Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot Sept. 20 proposed a $16.7 billion budget that includes a $76.5 million property tax hike, which – after accounting for revenue from new property – would raise property tax bills by an average of $72 to $180, depending on a homeowner’s region of the city. The tax increase is modest compared to the $543 million increase under Mayor Rahm Emanuel in 2015, and less than the $94 million property tax hike in Lightfoot’s budget last year. Still, it would add an unnecessary burden to a city economy still recovering from COVID-19 and was unnecessary given the city is sitting on $3.5 billion in federal aid.

The budget increases spending by roughly $1.2 billion on a range of city services from the Chicago Police Department, affordable housing, and mental health services to a pilot program for a universal basic income. Unfortunately, that spending is propped up by one-time federal aid that expires by 2024 – meaning many programs will have to be cut or financed with significant tax hikes within just two years.

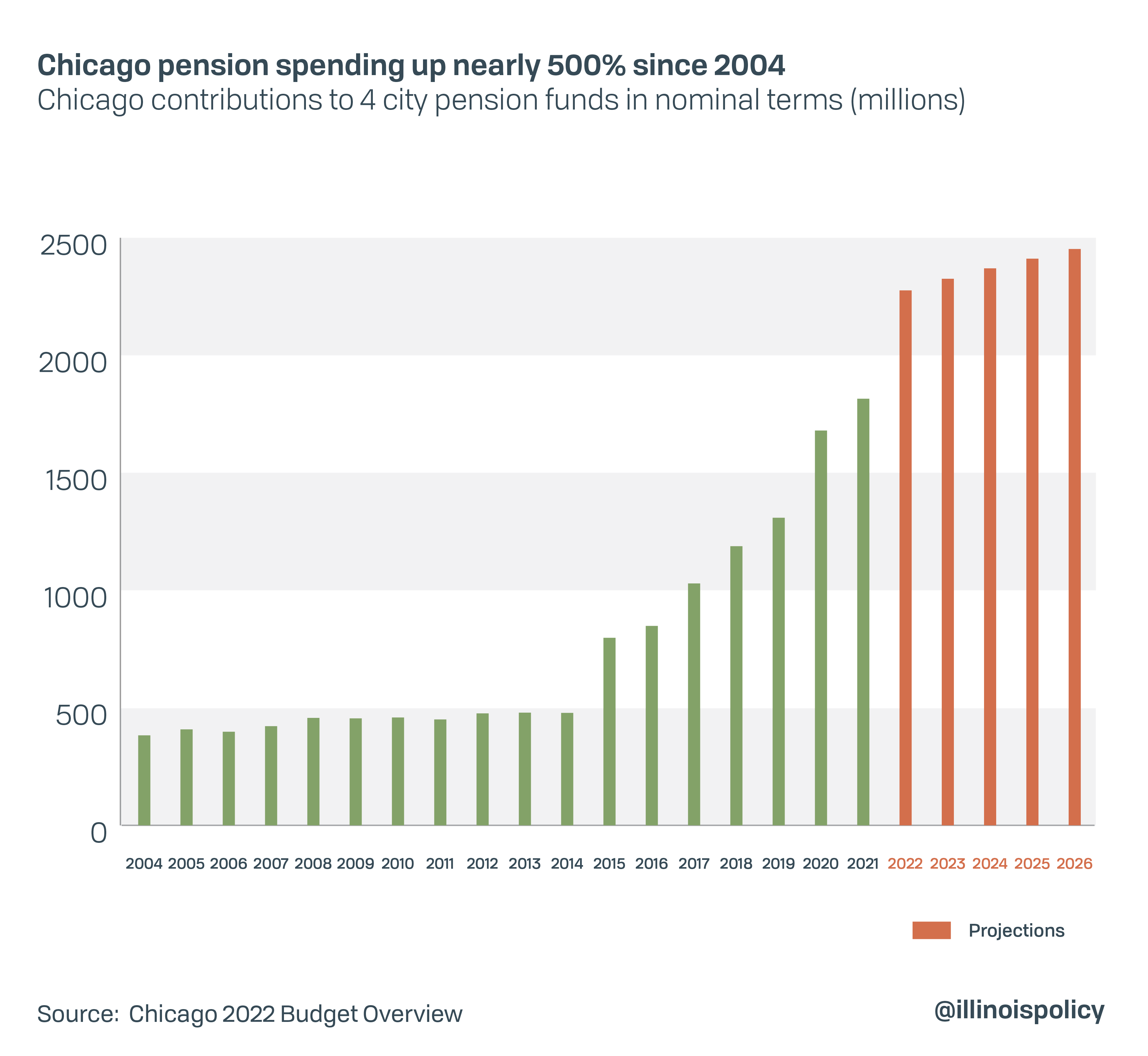

Pension costs will consume more than $2.3 billion of the city’s budget, or 21.4 percent of its own source revenue, excluding state and federal grants. That’s more than a $967 million increase in pension spending since Lightfoot became mayor and $461 million more than last year, a spike that accounts for 63 percent of the $733 million 2022 budget deficit reported by Lightfoot in August.

Lightfoot’s speech did not include any call for pension reform, which requires Springfield to send a constitutional amendment to voters. This comes despite her statements in May that the pension crisis was the city’s “biggest problem” and “unsustainable in its current form.”

Below is a detailed breakdown of Lightfoot’s 2022 budget proposal, and three reasons it fails to solve the city’s long-term problems of runaway pension debt, inadequate public service quality, and out of control tax burdens.

Lightfoot’s $76 million property tax is avoidable, will undermine economic recovery

In her budget address, Lightfoot emphasized that her budget proposal achieves balance “without any new taxes, no reduction in city services, and no layoffs.” Similarly, a press release from the mayor’s office claims the budget has “no new tax or significant fee increases for our residents.”

However, the budget includes a $76.5 million property tax increase that raises total property tax collections to $1.71 billion. That increase comprises $22.9 million in automatic increases after Lightfoot pushed for tying property taxes to inflation last year, $25 million for debt service on bonds for Lightfoot’s $3.7 billion infrastructure plan, and $28.6 million from new property.

Even after deducting the new property growth, the $47.9 million discretionary property tax hike would result in a roughly $180 increase in property tax bills for residents in Chicago’s central region, a $156 tax bill increase for Northern region homeowners, and $72 in the city’s southern region. That estimate assumes 2022 assessments allocate property tax burdens proportionally with 2021, but individual bills may vary due to ongoing changes to Cook County assessments as well as changes in individual property value.

Lightfoot claims this doesn’t count as a tax increase because the automatic inflation increases and the increase for infrastructure were approved last year, but this argument is political spin – the bottom line is that city property owners will pay higher property taxes next year.

“There is a property tax increase. And many of our colleagues’ communities have received significant property tax increases in recent months. My community is about to get one,” Ald. Matt O’Shea told the Chicago Sun Times.

Similarly, the Chicagoland Chamber of Commerce said in response: “The current proposal calls for the second consecutive increase in the property tax levy in two years, all at a time when businesses are seeing their property tax assessments skyrocket without any clear reason why. In addition, many businesses within the hospitality industry including hotels, restaurants and bars are still struggling and need direct support.”

Illinois’ pandemic restrictions, as well as $655 million in state tax hikes pushed in Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s budget this year, have together contributed to the struggle for Illinois’ businesses to create jobs for workers as fast as the rest of the nation. The state’s unemployment rate remains 35 percent higher than the national average. Piling on even modest additional tax hikes on Chicago residents and businesses will mean fewer jobs and lower wage growth for residents as the economy recovers from the COVID-19 recession.

“With the historic level of federal funding coming to the city,” the Chicagoland Chamber of Commerce went on to say, “we can avoid a property tax increase that impacts all residents and businesses.”

The business community is right that this property tax increase is unnecessary in light of the $3.5 billion in pandemic related federal aid the city has received, including $1.9 billion in flexible funds from the American Rescue Plan Act. The budget uses $782 million of federal funds to replace 2021 revenues, $385 million for 2022, and reserves $152.4 for 2023 revenue replacement. That leaves roughly $581 million in flexible aid currently dedicated to new program spending, only a small portion of which would be necessary to prevent the property tax hike.

Moreover, U.S. Treasury rules’ prohibition on using federal aid for tax cuts only applies to states, not cities. That means Lightfoot could go even further and use the aid to undo last year’s property tax increase, which hit in the midst of a pandemic and related economic downturn. This meets the American Rescue Plan’s goal to “support immediate economic stabilization for households and businesses.”

Spending on new and existing programs at risk due to reliance on federal aid, debt-swap schemes

Lightfoot is proposing a total of $1.2 billion in new spending on social services she calls “community priorities,” including:

- $635 million on affordable housing programs

- $202 million to combat homelessness

- $170 million on anti-violence programs

- $150 million on youth employment and job training

- $86 million on mental health services

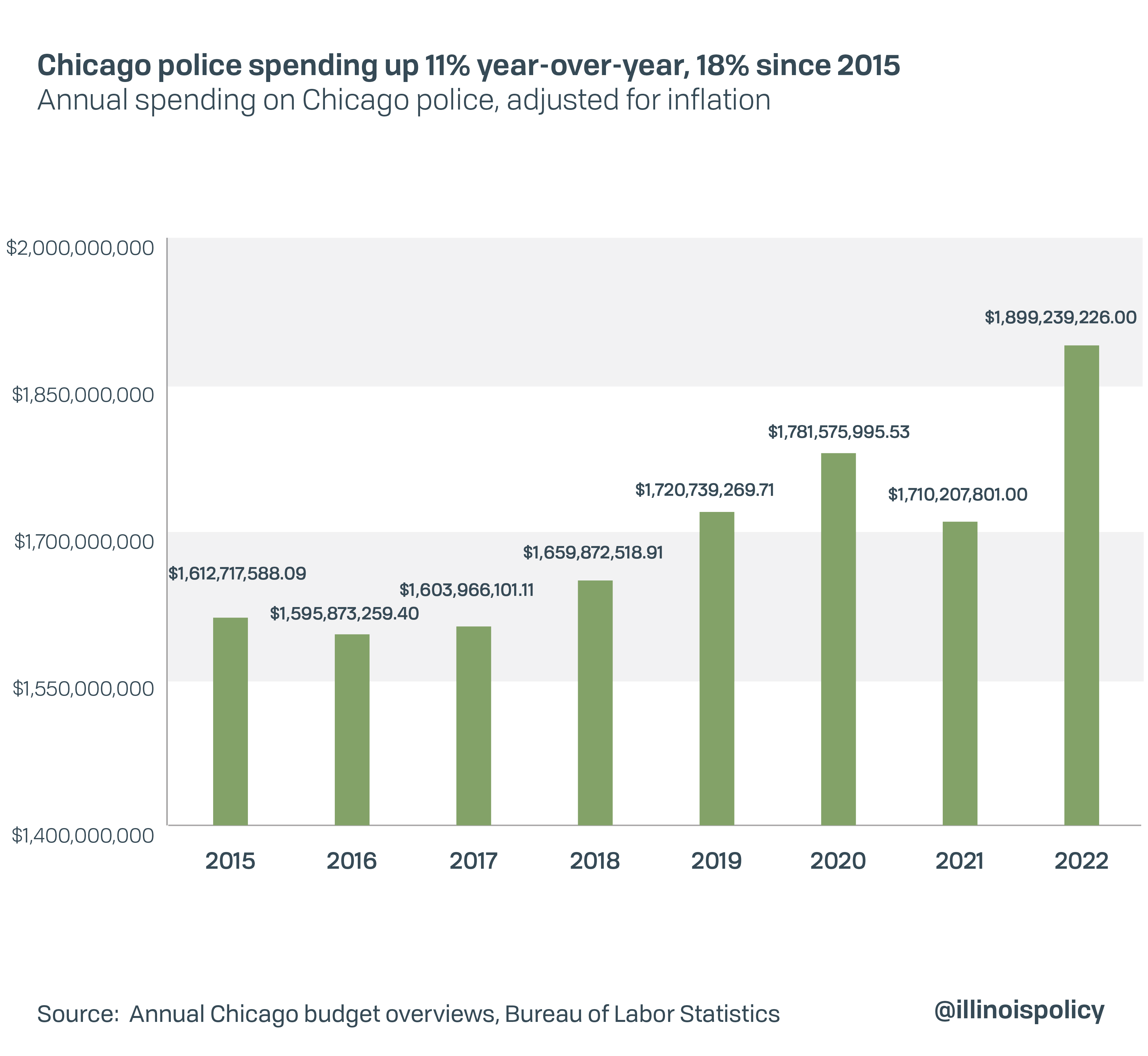

The budget also includes $32 million for the creation of a universal basic income pilot program, which will send $500 in monthly cash assistance to 5,000 families. And it spends $189 million more for Chicago police, with roughly 75% or $142 million going to pay raises in the new union contract.

That increase in police spending will bring the department back to baseline and then some, after inflation-adjusted police spending fell in 2021.

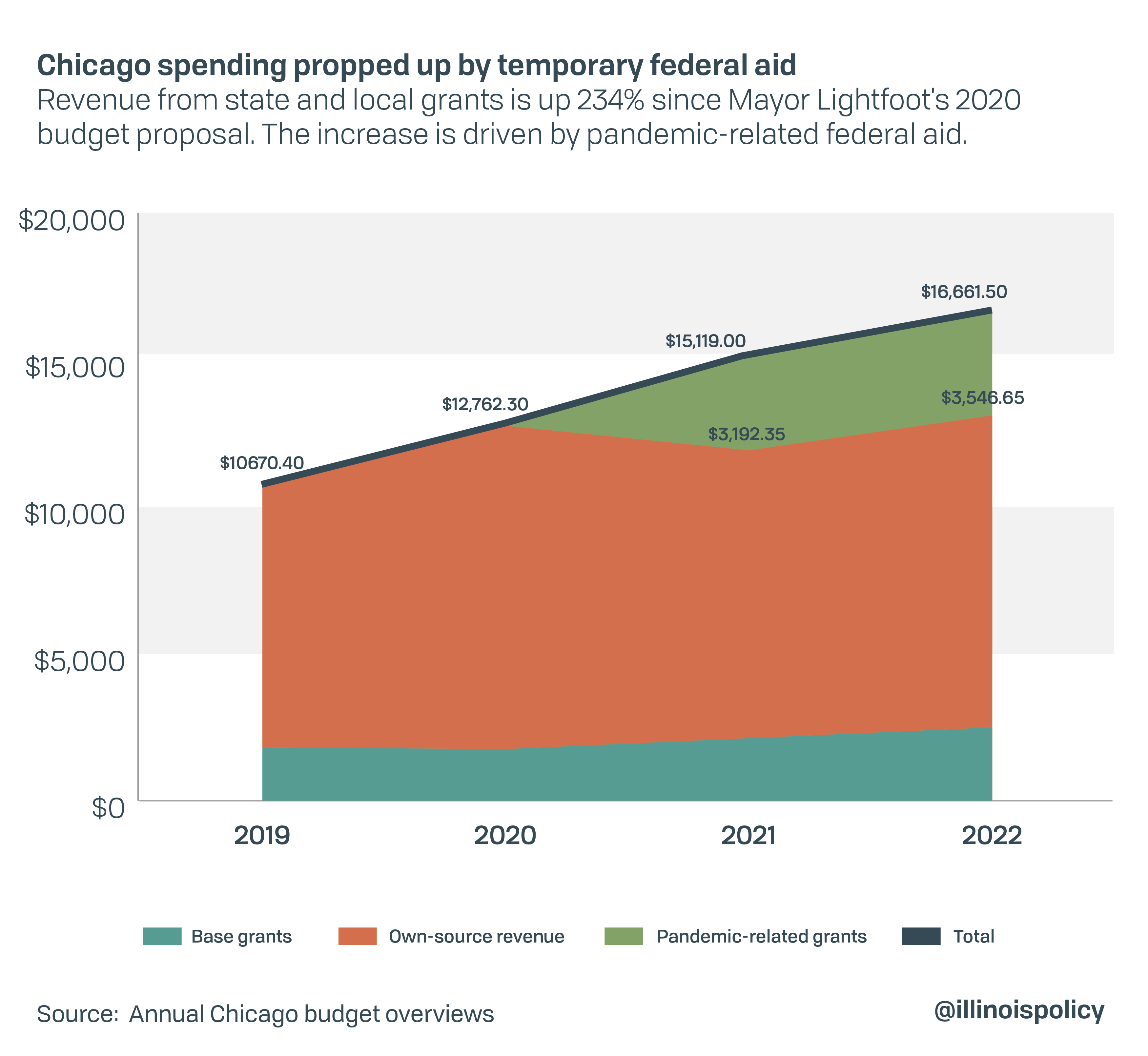

Many of these investments are needed and would help Chicagoans recover from the negative impacts of the pandemic and related recession. However, the budget’s reliance on one-time revenue sources means much of the funding for these programs will either run out or need to be covered with significant future tax increases.

While Chicago received $1.9 billion in general budgetary aid from the recent American Rescue Plan Act, its total available federal funding for the 2022 budget equals $3.5 billion. According to city budget documents, this includes a total of $2.6 billion from the American Rescue Plan, $447.8 million from the CARES Act, $366.1 million from a December 2020 supplemental funding package, and $168.8 million in federal emergency management assistance.

This flood of federal funds has grown Chicago’s budget 56 percent since 2019, despite modest local-source revenue losses during the pandemic.

When these funds run out, Chicago will be forced to reduce or eliminate programs or impose further tax increases to maintain them. CARES Act funds expire at the end of 2021 and American Rescue Plan funds must be used for expenses incurred by the end of 2024.

Additionally, the budget continues Chicago’s long history of using debt-swap schemes to pay for operations in three ways. First, it relies on the sale of $660 million in new general bond debt to fund Lightfoot’s community investments, on top of federal aid. Second, it refinances $1.2 billion of existing borrowing and front loads the savings, relying on $232 million to pay retroactive raises in the new police contract. Third, it indirectly uses federal funds to repay $450 million in borrowing used for the 2021 Chicago budget.

While U.S. Treasury rules prevent federal aid from directly repaying debt, they do nothing to prevent state and local governments from simply paying off debt with local revenues and replacing those revenues with federal dollars. “The city can’t directly pay off the credit line with ARP monies but it can direct them to make up for lost revenues freeing up other corporate fund dollars to pay off the credit line,” Bond Buyer explains.

The state of Illinois relied on a similar shell game to repay borrowing issued during the pandemic.

In some cases, these financial maneuvers can be fiscally prudent in the short term, resulting in interest savings for taxpayers. However, in the long run, reliance on temporary revenues and debt refinancing schemes undermines the stability of Chicago government services and places taxpayers at risk of future tax hikes.

Pension reform is the only way to deliver quality services with reasonable taxes

While in the past, Lightfoot has been refreshingly forthright about the severity of Chicago’s pension crisis, she has always stopped short of pushing for a realistic solution.

A case in point: In 2019 the mayor criticized 3 percent compounding post-retirement benefit increases for pensioners as “unsustainable.” She further said that switching to a true cost-of-living adjustment, meaning the increases are tied to inflation, is “something that we absolutely have to talk about.”

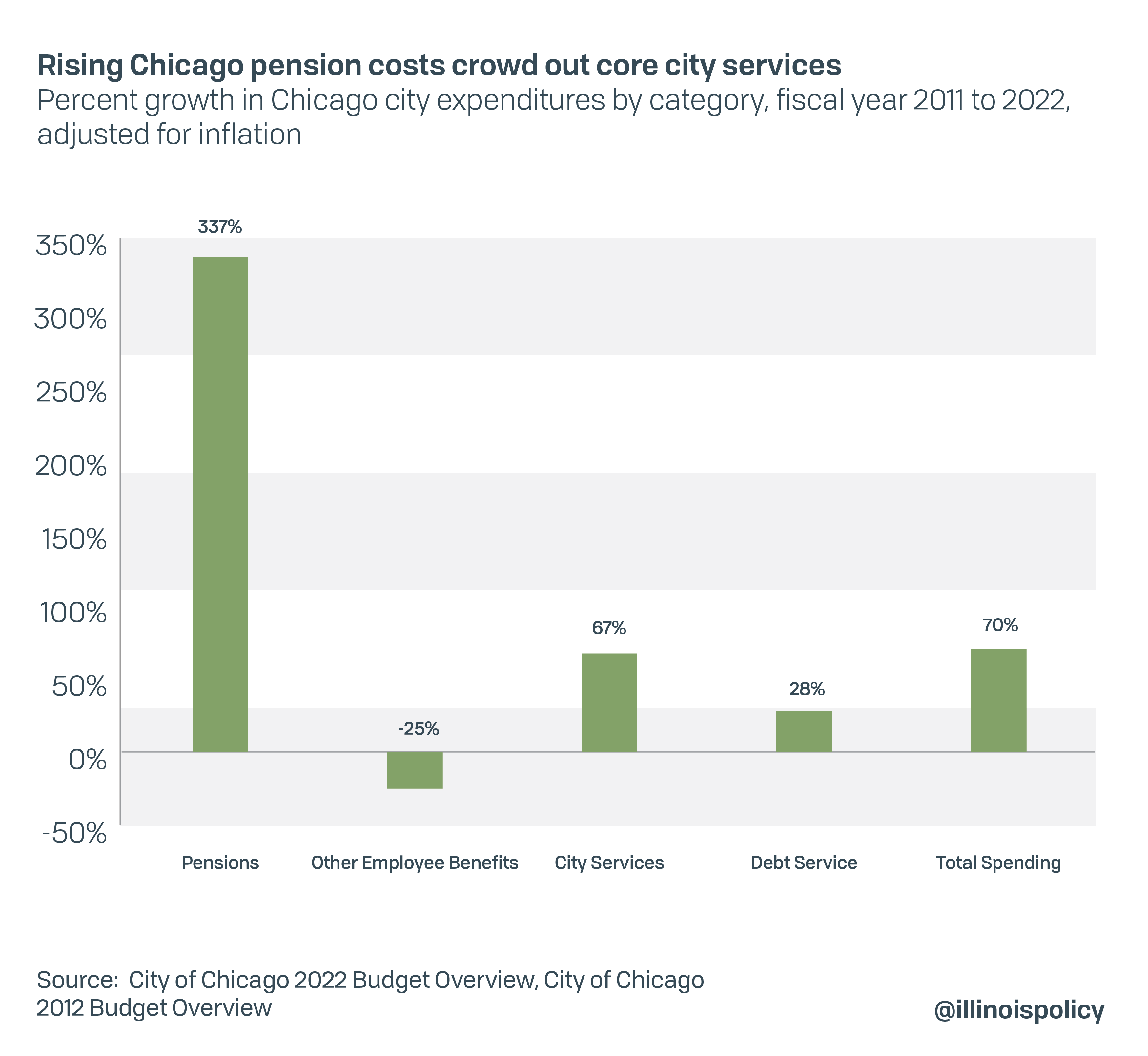

She’s right. Chicago recently ranked 141st out of 150 cities for municipal service quality. The primary reason for Chicago’s poor city services despite its high tax burdens is that most of the money is eaten up by the pension crisis. From 2011 to 2021, spending on pensions has increased 239 percent, while spending for city services has only increased 18 percent. If the final 2022 budget looks like the mayor’s proposal, the increase in pension spending since 2011 will reach 337 percent while service spending will appear to have grown 67 percent.

However, as previously noted, much of the mayor’s new spending cannot be continued when federal aid expires. Reforming pensions as the mayor alluded to in 2019 would free up additional resources for service spending.

Yet the mayor has refused to say she supports an amendment to the state constitution’s pension clause – which currently says even the future growth of pension benefits cannot be “diminished or impaired” – much less actually push for that solution in Springfield. Amending the constitution to allow for adjustments to the future growth in pension benefits for current workers and retirees is the only way for Lightfoot or the many other mayors around the state who are struggling with pensions to get their budgets and tax burdens under control.

Without an amendment, the COLA reforms Lightfoot said we ought to be talking about are a non-starter.

In a column for Crain’s Chicago Business, Joe Cahill pointed out the inconsistency between Lightfoot’s statements and actions. “You would think a public official who sees the cause of a problem so clearly would support action to address it,” Cahill wrote. Instead, Lightfoot told the Crain’s editorial board that she does not currently support a pension amendment, demonstrating the same failure of “political will” she blames for state politicians’ inaction.

The mayor mentioned pensions only once in her 2022 budget speech, noting that this is the first year the city will make actuarially determined pension payments. “This is huge,” the mayor said.

Certainly, the costs for taxpayers are huge. Actuarially determined payments mean that the annual pension contributions for all four pension funds the city pays into will be based on a formula of what it would take to pay down the debt. Previously, Mayor Rahm Emanuel lobbied for legislation that wrote specific pension contribution dollar amounts into state law. Those amounts were largely arbitrary and artificially low, creating a backloading effect similar to the state’s infamous “Edgar Ramp.”

Chicago’s pension spending is up nearly $1 billion just during the three years Mayor Lightfoot has been in office and nearly 500 percent since 2004 in nominal terms.

Yet still, the city is not paying in what it would take to stop the debt from growing, as “actuarially determined” is not the same thing as “actuarially sufficient.” Both the state of Illinois and the city of Chicago chronically underfund their full required payments by targeting 90 percent funding instead of 100 percent, along with relying on other unrealistic accounting assumptions.

In other words, Chicago’s rapid and unsustainable growth in pension spending still won’t be enough without benefit reforms.

If Lightfoot wants to live up to the rhetoric in her budget address – in which she promised to invest in Chicago’s economic recovery while giving predictability and stability to taxpayers – she needs to develop and execute a plan to match revenues and expenses long-term. Only a long-term balanced budget can give city residents confidence programs will continue and taxes will remain affordable.

Springfield must let the people vote on a constitutional amendment to control rising pension costs. Lightfoot needs to use her platform as a public official to push the General Assembly into doing the right thing if Chicago is going to reverse its economic stagnation and provide residents with quality services at a reasonable cost.