Making Illinois smart on crime: How to improve felony theft outcomes

Raising the felony theft threshold won't lead to an increase in overall property crime or larceny rates.

If you steal an iPhone in Texas, you’ll be charged with a misdemeanor and receive a sentence of up to a year in county jail; but if you steal an iPhone in Illinois, you’ll be charged with a felony and face up to five years in prison.

The Illinois State Commission on Criminal Justice and Sentencing Reform recommended raising the felony theft threshold to $2,000 from $500 in a Jan. 10 report. This was the second report the commission released with suggestions on how to reduce Illinois’ prison population 25 percent by 2025, per Gov. Bruce Rauner’s executive order.

House Bill 3337, which was introduced Feb. 22, would make good on the commission’s recommendation by increasing the felony theft threshold to $2,000.

Why Illinois needs to make good on prison population reduction

Illinois’ criminal justice system is failing people – crime victims, taxpayers and ex-offenders alike. The state spent $1.4 billion on the Illinois Department of Corrections, or IDOC, in 2014, not including pay and benefits for all workers. The results don’t match the investment: Nearly half of ex-offenders return to prison within three years – and each instance of recidivism costs nearly $120,000.

Cycling in and out isn’t just costly in the financial sense – it also squanders human potential. The public has a vested interest in ensuring that offenders are rehabilitated, because 97 percent of people residing in Illinois prisons will return to their neighborhoods. When nearly half of ex-offenders return to prison just three years after release, it’s clear the system isn’t working.

Raising felony theft threshold doesn’t lead to increased theft

Since the commission’s report was released, critics have voiced concerns about sending the wrong message.

“If you take away the punishment side of it, and you’re just going to slap them on the hand, they’re more likely to come back, and there’s more people that are going to try it for the first time,” Quincy Menards Assistant General Manager Scott Warner said in an interview with WGEM TV.

But increasing felony theft thresholds doesn’t equate to an increase in theft.

The Pew Charitable Trusts examined crime trends in the 28 states that raised their felony theft thresholds between 2001 and 2011, and issued three main findings:

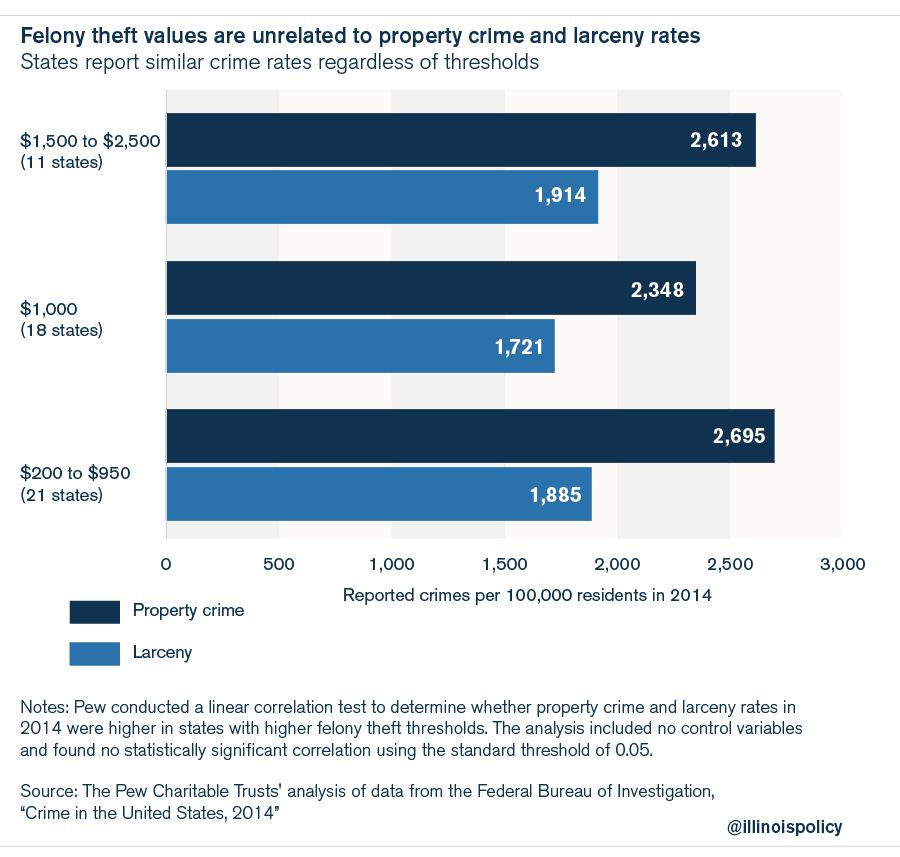

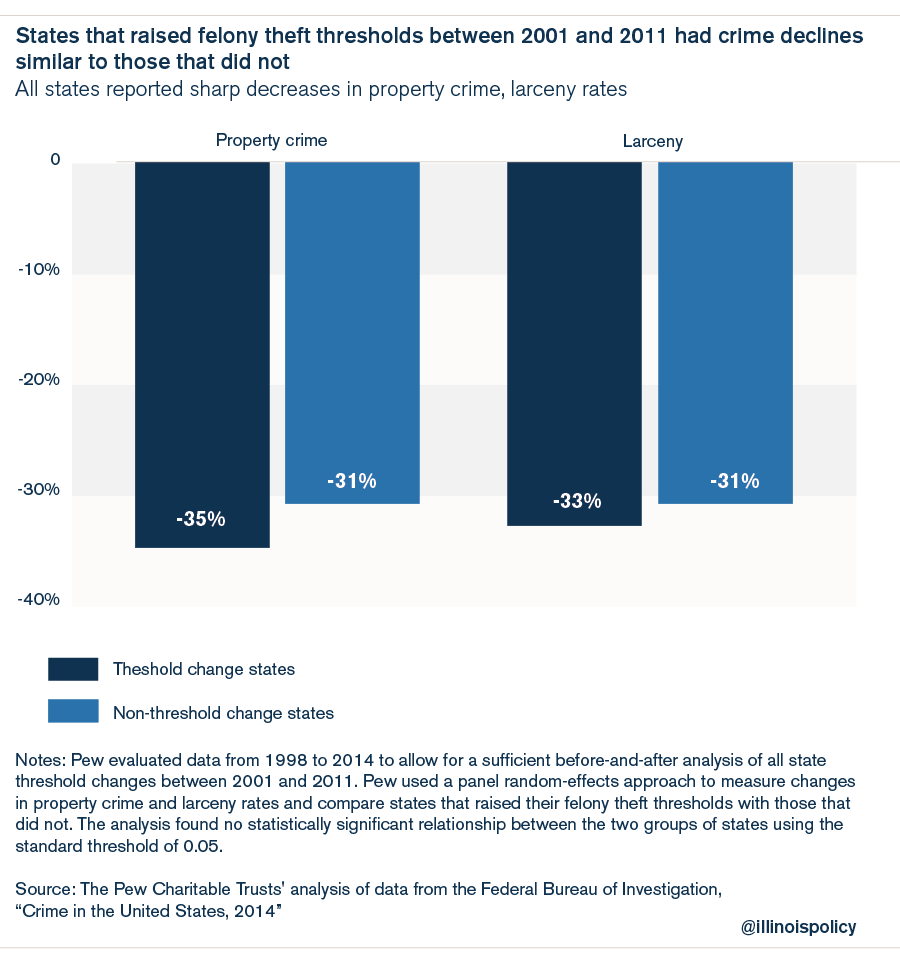

- Raising the felony theft threshold has no impact on overall property crime or larceny rates.

- States that increased their thresholds reported roughly the same average decrease in crime as the 22 states that did not change their theft laws.

- The amount of a state’s felony theft threshold – whether it is $500, $1,000, $2,000, or more – is not correlated with its property crime and larceny rates.

Compared to Illinois’ $500 trigger, 29 other states have felony theft thresholds that are twice as high or even greater, including states like Texas and Wisconsin, where theft below $2,500 is generally a misdemeanor.

For effective reform, take victims into consideration

Not only does Illinois send nonviolent offenders to prison for longer than necessary, but Illinois’ system for dealing with theft crimes also means that even if an offender is punished, victims are not made whole.

In addition to adjusting theft thresholds, a truly effective way to deal with theft is to encourage additional, alternative reforms such as restorative justice, which compensates victims for their losses.

Texas provides a great example for this type of approach, and Illinois should follow suit. The Lone Star State offers a program that allows offenders and victims to work together to come up with appropriate steps to restore any losses or damages, instead of throwing the offender into prison where he or she will have no job and thus no means of repaying his or her debt. Offenders who go through the Texas program have a three-year recidivism rate – meaning, the rate at which offenders return to prison within three years of release – of 18.6 percent. For reference, Illinois’ three-year recidivism rate is 50 percent.

Smart reform addresses not just offenders, but victims as well, and works toward better outcomes for both parties. That starts with ensuring people aren’t sent to prison unnecessarily or for overly long terms, and continues with providing avenues for victims and offenders to work together to make amends for property losses.