Pritzker claims statewide economic growth, but these Illinois metro areas are shedding jobs

Despite Gov. J.B. Pritzker touting growth in “every major region,” Illinois shed jobs in three metropolitan areas and lagged the national average in seven more.

In his Jan. 29 State of the State address, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker proclaimed, “Last year, for the first time in nearly 20 years, every major region in our state was growing simultaneously.”

But government data shows something else: metro areas throughout the state are seeing fewer jobs and smaller workforces.

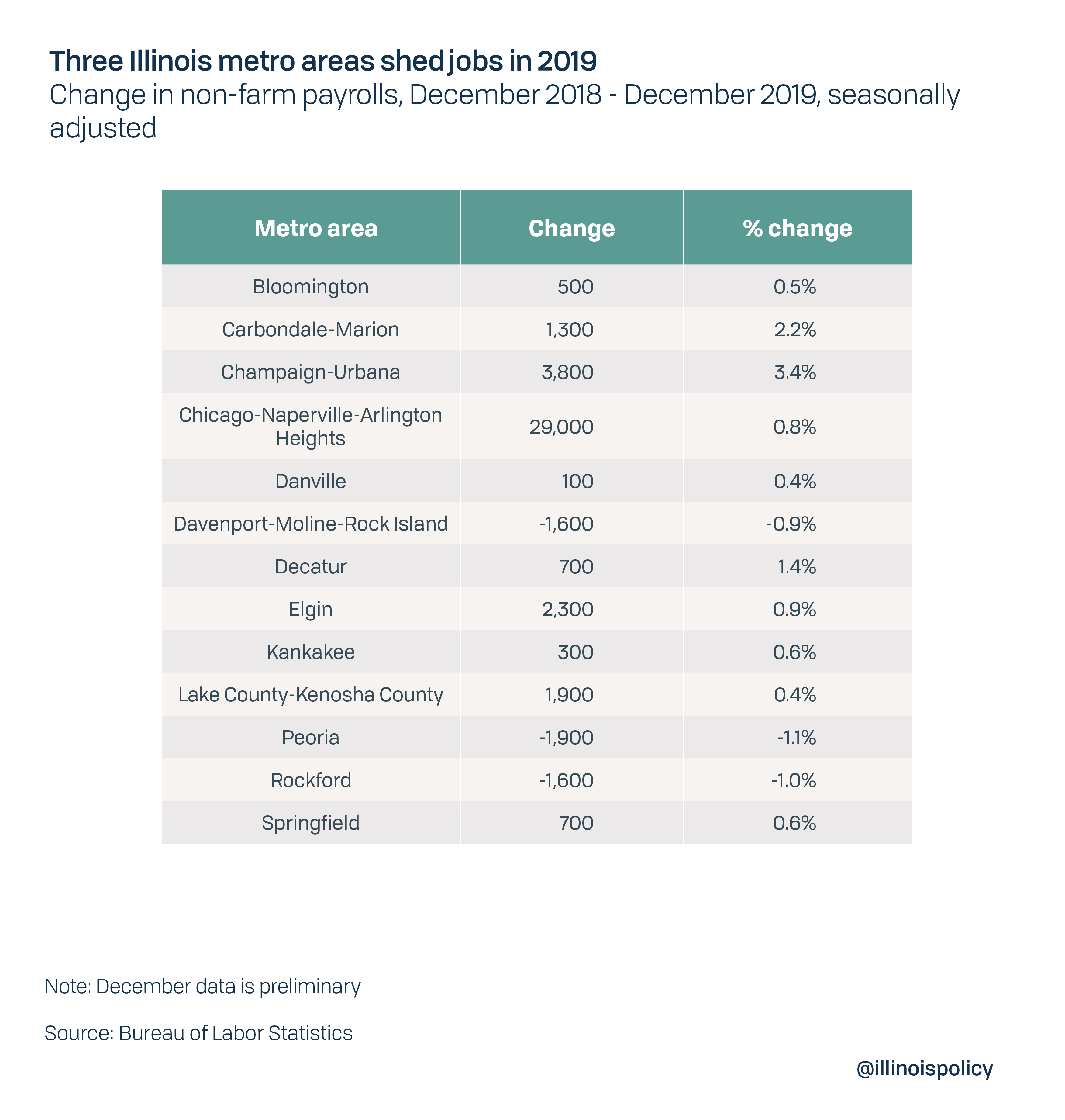

Illinois’ sluggish jobs growth in 2019 actually resulted in several metropolitan areas shedding jobs during the year. Nearly all Illinois metro areas lagged the national average for job creation, according to preliminary data from the Illinois Department of Employment Security and Bureau of Labor Statistics.

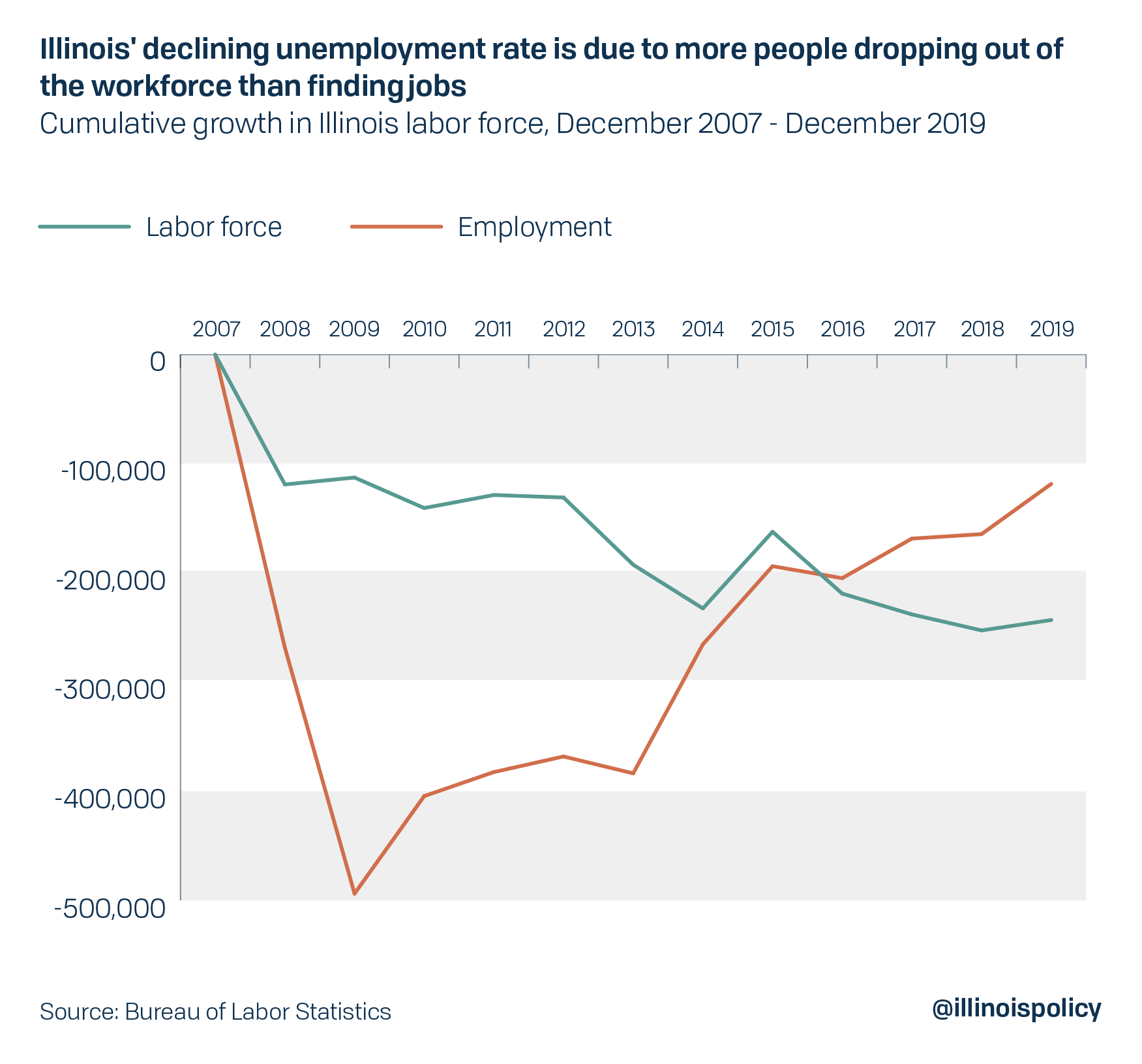

The federal data reveals concerning information about why Illinois’ unemployment rate is declining: It’s not because more people are working.

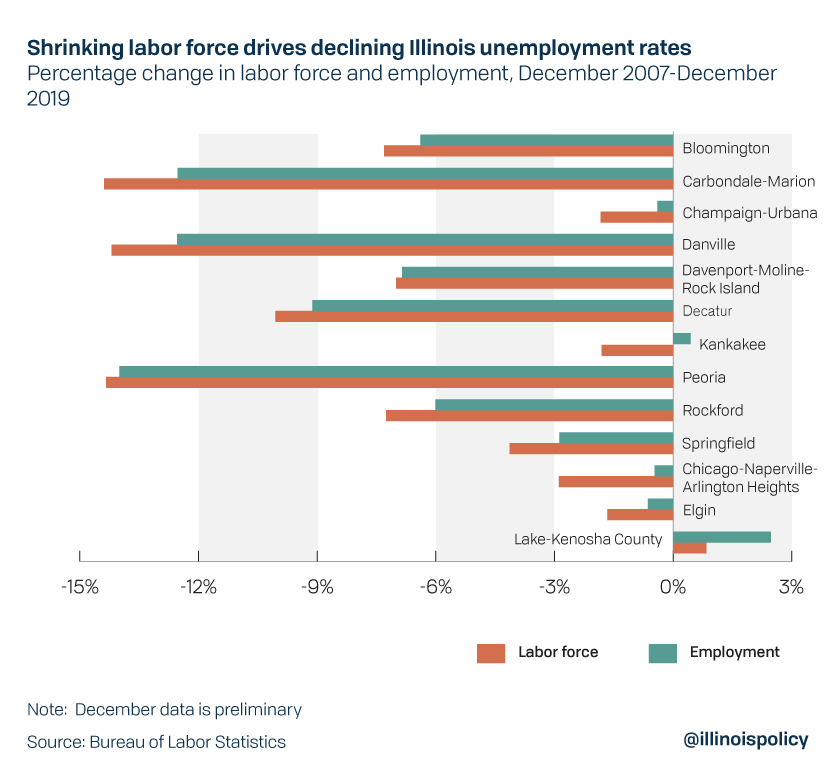

Illinois’ record-low unemployment rate has been driven entirely by Illinoisans exiting the workforce. Relative to pre-recession peaks, fewer people are employed now than in the past, which means Illinois’ unemployment rate has only fallen because more people are giving up on working. The rest of the nation achieved record-low unemployment rates through strong employment growth.

Local jobs data contradicts Pritzker’s claim

The governor’s mention of growth across Illinois doesn’t reflect recently released Census Bureau numbers, which confirmed Illinois’ population declined for the sixth consecutive year in 2019. And while data has yet to be released showing which areas of Illinois fared the worst, data from 2018 revealed population loss had actually spread to every metropolitan area for the first time in state history.

The governor’s growth claim also fails to hold up if he was referring to jobs numbers.

During the past year, three Illinois metro areas – Peoria, Rockford and Davenport-Moline-Rock Island – experienced a decline in the number of non-farm payroll jobs. In fact, the Peoria and Davenport-Moline-Rock Island areas’ performances were among the worst in the nation.

Of the metro areas that experienced jobs growth during the year, only two – Carbondale-Marion (+2.2%) and Champaign-Urbana (+3.4%) – outperformed the national average of 1.4% growth. Decatur’s performance matched the rest of the nation. Meanwhile, Illinois’ 10 other metropolitan areas lagged the national average.

St. Clair, Madison and other Metro East counties are included in the St. Louis metropolitan area, which added 14,300 jobs (+1.0%) from December 2018-2019, however IDES doesn’t report on jobs growth for the area because it is predominantly Missouri data. Unemployment data from the Illinois portion of the St. Louis metro area shows a 3.7% unemployment rate, indicating similar labor market outcomes as the rest of the state.

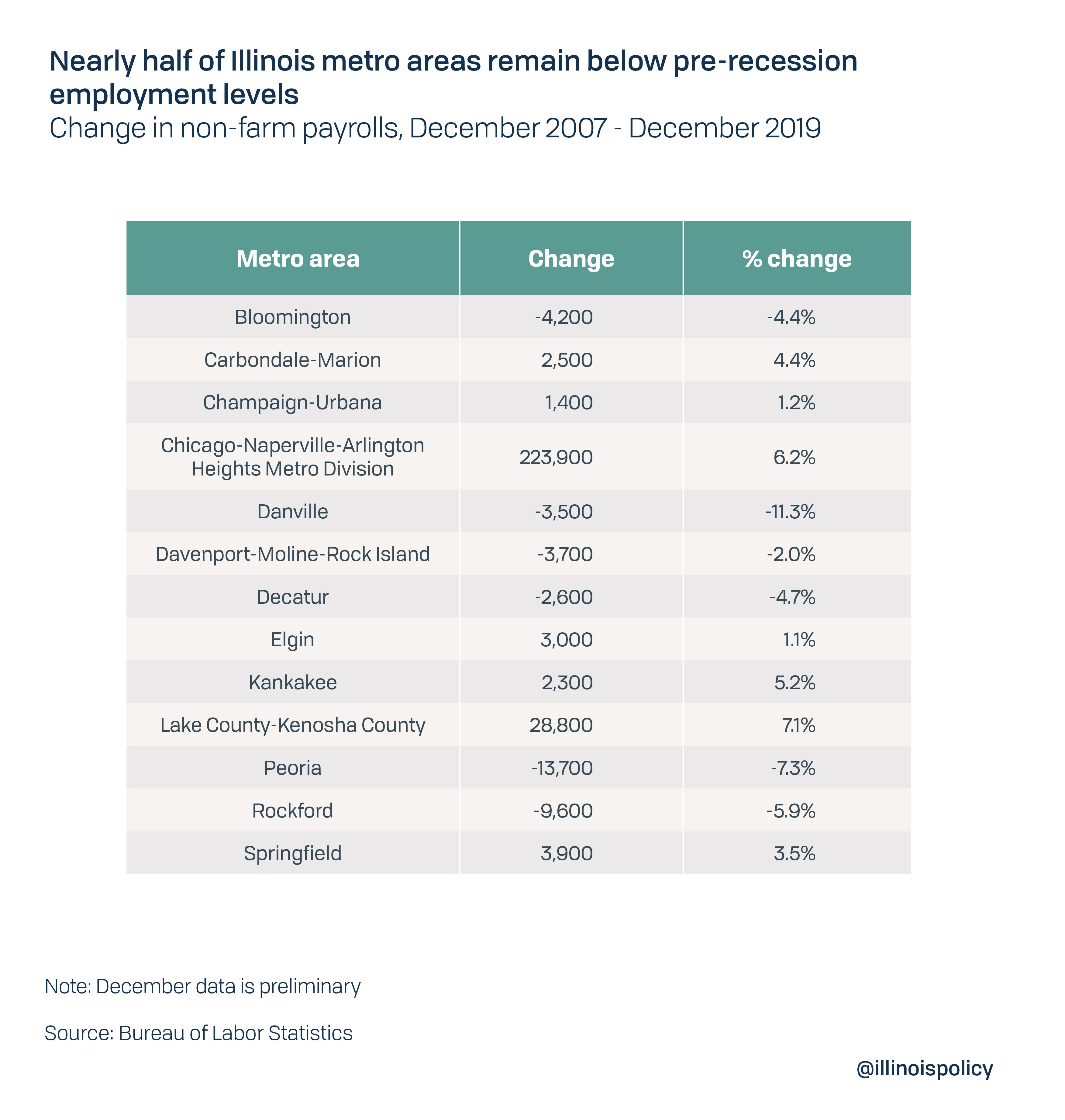

The historical context of Illinois’ 2019 payroll figures makes matters worse. Six of Illinois’ 13 metropolitan areas have non-farm payrolls that remain below their pre-recession levels.

While jobs in nearly half of Illinois’ metropolitan areas have declined since the recession, all Illinois metro areas have lagged the national average in jobs growth since 2007. The rest of the nation has grown jobs by 10.1% on average since December 2007, but even Illinois’ strongest performing areas severely lag the rest of the country.

Unemployment rates still stubbornly high

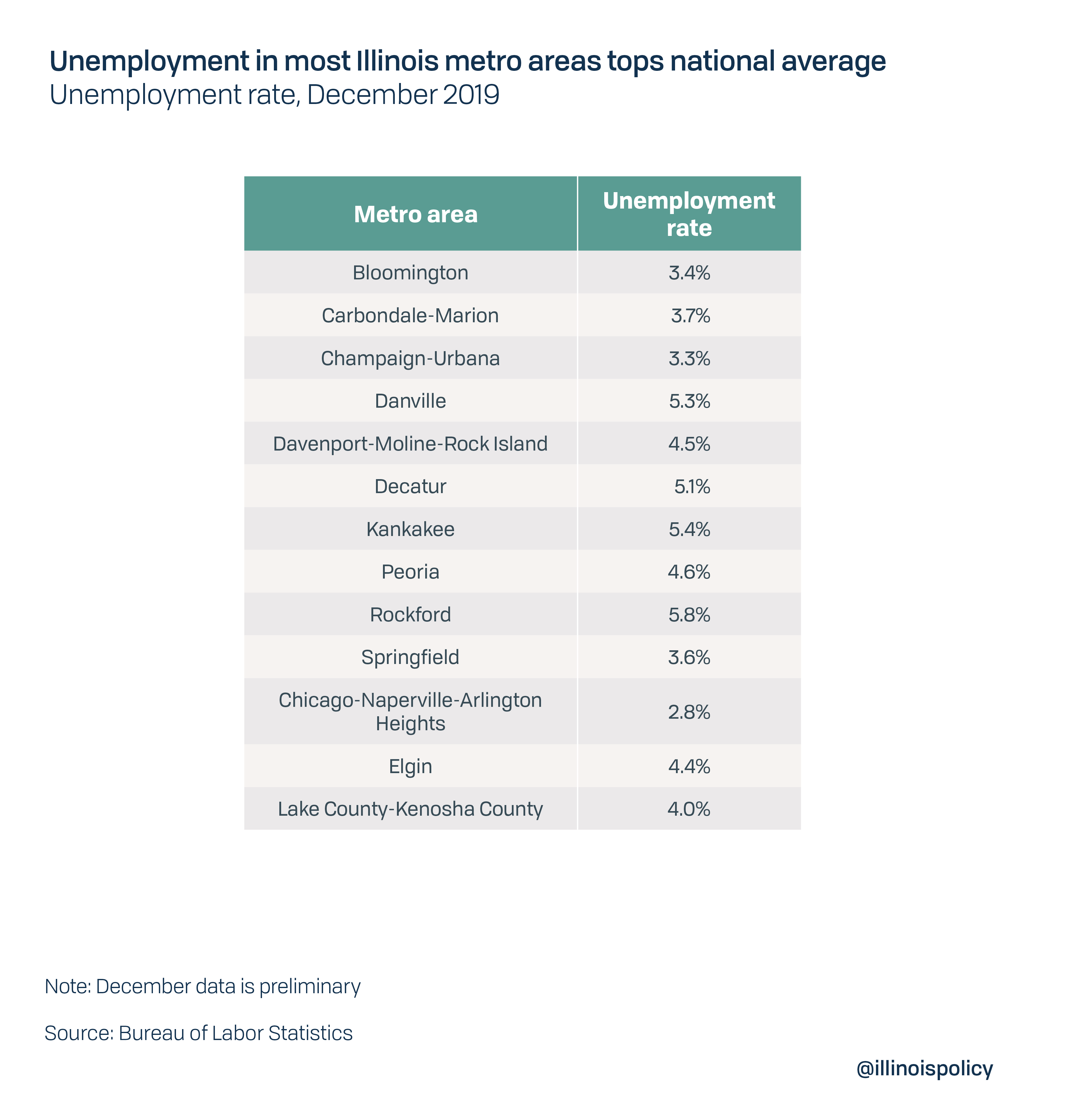

The governor’s administration has also praised record-low unemployment rates. In fact, sluggish employment growth has resulted in unemployment rates in nearly every Illinois metro exceeding the national average of 3.5%.

Only Bloomington, Champaign-Urbana and the Chicago-Naperville-Arlington Heights areas have unemployment rates below the national average. And while lower unemployment rates are a good thing, it is important to understand why unemployment rates have been declining throughout the state.

Illinois employment is down compared with before the recession. That means the decline in unemployment rates since then has been entirely from Illinoisans exiting the workforce.

This has been the case in nearly every metropolitan area throughout the state.

A declining labor force has been the sole reason for the declining unemployment rate in every Illinois metro except for Kankakee and Lake County-Kenosha County. While there has been some employment growth in Kankakee, the primary reason for the decline in the unemployment rate is still a shrinking labor force. Meanwhile, the Lake County-Kenosha County area, which includes part of Wisconsin, is the only metro area that has experienced a decline in unemployment rates solely because of employment growth.

A shrinking labor force will continue to pose challenges for expanding employment and lowering the joblessness rate in Illinois’ struggling labor market. Reversing the decline of the state’s prime working-age population and providing confidence for families and businesses to invest in the state is the only way to buck Illinois’ trend of comparatively lackluster employment outcomes.

State spending isn’t the answer

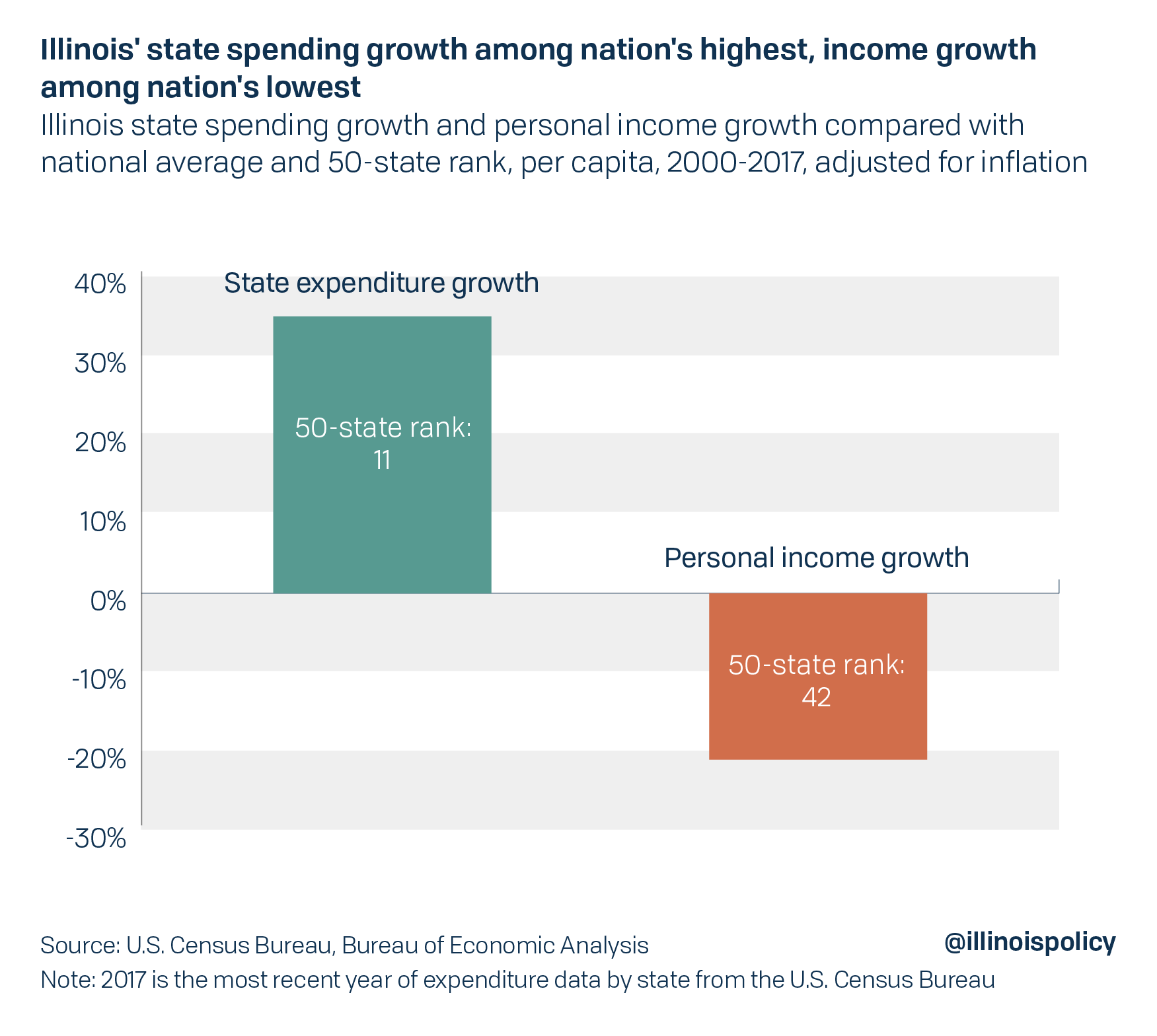

While Pritzker also touted his work to pass the largest budget in state history – $40 billion – and his $45 billion infrastructure plan as steps toward improving outcomes for Illinoisans, massive increases in state spending have not been accompanied by improved economic performance.

In the past two decades, state governments in every state have increased per capita state spending, even after adjusting for inflation. However, the growth in state spending varies widely among U.S. states. Since 2000, Illinois has increased per capita state spending 35% faster than the national average, the 11th-fastest rate in the nation.

Proponents of increased government spending would say this increase in state spending is good for the state’s economy, and Illinois should continue to pursue large increases in spending. But the evidence is sparse that the abnormally large increase in state spending has led to significant benefits for Illinois compared to other states.

Since 2000, per capita personal income in Illinois has only grown by 18% after adjusting for inflation. That’s 21% slower than the national average and among the bottom 10 states nationally.

Despite Illinois’ above-average increase in state spending per capita, personal income growth per person has been among the lowest in the nation. Proponents of increased government spending would expect the increase in spending to be associated with a large increase in personal income: Government funds are often used for education that can improve the quality of the workforce, protective services to ensure public safety and order, and infrastructure which can also improve efficiency within markets. However, the empirical evidence for the benefits of government spending are mixed at best.

As outcomes for Illinoisans continue to lag other states, it is clear that increased government spending and payrolls are not the solution to Illinois’ weak economy and are likely causing the state to shed jobs it would have otherwise added. Instead, the state needs to pursue policies that foster a healthy environment for private sector jobs to grow.

Real solutions

Recent tax hikes have already fostered an environment in Illinois that makes it harder for Illinoisans to find work and reduces wage growth prospects for those who are employed. While the rest of the nation has experienced robust employment growth in the past decade, with payrolls far exceeding their 2007 levels, Illinois has struggled to add jobs. Since 2007, Nearly half of Illinois’ metropolitan areas have shed jobs, and those that have been growing have severely lagged the national average rate of jobs growth.

Adopting the governor’s progressive income tax proposal would prolong the state’s labor market troubles, likely costing the state thousands of jobs and encouraging even more Illinoisans to exit the workforce. Instead of again asking taxpayers for more, lawmakers need to pursue real reforms that would put the state on firm fiscal footing and give much-needed certainty and tax relief to families and businesses.

First, Illinois must address its pension problem, which continues to grow despite two record income tax hikes within the past decade. Though pensions take up more than 25% of Illinois’ general fund expenditures, the state pension funds’ debt is growing. But by amending the Illinois Constitution to allow for adjustment of the growth rate of not-yet-accrued benefits, the state can reduce pension debt and ensure the plans can support retirees without overwhelming taxpayers. Such changes could include increasing the retirement age for younger workers, tying annual benefit increases to the actual cost of living and making retirement plans more closely resemble 401(k)s for new workers.

Second, a spending cap could help the state meet Illinois’ constitutional balanced budget requirement, which has been ignored for nearly 19 years. One interesting proposal would be a smart spending cap that ties government spending growth to a measure of what Illinois’ taxpayers can afford, such as growth in state gross domestic product or personal income. Texas and Tennessee have implemented something similar to this, and both have budget surpluses, no state income tax and lower property tax rates than Illinois.

Responsible government spending growth that taxpayers can afford would provide more stability for families and businesses. But if the state substitutes tax hikes for necessary reforms, Illinois can expect to continue enduring sad labor market outcomes compared to other states.