New proposal would hold schools accountable for ensuring students can read

Across the state, only 36 percent of third-grade black children read at grade level in 2014, while only 39 percent of Hispanic children met the standards. Yet state education rules force 4th grade children to advance to the next grade – whether they’re reading-ready or not.

Only 2 in 10 third graders can read at grade level at Carman-Buckner Elementary School in Waukegan, Illinois. That’s a severe problem for these kids, because “up to half of the printed fourth-grade curriculum is incomprehensive to students who read below that grade level,” according to the Children’s Reading Foundation.

The chance that students like those in Carman-Buckner drop out of high school rises dramatically.

Illinois House Rep. Rita Mayfield, D-Waukegan, has a plan to fix that problem. And not just for Waukeganites, but for all Illinois students.

Mayfield has proposed a bill to stop schools from automatically passing kids on to the fourth grade if they are not reading-ready. Her proposal would hold schools accountable for ensuring kids can read, breaking the practice of simply promoting students whether they are ready or not.

Mayfield knows the issue well. She previously served on the board of the Waukegan Community Unit School District 60, where more than 70 percent of students are low-income and nearly 75 percent are Hispanic.

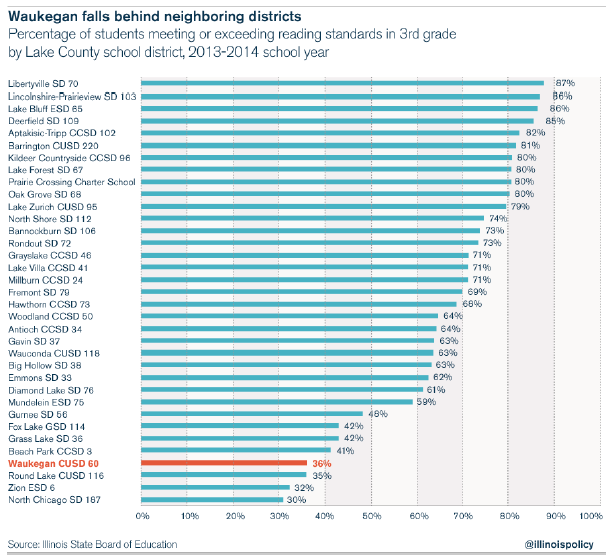

Only 36 percent of Waukegan third-grade students can read at grade level. That pales in comparison to neighboring districts in Lake County, where reading proficiency levels reach as high as nearly 90 percent.

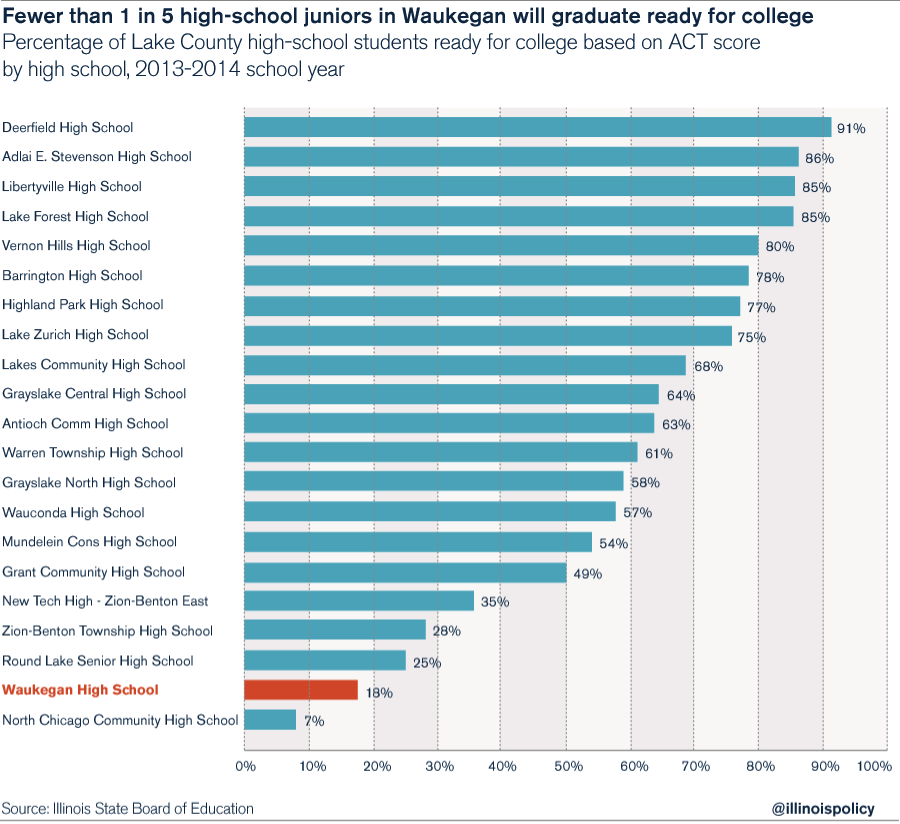

With such low reading scores during pivotal learning years, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that only 18 percent of Waukegan’s high-school juniors will graduate college- or career-ready, as determined by each student’s ACT score.

Waukegan is just one example of districts in which many students are suffering from poor reading scores. Across the state, only 36 percent of third-grade black children read at grade level in 2014, while only 39 percent of Hispanic children met the standards.

The gap between low-income students and their peers from higher-income families in Illinois in reading and math is alarming, and the overwhelming majority of Illinois’ low-income students aren’t graduating college- or career-ready. For many of these students, the learning gap will mean continuing hardship.

Research shows that students who lack basic math and reading skills are more likely to drop out of high school, are incarcerated at higher rates, are more likely to enroll in public-assistance programs and will make significantly less money than their peers who receive a quality education.

This gap has persisted over many years, but real reforms have been lacking. More money and a bigger bureaucracy for the public-school system have not led to positive results.

Some proponents of the status quo are quick to blame low-income parents and their children for poor educational outcomes, saying parents aren’t engaged and that children aren’t prepared. Others blame poverty and language barriers. Still others fault education funding as insufficient, despite the fact that per-student funding for education has grown at twice the rate of inflation in the last two decades.

Sadly, those excuses have led many schools to lower their expectations and move children right through the educational system, whether they are ready for the next grade or not.

Fortunately, states across the nation have begun the process to end automatic social promotion and to ensure that children are prepared for the future. In 2002, Florida implemented a law required that third-graders scoring the lowest on the state’s standardized test remain in third grade for another year. Research shows the students who were held back performed better on later standardized tests than their low-scoring peers who had been promoted to fourth grade.

Today, at least 15 states embrace a variation of Florida’s third-grade reading law.

Mayfield is right to insist that Illinois schools are held accountable for their students’ ability to read successfully, and that one-size-fits-all rules don’t set up children for frustration later in life. After all, as Dr. Shane Jimerson, a professor and Nationally Certified School Psychologist, has said: “children in kindergarten, first, second and third grade do not fail; their lack of academic success reflects the failure of adults to provide appropriate support and scaffolding …”