Lightfoot looks to Springfield for more taxing power on high-end services, home sales

Chicago’s mayor wants permission from Springfield to impose a new tax on high-end professional services and raise taxes on pricier home sales, as the city faces down a $1 billion deficit.

Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot is aiming to address a worse-than-anticipated budget shortfall without another property tax hike – by securing new power over other new taxes.

The Illinois General Assembly reconvenes for veto session for three days in October and three days in November, during which Lightfoot hopes to persuade state lawmakers to allow Chicago to impose a new tax on high-end professional services, such as legal and accounting work, as well as raise taxes on home sales exceeding $1 million, according to the Chicago Sun-Times.

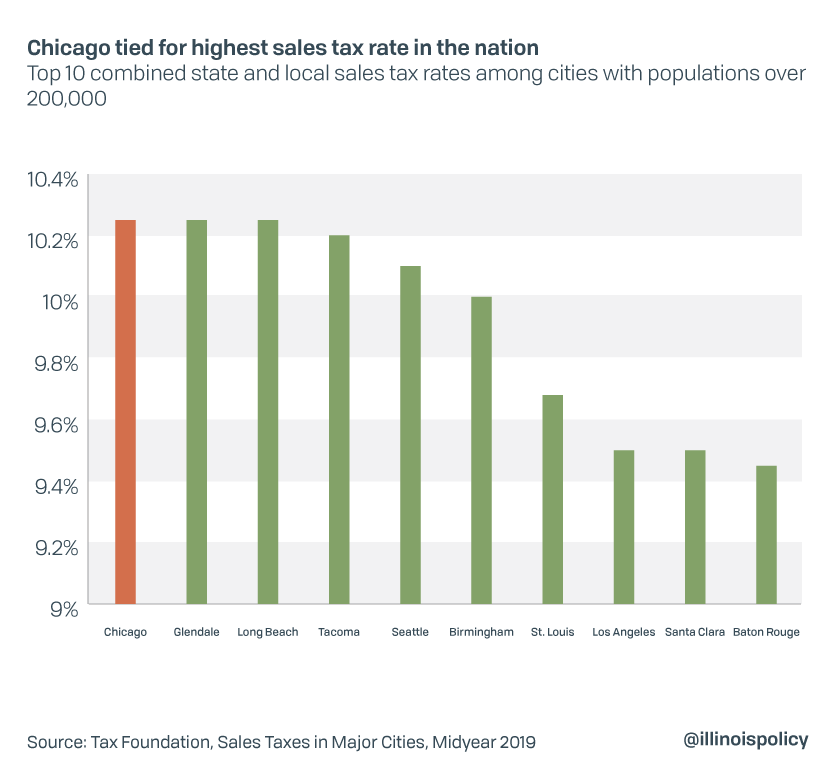

Lightfoot’s plea for more taxing power comes just a week after a Tax Foundation study found Chicago tied with Glendale and Long Beach, California, for highest combined state and local sales tax rate in the nation.

Lightfoot previously floated a high-end real estate transfer tax hike as a way to fund services for the homeless and create affordable housing. But an inherited deficit originally thought to be $740 million now stands at $1 billion and has commanded the mayor’s focus.

The city’s $1 billion deficit combines the structural deficit with pension contributions, debt service, a “parade of wrongful conviction lawsuits” and pending pay raises for public safety workers and teachers. The city is still negotiating with those unions, with the Chicago Teachers Union threatening to strike unless demands are met that total $479 million in the first year.

The mayor is presenting the tax proposals as a necessary alternative to hiking property taxes, which are already so high that additional hikes would be self-defeating by driving away residents. In 2015, former Mayor Rahm Emanuel passed the largest property tax hike in city history, in large part to pay for public safety pensions. Pension payments absorb most of Chicago’s property tax levy, with the rest going to debt service. Nearly all of the $321 million in water and sewer tax increases and 911 fees passed since 2015 go to pensions as well.

In Cook County as a whole, effective property tax rates have spiked by 22% since 2007, despite home values remaining 31% below their pre-recession peak.

Tumbling dice

In some respects, high taxes are already reaching a point of diminishing returns for the city. An Aug. 13 study commissioned by the Illinois Gambling Board found none of the five proposed sites for a Chicago casino were feasible, citing the “onerous tax and fee structure” imposed as part of the state’s recent gambling expansion.

The study noted the five South and West side locations would come with an effective tax rate of around 72%, and that a more central casino location downtown could be profitable. If not for the layers of high taxes and fees, the report found, the proposed Chicago casino would be the highest-grossing in the state.

The mayor’s goal for the Chicago casino, according to the Sun-Times, is to raise revenue to shore up Chicago’s police and fire pensions and close the city’s budget shortfall.

Lightfoot said she also plans to urge the General Assembly to revise the tax structure governing a Chicago casino when lawmakers return to Springfield for veto session, according to the Sun-Times. A Chicago casino would be taxed more than other Illinois casinos, with a one-third tax on the amount it pays to winners.

Illinois has a dismal track record betting on gaming revenue windfalls. In 2009, Illinois legalized video poker and slots to help fund a $31 billion infrastructure spending program. State lawmakers anticipated revenues of $1 billion by November 2013, but the expansion yielded less than $70 million by that time. Ultimately, the infrastructure program saddled taxpayers with $10 billion in debt .

Long-term solutions to long-term problems

In keeping with the rest of the state, the leading cause of Chicago’s fiscal problems is its worsening pension crisis. The city’s four pension funds are over $27 billion in debt and are only 26% funded. But like the budget deficit she inherited, Lightfoot has suggested the city’s pension debt could be even worse.

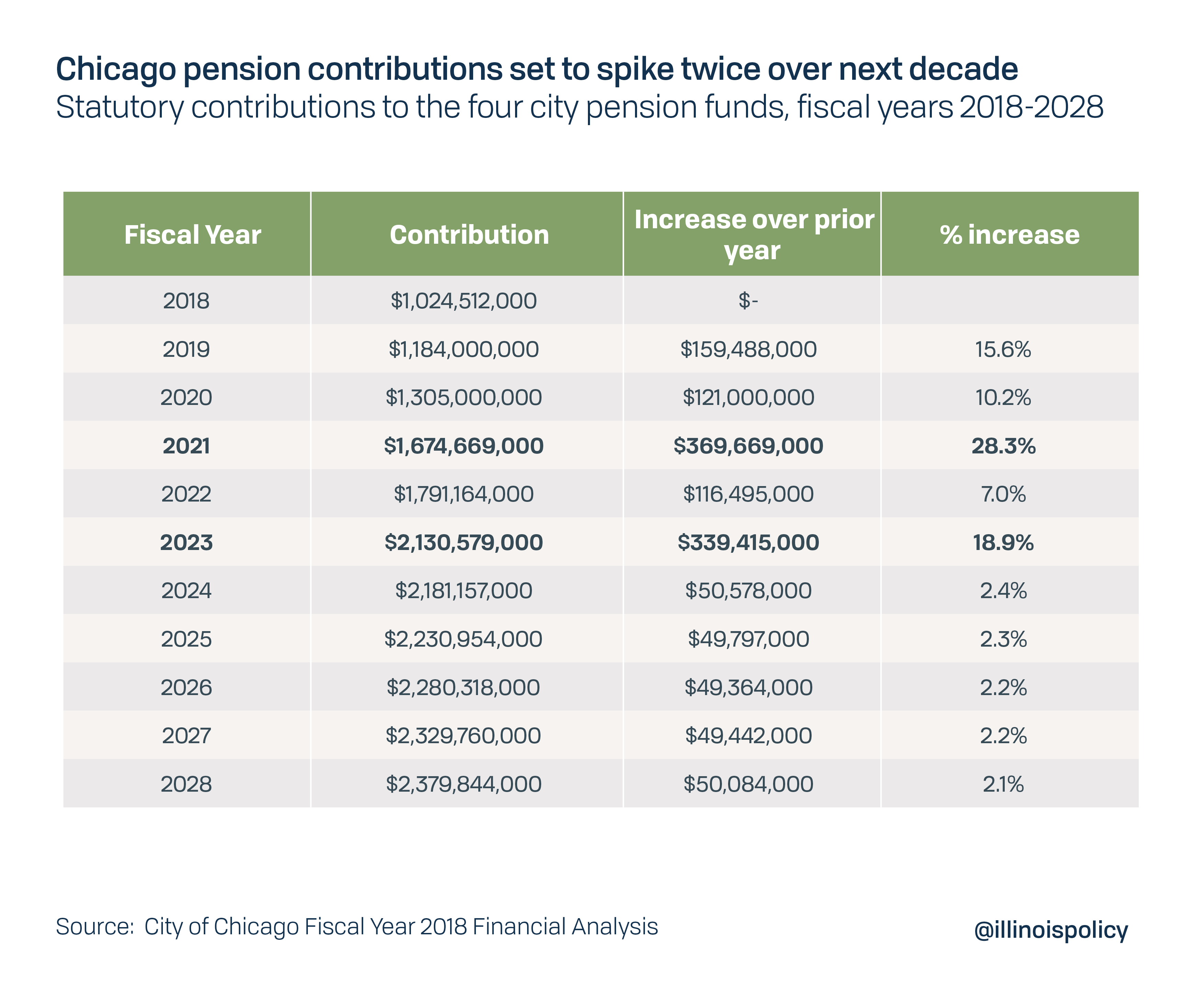

In the first year of Lightfoot’s term, Chicago’s required contribution to the city’s four pensions systems will increase to $1.3 billion – over $120 million from the previous year – before eventually reaching over $2.1 billion in 2023.

Chicago’s new mayor should not repeat the mistakes of her predecessor, who approved $864 million in tax hikes before making a public plea to Springfield for constitutional pension reform.

Lightfoot on the campaign trail declined to support the idea of changing the Illinois Constitution to reform pensions. But the unaffordable costs that have repeatedly driven her to seek aid from Springfield should make clear that amending the state constitution is the only long-term solution to stemming the growth of those costs.

That is why it is essential that Illinois pass a constitutional amendment that protects workers’ already-earned pension benefits but allows for changes in future benefit accruals, such as replacing automatic 3% annual raises with actual cost-of-living increases tied to inflation.

“I know how Chicago families, just like families in my [hometown], plan their lives and budgets around the pension promises we’ve made,” Lightfoot said in a statement on her campaign website.

Looming insolvency threatens to rob future retirees of those promises; constitutional reform is the only way to keep them.