The Policy Shop: How bad is Illinois’ pension problem?

This edition of The Policy Shop is brought to you by Director of Fiscal and Economic Research Bryce Hill.

Three years ago, Illinois state lawmakers wrote to Washington, D.C., asking for a favor. Nothing major. Just $40 billion.

A cool $10 billion to bail out state and local public pensions, plus extra to prop up the state budget, the state’s unemployment insurance fund and more.

The feds declined to fix the pension mess Illinois leaders created, and state leaders never pursued reforms to fix Illinois’ pension problems. Today, we owe $211 billion in unfunded state and local pension liabilities.

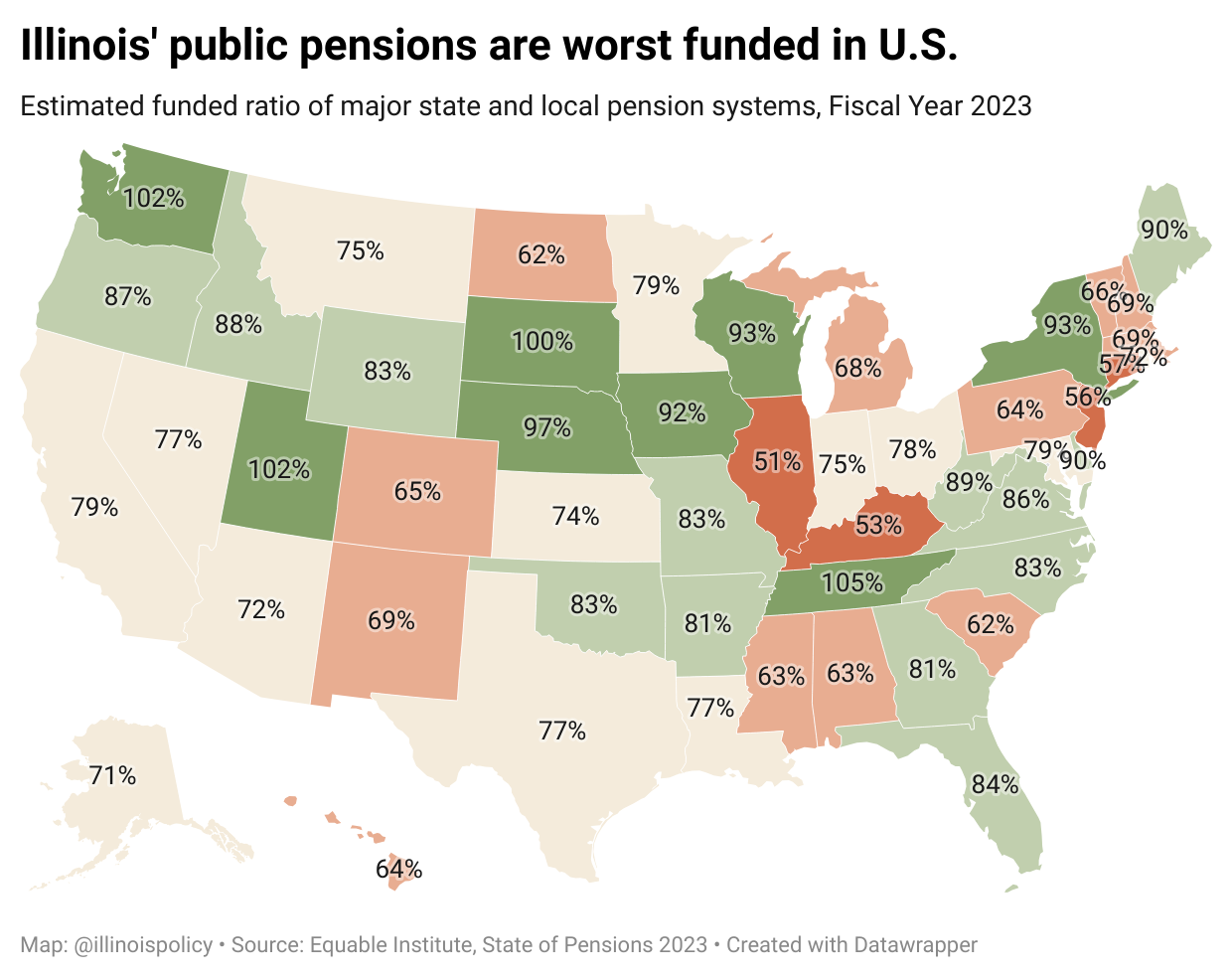

Our funding ratio for these pensions is 51% – the worst of any state. Experts warn pensions with funding ratios below 60% are deeply troubled and plans with funding ratios below 40% are likely past the point of no return.

Yeah … it’s a problem.

Yeah … it’s a problem.

Deeply troubled – Gov. J.B. Pritzker and others are touting Illinois’ financial improvements, but a new report by Equable Institute shows just how little improvement has been made on Illinois’ biggest financial problem – pension debt. The report examined state and local pension debt across all major state and municipal pension plans, with the analysis confirming Illinois’ pension crisis is the worst in the nation.

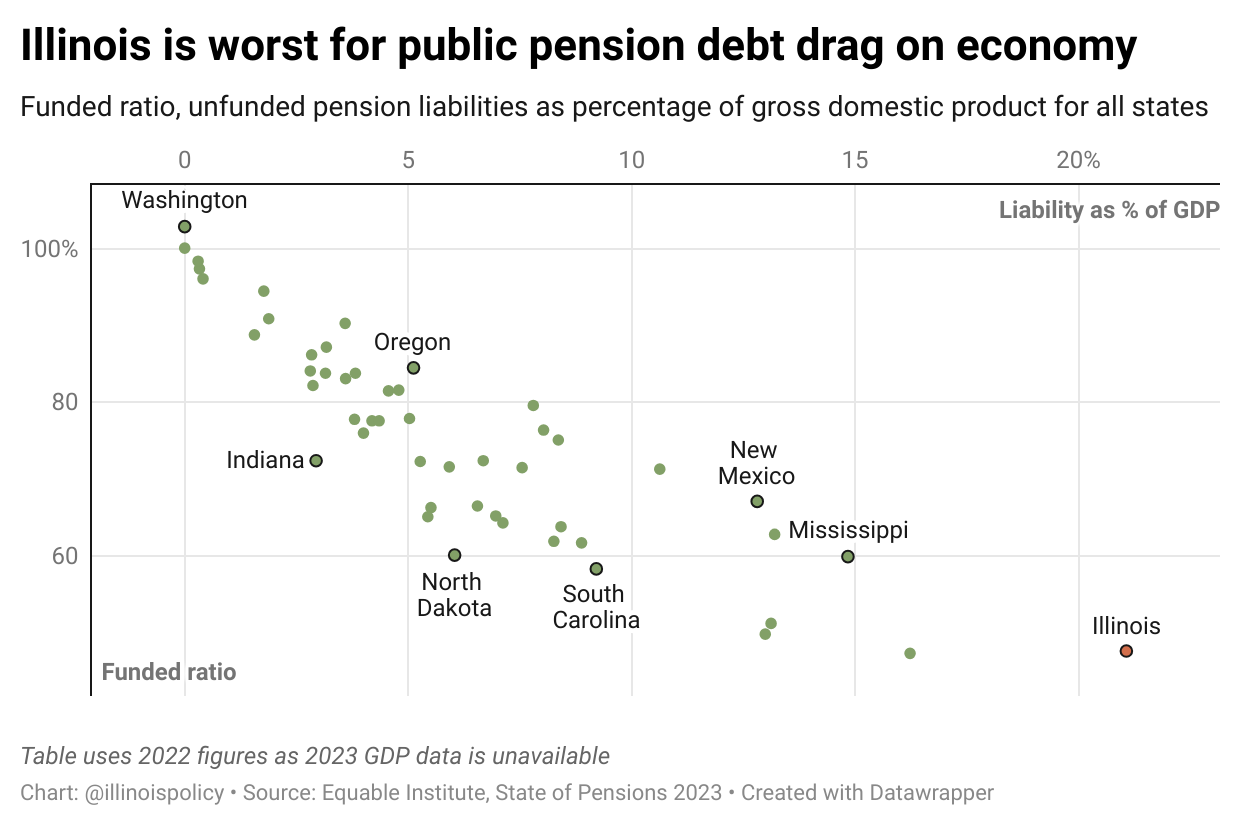

The report also looked at other metrics to add context to the pension debt issue for states. It shows Illinois’ unfunded liabilities as a percentage of its gross domestic product – a proxy for a state’s ability to pay – stand at 21%, by far the worst figure in the nation. It was nearly five percentage points higher than the second-worst figure of 16.2% in Kentucky. The vast bulk of states, 42, had unfunded liabilities as a percentage of GDP lower than 10%.

Not only are Illinois’ pension systems most likely to default, but Illinois also has the lowest capacity to pay the debt compared to other states.

Not only are Illinois’ pension systems most likely to default, but Illinois also has the lowest capacity to pay the debt compared to other states.

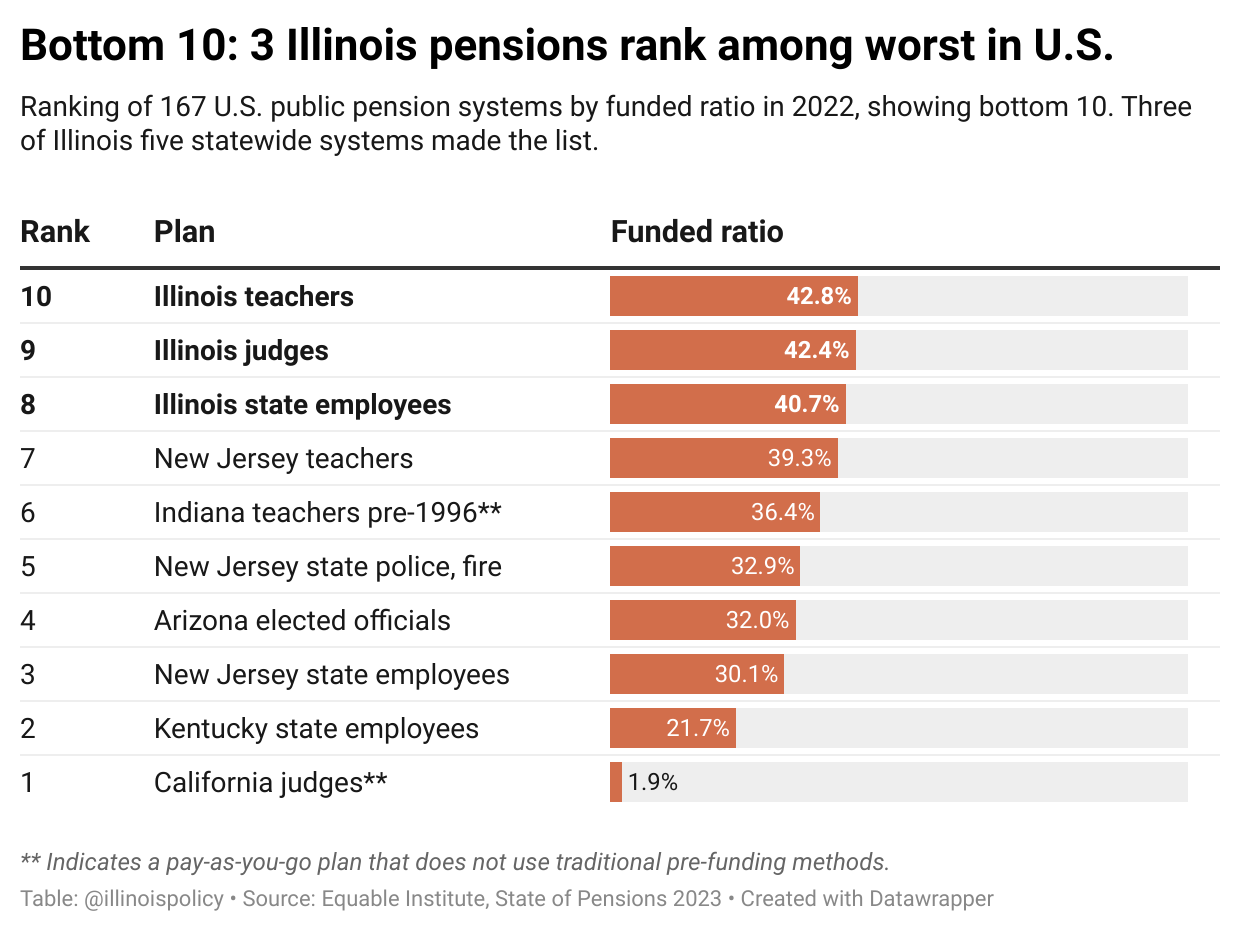

Bottom 10 – The bad news in the report didn’t stop there. Of the 167 statewide pension systems whose market returns for 2022 were analyzed, three of Illinois’ five state-run retirement systems were among the 10 worst-funded systems in the nation. Last year’s pension report showed two Illinois systems in the bottom 10 nationally, the State Employees’ Retirement System and Teachers’ Retirement System. This year, the Judges’ Retirement System joined them among the worst-funded systems in the nation.

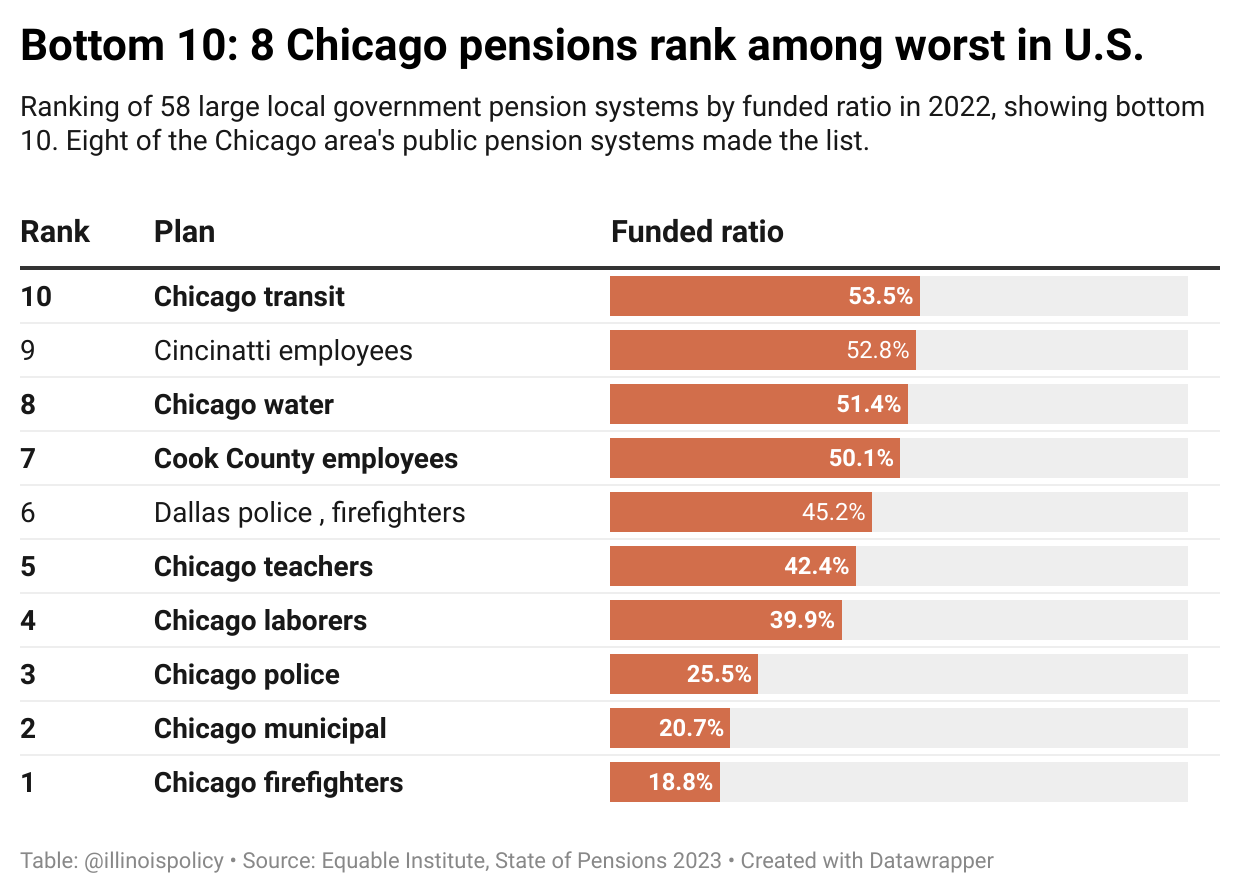

Mayor Johnson, take note – Bad turns to worse for local pension systems in Illinois. Of the 58 major municipal pension systems analyzed, eight of the 10 worst-funded systems were in Chicago or Cook County, including the five bottom systems.

Mayor Johnson, take note – Bad turns to worse for local pension systems in Illinois. Of the 58 major municipal pension systems analyzed, eight of the 10 worst-funded systems were in Chicago or Cook County, including the five bottom systems.

Mayor Brandon Johnson formed a working group with the stated purpose of collaborating on ideas to solve the city’s pension crisis. The working group includes state lawmakers and labor leaders, but excludes any business leaders.

Mayor Brandon Johnson formed a working group with the stated purpose of collaborating on ideas to solve the city’s pension crisis. The working group includes state lawmakers and labor leaders, but excludes any business leaders.

“We can make Chicago safer, grow Chicago businesses, create good jobs, strengthen public schools for all of our kids, protect our environment, improve mental health, and fix our broken transportation system — without raising property taxes,” according to Johnson’s campaign platform.

Johnson will be hard pressed to keep his promise on property taxes. His pensions working group better have some magic up its sleeve (or, you know, they’re willing to consider reasonable approaches to reforming the system that protect already-earned benefits but allow for adjustments to future benefits).

Illinois’ ESG mandate prompts riskier pension investments – Massive pension debt and poor funding ratios have coincided with pension systems taking on riskier alternative investments. Illinois’ pension systems had over $65 billion – the sixth-most in the nation in nominal terms – invested in alternative asset classes such as private equity, real estate, hedge funds and commodities at the end of fiscal year 2022. These alternative investments represented one-third of all assets held by Illinois’ public pension systems. While they can offer greater diversification, they also carry a greater degree of risk and returns can vary widely.

This could be especially troubling given Illinois is the only state to mandate environmental, social and governance considerations – known as ESG – to be factored into public investment decisions. ESG investments have not only been shown to yield lower returns than traditional investments, but companies in ESG portfolios have also had worse compliance records for both labor and environmental rules. Critics of ESG investing have cited concerns over the politicization of investment decisions and alleged the concept violates the fiduciary duty of investment managers.

The way forward is clear – And it’s not just continuing what we’re doing today (the state’s current funding plan shorts statewide pension systems by more than $4 billion annually).

Tax hikes won’t work. Illinois is already home to a high-tax and uncompetitive business climate. Pritzker and lawmakers have aggravated those trends. Illinois’ business tax climate continues to lag behind regional neighbors and most other states. The tax climate has led to an exodus of businesses, jobs and wealth from the state. It has also forced residents to leave in record numbers. Data shows Illinoisans of every age and income bracket are fleeing the state, taking with them $11 billion in income each year.

Still, state lawmakers aren’t doing anything about the problem. S&P Global Ratings recently warned the state isn’t doing enough to address its pension liabilities.

“We believe pensions have an elevated probability of stressing the state and local governments,” the report says. “Costs will keep rising because contributions are significantly short of meaningful funding progress, plans are poorly funded, and the Illinois Pension Code allows plans to use assumptions and methodologies that defer costs.”

Only structural pension reforms enabled through a constitutional amendment can truly turn state finances around. A “hold harmless” pension reform plan such as one originally developed by the Illinois Policy Institute – based loosely on bipartisan 2013 reforms – could help to eliminate the state’s unfunded pension liability and achieve retirement security for pensioners.

Previous analysis showed changes such as capping pensionable salary, replacing 3% compounding raises with true cost-of-living increases and adjustments to realign benefits with historical inflation rates would have saved the state $2.4 billion in the first year alone, and more than $50 billion by 2045. It would also fully fund the plans, as opposed to the state’s goal of 90% funding, to truly safeguard retirees’ benefits.

Sounds pretty good to us.