Madigan-Pritzker progressive tax: 2019’s worst policy idea for Illinois’ middle class

Other states’ experiences show progressive taxes creep beyond the rich and into the pockets of the middle class.

Are Gov.-elect J.B. Pritzker and House Speaker Mike Madigan poised to align on a progressive income tax hike?

The history of both politicians suggest as much. Dismantling Illinois’ constitutionally protected flat income tax was a key pillar of Pritzker’s campaign. And House Speaker Mike Madigan has a history of lobbying for a “millionaire tax,” as well as other progressive income tax efforts.

But beyond politics, the history of progressive income taxes in other states should be a major cause for concern for average Illinois families.

Why? Other states’ experiences show that while sold as a tax on the rich, progressive income taxes instead creep into the pockets of the middle class.

It’s a risk that residents shouldering one of the most extreme tax burdens in the nation can’t afford to take.

Cash grab

Before analyzing the history of the progressive income tax across the U.S., it’s important to understand what a progressive tax in Illinois is really about: more revenue to fund decades of irresponsible budgeting.

Illinois is already facing a $2.8 billion deficit, which is projected to swell to $3.4 billion in fiscal year 2021 – the first full year state government could collect revenues from a progressive income tax – and Pritzker’s campaign promises carry a tab of $13 billion to $18 billion in additional annual expenses.

To make room in the budget for spending on the governor-elect’s priorities, lawmakers should address the main cost-drivers and structural flaws in Illinois state government that have led to 18 consecutive years without a balanced budget.

Resorting to tax hikes via a progressive income tax and using accounting gimmicks to “balance” the budget will only threaten the state’s economic health and ultimately require reaching into the wallets of the middle class.

History lesson: Progressive income taxes start by hitting the rich and end up soaking the middle class

Just like Illinois’ flirtation with a progressive income tax, the federal income tax was sold as a small tax that would only affect the rich, with the vast majority of Americans being excluded from taxation.

This was initially true.

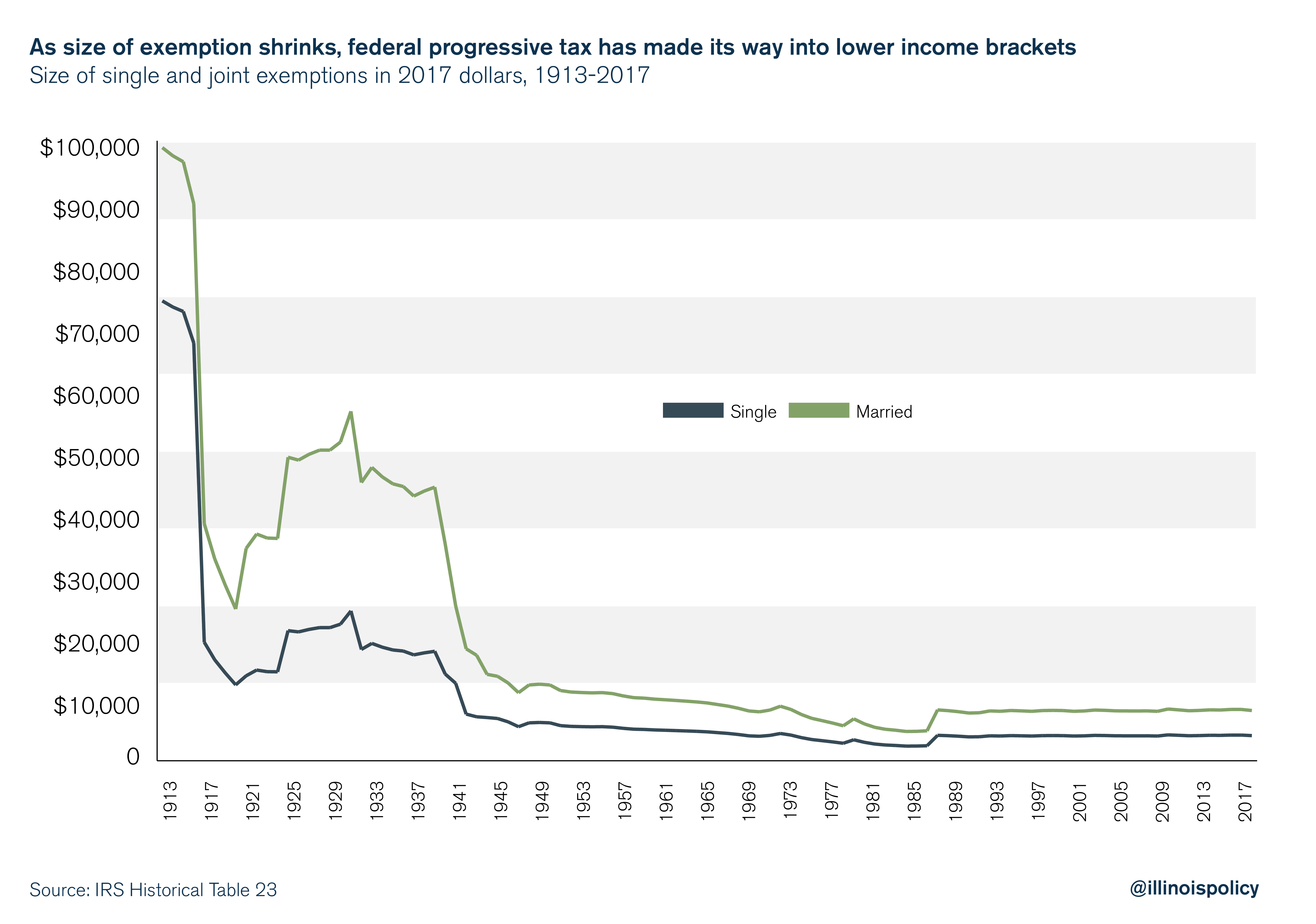

When lawmakers passed the Revenue Act of 1913, the first $3,000 of income for single filers and $4,000 of income for married filers was exempt from taxation. That’s the equivalent of $74,200 for single filers and $98,900 for married filers after adjusting for inflation.

But this didn’t last long. By 1918, the exempted incomes fell to $1,000 and $2,000 respectively, or $16,300 and $32,600 in 2017 dollars. While the exempted amounts were raised during the next couple of decades, the exemption amount has been relatively stable in the post-war period, with nearly all income subject to taxation.

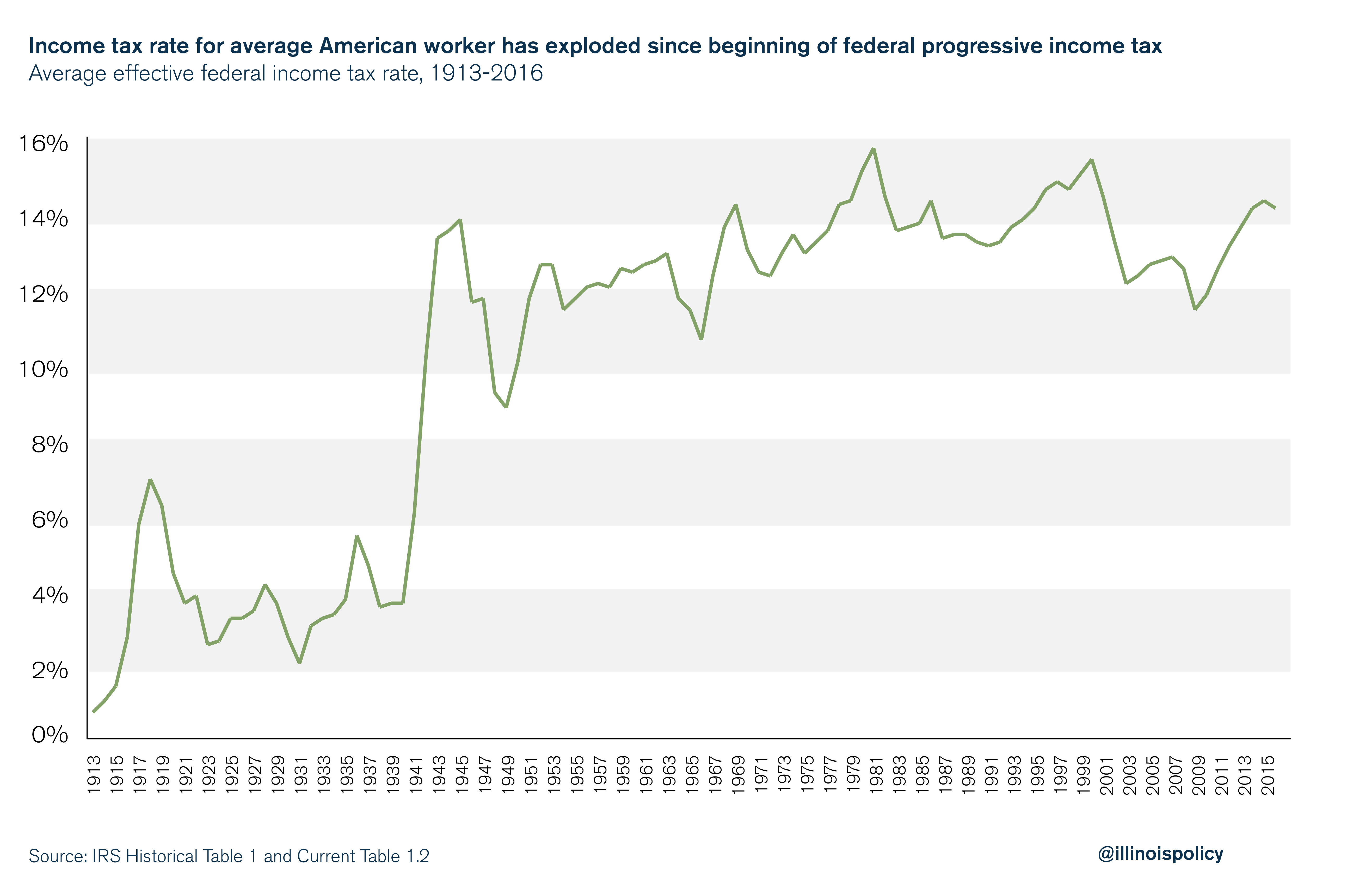

The low tax rates that applied to taxable income were also quickly raised. The initial tax rates were between 1 percent and 7 percent, with the average effective tax rate (after factoring in exemptions and deductions) being 0.7 percent.

By 1918, tax rates ranged from 6 percent to 77 percent, with the average effective rate clocking in at 6.88 percent – nearly 10 times higher than the original tax and affecting a much greater share of the population.

As with the amount of income exempt from taxation, tax rates declined for a couple of decades after their initial spike. However, tax rates then rose significantly and have remained relatively stable in the post-war period.

Today, the average effective federal tax rate is more than 14 percent and affects the majority of working Americans. This reality is a long way from the idea that was originally sold to taxpayers.

State-level income taxes introduced under the same false premise

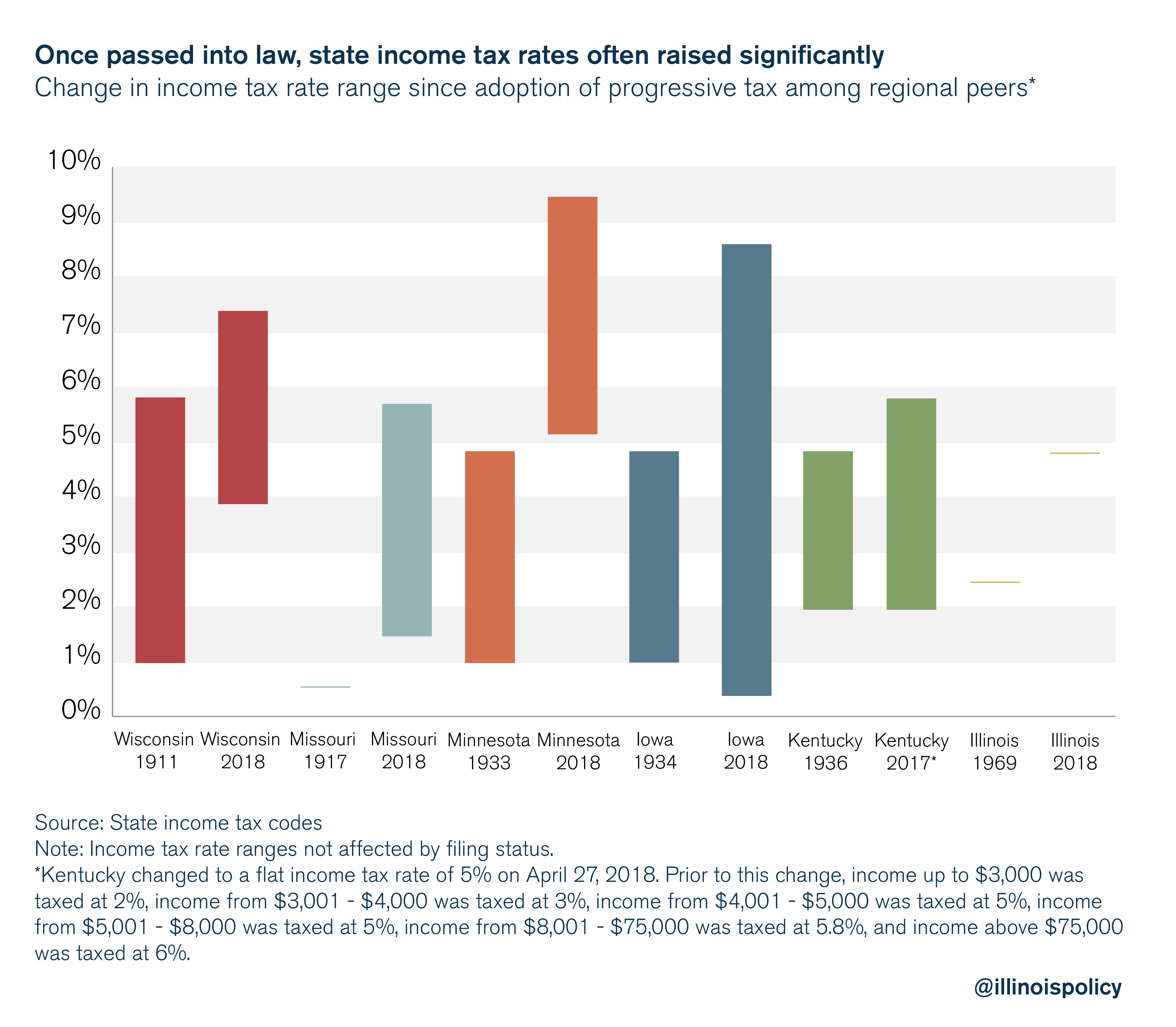

State lawmakers have also passed income taxes under the guise that the income tax rates would be low and primarily affect high-income earners. This promise was rarely kept.

After the introduction of income taxes, states tend to significantly raise both the highest and lowest marginal tax rates, meaning many citizens – including the middle class – experience income tax hikes.

While historical data from the early years of state income taxes is hard to come by, the initial income tax rate ranges in nearby states that have adopted progressive tax structures show they are inevitably expanded once implemented.

How a Madigan-Pritzker progressive tax would harm Illinoisans

Illinois’ multibillion-dollar budget shortfall requires Pritzker and state lawmakers to reduce spending or raise taxes. While Pritzker may attempt to deliver on his campaign promise of instituting a progressive income tax, he has not released his preferred rate structure.

Madigan’s recent proposal for a millionaire tax, however, shows the limits of such progressive tax measures.

Although the millionaire tax failed to pass the General Assembly in 2014, 2015 and 2016 a similar proposal could find its way to the floor once more in 2019.

Madigan’s 2016 proposal would have levied a 3 percent surtax on income in excess of $1 million.

But this special tax – which would fall on approximately 0.3 percent of all Illinoisans – would not generate nearly enough revenue to even close the projected budget shortfall, much less pay for new spending.

The 3 percent Madigan millionaire tax would bring in an estimated $1.2 billion. Even when factoring in high-end estimates for tax revenues from legalizing recreational marijuana, this Madigan millionaire tax would cover less than half the projected deficit in fiscal year 2021, when it would be allowed to take effect.

Keep in mind that this is the best-case scenario, as traditional revenue estimation (often called static scoring) does not factor in the effects of tax hikes on income earners’ working and investing behavior.

The incentive effects of a millionaire tax

While an extra tax on income over $1 million may have political appeal for some Illinoisans, it’s important to recognize the effects of such a tax on the vast majority of Illinois families who don’t take home more than $1 million. Namely, high-income earners are much more mobile. And when they leave, the middle class is stuck with the bill.

Many economists have found that while all individuals are responsive to income taxes, high-income earners are significantly more responsive, while the middle class is the least responsive.

Individuals and businesses alike are likely to alter their financial portfolios, charitable donationsand investment decisions, reduce their labor supply, or just flee the state altogether to avoid increased tax burdens. Those who are most likely to alter their behavior in response to higher taxes are high-income earners. A millionaire tax would ultimately result in lower investment in the state, further hampering Illinois’ employment prospects which already lag the nation.

The high responsiveness of higher-income individuals to changes in the tax code indicate: 1) this form of taxation will not provide a long-term solution to Illinois’ fiscal insolvency, meaning annual budget shortfalls would persist despite a millionaire tax and; 2) to obtain the desired revenue, the increased tax rates would have to be expanded to middle class workers who are less responsive to taxation.

These results imply the optimal income tax system– the one that raises the most revenue with the least amount of harm to the economy – is similar to Illinois’ current flat tax system: progressive on average (as exemptions and deductions primarily benefit lower incomes and high-income earners already pay a higher effective tax rate) but not progressive at the margin.

A progressive income tax in Illinois would mean a middle-class tax hike

The millionaire tax proposal is no different than the false promises used to pass other progressive income taxes. The plan will inevitably fail to generate the anticipated revenue, and when revenues from a progressive income tax fall short, the door will already be open to expanding tax brackets and increasing tax rates on the middle class.

A millionaire tax won’t even be able to close the projected budget deficit, let alone finance the billions of dollars’ worth of additional spending that Pritzker promised during his campaign. Furthermore, the policy would exacerbate the gap in employment growth between Illinois and the rest of the nation.

To avoid middle-class tax hikes in the long term, Pritzker must instead pursue reforms allowing for more efficient, predictable and stable government spending.