$31.6 billion is more than what Illinois spends on all core government services (e.g., education, health care, human services, public safety) in a full fiscal year.

In 2011, Illinois had an $8.5 billion bill backlog.

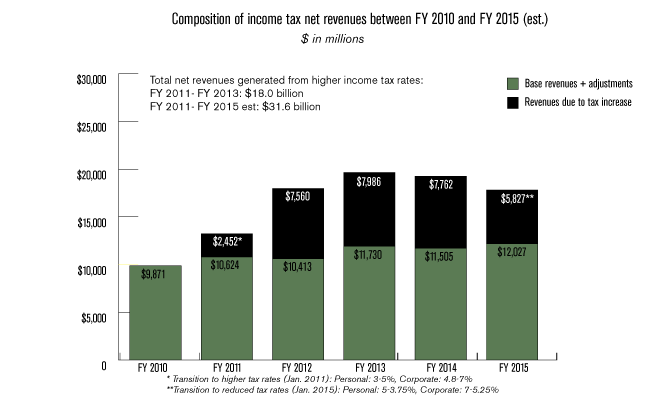

In the same year, lawmakers increased income taxes, which will transfer an extra $31.6 billion from taxpayers to government during the first five years.

But in 2014, Illinois has a $7 billion bill backlog.

The math just doesn’t add up.

Even though state government will have at its disposal what amounts to nearly an entire extra year’s operating budget, the amount of past-due bills dropped by only $1.5 billion since the tax hike.

As the sunset of the tax increase approaches in January 2015, state leaders are crying “catastrophe” and demanding that Illinois families and businesses pay more to government.

Taxpayers have had enough of tax increases and the enabling of reckless spending. Illinois has a spending problem, not a revenue problem.

Illinois lawmakers in January 2011 pushed through a record income tax increase that raised the income-tax rate on individuals to 5 percent from 3 percent, and on corporations to 7 percent from 4.8 percent. They called it the Taxpayer Accountability and Budget Stabilization Act and went on record making the following promises:

“We have some temporary tax increases that are designed to pay our bills, get Illinois back on fiscal sound footing and make sure that our state has a strong economy.” – Gov. Pat Quinn

“The purpose of this bill is to raise enough money so that we can continue to pay our pensions without borrowing the money, to pay off our debt, to have enough money to pay the interest on that debt …” – Senate President John Cullerton

“… remember the point of this income tax increase is not to expand programs, not to do brand new things in Illinois state government, it is only intended to pay our old bills and deal with the structural deficit.” – House Majority Leader Barbara Flynn Currie

Illinois’ political leaders said the goal of the tax hike was to pay down the state’s backlog of bills, stabilize the state’s pension crisis and strengthen its economy. Yet the state’s pension debt and backlog of bills continue to hover at unsustainable levels.

Illinois’ political leaders said the goal of the tax hike was to pay down the state’s backlog of bills, stabilize the state’s pension crisis and strengthen its economy. Yet the state’s pension debt and backlog of bills continue to hover at unsustainable levels.

It’s not for a lack of revenues.

Between 2011 (when the tax hike was implemented) and 2015 (when the tax hike will partially sunset), the tax hike will have generated $31.6 billion in new, additional revenue for the state of Illinois.

To put that number into perspective, $31.6 billion is more than what Illinois spends on all core government services (e.g., education, health care, human services, public safety) in a full fiscal year.

Even with all of this extra money, Illinois’ finances are still a disaster. The extra revenue has only allowed lawmakers to skirt meaningful reforms as the state’s fiscal crises continue to worsen.

Unpaid bills: $7 billion remains

In January 2011, the month the tax hike was passed, Illinois’ unpaid bills totaled $8.5 billion. By 2015, the tax hike will have generated nearly four times the revenue needed to pay down the bill backlog. Yet Illinois Comptroller Judy Baar Topinka estimates that Illinois’ backlog of unpaid bills currently stands near $7 billion.

Interest payments: 3.5 times higher than 2011

Illinois is required by law to pay interest of 1 percent per month on its unpaid bills when they become more than 90 days old. In 2011 the interest payments on Illinois’ unpaid bills totaled $53 million. By 2013 that number had grown to $240 million, or 3.5 times more than what the state paid in 2011.

Credit rating: downgraded five times since the tax hike

Illinois has been downgraded five times since the 2011 tax hike – twice by Moody’s Investors Service, twice by Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services and once by Fitch Ratings. Now Illinois stands only four notches away from junk-bond status. The additional revenue that allowed lawmakers to avoid real spending reforms only worsened the state’s fiscal footing.

Pension debt: still unsustainable

Despite dumping billions of the additional tax-hike revenue into the state’s pension systems, Illinois’ pension systems are still among the worst in the nation. And the pension reform passed by the Illinois General Assembly in 2013 did little to stabilize Illinois’ pension crisis.

At best, Illinois’ recent pension bill reduces the state’s unfunded liability to 2011 levels – levels that had already thrown Illinois into crisis and that Democrat leadership used as justification for its 2011 tax hike in the first place.

Unemployment: third-highest in the nation

In January 2011, the same month as the tax hike, Illinois’ unemployment rate was similar to the national average – both at more than 9 percent. In December 2013, Illinois’ unemployment rate stood at 8.9 percent while the national average had dropped to 6.7 percent.

Food stamps: more people to food stamps than to payroll jobs

Illinois added more people to food stamps than payroll jobs since January 2011. Illinois has added nearly 200,000 people to its food-stamp rolls while adding only 186,000 payroll jobs since the 2011 tax hike. ,

The tax hike failed

Lawmakers sold the 2011 tax hike as a “temporary” increase. The individual income-tax rate was increased to 5 percent from 3 percent and is required to sunset to 3.75 percent in 2015, and again to 3.25 percent in 2025. The corporate income-tax rate was increased to 7 percent from 4.8 percent, and is required to sunset to 5.25 percent in 2015 and again to 4.8 percent in 2025.

But now the 2015 sunset date is closing in and politicians are trying to backtrack on that promise with efforts to make the tax hike permanent.

- Illinois House Deputy Majority Leader Lou Lang, D-Skokie, introduced legislation that would make the 2011 income tax hike permanent and use the higher taxes to make pension payments. Lang thinks it’s a no-brainer: “I don’t think there’s anyone in this building who doesn’t believe we need to extend the income tax increase.”

- State Rep. Elaine Nekritz, D-Northbrook, agrees: “Including the income tax increase as part of the solution, to me, is already being part of the solution.”

- And Senate President John Cullerton, D-Chicago, says it’s time to honestly face the future about sunsetting the 2011 tax hike. Cullerton said making it permanent isn’t a lie because: “Gov. [Jim] Edgar proved that you don’t have to lie. You can say that I think we should keep it at a certain rate.”

The more than $31 billion in extra money that Illinois families and businesses will have turned over to government by the end of 2015 has done little to stabilize Illinois’ finances.

More of the same isn’t going to fix persistent structural overspending issues.

If you give an Illinois politician a tax hike, he is bound to want another one – regardless of how he wasted the first one.

The fact is Illinois doesn’t have a revenue problem; the state has a spending problem.