Most of Lake County’s largest communities are shrinking

Many communities in the northern Illinois border county are having trouble attracting and retaining residents.

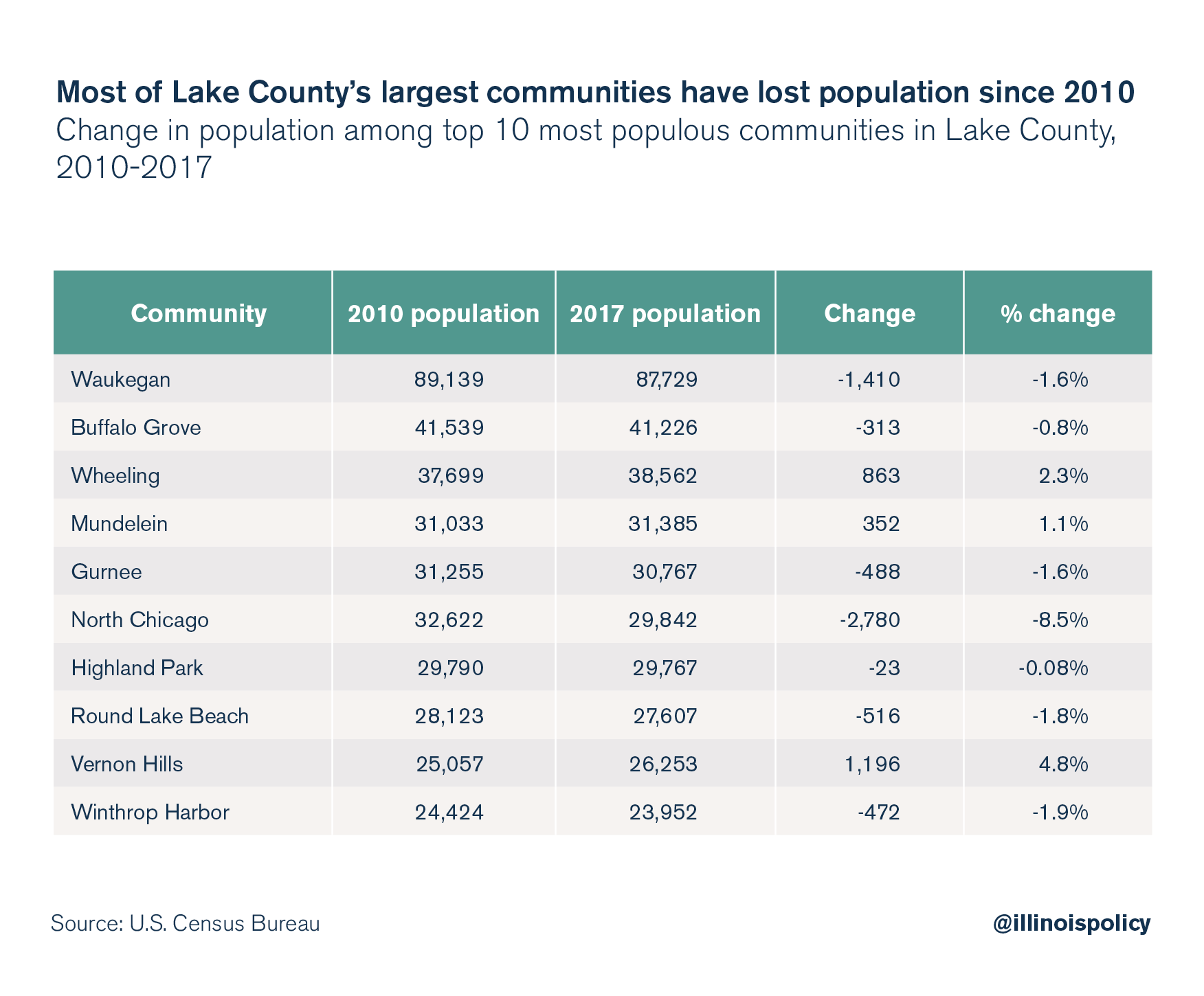

Of Lake County’s 10 largest cities and villages, seven have seen their population shrink since 2010, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The most severe drop came in the city of North Chicago, losing 8.5 percent of its population from 2010 to 2017.

It was joined by Winthrop Harbor (a 1.9 percent decline), Round Lake Beach (-1.8 percent), Waukegan (-1.6 percent), Gurnee (-1.6 percent) and Buffalo Grove (-0.8 percent). Highland Park also saw a dip of less than 0.1 percent.

Meanwhile, Mundelein, Wheeling and Vernon Hills each saw population growth from 2010 to 2017.

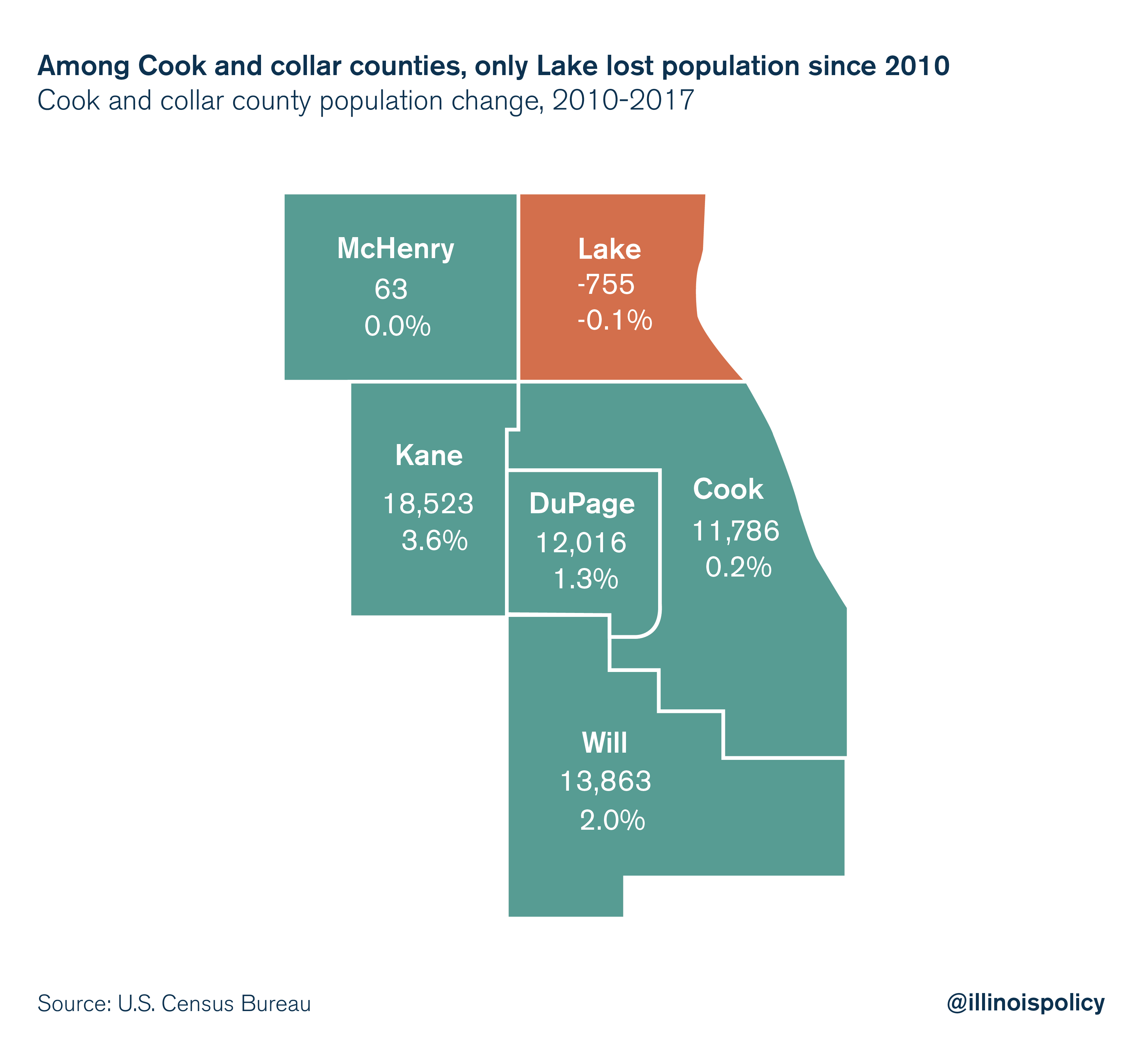

Among Cook and the collar counties, only Lake County saw population loss from 2010 to 2017, with a slight decline of 755 residents.

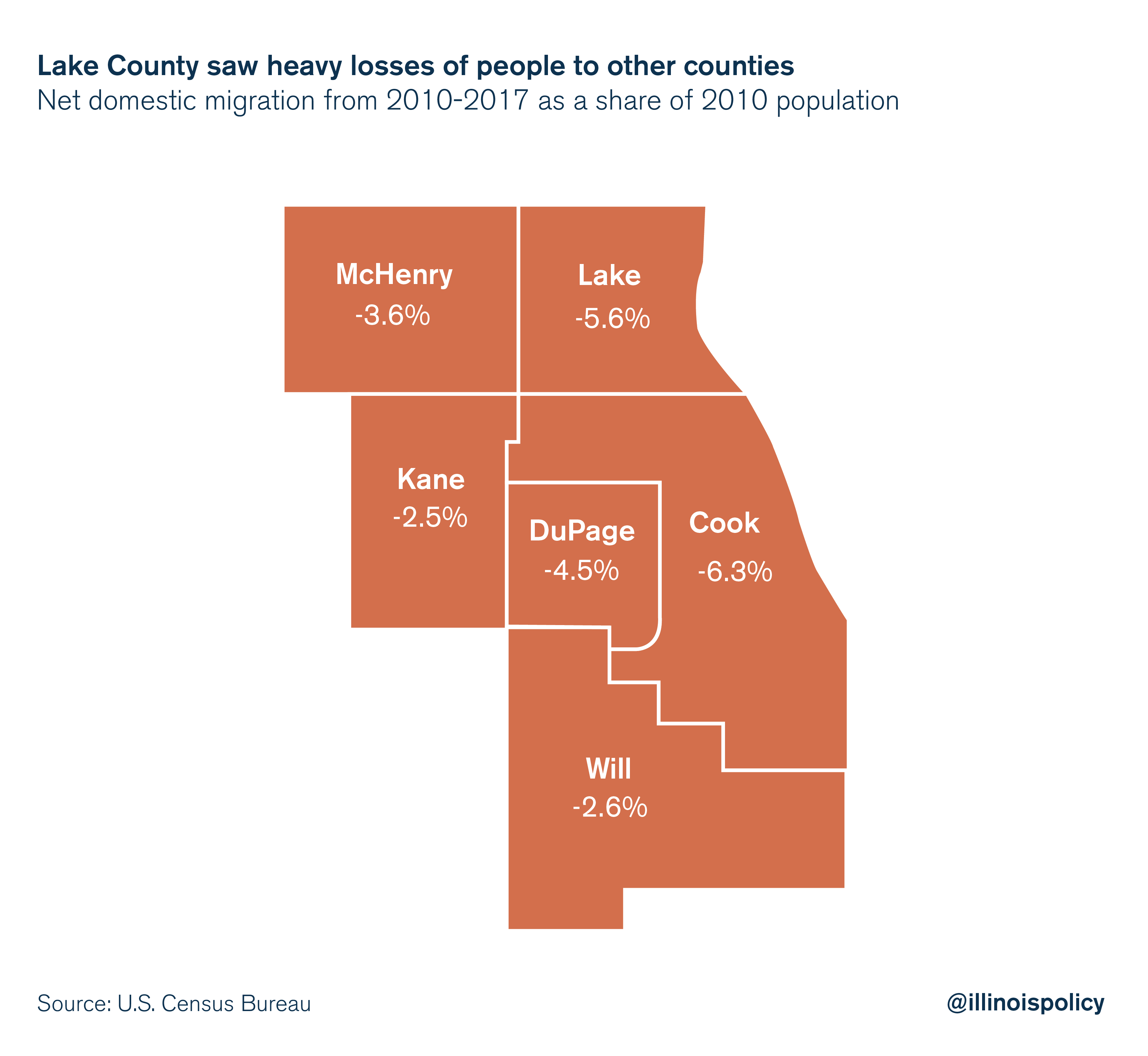

Lake’s population loss was driven primarily by a net outflow of more than 39,100 people to other U.S. counties from 2010 to 2017, amounting to 5.6 percent of its 2010 population. No other collar county saw such severe losses to domestic migration over that time.

It’s clear the northern collar county has found difficulty keeping and attracting residents. One challenge Lake County communities must contend with in fighting for investment is an extraordinarily high property tax burden. In 2017, the average effective property tax rate in Lake County was 2.7 percent, or $8,990 for a typical single-family home, compared with a national average of 1.17 percent, according to ATTOM Data Solutions.

Families are often willing to pay higher property taxes for outstanding public services. But Lake County residents are increasingly seeing their higher property tax bills pay for pensions, rather than services that increase home values.

The village of Mundelein hiked its property tax levy by 5 percent in December 2017 to meet rising police and fire pension costs. Shrinking Waukegan and North Chicago both face severely underwater pension funds. Waukegan’s police and fire pension funds have less than 50 cents on hand for every dollar needed to pay out future benefits, while North Chicago has less than 40 cents on the dollar for its police and fire pensions. Leaders in both cities are being forced to consider property tax hikes or service cuts to cover the shortfall, despite declining tax bases.

Higher taxes and diminished services to pay for unsustainable pension promises are not encouraging signs for prospective Lake County residents and businesses. Easing the property tax pain in these communities should be a top priority among state lawmakers seeking to attract new investment.