Moody’s: Chicago pension-reform ruling means increased financial pressure, rapidly growing pension debt

The Illinois Supreme Court’s overturning of Chicago’s modest pension reform means Chicago faces higher pension contributions, rapidly growing pension debt and an increased risk of total insolvency for its pension funds.

The Illinois Supreme Court on March 24 struck down Chicago’s modest reforms of the city’s municipal and laborers pension systems. Now that the law has been struck down, Chicago is back to square one in terms of pension reform. Moody’s Investors Service predicts that in light of this decision, city-worker pension costs will rise significantly over the next 15 years.

Had it not been struck down, Chicago’s pension-reform law would have required taxpayers to put more into the pension funds going forward, and would have slightly increased city workers’ contributions to their own retirements. It would have also reduced cost-of-living adjustments and instituted a funding guarantee for the two pension systems.

The plan was far from ideal, but it did reduce some of the long-term financial pressure on the city and opened the door to future reforms.

Thanks to an analysis by Moody’s Investors Service, Chicago residents know how much worse the city’s pension crisis is going to get in the wake of the Illinois Supreme Court’s ruling.

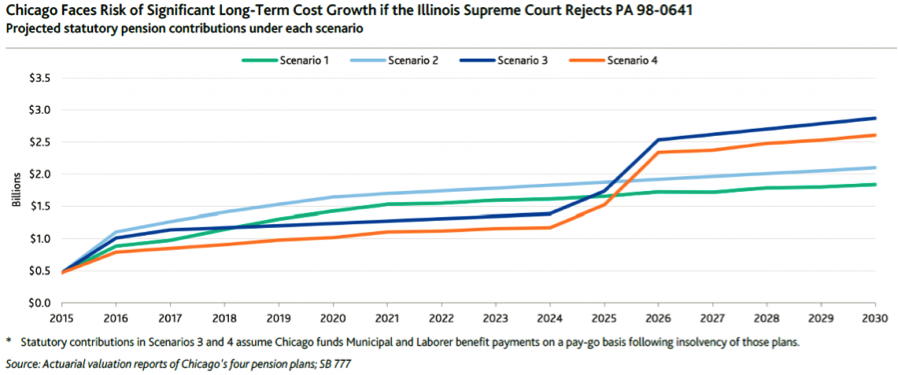

In November 2015, Moody’s released a special report that analyzed four different pension scenarios for Chicago based on two separate developments:

- Whether Gov. Bruce Rauner would sign a bill allowing Chicago to extend its timeline to repay police and fire pensions by 15 years, reducing the financial burden on the city in the short term. If the governor doesn’t sign the bill, city contributions to the police and fire pension funds will increase by $500 million in 2016, and will continue to increase year after year.

- Whether the Illinois Supreme Court would ultimately uphold the city’s reforms to the municipal and laborers pension systems – which increased city contributions to the funds in the short term, but included benefit reforms that cut pension costs in the long term.

Now that the Supreme Court has struck down the city’s pension-reform law, the scenarios put forth by Moody’s are narrowed down to whether Rauner signs the police and fire bill.

Unfortunately for city taxpayers, the Moody’s report showed that regardless of the governor’s action, taxpayer contributions to city-worker pension systems are going to rise significantly over the next 15 years. Chicago’s long-term government-worker pension situation will remain a significant cause for concern and a threat to the city’s credit-worthiness.

Under either scenario (scenario 3 and scenario 4 in the graphic below), Chicago’s contributions to its four government-worker pension funds will jump to around $1 billion in 2016 from $500 million in 2015. By 2030, the city’s contributions will be five to six times higher than its original 2015 payment.

The Moody’s report also warned that if the city’s reform bill was struck down, Chicago’s pension funds would suffer from an increased risk of “the possibility of asset depletion” – meaning the funds could go bankrupt.

Further, the report’s projection of government-worker pension contributions is actually conservative. It assumes unfunded liabilities won’t rise due to a drop in stock markets or if actuarial assumptions change. If those things happen, the city’s required contributions will grow even higher than the ratings agency projects.

Real, long-term solutions

Instead of passing massive tax hikes that only serve to burden residents, it’s time the city focused on passing real reforms that can help fix the pension crisis in the long run.

Positive reforms for the city include moving all new city employees into 401(k)-style plans, offering optional 401(k)-style plans to current workers and freezing city-employee salaries to shrink the growth in accrued pension benefits.

In addition, Chicago should end teacher pension “pickups” – under which Chicago Public Schools pays for a majority of its teachers’ required employee pension contributions as a special benefit.

And if all these reforms ultimately prove unsuccessful in slowing the growth of Chicago’s government-worker pension liabilities, the city should be given the option to declare bankruptcy.