Plan for over 640 police, fire pensions barely touches Illinois’ $200B problem

Consolidating downstate and suburban police and fire pension systems is a start, but both fixes and Illinois’ pension problems go much deeper.

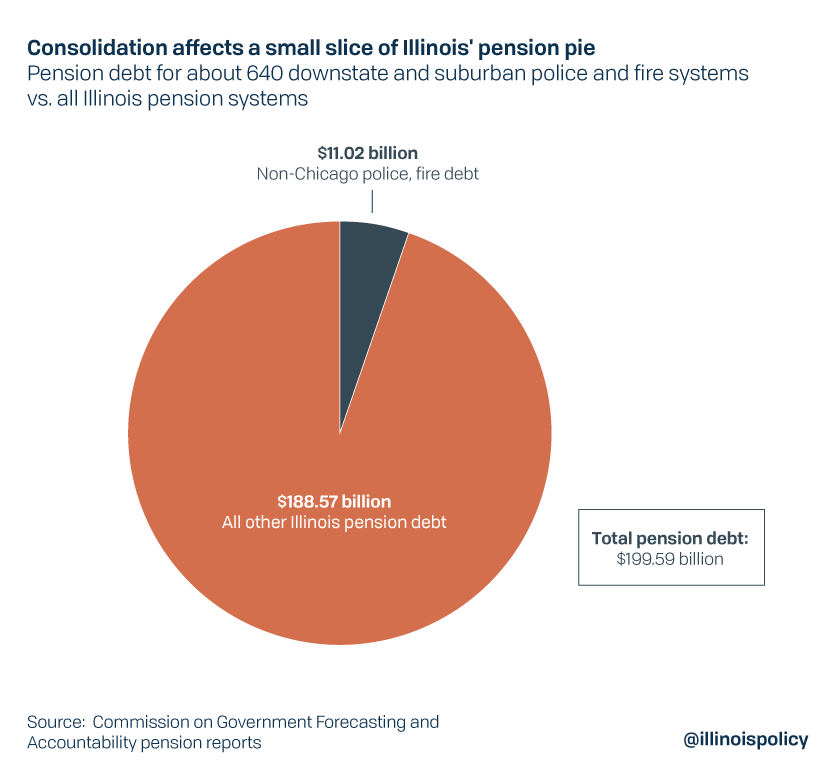

Consolidating investments of over 640 of 667 Illinois public pension funds sounds like major progress, but a closer look shows a new report’s recommendations touch only about 5.5% of the state’s nearly $200 billion pension debt.

Plus, that false perception of progress could be used to smother efforts to fix the remaining 94.5% of Illinois’ pension problem.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker’s task force on pension consolidation issued the report that recommends merging assets of over 640 police and fire pension funds outside of Chicago that hold a little more than $11 billion in pension debt. One fund for police and another for firefighters would be created, but more than 640 systems’ overhead and administrative functions would remain.

While the proposal is a step in the right direction, it targets just a small fraction of the problem and falls far short of fully solving it. Plus, the greater risk to taxpayers would be for the consolidation proposal to pass and be used as an excuse for Springfield to wash its hands of the pension problem and pretend they’d fixed it.

In reality, Illinois would be only slightly better off if this plan were enacted.

What to know about consolidation

Consolidation of pension funds has two main upsides. First, larger pools of assets – money held in the fund and invested to generate income – can achieve greater returns by attracting more professional investment managers and leaving more room to diversify investment portfolios. Second, consolidating the boards and administrative functions of the various pension systems could reduce costs through economies of scale. Having over 640 different funds leads to duplication in accounting, legal and other functions because each system has its own board of trustees and separate support staff.

Unfortunately, Pritzker’s report stops short of recommending consolidation of benefit administration. It focuses only on the first benefit: investment pools. An independent analysis from the Anderson Economic Group in 2018 found that administrative savings could be as much as $21 million annually under full consolidation. Pritzker’s plan gives up much of those potential savings.

The task force estimates that higher investment returns could bring in an additional $160 million to $288 million in annual investment revenue. If true, this would reduce pressure on taxpayer contributions because local systems are mostly funded though property taxes.

However, it’s unclear whether such a significant jump in returns could actually be realized. The report compares average investment returns from fiscal year 2004 to fiscal year 2013 among downstate police and fire funds, the Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund (IMRF), and Illinois statewide systems. The police and fire funds achieved an average return of just 5.61% over those years. By comparison, IMRF achieved 7.62% and the state systems achieved 6.73%, which the report used as the basis for the high-end and low-end estimates of what the police and fire systems could have potentially achieved.

Comparisons to IMRF are overly optimistic. While IMRF is a consolidated system for all municipal employees other than public safety workers, it is different in other ways that are significant for its investment returns. IMRF is significantly better funded than either the state systems or the police and fire systems, with a 93% funded ratio – the amount of money on hand to cover current and expected future benefits – and nearly $40 billion in assets. For comparison, the collective funding ratio for downstate police and fire is just 55% with just under $14 billion in assets. A smaller asset pool and a lower funding ratio impair a fund’s ability to achieve high returns by limiting diversification and risk exposure.

Experts generally recognize that a funding ratio of less than 60% means a plan is “deeply troubled” while 40% may be a point of no return, meaning funds with such low ratios might never be able to pay off their debts without structural changes.

The state systems have similarly bad funding ratios to the public safety systems, though they still have much more in asset value, making the low-end $160 million figure the more probable outcome. However, even this target is uncertain. Experts warn of slowing investment returns and economic growth in the U.S. and globally over the coming decades.

The only real answer to Illinois’ pension crisis is a constitutional amendment that protects earned benefits but allows for changes to future benefit growth. Without such a change, Illinoisans face a future in which they are asked to pay more to receive less in services