Manufacturer moves out of Madigan’s backyard, cites unfriendly business climate

Illinois’ middle class is crumbling under the weight of the state’s political and legal classes.

Illinois’ manufacturing meltdown is showing no signs of stopping.

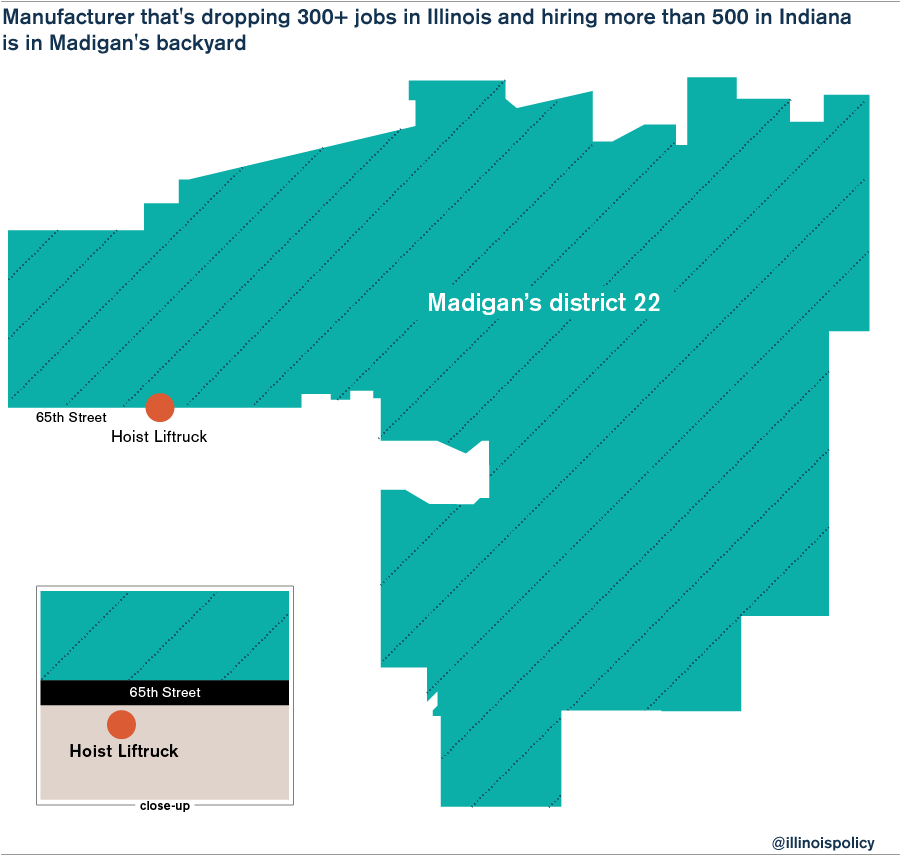

Hoist Liftruck, a manufacturer of industrial forklifts, has announced plans to move more than 300 manufacturing jobs from Bedford Park, Illinois, to East Chicago, Indiana. The firm plans to add another 200 workers over the next few years. Hoist is the previously unnamed manufacturer that made headlines a month ago when it announced the plan to create 510 jobs paying $55,000 per year in Indiana.

“I love this city,” said Marty Flaska, president and CEO of Hoist Liftruck. “But if we can keep an extra $2 million [per year] in our family businesses by moving 15 miles away, why wouldn’t we?” The manufacturer is currently located in Bedford Park, on the south side of 65th Street. House Speaker Mike Madigan’s legislative district is just across the street.

The reason for Flaska’s exit is clear.

“If I didn’t have the workers’ compensation issue and the [property-tax] issue, I probably never would have even considered moving. Why would I?”

He’s speaking of a broken system that has festered in Illinois for decades under Madigan’s leadership. A system that has borne rotten fruit in the form of Illinois manufacturers leaving the state in droves, taking middle-class manufacturing jobs with them. Blue-collar families have seen the following in the last 30 days alone:

- A July 29 announcement by Mondelez International that it will lay off 600 manufacturing workers from its South Side facilities

- A July 24 announcement by Mitsubishi Motors that it will close down production facilities in Normal, Illinois, jeopardizing 918 automotive manufacturing jobs

- A July 16 announcement by General Mills that it will shut down its manufacturing plant in West Chicago, Illinois, laying off 500 workers

- A July 15 announcement by energy processor Bunge North America that it will shut down its plant in Bradley, Illinois, laying off 210 workers

- A July 14 announcement by machine-maker DE-STA-CO that it will move 100 manufacturing jobs from Wheeling, Illinois, to Nashville, Tennessee

Some of these companies, including Hoist Liftruck, have received subsidies or tax credits from other states to lure them away from Illinois, but Flaska says it’s not that simple.

“Forget about incentive money, when you look at the pure cost for me to do business in Illinois, the choice is clear.”

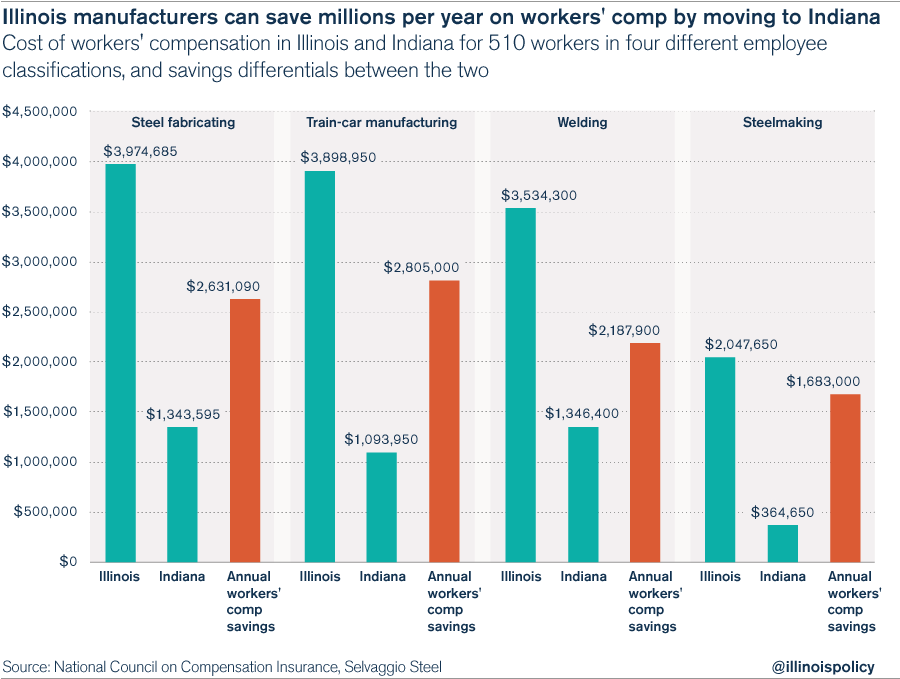

A look at the difference in insurance premiums for workers’ compensation across state lines proves Flaska’s point. A company of his size pays millions more each year for insurance than a similar business in Indiana.

In fact, Flaska decided to self-insure after paying millions to settle dubious workers’ compensation claims out of court. He wanted arbitration on each claim rather than being forced to settle for less than the high cost of going to a judge.

“Most attorneys that practice workers’ comp law in Cook County know we’re going to fight,” Flaska said. “But I still spend between $10,000 and $15,000 per case – three cases a month minimum – to fight.”

Flaska is not alone.

Mark Selvaggio, president of Springfield’s Selvaggio Steel, said his small manufacturing firm would save $60,000 annually on workers’ compensation alone if they were located in Indiana. He estimates he could hire six more workers if Illinois’ business climate looked like Indiana’s.

While the state’s costly workers’ compensation regulations may seem pro-worker, that’s not really the case, said Don Haider, a professor at Northwestern’s Kellogg School of Management, especially when manufacturing jobs are drying up as a result.

“Workers’ compensation [in Illinois] is one of those things where the benefits flow not just for purposes of industrial safety and protection of the workers,” he said.

“It goes to the real beneficiaries, who by and large are the lawyers and the tort industry. They’re the beneficiaries of this business irritant.”

As major employers leave Illinois to escape a hostile business climate, the state’s middle class is crumbling under the weight of rent-seeking political and legal classes. This is seen not only in the workers’ compensation climate, but also the property-tax climate, where businesses must pay lofty attorneys fees to stem the tide of rising property valuations.

This is the kind of law in which Madigan’s law firm specializes.

“Illinois should do what other states have done,” Flaska said. “Indiana’s done it. Pass a state law that says [property] taxes can’t exceed X percent.”

Thankfully, common-sense reforms establishing clear standards within Illinois’ workers’ compensation system and freezing the nation’s second-highest property taxes are on the bargaining table in Springfield. Gov. Bruce Rauner has placed them there for a reason – Illinois must stop its exodus of people and businesses if the state is to forge a stable fiscal future.

But Madigan refuses to budge, even when the effects of inaction are being felt a few miles down the road from his district office.