Moline proposes hiking city’s already-high property taxes

City officials suggest Moline will face a budget deficit without a property tax hike – which would only worsen the property tax plight of area homeowners.

Update: The Moline City Council voted Oct. 23 to increase the city’s property tax levy for 2019, along with cuts to salaries, equipment upgrades and cuts to spending on a comprehensive plan. A full budget will be voted on in an upcoming meeting.

Despite countywide property taxes higher than the state average – and more than double the national average – Moline officials are considering a property tax hike as part of the city’s fiscal year 2019 budget.

The proposed budget presented to city aldermen Oct. 16 included a 2.5 percent property tax hike. Moline City Administrator Doug Maxeiner said the city has suffered “anemic” revenue growth and would face a $338,215 budget deficit without a property tax hike.

But with property taxes already squeezing Moline and other Rock Island County homeowners, another tax hike isn’t likely to put the city on a better path in the long term. In fact, it may risk driving away more of its tax base.

The average property tax bill for a single-family homeowner in Rock Island County was $2,855 in 2017, according to ATTOM Data Solutions, a property data company. With the average home value estimated at just under $111,700, that bill brings the average effective property tax rate up to 2.56 percent. In contrast, the state average in 2017 was 2.22 percent, while the national average was just 1.17 percent.

With the median household income in Rock Island County at $50,200 – slightly lower than the statewide median of $59,200 – many families in the region are deciding that the area’s high property taxes are simply unaffordable.

Taxes are Illinoisans’ No. 1 reason for leaving the state. And the state’s Quad Cities region appears to be no exception.

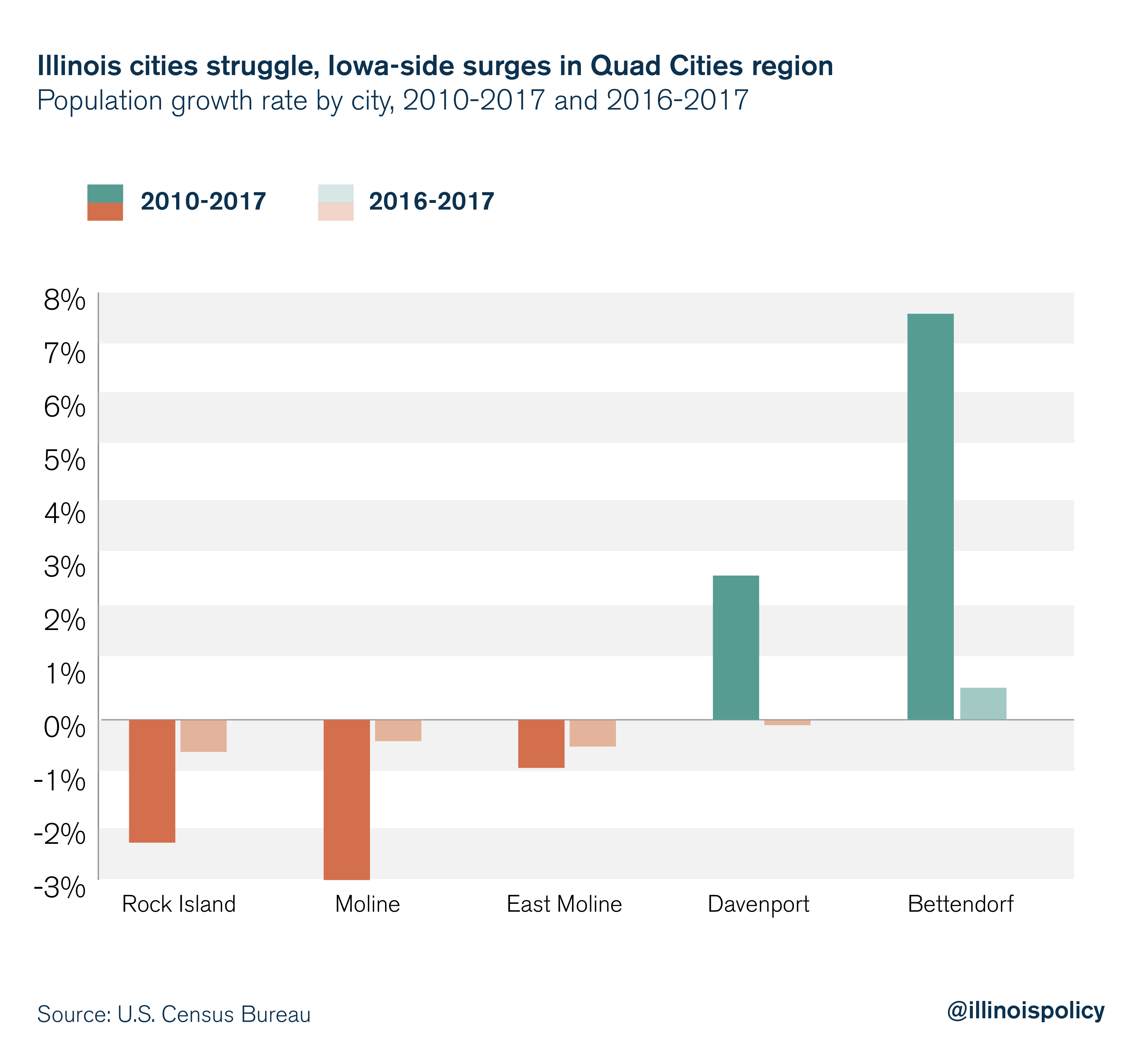

The Quad Cities include the cities of Rock Island, Moline and East Moline on the Illinois side of the Mississippi River, and Davenport on the Iowa side. Bettendorf, Iowa is also included in the greater metropolitan region. The Illinois side of the river has been continually shrinking in population, even while the Iowa side has grown. From 2010 to 2017, Davenport and Bettendorf saw their populations grow by nearly 5,200 people combined, while Rock Island, Moline and East Moline lost nearly 2,400 residents combined. If these trends continue, Bettendorf will overtake Rock Island as the third-largest city in the region by 2022.

Rock Island County’s population losses are driven in large part by its outflow of residents moving to other counties surpassing its inflow of new residents. And Scott County – on the Iowa side of the Quad Cities – is likely an attractive destination for overtaxed Illinoisans. Scott County had an average effective property tax rate of just 1.64 percent in 2017, presenting neighboring Illinoisans with a clear route to more affordable housing.

Moline officials should work toward reforms that lower costs, rather than increasing residents’ already-high tax burden. Lawmakers in Springfield must also recognize that Illinoisans are in need of relief, and take necessary steps toward reining in the cost drivers behind property tax hikes.

Most importantly, Springfield must address the state’s out-of-control pension costs. If lawmakers are serious about property tax reform, they must push for a constitutional amendment that allows changes to future, unearned pension benefits.

Until state and local lawmakers advance measures that provide homeowners with the relief they need, Moline’s shrinking population will continue to endure painful tax hikes.