The Policy Shop: How bad public education keeps people poor

This edition of The Policy Shop is by policy analyst Hannah Schmid.

Third grade is a critical point in a child’s education. Their futures are often locked in by their ability to read at the end of that year.

The chances of graduating high school can be predicted at that point.

Their future earnings as adults may be set.

That’s because children learn to read in third grade. But in fourth grade they start reading to learn. If they can’t read, they can’t understand and the printed fourth-grade curriculum becomes gibberish to them, according to a Children’s Reading Foundation study.

An Annie E. Casey Foundation study warned: “If we don’t get dramatically more children on track as proficient readers, the United States will lose a growing and essential proportion of its human capital to poverty, and the price will be paid not only by individual children and families, but by this entire country.”

If your eyebrows just raised at that, prepare to get wide-eyed.

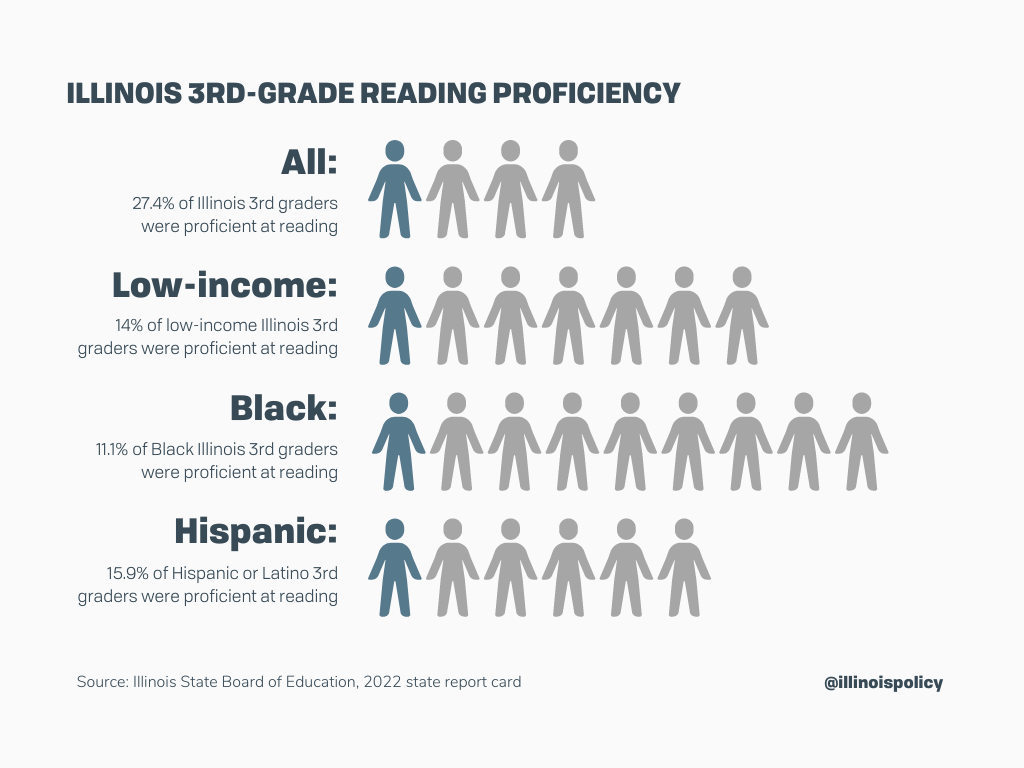

Just over one-fourth of all third-grade students in Illinois can read at grade level. For low-income and minority students, reading proficiency is even worse.

Only 27.4% of all Illinois students could read at grade level by the end of third grade in 2022. Of the 734 school districts for which the Illinois State Board of Education recorded proficiency rates among third graders, 89% had a higher percentage of third-grade students failing to read at grade level than reading at grade level. There were 12 school districts in which no third-grade students read at grade level.

If a student comes from an impoverished family, the stats are even worse.

Just 14% of low-income third-grade students were proficient at reading.

Minority third graders also struggle to read in Illinois. Just 11.1% of Black third-grade students could read at grade level in 2022.

Statewide, just 15.9% of Hispanic or Latino third-grade students were reading at grade level.

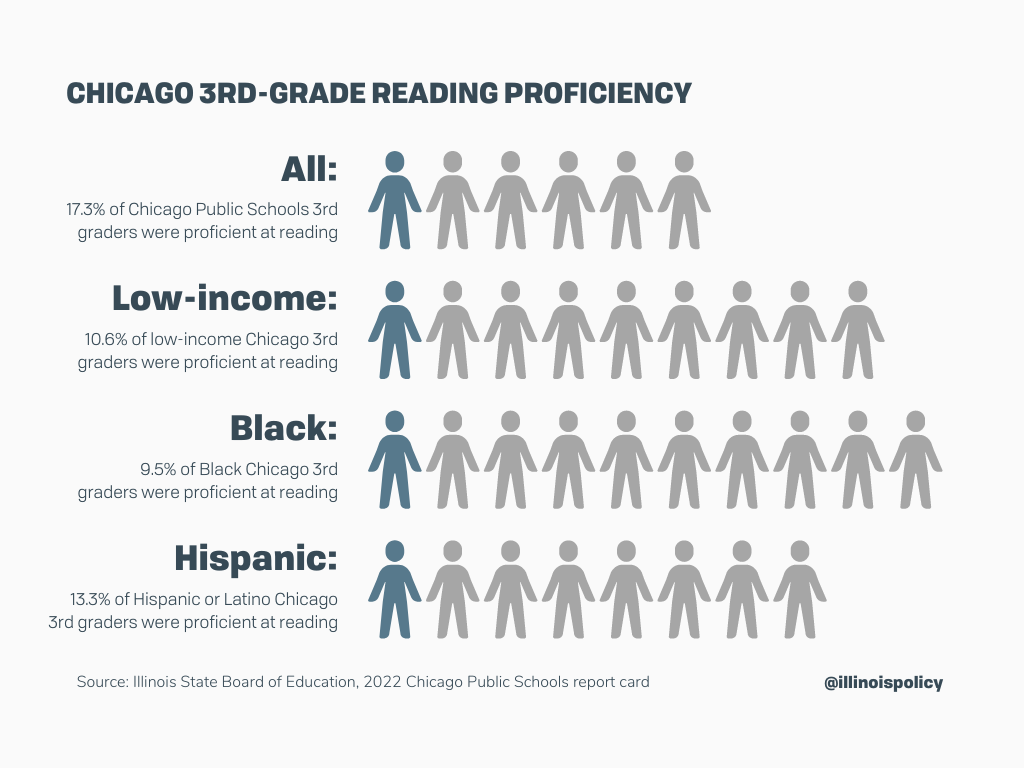

And as you might have guessed, things are worse in the state’s largest school district: Chicago Public Schools.

Just 17.3% of Chicago students could read at grade level by the end of third grade in 2022. There were 82 schools in which no third-grade students were proficient at reading.

Again, things are tougher if students come from an impoverished or minority family.

Just 10.6% of low-income third-grade students in Chicago were reading at proficiency. In 91 schools, not a single low-income, third-grade student could read at grade level.

Just 9.5% of Black third-grade students could read at grade level. In 30% of the schools with proficiency for Black third-grade students, no Black third-grade students could read at grade level.

Just 13.3% of Hispanic or Latino third-grade students could read at grade level.

So what does it all mean to you? A dimmer future as too many Illinois children fail to advance academically and professionally.

Poor third-grade literacy lowers earning potential if they fail to graduate high school. The median annual earnings of adults ages 25 through 34 who had not completed high school were lower than the earnings of those with higher levels of educational attainment, according to data from the Census Bureau’s 2017 Current Population Survey.

The unemployment rate for high school dropouts was 13% compared to the 7% unemployment rate of those whose highest level of educational was a high school credential. A dropout’s median weekly pay was $682 compared to $853 for a high school diploma and $1,432 for a college grad in 2022.

Education also makes major differences in poverty rates, with each higher level of educational attainment being associated with lower instances of poverty.

There’s a price tag attached to failing to help a third-grader learn to read: $272,000. The average high school dropout cost the economy that much over a lifetime compared to individuals who complete high school because of “lower tax contributions, higher reliance on Medicaid and Medicare, higher rates of criminal activity, and higher reliance on welfare,” the National Center for Education Statistics reported.

It's not third graders failing. It’s not us failing third graders. It’s us failing ourselves when third graders move on without being able to read.