Pension funds’ rosy projections spell trouble for Illinois taxpayers

Overly optimistic expectations about investment returns mean Illinois is understating its pension debt. That could lead to a nasty surprise for future taxpayers.

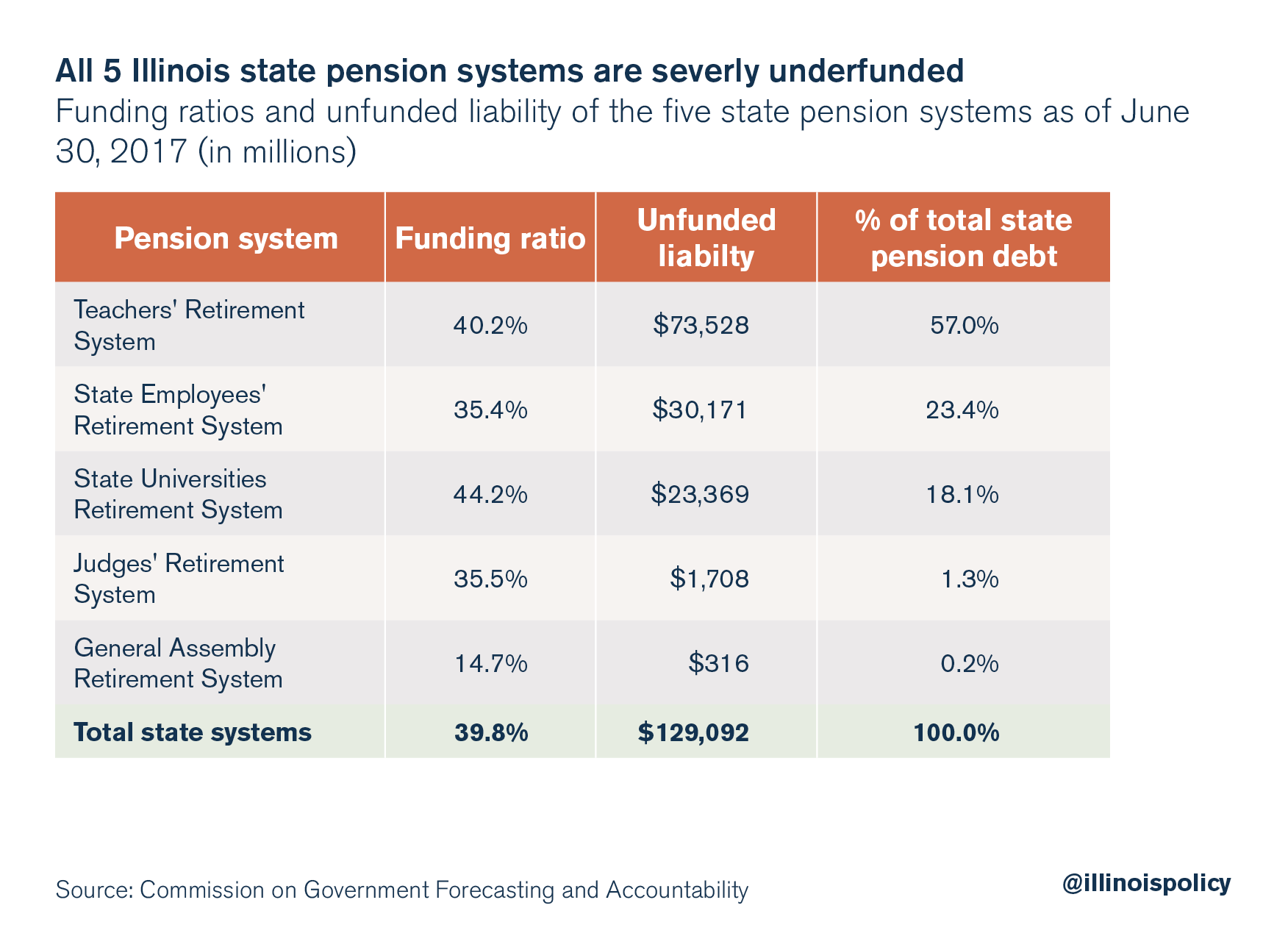

Illinois’ pension funds are in the worst shape of almost any state pension system in the nation. The state estimates its unfunded pension liability at nearly $130 billion.

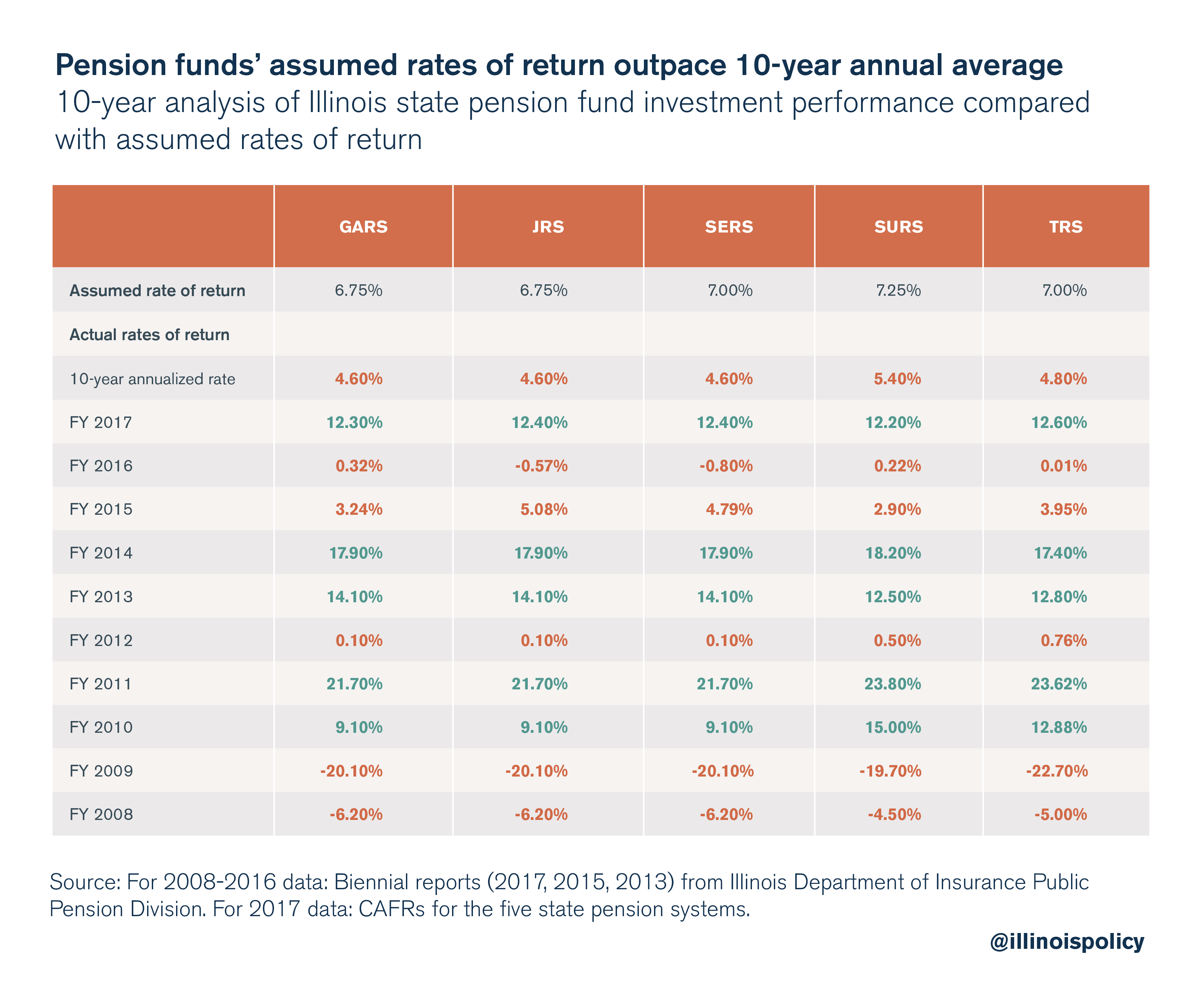

But the real number is likely even higher. If pension systems do not accurately gauge the rate of return they will receive on their investments, they overstate the future value of their assets and understate the size of the liability. Illinois’ five state pension systems currently assume rates of return between 6.75 percent and 7.25 percent per year. But the 10-year average annual returns for all five systems fall short of those targets, meaning they could be unrealistically high.

Lowering the pension systems’ assumed rates of return to more realistic levels would reveal the true extent of Illinois’ fiscal mess, and it won’t be a pleasant topic for politicians who prefer to sidestep the issue. Doing so would increase the state’s nearly $130 billion of pension debt, on paper. But the taxpayers on the hook to cover the debt, and policymakers who want to address the problem, need to know just how severe the crisis is.

Pension fund returns fall short of assumptions

Illinois’ five state systems have reduced their assumed rates of return in recent years. In 2008, three of the systems used a rate of 8.5 percent. While the rates have come down to more realistic levels, Illinois taxpayers should be concerned that they are still too optimistic.

Annual returns can fluctuate wildly. And the medium-term returns – measured as the 10-year annualized rates of return through fiscal year 2017 – have fallen significantly short of assumed rates. This means the amount of money earned by the pension funds through their investments was less than expected, putting taxpayers on the hook for the difference.

The decade of the 2010s has thus far been good for investors, but there is no guarantee that this will last. Only the decades of the 1950s and 1990s, bolstered by a post-World War II economic boom and the dot-com era, respectively, have exceeded the stock market returns realized during the 2010s, according to MarketWatch. Federal Reserve policies have kept interest rates at historic lows during this period, which has juiced the economy and financial markets. Maintaining such performance over the next 10 years will be a challenge.

What does this mean for Illinois’ state pension systems? Moody’s Investors Service, which uses a low discount rate based on high quality corporate bond index, estimated the state’s net pension liability increased to $250 billion, almost double the state’s estimate, in fiscal year 2017. A recent report by Michael Cembalest at J.P. Morgan Asset Management shows public plans use an average rate of 7.1 percent to discount pension liabilities, compared with corporate plans that use a much lower average rate of 3.6 percent.

It is highly unlikely that Illinois, or any other state for that matter, would immediately adjust to the Moody’s methodology. Still, the state could adopt Cembalest’s use of a 6 percent assumed rate of return based on a forward-looking 4 percent real return plus 2 percent inflation.

A 6 percent rate of return tracks more closely with the state pension systems’ actual 10-year investment performance. Using that discount rate would reduce Illinois’ pension funding ratio to 34 percent from just under 40 percent.

What is the assumed rate of return, and why does it matter?

The assumed rate of return is an estimate of what invested assets owned by pension funds will earn. Those earnings are crucial to the solvency of public pension plans because, on average, they account for over 70 percent of total nationwide public pension benefits that are paid, according to Peter Mixon of Pension & Investments.

However, the assumed rate of return serves another function that is unique to public pension plans, according to the Rockefeller Institute of Government. Public pension plans generally use the assumed rate of return as the so-called “discount rate” to calculate the present value of their pension liabilities.

The Rockefeller Institute of Government, a public policy think tank that is part of the State University of New York system, notes this practice is not shared by private sector pension plans and cautions that valuing pension liabilities should be separate from estimating what pension funds will earn on investments. Reason Foundation has also warned against substituting the assumed rate of return for the discount rate.

Nevertheless, most public pension plans do use the assumed rate of return as the discount rate.

According to Illinois’ Office of the Auditor General, the assumed rate of return, or what it calls the interest rate assumption, is the biggest factor in determining what the state must contribute to pension funds to ensure adequate cash is available to pay retiree benefits. According to the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability, or COGFA, the five systems had only $85 billion in their combined pension assets to pay $214 billion of accrued pension liabilities as of the fiscal year ended June 30, 2017. That’s a funded ratio of less than 40 percent.

There is much debate about whether it is appropriate to use the assumed rate of return as the discount rate. However, to the extent public pension plans do so, a question arises: is the assumed rate of return realistic compared to actual investment performance?

The answer: In Illinois, evidence suggests the pension funds’ projections are too optimistic.

Fixing the pension problem

Continuing to use inflated assumed rates of return only delays the day of reckoning for future lawmakers and taxpayers. Reducing the assumed rate of return would reflect Illinois’ pension liabilities more accurately, and although the hike in reported pension debt would likely cause lawmakers to resist such a move, taxpayers deserve to know just how big the pension bill is going to be.

Ultimately, Illinois must reform future pension benefits growth through a constitutional amendment to make the pension systems sustainable and affordable, ensure the retirement security of government workers, and protect taxpayers.