear and convincing evidence, and to level the playing field with regard to evidentiary rules.

- Eliminate nonjudicial forfeiture

All forfeitures of property should be approved and vetted by a judge in order to prevent the government from obtaining legal title to seized property before there has been a meaningful opportunity to ascertain and adjudicate the interests of the owner or owners.

Illinois took a modest step in the right direction in 2010 when the General Assembly passed a law requiring judicial review of seizures within 14 days in drug cases and Article 36 cases. However, the court’s inquiry in these hearings is limited to a determination of whether probable cause existed to seize the property; furthermore, the hearing is not required under the money laundering law or any of the other forfeiture statutes. Recent observation of the proceedings in Cook County’s forfeiture courtrooms suggests that a great many people still lose their property summarily in nonjudicial forfeitures, despite the 2010 reform.

A finding that probable cause existed for the seizure of property at the time it was seized should not by itself be dispositive of whether permanent forfeiture of the property to the government is justified. Even if the property owner does not appear in court after receiving notice, the prosecutor should be required to prove, through the presentation of evidence, allegations that the property in question was in fact used in or derived from criminal activity. Plaintiffs’ attorneys across Illinois are routinely required to go through a similar exercise in order to obtain default judgments against defendants who fail to appear for court in civil cases. There is no good reason not to hold prosecutors to the same standard.

- Require forfeiture proceedings to be instituted against the owner, rather than against the property itself

Illinois should dispense with the fiction that property can be guilty of a crime, and acknowledge the reality that forfeitures are punitive quasi-criminal sanctions against people. The General Assembly should adjust the legal procedural framework for forfeiture cases accordingly.

The law should require that before property can be forfeited, all owners should be identified by the seizing agency and/or the prosecutor bringing the forfeiture action, and that each owner be named in the caption of the forfeiture complaint and duly served with process like other defendants in civil actions. Illinois currently requires that “notice” be sent to a known owner’s address by certified mail but never requires confirmation that the person received the notice. The statutes should also be amended to require that the government’s pleadings set forth the specific legal and factual basis upon which it claims the authority to effect forfeiture of the property, in sufficient detail to put the person on notice of the action being taken against him or her. Particularly in light of the fact that the owner of seized property has no right to counsel in Illinois forfeiture proceedings, the law should at least ensure that he or she is afforded every opportunity to protect his or her own property rights.

- Eliminate direct financial incentives for law enforcement to seize and pursue forfeiture of property

Under Illinois law, the vast majority of forfeiture proceeds go to the budgets of the law enforcement agencies that initiate and litigate them. In most cases, 65 percent of forfeiture funds are kept by the seizing agency, 25 percent go to prosecutors, and 10 percent are given to Illinois State Police.

Thus, law enforcement members have contradictory incentives. They’re tasked with fairly and honestly enforcing the law; but the more seizures and forfeitures they engage in, justified or not, the more they pad their bottom line. With tens of millions in forfeiture dollars gained by Illinois police and prosecutors annually, and with relatively little transparency about how these funds are acquired or used, abuse is all but inevitable.

One solution to this problem is to send the proceeds for forfeitures to the general revenue fund of the state treasury rather than directly to law enforcement agencies. That way the state can preserve the purpose of forfeiture – discouraging crime by seizing its proceeds for public use – while avoiding direct financial incentives that encourage law enforcement to make seizures.

The General Assembly, which has the power of the purse under the Illinois Constitution,[75] should decide where public dollars are allocated, not law enforcement agencies. The state of Illinois may have other areas of need besides law enforcement that, if sufficiently funded, would have an equal or greater impact on crime reduction; for instance, forfeiture dollars could be spent on substance abuse treatment or economic development in poor communities. Furthermore, even if the General Assembly decides it is appropriate that law enforcement receive all proceeds from forfeiture, it does not follow that agencies should receive funding on the basis of how much property they themselves are able to seize for forfeiture.

Jurisdictions that have recently overhauled their forfeiture laws, such as New Mexico, Maryland, Maine and Washington, D.C. (starting in 2018), have enacted laws requiring that all forfeiture proceeds be directed to their general funds, in order to avoid incentivizing law enforcement to take private property. Illinois should follow suit and eliminate the current statutory framework under which law enforcement agencies and prosecutors have a direct financial stake in seizing and forfeiting people’s property.

- Require a link between forfeiture and a public safety benefit

Civil asset forfeiture is intended as a tool to reduce crime; therefore, as a matter of public policy, it should be authorized only where there is a logical link between forfeiture of the property and a beneficial public safety outcome.

Illinois law currently authorizes the forfeiture of property alleged to be an “instrumentality” of a drug offense – even if the predicate offense is the possession of a small quantity of a controlled substance for personal use. Reported case law confirms that Illinois courts have interpreted the law to authorize forfeiture of a person’s vehicle on the basis that an occupant possessed a small quantity of drugs in his or her pocket.[76]

While an argument could be made in support of forfeiting property involved in the sale or manufacture of illegal substances, it is unclear what public safety benefit the state of Illinois hopes to derive by forfeiting property from people whose only alleged crime is the possession of an illegal drug. It is likely that more than a few individuals whose property is seized on the basis of alleged drug possession may suffer from addiction or other substance use disorders, and may live in poverty. It is difficult to imagine how being permanently deprived of their cash, cars or other valuable property is supposed to make these individuals less likely to engage in criminal behavior.

The Illinois General Assembly should therefore amend the law to prohibit forfeiture on the basis of drug possession offenses that do not involve the manufacture of or intent to deliver drugs.

Furthermore, Illinois’ forfeiture statutes should be amended to explicitly allow the judge, before entering an order of forfeiture, to consider the severity of the alleged criminal conduct underlying the forfeiture case, the extent to which the property was involved in the crime, and the extent to which the owner is alleged to have participated in the crime. The judge should also be able to consider the value of the property to the owner, and whether the owner has already been punished for his alleged part in the crime as part of a sentence imposed in a criminal case. If the judge finds that forfeiture of the property would be grossly disproportionate to any culpability on the part of the property owner, then he or she should have the discretion to order the property returned to the owner. This change in the law would provide a disincentive for prosecutors to expend resources pursuing forfeiture cases when police have seized valuable property, such as a vehicle, on the basis of a relatively minor violation like small-time drug possession.

- Eliminate bond requirement to contest forfeiture

If an innocent property owner wants to challenge an unjust forfeiture, Illinois courts will charge him or her for that right. State law requires anyone contesting a seizure worth under $150,000 (if the case is brought under the Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act) or under $20,000 (in a money laundering case) to post a bond worth 10 percent of the value of their property or $100 – whichever is more – just for the right to have the case decided by a judge. This means an innocent party could have to pay up to $15,000 upfront, in addition to any legal fees, to contest the forfeiture. If the challenge fails, then the property owner loses the bond and must cover the legal costs of the prosecutor’s office. If the property owner wins, he or she still relinquishes 10 percent of the bond’s value in court fees, and still has his or her own legal costs to cover. The government that wrongly seized the property pays no cost.

Illinois is one of just five states that require forfeiture victims to pay courts for the right to challenge the forfeiture. The others are Hawaii, Michigan, Rhode Island and Tennessee.[77]

This is a significant barrier to justice. Not many people have thousands of dollars available for the bond, let alone enough to cover the cost of legal counsel. And the prospect of losing the bond and having to pay legal costs of the prosecution (along with his or her own legal costs) can easily persuade someone to forgo his or her property altogether.

Illinois should entirely eliminate the bond requirement, which serves no purpose other than to allow the state to intimidate forfeiture victims out of challenging unfair seizures.

- Improve reporting requirements

One of the most basic yet critical reforms Illinois can make would be to simply improve the way it collects asset seizure and forfeiture data and remove the barriers that keep the public from getting a full and accurate picture of this information.

The Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act outlines the requirement that law enforcement agencies report any seizures to their state’s attorney and the director of the Illinois Department of State Police, with the notable exception of seizures made under Article 36. This information is accessible to the public only through Freedom of Information Act requests. But it’s not terribly detailed – it does not show, for example, what portion of forfeitures followed criminal convictions or were only civil. It also doesn’t show exactly where and when each seizure took place, or provide information on the outcome of each seizure, such as if it was contested by the property owner or if it was eventually forfeited or not.

Furthermore, the data Illinois State Police do provide can be internally inconsistent. For example, the data provided in response to FOIA requests for asset seizure and forfeiture data between 2005 and 2015 would give vastly different totals when the exact same information was requested by county and then by specific law enforcement agency. In at least some cases, this supposedly happened because data were counted multiple times by the state’s forfeiture tracking system. This is why this report mainly relies on seizure data as reported from individual law enforcement agencies, rather than aggregations by county. Inaccuracy in reporting undermines transparency, preventing news organizations, researchers or even average concerned citizens from having reliable, accurate information from which to judge the utility and appropriateness of actions undertaken in their names.

What information should a more transparent tracking system provide? Some best practices in forfeiture reporting, suggested by the Institute for Justice, include:

- the date a seizure was made,

- type of property seized (including make, model and serial number for vehicles),

- what criminal offense was alleged to have taken place, the outcome of any criminal charges (which should be prerequisite for any seizure in the first place) and

- whether the forfeiture was criminal, civil or administrative; similarly detailed accounting needs to be made regarding how agencies spend the proceeds of forfeitures – whether for equipment, salaries or other expenditure permitted by law.

The more information the public has on the use and abuse of forfeiture funds, the better it can judge whether current practices live up to the assertion made in state law that forfeiture “is not intended to be an alternative means of funding the administration of criminal justice.”[78]

As of this publication, at least 14 states, including Michigan, Minnesota and New York, as well as the District of Columbia, require online reporting of asset forfeiture data. Illinois should follow suit by requiring state forfeiture data be posted online at least annually, in a report to the General Assembly.

- Strictly limit participation in federal equitable sharing program

One important but sometimes overlooked asset forfeiture reform on the state level is to also restrict state and local law enforcement agencies from engaging in equitable sharing programs with the federal government.

As detailed in this report, millions more dollars in property are seized in Illinois under federal law than under state law. The enormous sums forfeited under federal law in Illinois every year rank Illinois only 40th among states’ participation in equitable sharing programs with the Department of Justice.

But if Illinois joins the other states that have enacted reforms – such as requiring a criminal conviction as a prerequisite to forfeiture, raising the standard of proof to clear and convincing evidence, establishing greater protections for innocent owners, and ending improper financial incentives – then Illinois law enforcement agencies may be tempted to turn to federal law in order to sidestep those reforms and keep the forfeiture money flowing. Therefore, it is important that any legislation that reforms forfeiture procedures under Illinois law must also strictly limit Illinois law enforcement agencies’ participation in federal forfeitures.

Conclusion

The fact that tens of millions of dollars are taken by Illinois law enforcement every year, with few protections for the innocent and little transparency in how these funds are acquired or spent, does little to inspire trust in law enforcement in a time of widespread public distrust. For this reason among others, it is imperative that the General Assembly begin reforming the state’s asset forfeiture laws to ensure fairness, prevent abuse and promote transparency.

Mandating that law enforcement publicly report on how it acquires and uses forfeited funds would be a step forward, but it is not enough. Major substantive reforms are also required. Higher standards of evidence and removing financial bars to challenging forfeiture are key reforms that Illinois needs. And the government should never be able to permanently take away people’s property without a conviction or admission of guilt.

Property rights are too important to allow the government to routinely violate them with little oversight or accountability. Illinoisans should follow the lead of other states and demand the General Assembly put an end to asset forfeiture abuse.

Safety + Justice Challenge

This report was created with support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation as part of the Safety and Justice Challenge, which seeks to reduce over-incarceration by changing the way America thinks about and uses jails.

Endnotes

[1] According to a 2016 Cabrini-Green Legal Aid interview of a Cook County judge, the annual docket of cases heard in the forfeiture courtroom at the Richard J. Daley Center is approximately 2,000, and the ratio of cases is roughly one Article 36 case per two drug forfeiture cases; additionally, according to the website of the DuPage County State’s Attorney’s office, 394 Article 36 forfeiture cases were closed in 2008 in DuPage County alone, http://www.dupageco.org/States_Attorney/States_Attorney_News/2008/30380/.

[2] Dick Carpenter, Lisa Knepper, Angela Erikson, and Jennifer McDonald, “Policing for Profit: The Abuse of Civil Asset Forfeiture, Second Edition,” (Institute for Justice, November 2015).

[3] John G. Malcolm, “Civil Asset Forfeiture: Good Intentions Gone Awry and the Need for Reform,” (Heritage Foundation, 2015).

[4] For instance, a legislative declaration in Illinois’ own Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act states in relevant part: “The General Assembly further finds that the federal narcotics civil forfeiture statute upon which this Act is based has been very successful in deterring the use and distribution of controlled substances within this State and throughout the country.” (725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 150/2).

[5] U.S. Department of Justice website, https://www.justice.gov/afp.

[6] Austin Berg, “Police in Illinois Can Seize Your Property Without Convicting You of a Crime,” Illinois Policy Institute, June 9, 2016, https://www.illinoispolicy.org/police-in-illinois-can-seize-your-property-without-convicting-you-of-a-crime.

[7] Bryant Jackson-Green, “Illinois Policy Institute Poll: Robust Support for Criminal Justice Reform,” Illinois Policy Institute, August 2016, https://files.illinoispolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Criminal-Justice-Poll_Report_8.41.pdf.

[8] New Mexico Statutes § 31-27-6.

[9] Louisiana Statutes Ann. §§ 40:2602, 40:2611.

[10] Missouri Revised Statutes § 513.617.1.

[11] National Exchange Bank v. Wiley, 195 U.S. 257, 270 (1904); Iron Cliffs Co. v. Negaunee Iron Co., 197 U.S. 463, 471 (1905).

[12] Seitz v. Federal Nat. Mortg. Ass’n, 909 F. Supp. 2d 490 (E.D. Va. 2012).

[13] Becher v. Contoure Laboratories, 279 U.S. 388, 49 S. Ct. 356, 73 L. Ed. 752 (1929); R.M.S. Titanic, Inc. v. Haver, 171 F.3d 943 (4th Cir. 1999); Estate of Walton, 164 Ariz. 498, 794 P.2d 131 (1990); Dearing v. State ex rel. Com’rs of Land Office, 1991 OK 6, 808 P.2d 661 (Okla. 1991).

[14] Smith v. Hammel, 383 Ill. Dec. 459, 14 N.E.3d 742 (App. Ct. 5th Dist. 2014).

[15] 18 U.S. Code § 983.

[16] 8 U.S. Code § 983; 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 150/6.

[17] While Illinois law has since 2012 required a probable cause hearing prior to nonjudicial forfeiture of property, the rules of evidence are inapplicable at the probable cause hearing, 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 150/3.5(b); 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/36-1.5(b).

[18] Iowa Code § 809A.13(7); Texas Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 59.05(b); Maine Stat. tit. 15, § 5822(3); Mississippi Code Ann. § 41-29-179(2).

[19] North Dakota Cent. Code § 19-03.1-36.2; Massachusetts Gen. Laws ch. 94C, § 47(d); South Carolina Code Ann. §§ 44-53-520(b) to -586(b).

[20] Colorado Rev. Stat. §§ 16-13-307(1.7)(c) (public nuisance), 16-13-505(1.7)(c) (contraband), 16-13-509 (currency),18-17-106(11) (racketeering); Utah Code Ann. § 24-4-104(6); Florida Stat. § 932.704(8).

[21] Nebraska Rev. Stat. §§ 28-431(4), 28-1111; California Health & Safety Code § 11488.4(i); see also People v. $9,632.50 U.S. Currency, 75 Cal. Rptr. 2d 125, 128 n.4 (Ct. App. 1998).

[22] California Health and Safety Code § 11470(g) (requiring knowledge and consent of unlawful conduct by all residents in order to forfeit real property being used as a family residence or “for other lawful purposes”).

[23] Dick Carpenter, Lisa Knepper, Angela Erickson, and Jennifer McDonald, “Policing for Profit: The Abuse of Civil Asset Forfeiture, Second Edition,” (Institute for Justice, November 2015).

[24] New Hampshire Rev. Stat. Ann. § 318-B:17-b(V); South Dakota Codified Laws §§ 34-20B-64, 34-20B-89.

[25] D.C. Code § 41-310(a)(2); Maine Stat. tit. 15, §§ 5822(4), 5824; New Mexico Stat. Ann. § 31-27-7(B).

[26] North Carolina Const. art. IX, § 7; Mo. Const. art. IX, § 7; Mo. Rev. Stat. § 513.623 (provide that all forfeiture proceeds shall be used to fund schools).

[27] Virginia Code Ann. § 19.2-386.14(A1)–(B); Oregon Rev. Stat. §§ 131A.360(4), (6), .365(3), (5); New Jersey Stat. Ann. § 2C:64-6(a), (c).

[28] Arizona Rev. Stat. §§ 13-4315; 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 570/505(f).

[29] U.S. Department of Justice, Guide to Equitable Sharing for State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies, 2009, https://www.justice.gov/criminal-afmls/file/794696/download.

[30] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 570/505(a).

[31] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 646/85(a).

[32] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 550/12(a), 550/4(c).

[33] 410 Ill. Comp. Stat. 620/3.23(c).

[34] 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 150/1 et seq.

[35] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/36-1 et seq.

[36] See Appendix B (listing offenses for which Article 36 authorizes forfeiture).

[37] Forfeiture laws incorporating the procedural provisions of Article 36 include: the Illinois Streetgang Terrorism Omnibus Prevention Act (740 Ill. Comp. Stat. 147/1); Metropolitan Water Reclamation District Act (70 Ill. Comp. Stat. 2605/7(g)); and Counterfeit Trademark Act (765 Ill. Comp. Stat. 1040/9).

[38] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/29B-1 et seq.

[39] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/33G-6(b).

[40] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/17-10.6(m).

[41] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/33G-6(b).

[42] 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 175/5.

[43] 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/124B-5 et seq.

[44] See Appendix C (listing offenses for which forfeiture is authorized under Article 124B of the Code of Criminal Procedure).

[45] See Appendix A (listing Illinois statutes authorizing asset forfeiture).

[46] 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/ 124B-160.

[47] 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 175/5.

[48] 5 Ill. Comp. Stat. 283/10(a).

[49] 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 150/6(D); 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/29B-1(k)(4).

[50] 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 150/6.

[51] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/29B-1(k).

[52] Alvarez v. Smith, 130 S.Ct. 576 (2009); Adam W. Ghrist, “Drug asset forfeiture: Will the courts quiet the critics?” Illinois State Bar Association newsletter vol. 11, no. 4 (June 2010).

[53] Illinois Public Act 97-544 (effective January 1, 2012).

[54] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 29B-1(k)(3) & (4); 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 150/6(C) & (D).

[55] There are, however, exceptions: The Timber Buyers Licensing Act (225 Ill. Comp. Stat. 735/16) and the Forest Products Transportation Act (225 Ill. Comp. Stat. 740/14) each require the property owner or other person alleged to have illegally used or operated the seized property “to appear in court and show cause why the property seized should not be forfeited to the State.” (Emphasis added.)

[56] 5 Ill. Comp. Stat. 283/10(b); 305 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/8A-7(d)(1); 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/28-5(c); 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/36-2(d); 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/47-15(c); 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 175/5(b).

[57] 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 150/9(G).

[58] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/29B-1(l)(7).

[59] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/33G-6(b); 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/29B-1(l)(7).

[60] 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 150/8(A)(i).

[61] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/36-1(a).

[62] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/36-2(d).

[63] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/36-2(e).

[64] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/29B-1(l)(2); 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 150/9.

[65] 410 Ill. Comp. Stat. 620/3.23(f); 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 550/12(d); 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 570/505(d); 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 646/85(d).

[66] Information received from Illinois State Police pursuant to Freedom of Information Act 2015 request.

[67] 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/124B-305(b).

[68] 730 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/5-9-1.21.

[69] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/36-2(h).

[70] 410 Ill. Comp. Stat. 620/3.23(f); 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 550/12(d); 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 570/505(d); 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 646/85(d).

[71] 720 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/29B-1(h)(4).

[72] 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/124B-705; 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 5/124B-930.

[73] Dick Carpenter, Lisa Knepper, Angela Erickson, and Jennifer McDonald, “Policing for Profit: The Abuse of Civil Asset Forfeiture, Second Edition,” (Institute for Justice, November 2015).

[74] Ibid.

[75] Ill. Const. art. VIII, § 2(b) (1970).

[76] People ex rel. Mihm v. Miller, 89 Ill. App.3d 148 (1980).

[77] Hawaii, Haw. Rev. Stat. § 712A-10(9); Michigan, Mich. Comp. Laws § 333.7523(1)(c); Rhode Island, 21 R.I. Gen. Laws § 21-28-5.04.2(h)(4), (7); Tennessee, Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-33-206(b)(1).

[78] 725 Ill. Comp. Stat. 150/2.

image credit: RiverBender.com

Appendix A

Illinois statutes authorizing asset forfeiture (civil or criminal)

- Elected Officials Misconduct Forfeiture Act (5 ILCS 282/1 et seq.)

- Public Corruption Profit Forfeiture Act (5 ILCS 283/1 et seq.)

- Cigarette Tax Act (35 ILCS 130/3-10, 4f, 9c, 18, 24)

- Cigarette Use Tax Act (35 ILCS 135/3-10, 24, 30)

- Timber Buyers Licensing Act (225 ILCS 735/16)

- Forest Products Transportation Act (225 ILCS 740/14)

- Illinois Public Aid Code (305 ILCS 5/8A-7)

- Illinois Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (410 ILCS 620/3.23)

- Environmental Protection Act (415 ILCS 5/44.1)

- Herptiles-Herps Act (510 ILCS 68/105-55)

- Fish and Aquatic Life Code (515 ILCS 5/1-215)

- Wildlife Code (520 ILCS 5/1.25)

- Illinois Endangered Species Protection Act (520 ILCS 10/8)

- Criminal Code: Financial institution fraud (720 ILCS 5/17-10.6)

- Criminal Code: Gambling (720 ILCS 5/28-5)

- Criminal Code: Money laundering (720 ILCS 5/29B-1)

- Criminal Code: Illinois Streetgang and Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Law (720 ILCS 5/33G-6)

- Criminal Code: Article 36 Seizure and Forfeiture of Vessels, Vehicles and Aircraft (720 ILCS 5/36-1 et seq.)

- Criminal Code: Dumping garbage on real property (720 ILCS 5/47-15)

- Cannabis Control Act (720 ILCS 550/9; 720 ILCS 550/12)

- Illinois Controlled Substances Act (720 ILCS 570/405; 720 ILCS 570/405.2; 720 ILCS 570/505)

- Drug Paraphernalia Control Act (720 ILCS 600/5)

- Methamphetamine Control and Community Protection Act (720 ILCS 646/65; 720 ILCS 646/85)

- Article 124B of the Code of Criminal Procedure (Forfeiture) (725 ILCS 5/124B-5 et seq.)

- Drug Asset Forfeiture Procedure Act (725 ILCS 150/1 et seq.)

- Narcotics Profit Forfeiture Act (725 ILCS 175/5)

- Illinois Streetgang Terrorism Omnibus Prevention Act (740 ILCS 147/1 et seq.)

- Illinois Securities Law Of 1953 (815 ILCS 5/11)

Appendix B

Violations of Illinois law for which forfeiture is authorized under Article 36 (Vehicles, Vessels and Aircraft) of the Criminal Code of 2012

- First degree murder (720 ILCS 5/9-1)

- Reckless homicide/involuntary manslaughter (720 ILCS 5/9-3)

- Aggravated kidnapping (720 ILCS 5/10-2)

- Criminal sexual assault (720 ILCS 5/11-1.20)

- Aggravated criminal sexual assault (720 ILCS 5/11-1.30)

- Predatory criminal sexual assault of a child (720 ILCS 5/11-1.40)

- Indecent solicitation of a child (720 ILCS 5/11-6)

- Promoting juvenile prostitution (720 ILCS 5/11-14.4)

- Stalking (720 ILCS 5/12-7.3)

- Aggravated stalking (720 ILCS 5/12-7.4)

- Theft (720 ILCS 5/16-1) (if the theft was precious metal or scrap metal)

- Armed robbery (720 ILCS 5/18-2)

- Burglary (720 ILCS 5/19-1)

- Possession of burglary tools (720 ILCS 5/19-2)

- Residential burglary (720 ILCS 5/19-3)

- Arson (720 ILCS 5/20-1)

- Aggravated arson (720 ILCS 5/20-2)

- Aggravated discharge of a firearm (720 ILCS 5/24-1.2)

- Aggravated discharge of machine gun or firearm equipped with a silencer (720 ILCS 5/24-1.2-5)

- Reckless discharge of a firearm (720 ILCS 5/24-1.5)

- Gambling (720 ILCS 5/28-1)

- Possession of a deadly substance (terrorism) (720 ILCS 5/29D-15.2)

- Aggravated battery (720 ILCS 5/12-3.05(a)(1), (a)(2), (a)(4), (b)(1), (e)(1), (e)(2), (e)(3), (e)(4), (e)(5), (e)(6), or (e)(7))

- Violation of an order of protection (720 ILCS 5/12-4(a))

- Criminal sexual abuse (720 ILCS 5/11-1.50(a))

- Aggravated criminal sexual abuse (720 ILCS 5/11-1.60(a), (c), (d))

- Unlawful use of a weapon (720 ILCS 5/24-1(a)(6) or (a)(7))

- 35 ILCS 130/21, 22, 23, 24 or 26 of the Cigarette Tax Act if the vessel, vehicle or aircraft contains more than 10 cartons of such cigarettes

- 35 ILCS 130/28, 29 or 30 of the Cigarette Use Tax Act if the vessel, vehicle or aircraft contains more than 10 cartons of such cigarettes

- 415 ILCS 5/44 of the Environmental Protection Act

- Aggravated fleeing or attempting to elude a peace officer (625 ILCS 5/11-204.1)

- Driving under the influence (625 ILCS 5/11-501) when the defendant’s driving privileges are revoked or suspended for a DUI, for a violation of leaving the scene of an accident involving personal injury or death under 625 ILCS 5/11-401, or for reckless homicide under 720 ILCS 5/9-3

- DUI, 625 ILCS 5/11-501, where the accused has a previous conviction for reckless homicide involving alcohol or drugs, or a previous conviction for DUI where the violation caused an accident that resulted in death, great bodily harm, or permanent disability or disfigurement to another, when the violation was a proximate cause of the death or injuries

- Aggravated DUI, 625 ILCS 5/11-501, where the accused has two prior offenses

- DUI, 625 ILCS 5/11-501, where the accused did not have a driver’s license

- DUI, 625 ILCS 5/11-501, without insurance

- Driving while license suspended or revoked, 625 ILCS 5/6-303(g), where the suspension/revocation is for a DUI, reckless homicide, or leaving the scene of an accident involving injury or death

- Driving without a valid license, 625 ILCS 5/6-101(e), where the person also did not have insurance and caused an accident resulting in injury or death

Appendix C

Violations of Illinois law for which forfeiture is authorized under Article 124B of the Illinois Code of Criminal Procedure

- Involuntary servitude; involuntary servitude of a minor; or trafficking in persons (720 ILCS 5/10-9, 10A-10)

- Promoting juvenile prostitution (720 ILCS 5/11-14.4) or keeping a place of juvenile prostitution (720 ILCS 5/11-17.1, Criminal Code of 1961) or exploitation of a child (720 ILCS 5/11-19.2, Criminal Code of 1961)

- Second or subsequent act of obscenity (720 ILCS 5/11-20)

- Child pornography (720 ILCS 5/11-20.1) or aggravated child pornography (720 ILCS 5/11-20.1B, 11-20.3, Criminal Code of 1961)

- Nonconsensual dissemination of private sexual images (720 ILCS 5/11-23.5)

- Unlawful transfer of a telecommunications device to a minor (720 ILCS 5/12C-65), (720 ILCS 5/44, Criminal Code of 1961)

- Computer fraud (720 ILCS 5/17-50, 16D-5)

- Felony WIC fraud (720 ILCS 5/17-6.3, 17B)

- Felony dog fighting (720 ILCS 5/48-1), (720 ILCS 5/26-5, Criminal Code of 1961)