Pension debt for Chicago city-worker pensions doubles to more than $21 billion

Thanks to new government reporting standards, Chicago’s municipal-workers and laborers pension funds’ debt doubled in 2015 to more than $21 billion. That’s $20,500 of pension debt per Chicago household.

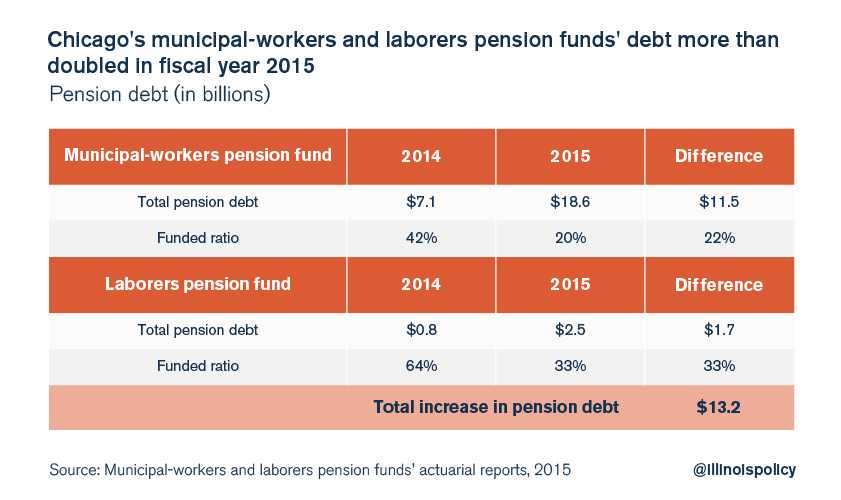

According to the 2015 actuarial reports of Chicago’s municipal-workers and laborers pension funds, over the last year Chicagoans have become saddled with an additional $13.2 billion in pension debt. The two city-run funds now owe more than $21 billion in unfunded liabilities – or $20,500 per city household.

The laborers pension system is now only 33 percent funded, down from 64 percent funded the year before, and the municipal workers pension system has less than a quarter of the money it needs to pay out future benefits.

By any measure, both funds are insolvent.

The doubling of the funds’ pension debt did not occur because of some unforeseen financial calamity or economic collapse. Instead, it occurred because the Governmental Accounting Standards Board, or GASB, the organization that establishes accounting and financial reporting standards for state and local governments, demanded that public pensions be more honest in their calculations.

GASB developed new government accounting standards that took effect in fiscal year 2015, which required public pension funds to use more realistic investment returns when running their numbers.

Think about it this way: If a pension fund assumes it can earn high investment returns in the future, then it needs less money in the present to fund its future pension benefits. In other words, artificially high investment return assumptions make a pension fund’s financial situation look better than it actually is.

But now that GASB is demanding that Chicago’s municipal-workers and laborers pension funds use a more realistic rate of return on investment, the funds are being forced to show the true extent of their financial woes – and just how much debt they’re piling on overburdened Chicagoans.

For example, the municipal-workers pension fund had to calculate its costs based on investment returns of 3.73 percent a year instead of the unrealistic 7.5 percent it usually assumes. That change more than doubled the fund’s pension debt, to $18.6 billion from $7.1 billion.

The amount of pension debt for which Chicagoans are on the hook will only get bigger when Chicago’s other two city-run pension funds – for police officers and firefighters – release their own actuarial reports for 2015.

Assuming the government’s new accounting standards affect the city’s police and firefighter funds similarly, Chicagoans could be on the hook for at least $44 billion in pension debt, or more than $43,000 per household.

This shows just how broken Chicago’s pension funds really are.

It will take bold reform to stabilize Chicago’s finances, protect city taxpayers, make government-worker retirements secure, and restore confidence in the city’s future.

Bold reform means a pension overhaul that protects what workers have already earned and empowers government workers with 401(k)-style retirement plans.

It means capping the growing debt burden and paying down existing debts in a responsible manner.

Finally, it means reining in spending and opening up union contracts to negotiate levels of benefits and wages according to what Chicago taxpayers can afford.

That’s the fiscal path Chicago needs to protect the future its residents deserve.