Lightfoot budget includes automatic property tax hikes, gas tax hike

A typical Chicago homeowner faces up to $255 in potential property tax increases to cover city and school deficits. City income taxes could be next, if the ‘fair tax’ were to pass.

Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot wants property taxes to automatically increase with inflation and to impose a 3-cent gas tax hike to deal with a $1.2 billion deficit.

Lightfoot announced her proposed 2021 budget and gave the mayor’s annual budget address to the city council Oct. 21. She gave city residents suffering from the economic fallout of COVID-19 more budget gimmicks and more taxes to fill most of the city’s massive budget gap.

While the mayor in passing acknowledged the need for pension reform, she offered no specifics. She missed the chance to endorse the only real solution to Illinois’ pension crisis, a constitutional amendment allowing for reductions in future benefit growth.

The mayor’s proposals include:

Property tax hikes

The city estimates a homeowner with $250,000 in property value will pay an average of $56 more, slightly less than the percentage increase in the total levy. But both new construction and changes in assessment methodology could shift more of the property tax burden to businesses next year. The $93.9 million hike includes $42.5 million to fully fund pension contributions, as required by state law, $35.4 million to keep the city property tax levy even with inflation and $16 million from new property construction.

Lightfoot also proposed tying future property tax increases to inflation, meaning the amount of property taxes the city demands from property owners will increase each year. While the city council would still have to approve the increases as part of the annual budget process, tying property taxes to increases in the consumer price index could institutionalize automatic increases and reduce discussion of alternatives. Future mayors and alderman will have less incentive to find ways to control spending and find efficiencies if the budget process always assumes property tax hikes.

Gas tax hike

A bill signed by Gov. JB Pritzker in 2019 that doubled the state gas tax gave Chicago the option of raising its local gas tax by 3 cents to a total of 8 cents per gallon. The mayor’s budget exercises that option and is expected to raise $10 million.

Personnel reductions

Personnel reductions would save a total of $106.3 million through 350 layoffs and 1,912 vacancies left unfilled. They mayor is also asking all non-union employees to take five unpaid furlough days.

Budget gimmicks

While the plan achieves balance on paper, many of the savings ideas reportedly under consideration are gimmicks the city has historically used to claim budgetary balance while running end-of-year operating deficits each year since 2003. For example, the city hopes to find $262.6 million from unspecified “improved fiscal management.” It relied on $141 million in projected savings from the same line item for the fiscal year 2020 budget, which will end the year nearly $800 million in the red. The city says the deficit is from revenue losses related to the COVID-19 downturn.

The mayor will also be relying on transfers from other governmental funds, including a $30 million withdrawal from the city’s rainy-day fund and $304 million from tax increment financing districts, which are typically earmarked for economic development unless declared “surplus” by the mayor.

Debt refinancing

Lightfoot plans to swap old debt for new debt with lower interest rates by selling the rights to future city sales tax revenues to secure bonds. This debt refinancing is supposed to save $450 million in 2020, to help close the current year’s $800 million deficit, and $501 million in 2021, to close next year’s $1.2 billion gap. The city would front-load savings from the refinancing for budgetary relief. The city relied on $200 million in refinancing for the unbalanced 2020 budget using the same method.

Debt refinancing is a short-term revenue measure that does not help close the structural deficit. The city can only rely on debt refinancing so long as private bond buyers remain willing to purchase city debts. Crain’s Chicago Business reports an increase in city borrowing costs despite a generally low interest rate environment, with recent bonds carrying interest rates between 6.75% and 7.25%. Increased interest rates indicate investors view Chicago bonds as increasingly risky given its deteriorating financial condition.

Chicagoans staring down large property tax hikes

Lightfoot inherited among the worst city finances in the nation, with the city of Chicago already rated “junk” by credit ratings agency Moody’s Investors Service. Economic fallout related to COVID-19 has made the city’s budget problems even worse, exposing taxpayers to the threat of property tax hikes and other local tax increases.

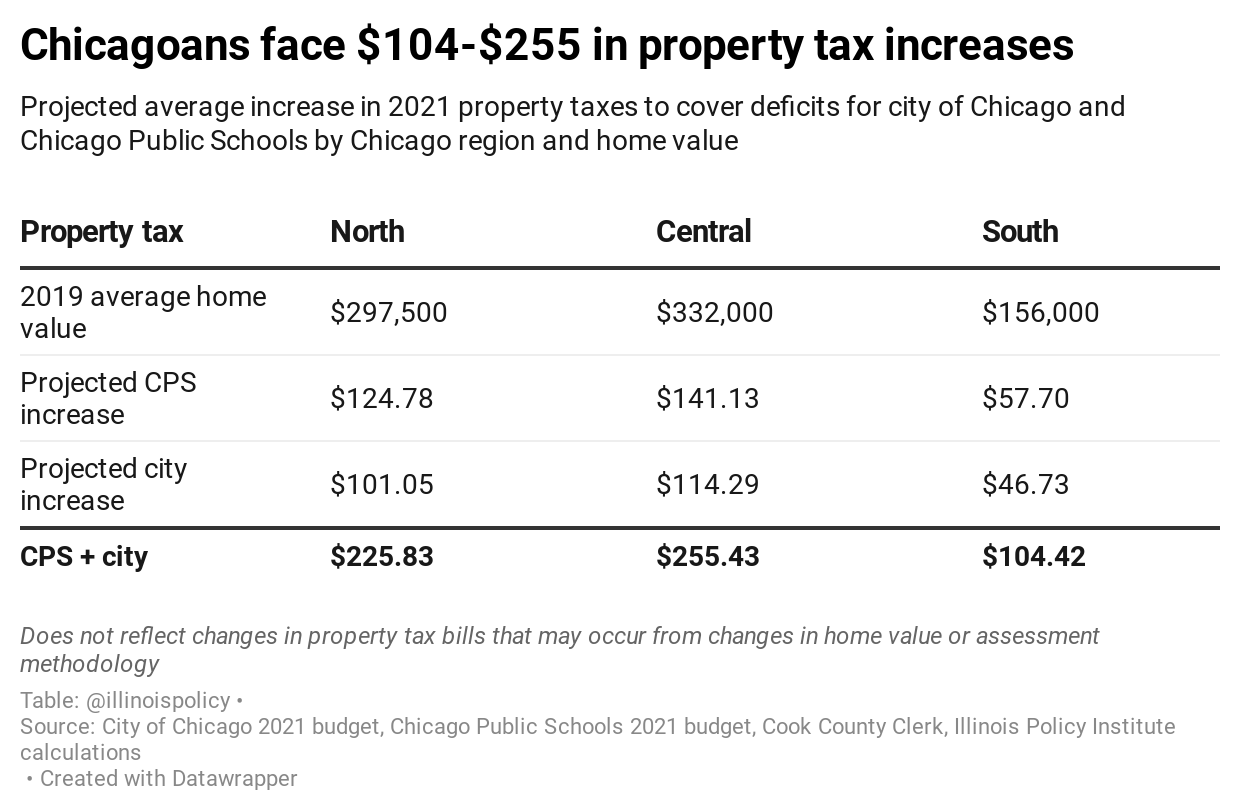

That could be devastating to Chicago taxpayers struggling with the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression. According to analysis from the Illinois Policy Institute, a typical homeowner will already be asked to pay between $104 and $255 in higher property taxes next year to the city of Chicago and Chicago Public Schools.

CPS has proposed a $130.4 million property tax levy increase that will hit city taxpayers next year with an average increase of 4.2%.

Lightfoot acknowledges Chicago needs pension reform

Ultimately, it is impossible for Lightfoot or any other person to close Chicago’s long-term structural budget deficit without changing the Illinois Constitutional to allow pension reform that slows the growth in future benefit increases. Annual contributions for the four pension funds for which the city is responsible are scheduled to rise $135.4 million in the 2021 budget and consume 14.2% of the total city budget. By the end of Lightfoot’s first term as mayor, pensions will cost at least $1 billion more annually than they did in 2019 at the end of Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s term.

The effects of COVID-19 on pension investments could mean even larger increases than currently projected in the budget. Under a law that Emanuel pushed the General Assembly to pass in 2017, the city is currently making pension contributions for laborers and municipal employees in dollar amounts fixed by statute. Starting in 2022, those contributions will be actuarially determined, meaning investment losses will drive taxpayer costs higher. The mayor’s budget acknowledges the likelihood pensions will grow more quickly than previously anticipated in a foot note: “These projections may shift over time based on investment returns and other pension fund changes as the City gets closer to making those actuarial-determined contributions.”

Lightfoot deserves credit for speaking directly to state lawmakers in her speech when she said, “To our partners in Springfield… yes, we still need real pension reform.” However, Lightfoot did not define her idea of “real pension reform” and did not endorse a constitutional amendment, the only solution that can fix Illinois’ state and local pension crisis

Since taking office, Lightfoot has sent mixed messages on pension reform. While the mayor has made public statements recognizing the need for structural pension reform – including criticizing 3% compounded post-retirement annual raises as “unsustainable” – these statements have always been walked back by the mayor’s communications staff.

Emanuel had endorsed a constitutional amendment to allow structural pension reform but waited until he was on his way out the door. As a result, his endorsement likely carried much less weight with state lawmakers, who need to approve the reforms.

Chicago taxpayers have been hit with significant tax increases in recent years to the tune of $864 millionannually under Emanuel. More could be ahead depending on the outcome of a vote Nov. 3 on a constitutional amendment.

‘Fair tax’ passage would open the door to city income tax

If voters approve the progressive income tax amendment, called the “fair tax” by its supporters, they’ll be increasing the likelihood of a new city income tax to help close the remaining gap in Chicago finances.

Under the current constitution, home rule municipalities could implement flat local income taxes with approval from the General Assembly. But the requirement that local taxes apply to all taxpayers at the same rate acts as a barrier by making them politically more difficult to implement. Hitting all Chicago taxpayers at once would almost certainly generate more unified opposition.

Progressive tax powers make it easier to raise taxes on all income earners over time by granting lawmakers the ability to divide the population and charge different rates to different groups. The original constitutional amendment introduced in the Illinois Senate stated, “No government other than the State may impose a tax on or measured by income.” But this was changed before the amendment was sent to voters. It now would allow for city income taxes or being taxed multiple times on the same $1 earned. If voters approve the amendment Nov. 3, they could be adding city income tax hikes to the list of tax increases facing Chicagoans, along with property and gas tax hikes.

If they instead reject the amendment and preserve the flat tax protection the constitution’s authors fought to include 50 years ago, they can send a message that lawmakers need to stop asking taxpayers to pay more when they’re struggling the most. Voting “no” on the “fair tax” would preserve the flat tax and prompt Springfield to make the structural changes needed to close Chicago’s and Illinois’ chronic deficits in a way that respects taxpayers.